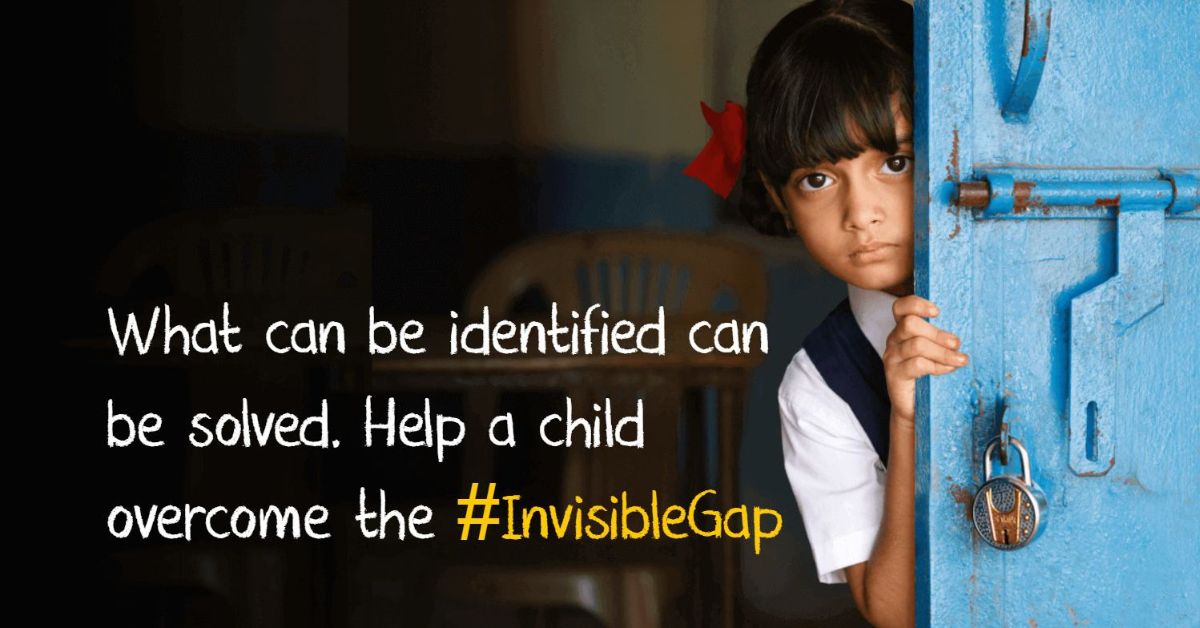

At the age of 10, were you able to comprehend simple English?

Well, 50 percent of children in India can’t.

