- Radheshyam Bishnoi, wildlife protector, has died at the age of 28.

- Radheshyam began by helping injured animals in the desert, learning the delicate art of handling wildlife, especially the great Indian bustard, a critically endangered species.

- His early conservation efforts laid the groundwork for a lifetime of impactful work.

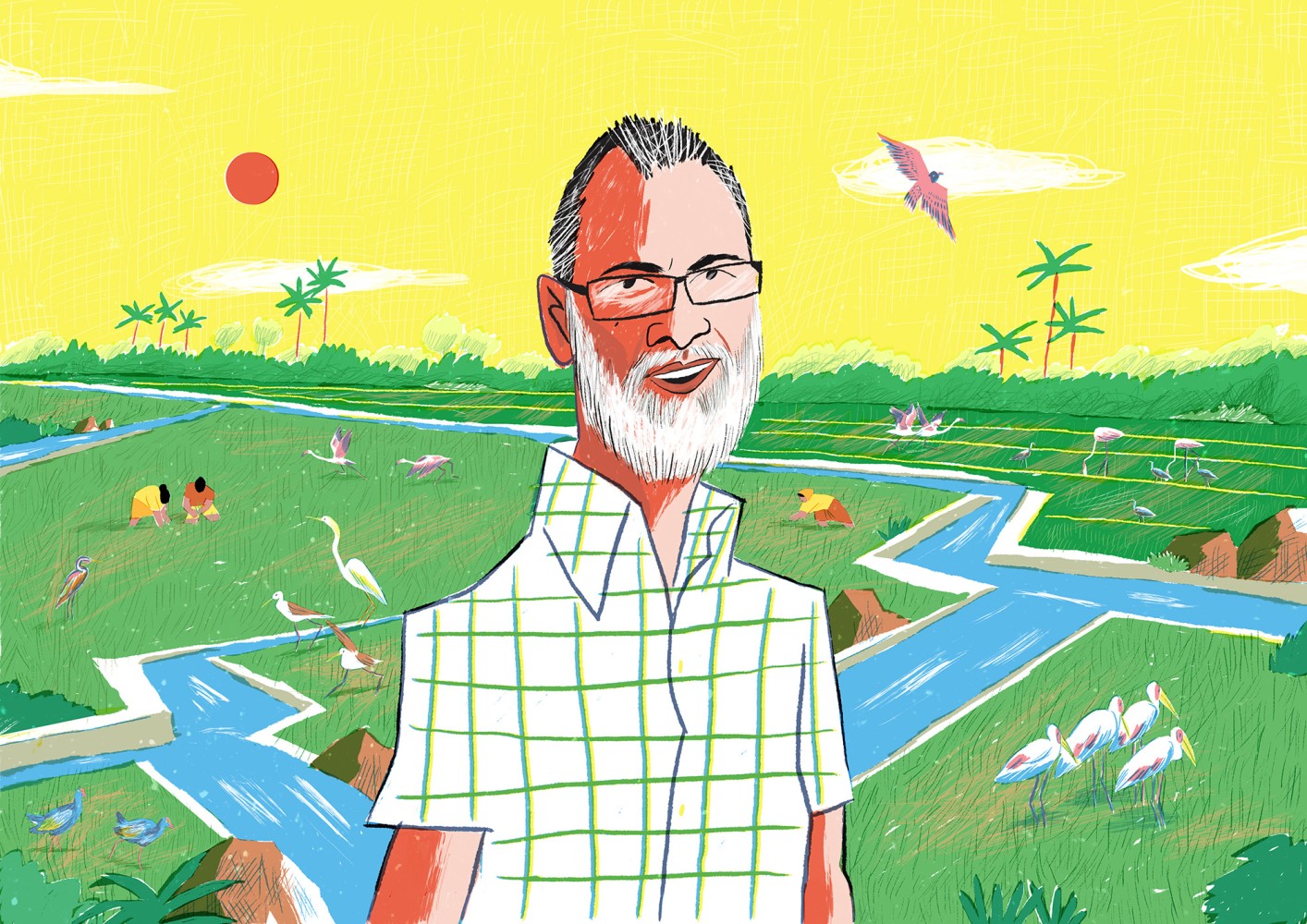

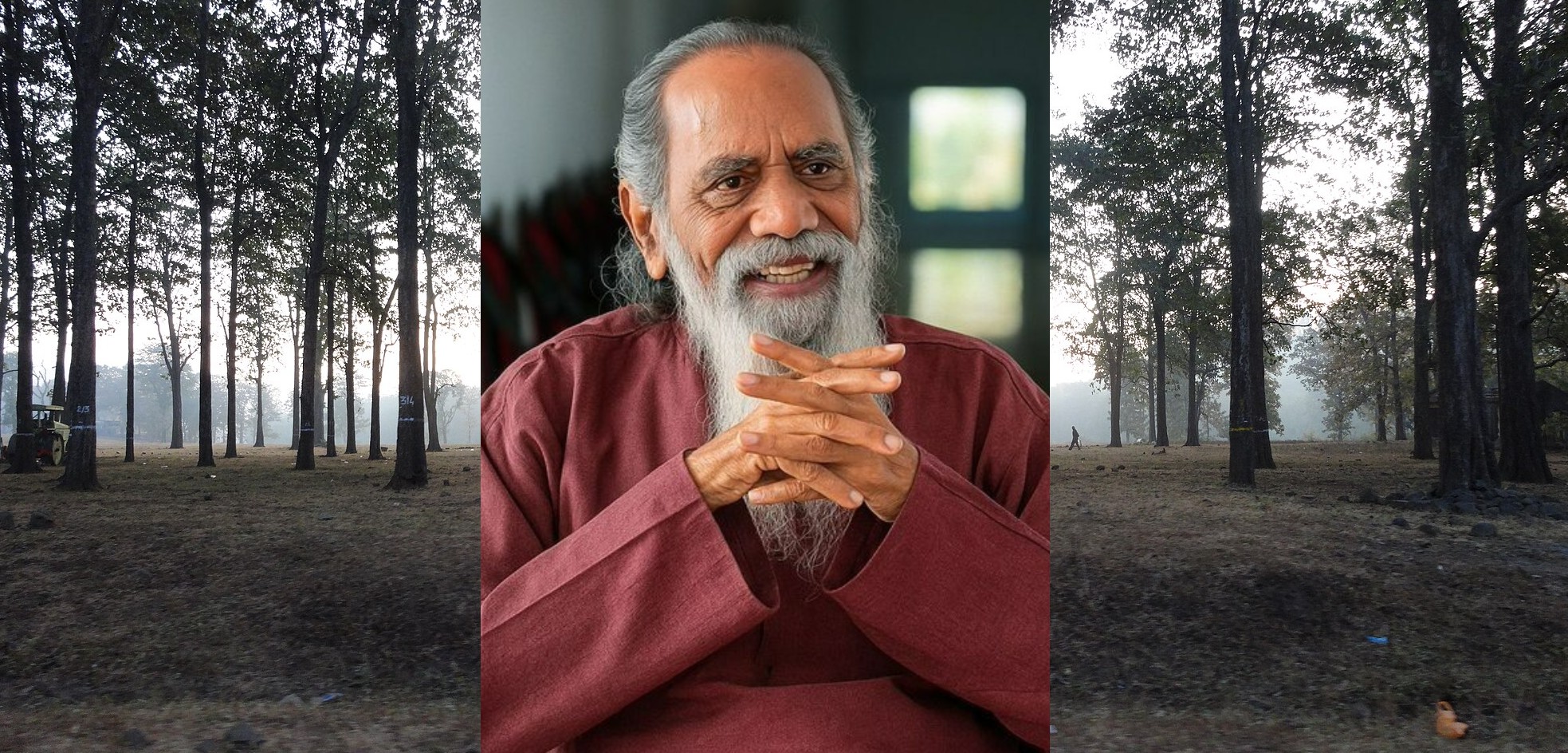

To anyone interested in wildlife conservation in the Thar landscape, Radheshyam Pemani Bishnoi is a name that is quite familiar. A young, 28-year-old man from Dholia village in Pokhran, Rajasthan, his passion towards conserving the critically endangered great Indian bustard, rescuing injured birds and animals, and helping forest department officials thwart attempts of poaching, earned him accolades and respect across different quarters.

On the night of May 23 this year, Radheshyam lost his life tragically along with three others in a car accident late at night. Along with Radheshyam, Forest Guard Surender Chaudhary, Shyamlal Bishnoi, and Kanwaraj Singh also lost their lives in the accident. They were on their way to foil a deer poaching attempt.

For those in the wildlife conservation community, the locals and of course, his family, this loss is irreparable.

