- Mizoram has witnessed a rise in forest fires in recent years, primarily triggered by slash-and-burn for jhum cultivation.

- The profitability of ginger farming and the state’s promotion of it, have led to a surge in shifting cultivation.

- Traditional community-based fire management practices in Mizoram, once a strong line of defense, are gradually fading due to declining participation.

In March this year, a fire raged through Mizoram’s Phawngpui National Park, one of the state’s most critical biodiversity hotspots, for 17 consecutive days. According to the Forest Survey of India (FSI), the blaze erupted at 19 different locations within the park, charring nearly one-ninth of its 50 square kilometre-area. Among the most affected zones were the northern slope of Mount Phawngpui, Mizoram’s highest peak, and the ecologically significant Far Pak grasslands.

The fire was traced back to slash-and-burn activities at a jhum cultivation site near Archhuang, a village located close to the Park’s boundary. According to the Deputy Conservator of Forests for the Chhimtuipui Wildlife Division (Lawngtlai), R. Lalruatfela, at the time of the incident, the forest floor had developed a thick layer of humus due to the absence of any controlled burning or natural fires over the past five to six years. “This build-up fuelled the fire. Fortunately, there were no wildlife casualties and natural regeneration is picking up in the affected areas,” he informs Mongabay India.

Creating fire lines is crucial and remains the only method known to effectively prevent fires from spreading from jhum fields into forest areas, according to Lalruatfela. “In this case, the Archhuang Village Council failed to create firebreaks and implement the mandatory preventive measures before igniting the fields. It has been penalised ₹1 lakh under the Wildlife (Protection) Act,” he points out.

According to the Mizoram Forest Department, FSI reports show a marked increase in fire alerts during the November-to-June fire season, based on satellite data from the SNPP-VIIRS (Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership-Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite) sensor. Alerts rose from 7,361 in 2019-20 to 12,846 in 2020-21. In 2023-24, 6,627 alerts were recorded, primarily linked to shifting cultivation. Media reports, citing the state’s Environment, Forest and Climate Change Department (EF&CC), indicate that in 2024 alone, slash-and-burn practices caused 3,496 fire incidents, affecting over 38 sq. km.

The general secretary of the Central Young Mizo Association (CYMA), Malsawnliana attributed most fires to negligence. He notes that all 821 Young Mizo Association branches are working to raise awareness and assist during such incidents, despite receiving no financial support from the government.

Policies reshaping jhum

Despite a gradual decline in jhum practices over the years, the profitability of ginger farming and its promotion by government agencies have led to a renewed interest in traditional shifting cultivation. “In the absence of proper guidance on sustainable practices, most farmers are reverting to shifting cultivation, which is contributing to an increase in fire incidents,” says Lalbiakmawia Ngente, president of the Mizoram Environmental NGOs Coordination Committee (MENCO).

Called Lo neih in Mizo, shifting or jhum cultivation has long been a way of life in Mizoram, where over 70% of the state’s 21,081 sq. km. geographical area lies on slopes of 35% or more. The former Congress government implemented the New Land Use Policy (NLUP) in three phases — 1984-87, 1991-97, and 2011-14 — aimed at providing jhumias (traditional jhum practitioners) with sustainable livelihood alternatives and enhancing forest cover by curbing land-clearing practices.

As a result, the area under shifting cultivation declined from 681.14 sq km in 1997-98 to 146.84 sq km in 2023-24. The Economic Survey 2024–25 attributes the decline in jhum between 2005-06 and 2023-24, in part, to the adoption of oil palm cultivation in the state.

Some attribute the rise in both the frequency and intensity of forest fires in Mizoram to the unregulated selection of jhum sites — an unintended fallout of the government’s push for cash crops under the Socio-Economic Development Policy (SEDP), and the erosion of traditional community-led fire management.

In 2019, the Mizo National Front government replaced the NLUP with the SEDP, a broad, long-term initiative aimed at transforming Mizoram’s economy through self-reliance, sustainable livelihoods, and inclusive growth. Unlike NLUP, which focused on phasing out jhum by promoting settled farming, the SEDP prioritised overall socio-economic upliftment, including entrepreneurship, skill development, and rural infrastructure. While it supported settled farming, it did not explicitly aim to reduce jhum.

Under SEDP, the government announced minimum support prices for the GI-tagged Mizo ginger, turmeric, Mizo chilli, and Asian broom grass. With additional market support from the Mizoram Agricultural Marketing Board, the area under ginger cultivation increased from 85.5 sq km in 2019-20 to 87.13 sq km in 2023-24.

“Ginger has long been grown in Mizoram, but since 2023, more farmers have begun cultivating it on a larger scale and earning well. For any cultivation, landless households are allotted at least one hectare by the village council, free of cost. Those with land can clear as much as they need,” says Champhai district farmer John Lalrinchhana Jahau.

“In recent years, rapid population growth has led to land scarcity and fragmentation, reducing fallow periods from 10 years to under five. This overuse has lowered soil productivity, prompting more forest clearance and raising the risk of fires spreading,” notes Ngente.

Although there is a penalty of ₹500 to ₹1,000 for fire incidents, the enforcement is weak. During the jhum season, multiple fires are lit in nearby fields, making it difficult to trace the source. This lack of accountability has hindered stricter penalties, despite rising fire risks.