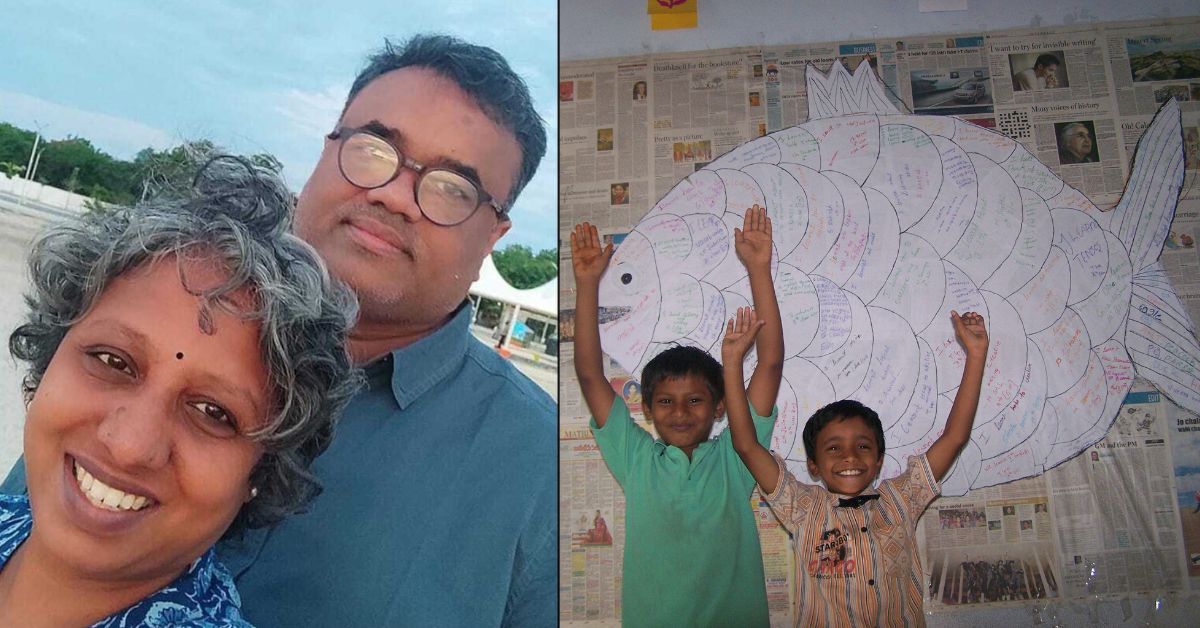

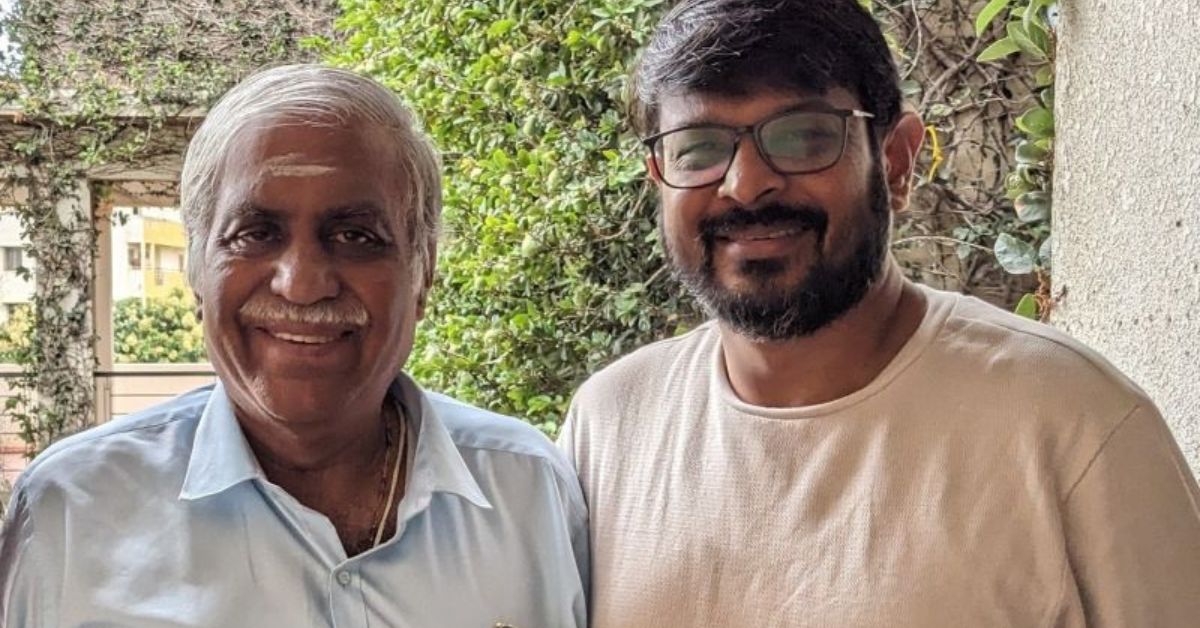

And, it’s futile to try to bandage the wounds of foundational literacy in adulthood, ex-IAS officer Dhir Jhingran (62) notes. What he suggests instead is that we tackle the systemic roots of the problem. His tenure as the district magistrate for two years in Assam’s Kokrajhar around 1986 forms the bedrock of his suggestion.

