The narrow lane outside Navarang Theatre in Vijayawada’s Governorpet was once abuzz with taxis and autorickshaws that brought an excited audience. On billboards, large posters caught the movie cast in the thick of action and drama, and in the air, hung faint snippets of dialogues and music wafting out from the hall.

Opened in 1964, Navarang Theatre was a cultural landmark, where rickshaw pullers and taxi drivers took pride in watching Hindi and English movies alongside the city’s elite. Blockbusters ran for months, with word of mouth doing its magic. Today, however, silence has shrouded the theatre, its empty seats and faded walls a stark contrast to the housefulls in its heyday.

Navarang Theatre is one of the last few independently run single screens in Andhra Pradesh. Most of its contemporaries, including the State’s first theatre Maruthi Talkies, Vijaya Talkies, Sri Durga Mahal, Mohan Das, all in Vijayawada, have shuttered, while many others have either leased out their theatres or rented them out as real estate properties.

The decline began decades ago, when televisions became commonplace in households. Then came the internet revolution, the smartphone penetration and, finally, the proliferation of OTTs. These, along with an “unreasonable” revenue-sharing model between distributors and exhibitors seem to have finally broken the back of this once-prosperous industry.

Rolling with the punches

For Navarang Theatre proprietor R.V. Bhupal Prasad, its “passion” that keeps him in the business. His family used to own 13 theatres, including Saraswati Talkies, Saraswati Picture Palace, Leela Mahal and Navarang, across the State. Leela Mahal, which opened in Vijayawada in 1944, was the first theatre in the Andhra region of the Madras Presidency to screen English and Hindi movies.

An old projector on display at a theatre in Vijayawada.

| Photo Credit:

G.N. RAO

Today, he agonises over which movie to screen. “It is exhausting; we don’t know which movie will strike a chord with the audience. Sometimes, even a big-starrer tanks at the box office, and sometimes, a small movie makes waves,” he says.