Shifting fire governance

Traditionally, village elders identify and allot plots to jhumias, with land cleared and burned between January and April. These dry, windy months often cause fires to spill into surrounding forests. The rugged terrain makes fire control especially challenging.

To manage the risks, Mizos follow community-based fire control systems led by Village Councils (VCs), relying on local participation and timely response, with both preventive and punitive measures. A fire line of eight to 10 metres is cleared between slashed vegetation and forests, and fire watchers are appointed during the season. Villagers use long knives (chem or dao) to cut branches and contain flames, spades to smother them with soil, and water-filled containers are kept ready at homes to douse sparks.

In 1983, the Mizoram government codified these traditions through the Mizoram (Prevention and Control of Fire in the Village Ram) Rules — among India’s earliest legal frameworks on forest fire management. “Village Ram” refers to land within a Village Council’s jurisdiction. Burning was permitted only during a defined, publicly announced period. Village residents had to seek prior permission and notify the Council at least three days in advance. Enforcement and prevention were made the responsibility of local communities, with collective labour (Hnatlang) and fire line clearing (Meilam) made mandatory. Violations incurred a fine of ₹50.

The rules were amended in 2001 and 2014. The 2014 revision increased institutional involvement, involving district and state-level monitoring, though village-level enforcement remained.

“Though government offices supervise and coordinate with village councils on forest fire prevention and control, the actual groundwork is carried out by the jhumias.

However, the number of participants is steadily declining due to alternate livelihood options and a lack of monetary incentives for the work,” says Vanlalhrima, MENCO’s general secretary, adding, “We’ve been urging the government to include fire line preparation under Category A of the MGNREGA (Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act), which covers public works related to natural resource management.”

Cheemala Siva Gopal Reddy, Deputy Commissioner of Lawngtlai, says, “In all my years in Mizoram, I’ve witnessed the highest number of jhum fires this year.” He adds that each district-level Fire Prevention Committee observes Fire Prevention Week in February, conducts awareness campaigns, and plans fireline creation and inter-agency coordination. In some areas, fire line labour is now included under MGNREGA, with additional support from CAMPA funds.

Read more: Wildfires and the forgotten science of community forest management [Commentary]

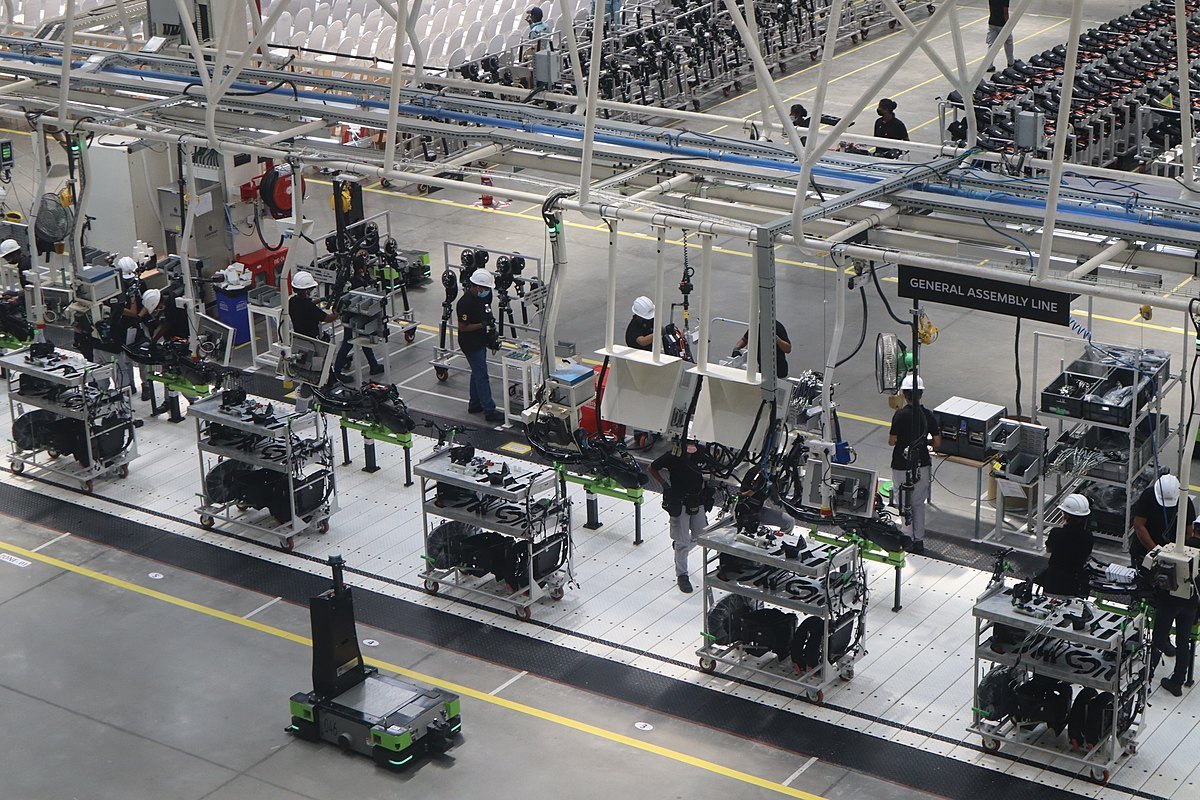

Banner image: Jhum cultivation in Khamlang, Ukhrul district, Manipur. Representative image by Viva Shanglai via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).