Advertisement

“There were many children who did not attend school there,” he recalls. To Jhingran, this felt wrong; something that even the absence of a ‘Right to Education’ Act — the Act was enacted in 2009 — couldn’t condone. “I just felt that every child should be in school,” he adds. Years later, he would recall this sentiment as the precursor of his Delhi-based Language and Learning Foundation, which, since its inception in 2015, has helped 14.2 lakh children directly and 1.62 crore children through indirect approaches (framing academic material).

Equitising education and creating a level playing field

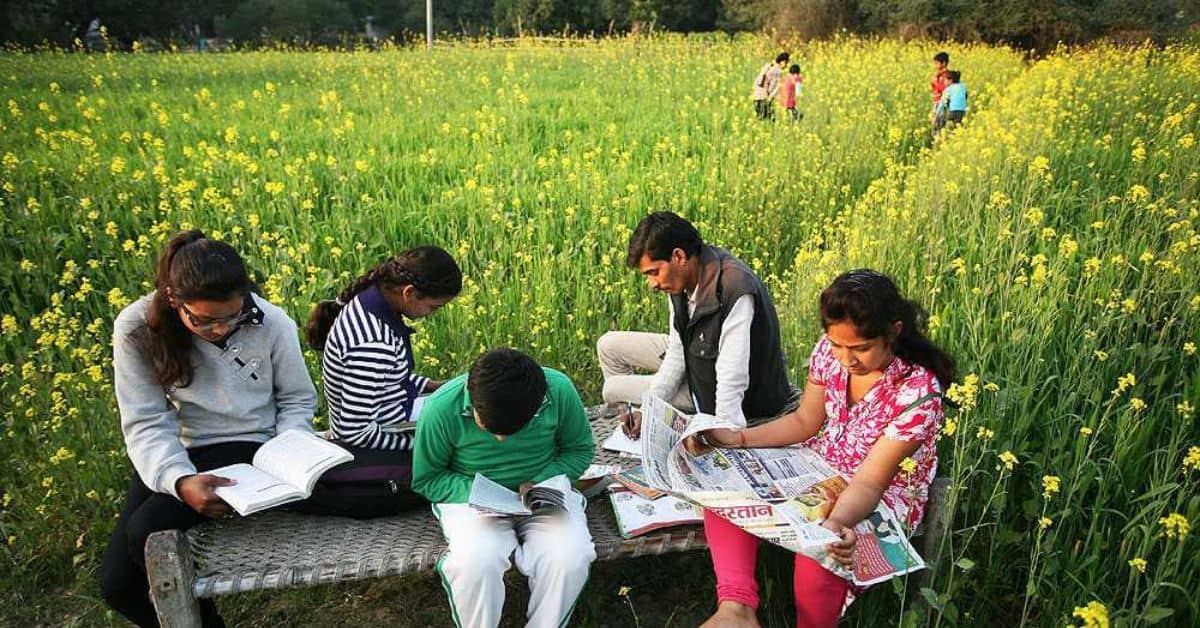

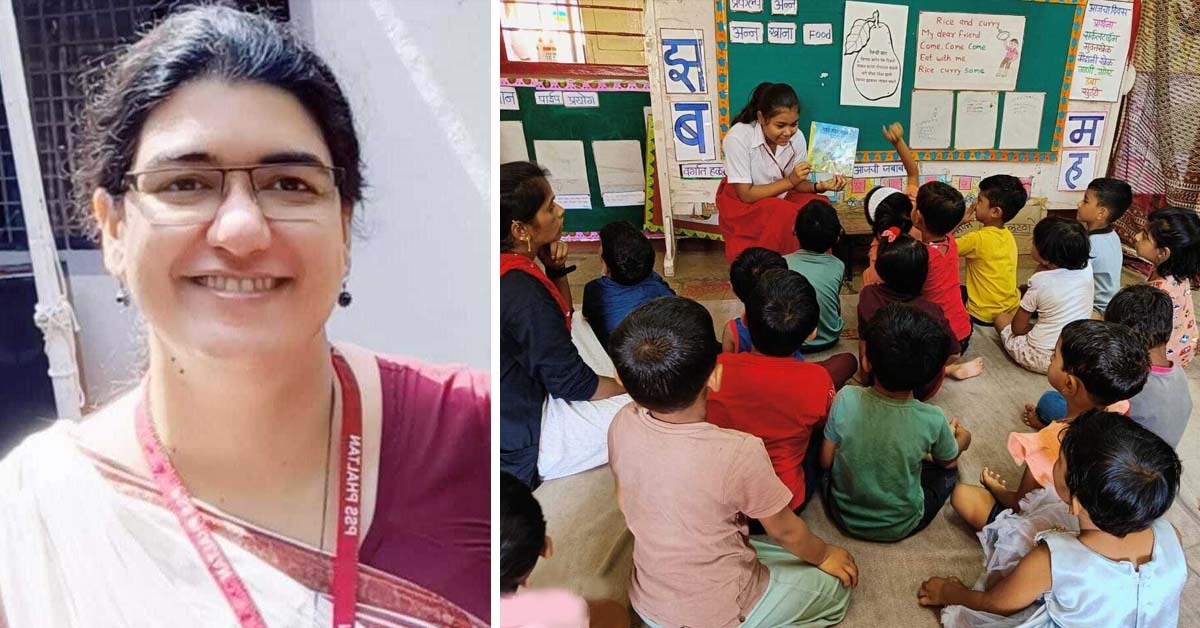

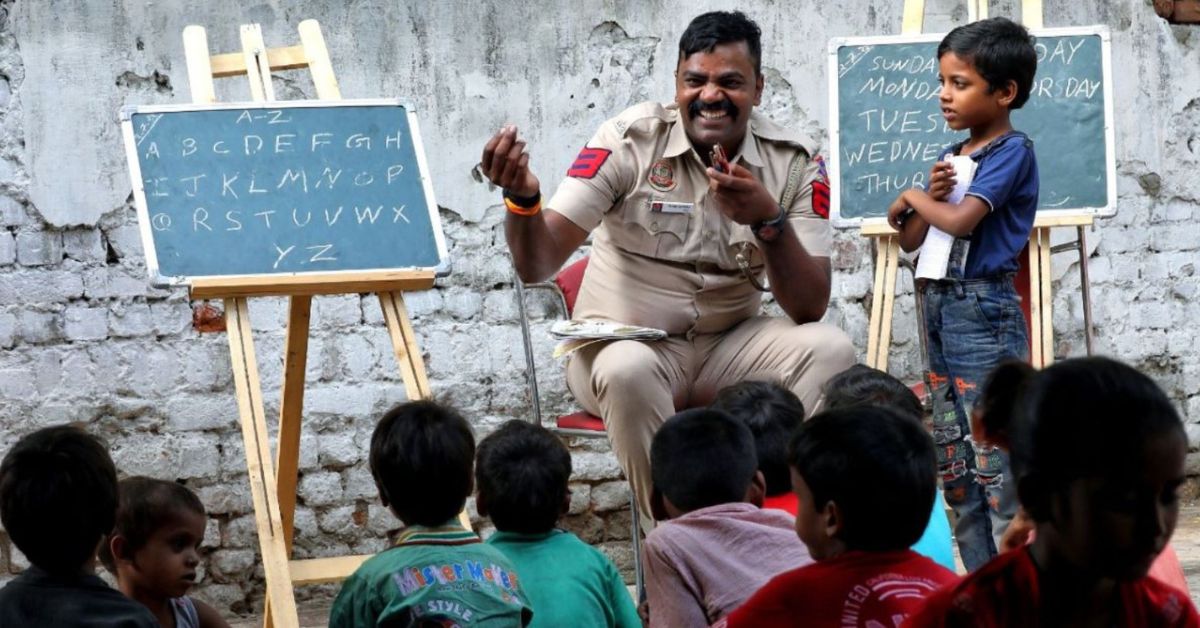

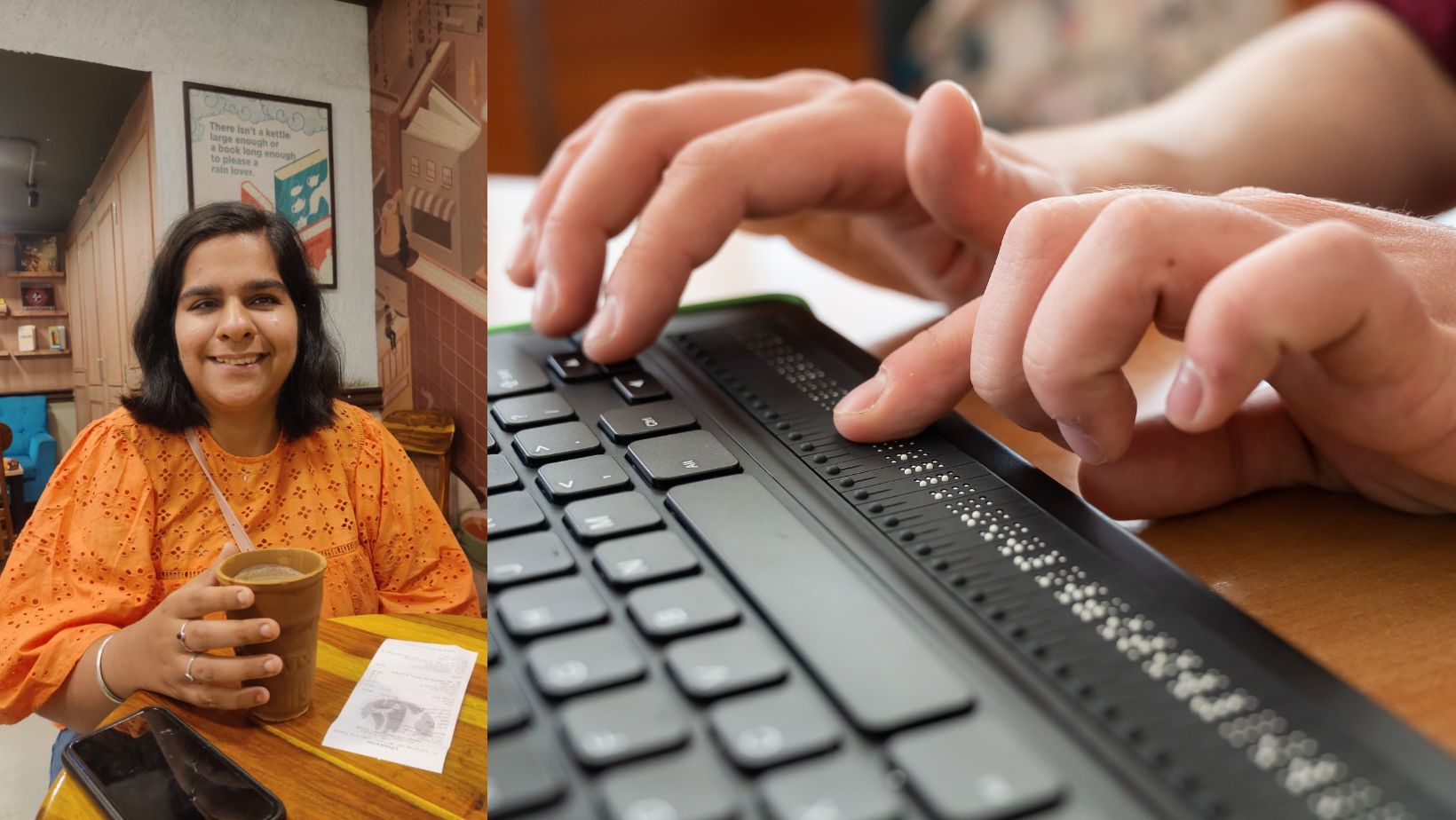

When the bell goes off for teacher Smita Chaturvedi’s lessons, her students are exuberant. They love her lectures. Smita is well aware of how crucial a sound foundation is for children’s academic milestones; she knows it can shape or break their futures. And so, she’s always attempted to breathe ingenuity into the topics she approaches.

But, for the better part of the 15 years that she’s taught at Koirajpur Primary School, in Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, all she had to rely on was the standard textbook. Aside from the prescribed definitions, it wasn’t of much use. It didn’t answer fundamental questions. For instance, how could she make a topic relatable? How could she make learning fun?