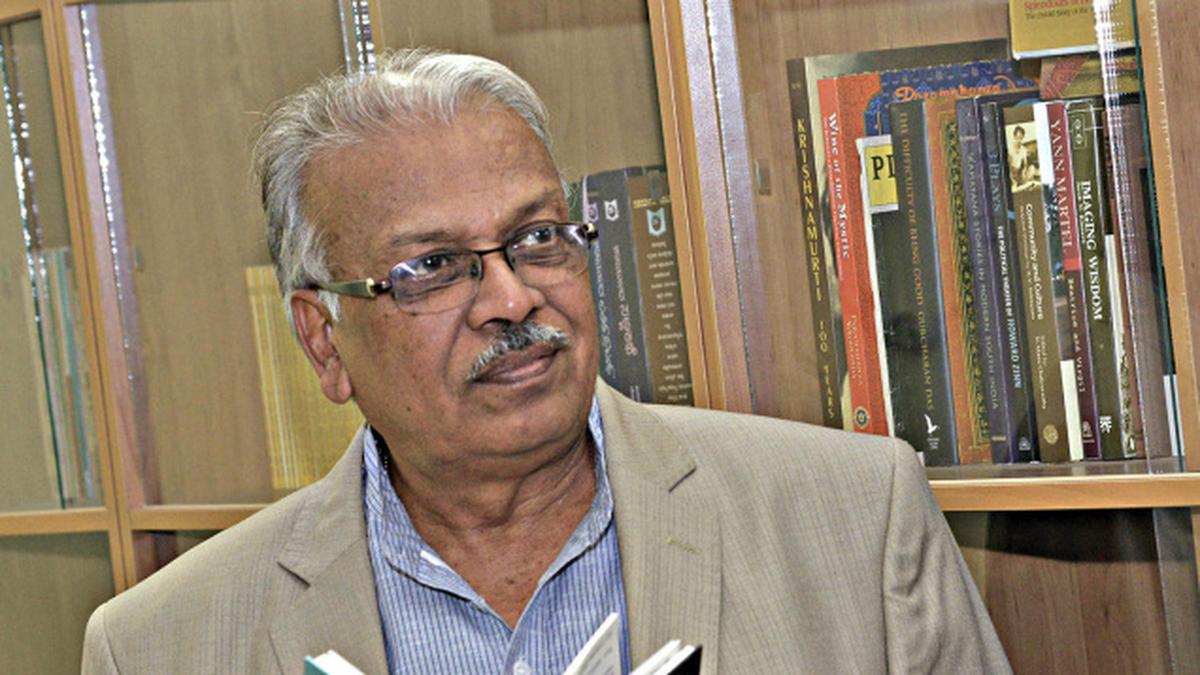

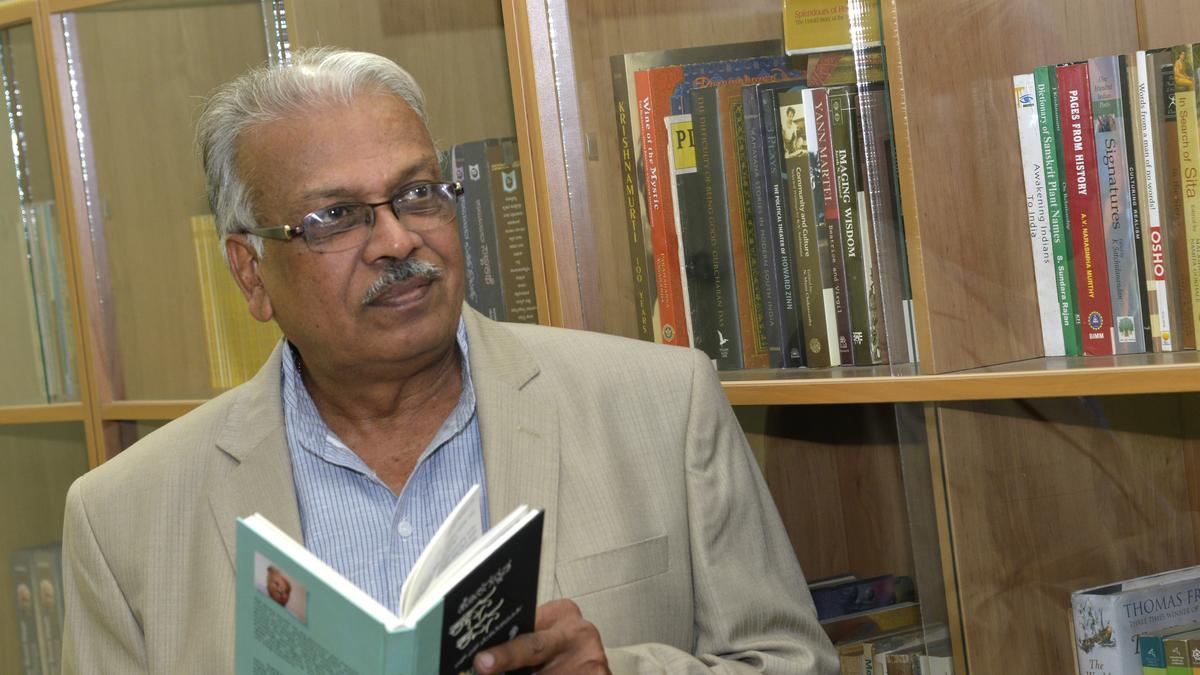

In a 2021 research paper titled Amplification as Pandemic Effect: Single Screens in the Telugu Country, authors S.V. Srinivas, a professor of literature and media studies at Azim Premji University, Bengaluru, and Raghav Nanduri say that around 90% of single-screen theatre owners in Andhra Pradesh have leased out their theatres.