“I don’t know what to say…this loss is personal,” said wildlife biologist Sumit Dookia, with whose NGO, ERDS (Ecology, Rural Development and Sustainability) Foundation, Radheshyam had been actively involved in for the past many years. Dookia recalled meeting Radheshyam back in 2016 during a training session of local youth living in villages near the Desert National Park (DNP) to work as nature guides. Radheshyam was not among those who attended this training but expressed interest in being a part of the conservation efforts. Thus, began his journey in conserving the great Indian bustard (GIB) and its habitat. Over the years, he became instrumental in protecting GIB habitats, rescuing injured birds, monitoring threats like high-tension power lines and windmills, and advocating its conservation among locals.

During a conversation with me a few years ago, Radheshyam mentioned how he once compensated a farmer in whose field a GIB had laid eggs. “It was a sewan (grass, for fodder) field and after I spoke to him at length, the farmer agreed not to disturb the eggs,” he had told me. Over time, he built a strong network among the local community such that whenever there would be a sighting of a GIB, or its death, Radheshyam would immediately be informed. “Once a GIB was stuck on a fence in a field…the villagers informed me and I could rescue it,” he had shared.

Radheshyam’s love for wildlife took root as a child when he would often bring home injured birds to treat them. That he belonged to the Bishnoi community which reveres wildlife and the environment also played a role in moulding his young mind.