That Smita has managed to crack the code is because of her holy grail — the workbooks and handbooks provided to her by the Language and Learning Foundation. For the last three years, she’s been walking into class armed with dynamic strategies — a radical departure from the customary methods. Weaning the children off rote learning, instead deploying tactile aids, posters, cue cards, and colours, helps break the ice between the students and the world around them in a more fun way.

And is it working?

The spring in Smita’s step and the decibel of the children’s responses suggest it is.

Advertisement

“Earlier, we used to teach concepts in the usual ways. Our classrooms have changed since our school collaborated with the Language and Learning Foundation. Our walls are now filled with stories, and children want to learn. They feel enthusiastic,” she shares.

She adds, “The workbook does not just focus on questions but also on activities. I teach Hindi and math; in Hindi, we usually solve the vocabulary that is given in the textbooks. But with the workbooks, children learn how to identify the alphabet and how to use it in their daily language. The books give us different ways of teaching them poems and stories.”

Stories like these thrill Jhingran. It’s antithetical to the reality that he watched unfolding in the classrooms of Kokrajhar during his posting there. “I would find children sitting passively in classrooms. The teacher would be doing the speaking; I’m not sure the children were often even understanding what was happening.”

Further probing and conversations with the students revealed there was a language barrier.

“The children were used to speaking one language at home and were being taught in a different language in school. There seemed to be a problem,” Jhingran adds that the paucity of educational facilities, compounded by the fact that most children only spoke the tribal dialect, was slow-rippling into illiteracy.

When he extrapolated this to other tribal belts and remote areas of India, he found the situation there too mirrored Kokrajhar’s reality. There was a fast widening educational chasm.

Advertisement

Jhingran devised a three-step approach to tackle the problem. At the Language and Learning Foundation, these pathways, as Jhingran calls them, converge in raising a generation of students who can read, write, and think.

Sharing more about the three approaches, he says the first is a continuous string of in-person workshops, online courses, and cluster meetings that bolster teachers’ confidence; then follows collaborations with government agencies to help mainstream best practices — MoUs have been signed with state governments of Assam, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Haryana, Odisha, Rajasthan, and Uttar Pradesh. Thirdly, teachers are equipped with workbooks, guides, handbooks, and targeted daily lesson plans.

His career is chequered. Jhingran has spent a decade working with the government of Assam to improve literacy programmes; worked with the Ministry of Human Resource Development, during which he supervised and coordinated the District Primary Education Program (DPEP) in eight states; led the Government of India-United Nations’ Joint Program for Primary Education in eight Indian states; was National Education Advisor to the Ministry of Education, Government of Nepal and was senior advisor (education), UNICEF, India.

While the lack of foundational literacy among children is crucial, he realised it’s one vein in the growing ebb of the literacy crisis.

What about adult literacy?

Assam’s Kokrajhar was once notorious for ethnic clashes. This was around the same time that Jhingran was posted there. “It was a disturbed district. I was posted there to control the violence. While law and order was, of course, the priority, I came across a literacy campaign which had been approved by the government of India and the state government, but hadn’t been implemented.”