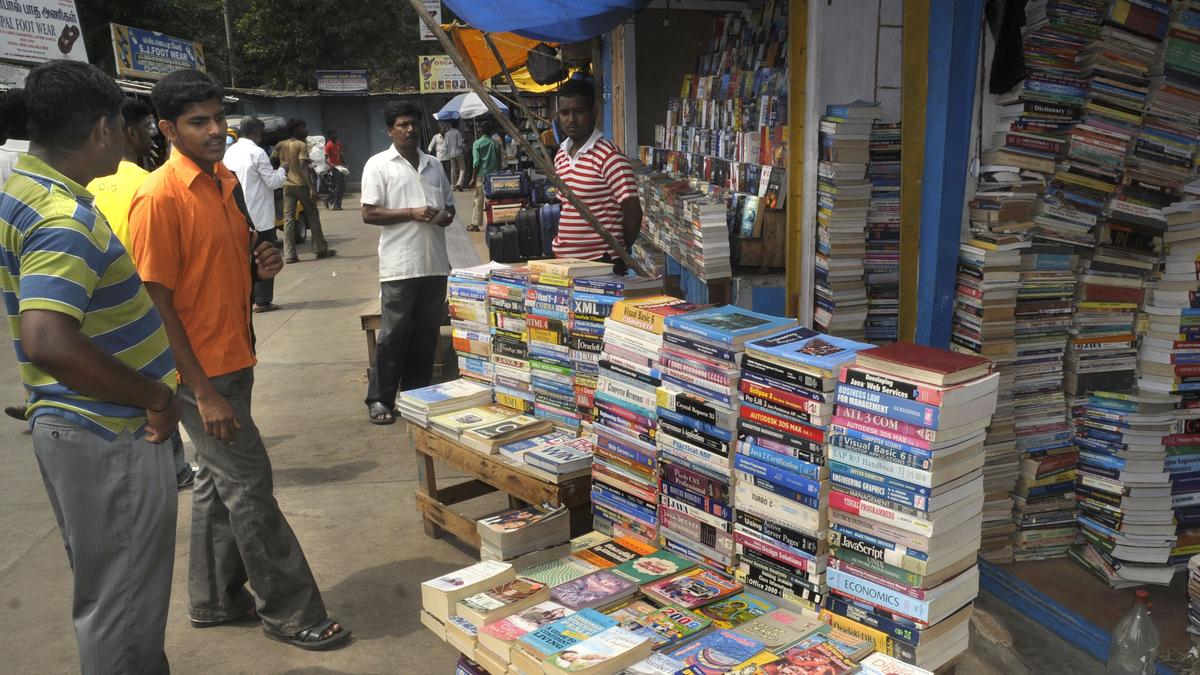

Dwindling business is one reason why they did it. “These days, pirated copies reach one’s smartphone even before the film’s release. Why would anyone want to incur losses? So, they lease the theatre out to those who have the wherewithal to run it. That guarantees a stable income. These days, running a supermarket makes more sense,” says a veteran exhibitor, who sought anonymity. Across A.P. and Telangana, over 600 independently run single screens are haemorrhaging money.

Srinivas, one of the authors of the research paper, says that leasing has helped single screens survive. “Under the lease system, where most lessees are bigshots in the industry, many single screens were renovated and received a multiplex feel. Moreover, re-releases, too, have become the lifeline for many theatres.” However, some in the business feel that small producers find it difficult to get their films released in theatres run by these bigwigs.