Dr. Shravan Singh, who works at the Vulture Conservation Breeding Centre in Haryana, was particularly distraught when he heard of Radheshyam’s untimely demise. Radheshyam had learnt the basics of first-aid for animals from him when he was the veterinarian in Jodhpur’s Machia Biological Park Rescue and Rehabilitation Centre. “Radheshyam would often bring injured chinkaras, birds, blue bulls, to me on his truck from Pokhran almost 170 kms away, because they did not have such a facility there. In the monsoons, the incidence of chinkaras being attacked by stray dogs would increase. So, Radheshyam asked me if he could learn the basics of first-aid so that he could treat some of the animals there,” Singh told Mongabay India. The young conservationist worked as an apprentice with Singh for two weeks and later used that knowledge to give immediate treatment to injured animals.

Govind Sagar Bharadwaj, now the member secretary of NTCA (National Tiger Conservation Authority), went on to add that Radheshyam’s loss would also be felt by the forest department. Bharadwaj was the Chief Conservator of Forests (Wildlife Division), Jodhpur, when ERDS had conducted the training of local youth along with the forest department. “Many youth were trained at that time, but he was perhaps the only one who developed such passion for landscape and wildlife conservation. His contribution has been immense and so this loss, is big,” Bharadwaj told Mongabay India. Radheshyam played an important role in anti-poaching efforts, leading to the arrest and registration of FIRs against those involved in such activities.

Dookia also added how, over the last few years, Radheshyam led the effort of creating 12 water points for animals in the harsh summer months around DNP. “Every alternate day, he would take his truck to these points and fill them with fresh water sourced from his tube well,” Dookia said, “Even when the India-Pakistan border tension escalated, he continued to go to these far-flung water points and refill them.” This project, although adopted through crowdfunding, involved many additional expenses that Radheshyam bore without hesitation.

For his work, Radheshyam was awarded the Sanctuary Nature Foundation’s Sanctuary Wildlife Service Award in 2021 under the Young Naturalist Category. Calling him one of the ‘strongest defenders of wildlife in Thar’, Sutirtha Dutta, senior scientist at the Wildlife Institute of India (WII) said that his conservation footprint, despite his young age, would be hard to compare.

“Radheshyam became a crucial part of our fight to save the GIB habitat outside the DNP — we had to fight tooth and nail against corporate nexus to bureaucratic procedures. We started working from scratch and had finally reached a point where our voices were beginning to be heard,” Dookia said. “Radheshyam was unlike many others; he did not do things for personal gain. It will be difficult to fill this void that he has left.”

It is a sentiment echoed across the chamber of wildlife enthusiasts, photographers and writers like me, who were always helped by this young conservationist in all ways possible.

Radheshyam is survived by his wife, two young children, parents and other members of his family.

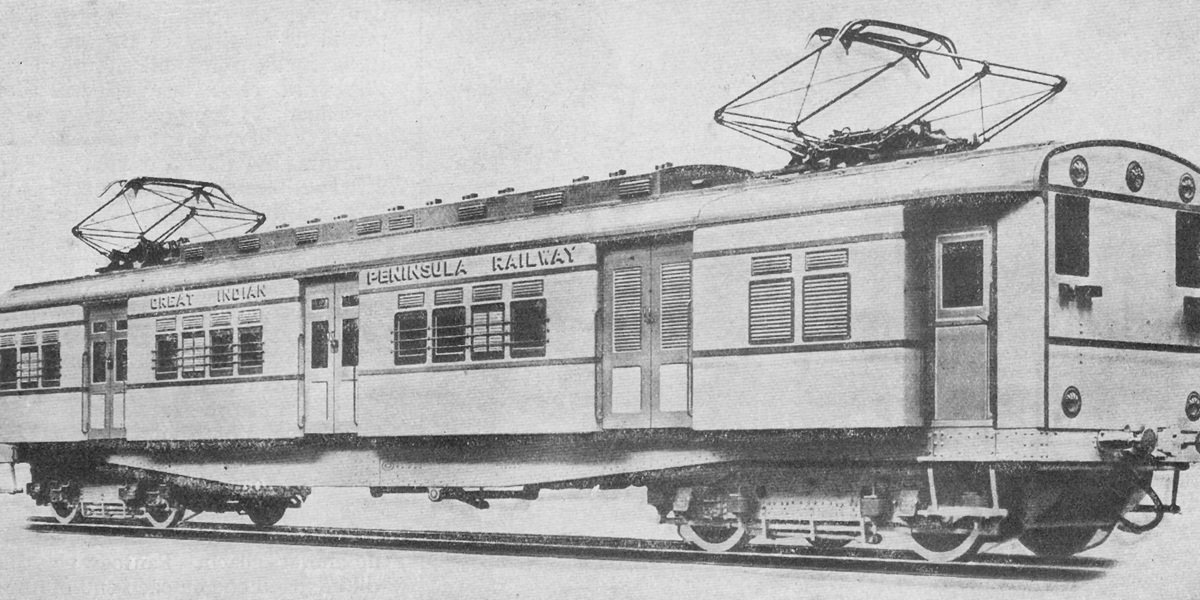

Banner image: Radheshyam Bishnoi examines a spiny-tailed lizard burrow in Pokhran, Rajasthan. The burrow has been dug out by poachers. Image by Sneha Richhariya.