Juxtaposed against the violence, Jhingran noticed the quiet hope that people carried — the desire to learn. “There were parts where the administration could not even reach; schools were shut. But I got the feeling that people wanted development, they wanted their children to get educated, they wanted peace.”

Advertisement

But formalising the education system while a majority of the population was holed up in refugee camps seemed counterintuitive. Jhingran, however, thought differently: “I believed that bringing back peace and a literacy campaign should be woven together.”

Elaborating on the literacy campaign, he shares how it targeted adults aged 15 to 45 years, intending to help them learn to read and write. Teaching adults meant recalibrating the fundamental yardsticks of basic education. The goal was hefty, but not impossible. Jhingran explains, “We created a team of 3,000 volunteers in the district. Mainly youth — young women — these were people who came forward volunteering to conduct literacy classes for the adults. In the bargain, we also made them agents of peace.”

From songs composed in tribal dialect to peace committee meetings, a proper plan was instated. And, in nine months, the violence gave way to peace. “There was a demand for good quality school education,” Jhingran shares, “The people demanded that schools improve, teachers attend school regularly, that school building infrastructure be improved, and children actually learn.”

The district authorities remarked on the campaign’s success. Uddalak Datta, part of the Assam civil service and an extra assistant commissioner (EAC) of Kokrajhar at the time, shares, “I had never imagined that something so transformational could happen in the system. Kokrajhar district was affected by extremism. People were so scared, no one wanted to stay there because of the violence. But Jhingran transformed their mindsets.”

He continues, “Jhingran inspired everyone. He involved everyone. He saw who could work in which department of the campaign. People found a leader who could really motivate them and mobilise them. It was such a grand success in terms of a vibrant campaign.”

The success of the campaign affirmed Jhingran’s faith in the strategy.

Advertisement

An antidote to educational precarity

All of what is taught to a child cannot fit into the binary of their native language and the mode of instruction in school (often English). This isn’t just Jhingran’s reasoning; the view is also shared by the United Nations. A UN article, estimating that at least half of the global population is bilingual, called for “mother language-based and multilingual education as fundamental to achieving quality, inclusive learning”.

The report underscored that students learn best in a language they understand, and that children who speak the language they are taught in are 14 percent more likely to read with understanding at the end of primary, compared to those who do not. But the irony, the report highlighted, is that “40 percent of the world’s population does not have access to an education in a language they speak or understand”.

Sharing how multilingualism becomes a tool rather than a spoke in the wheel at the Language and Learning Foundation, Jhingran shares, “In a lot of primary classrooms, children stay silent; they don’t speak at all; they can’t express themselves. We stress making the oral language strong; accordingly, written and spoken language will also become strong.”

Telling the success story of Sapna (name changed on request), a seven-year-old from Haryana, whose mother tongue was a dialect of Punjabi, Jhingran recalls how, despite being a bright child, she was a passive student. Sapna would hardly participate in class. Her teachers often described her as reticent. But today, she’s one of the most vocal students in the classroom. Sapna doesn’t shy away from asking questions or from answering what she knows.

What brought about the transformation?

“The teacher provided a bridge; she used a language most familiar to the child (the home language) to help her understand the school language well. This technique is helpful in grasping oral concepts. It’s done in a way that the teacher builds the child’s vocabulary using a dialect that they are familiar with, such that the child eventually starts picking up the other language (the school language),” Jhingran adds.

He mentions that while reading and writing are prioritised in the school language, comprehension skills are emphasised in the home language. “We train teachers to systematically build vocabulary and the child’s overall ability. It’s a transition, from one language to the other.”

Sapna’s academic success underscores how powerful this approach can be.

And just like that, Jhingran hopes for an India where language will stop being a barrier; instead, becoming a bridge.

All pictures courtesy Language and Learning Foundation