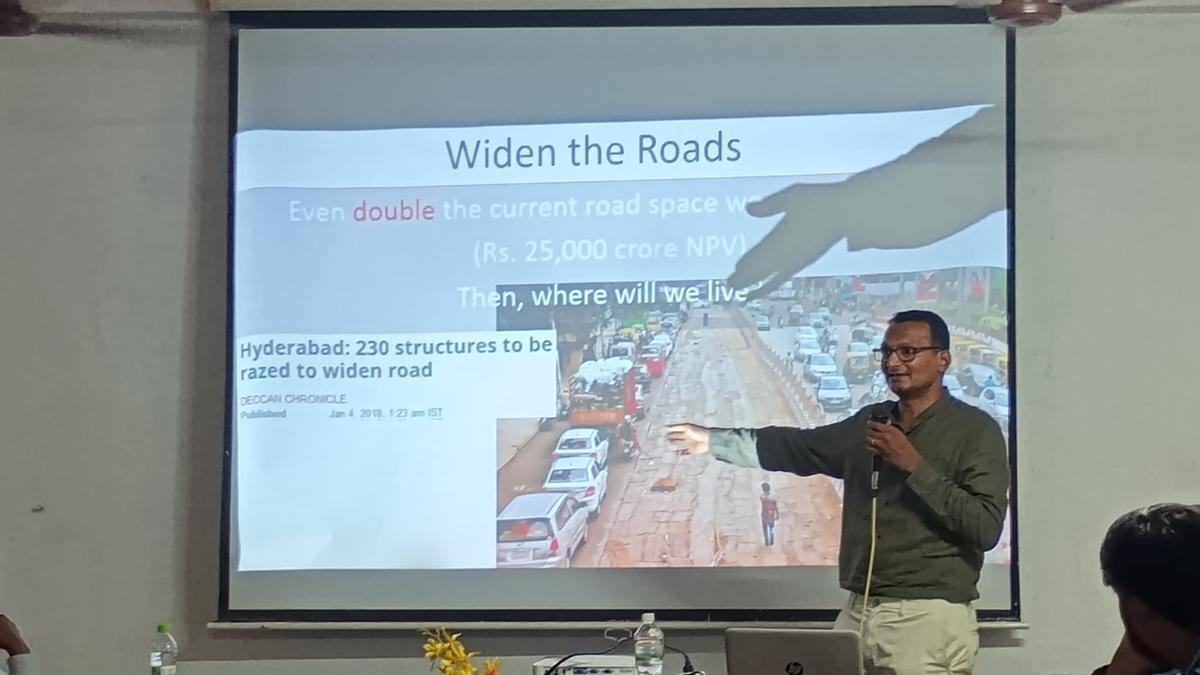

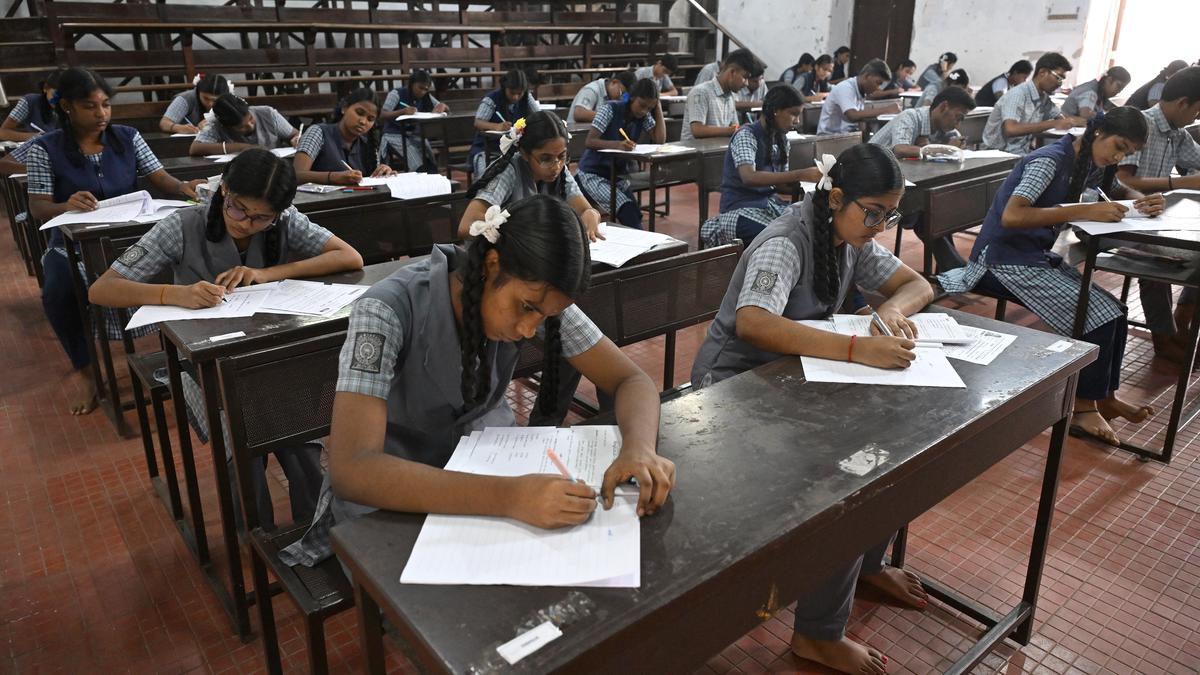

To be in the race with multiplexes, Sailaja Theatre in Vijayawada was renovated to offer more amenities to the audience.

| Photo Credit:

G.N. RAO

On expenses, the veteran exhibitor explains that around ₹20,000 a day is needed to run a single screen in a city such as Hyderabad or Visakhapatnam. In smaller cities, it could be around ₹15,000. The power bill comes around ₹2.5 lakh a month and staff salary around ₹1.5 lakh. “If we get ₹4 lakh a month, we can break even, but we rarely get it.”

While Kamal Haasan’s 2022 movie Vikram fetched him ₹7 lakh in the first week, the same actor’s recent movie Thug Life barely scrapped together ₹7,000, opening to a 6% occupancy rate in his theatre. “I incurred a loss of ₹3 lakh over the past four months,” he adds.

Revenue sharing model

While decreasing footfalls, piracy and OTT platforms are problems faced by multiplexes, too, their situation is slightly better, say some single-screen owners. And it is here, in the difference, that the chief concern of exhibitors comes to the fore: the revenue-sharing model.

To understand the revenue-sharing model between the exhibitors and distributors, it is important to know how the system of buying-distributing-selling of a film works.

“The concept of exhibitor-distributor existed since the first movie,” says Grandhi Viswanath, who has nine single-screen theatres across the State. His grandfather, G.K. Mangaraju, became the first distributor and exhibitor in the State in 1927, when silent movies gave way to talkies. His distribution office, Poorna Pictures, is the first distribution company in the State.

“Earlier, it was a healthy system. A producer would inform the distributor about a new movie. A distributor would look at the casting, content and production cost and then invest in the movie to buy the rights. There used to be one distributor for an entire region for that particular film. The distributor would have links with a few theatre exhibitors, to whom the print of a film would be handed over. The ticketed revenue was shared on a percentage basis between a distributor and an exhibitor,” he explains.

Because only one or two theatres screened a film, it would have a good run. The A. Nageswara Rao-starrer Devadasu ran for 140 days in Vijayawada’s Maruthi Theatre, the State’s first theatre opened in 1921.

Now, however, old established distribution companies have been replaced by ‘buyers’. Mr. Srinivas and Nanduri, in their research paper, say: “These buyers could be anyone with the capital to bid for distribution rights. Typically, buyers would bid competitively, and speculatively, for rights in a single-distribution territory, resulting in substantial gains for producers of big-budget star vehicles.”

According to some film exhibitors, the entry of these buyers heralded the downfall of their industry. Mohan (name changed), an exhibitor, says there is a distributor for every district now, and that person ensures that the film is released on all the screens across that district.

“These days every new movie is screened simultaneously on all the screens. When the audience is spread among so many theatres, the chances of a theatre seeing a housefull dwindles; the audience thins out on the second day itself,” he adds.

Moreover, these days, the new-age distributors help producers finance big-budgeted films. The distributors collect half the amount the producer requested from theatre owners. If the film fares well, the producers give back the advance amount to distributors, who, in turn, give it back to exhibitors. If the movie is a flop, then exhibitors do not get their money immediately, according to some exhibitors. This has resulted in exhibitors’ money getting blocked for a long time. Depending on the locality and the film’s potential, the advance may range anywhere from ₹5 lakh to ₹40 lakh.

This, in addition to the current revenue-sharing model, has crippled single-screen theatres in the State. “The distributors decide on the revenue sharing unilaterally. In the first week of the theatrical release of a movie, the distributors either give us a rent or a percentage system, whichever gives them more profit. If the movie is a hit, the distributors give us a rent. If it’s a flop, they offer a percentage,” says Mohan.

The way forward

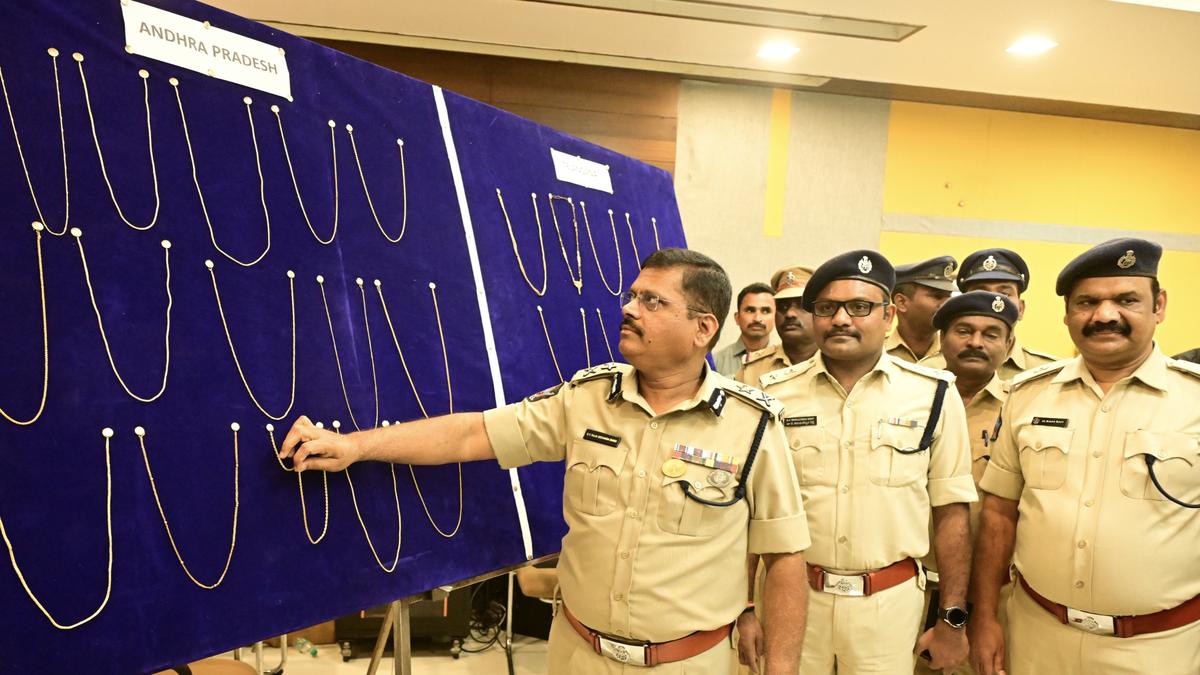

In May, film exhibitors in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana announced that they were not in a position to continue to screen movies. Mohan says that one of their chief demands is that the ticketed revenue be shared on a percentage basis, like how it is in multiplexes and other States. “The percentage model can solve some of our problems,” he feels.

According to the research paper, single-screen theatres continue to be important for box office collections and contribute up to 60% of ticketed revenue. Despite this stature, no new single-screen theatre has come up in the two Telugu States over the past decade, says the veteran exhibitor.

Mr. Grandhi Viswanath feels that along with the overhaul in the revenue sharing system, the government should allow flexible admission rates (ticket prices) as well. Currently, ticket prices in the State are fixed in accordance to the Government Order (G.O. Ms.No.13) issued on March 7, 2022. In this order, the government had fixed rates for different type of theatres in municipalities and corporations.

“The exhibitors should be given the discretion to decide on the admission rate (ticket price) of a movie, depending on its potential. This will help get more patronage for smaller movies,” he says.

Echoing this, Chandrasekhar (name changed), another exhibitor, points out that the exorbitant production costs of a film leads to higher ticket prices. Once a moviegoer spends ₹250 a ticket for a big-budget movie, they may not see another film in a theatre for, say, a month. “Smaller movies, released after the big-budget movies, often get killed thus. The theatres, too, hence do not see much footfall,” he says, adding that the government should also ensure that a movie is released on the OTT platform eight weeks after the theatrical release.

Chandrasekhar says that theatre owners like him never called for a bandh. “It is unfortunate that we were misinterpreted; we only want to request the government to consider our demands for a percentage system, which will allow us some breathing space. After all, our goals are the same, to bring back audience to the theatres.”

What distributors say

A distributor in Visakhapatnam, who sought anonymity, says it’s the distributor who stands to lose more than an exhibitor when a movie flops. “The success rate these days is 6%. We invest in a movie and we lose when it flops. The exhibitors do not have anything to lose. They can at least benefit from parking charges. The advance amounts that they have to part with are immediately returned.” To the exhibitors’ demand for implementation of a percentage system (for all the weeks), he said this would be disadvantageous for distributors.

Responding to the exhibitors’ concerns, Telugu Film Chambers of Commerce president Bharath Bhushan says distributors, too, are facing problems. The whole issue stems from a dearth of hits in the industry. “A flop movie is a death knell for everyone”

The Telugu Film Chamber of Commerce has formed a committee of 30 members, comprising distributors, exhibitors and producers, to work out a solution amenable for all. The report is expected soon. Bharath Bhushan says a decision regarding the demands would be taken after a meeting with the stakeholders on June 23 and 24.

After A.P. Deputy Chief Minister K. Pawan Kalyan emphasised the need for regulating cinema halls properly across the State and keeping food, beverages prices reasonable, many are hoping for a positive outcome from these meetings.

Published – June 13, 2025 09:43 am IST