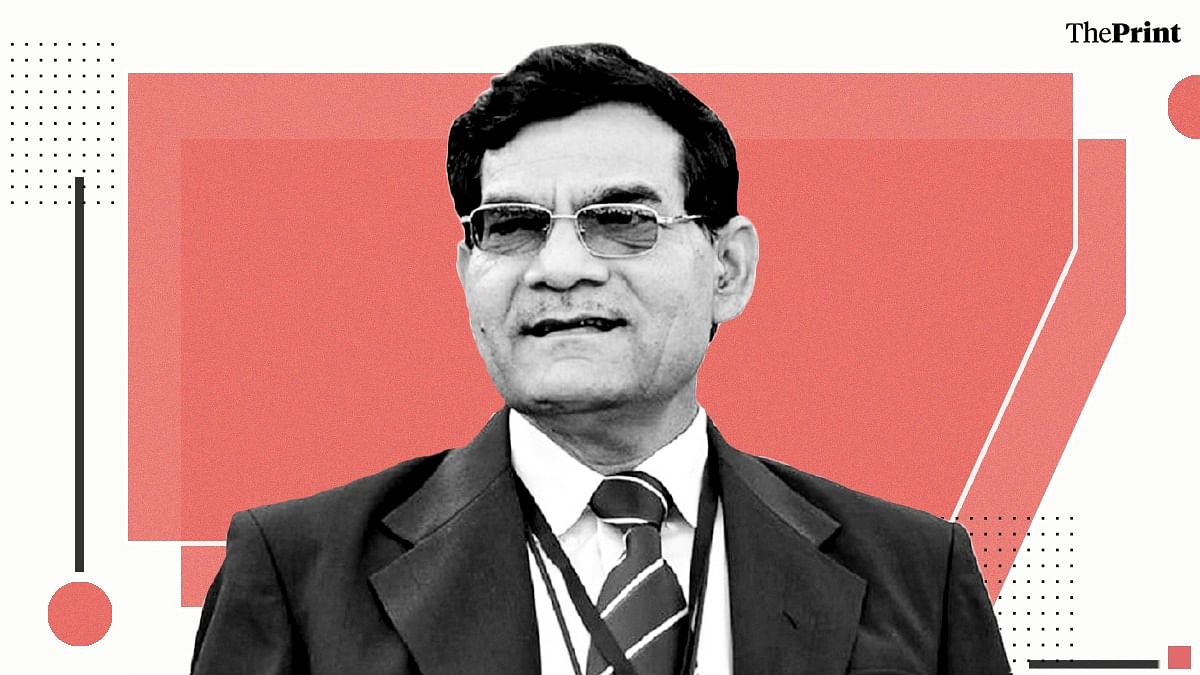

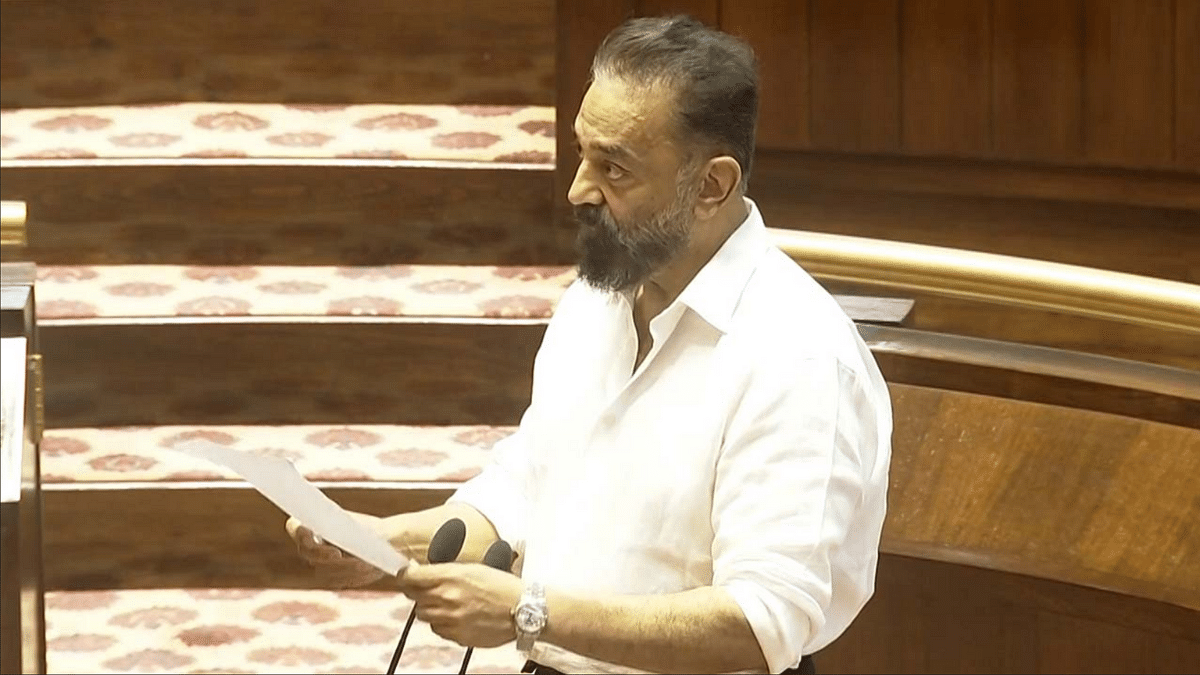

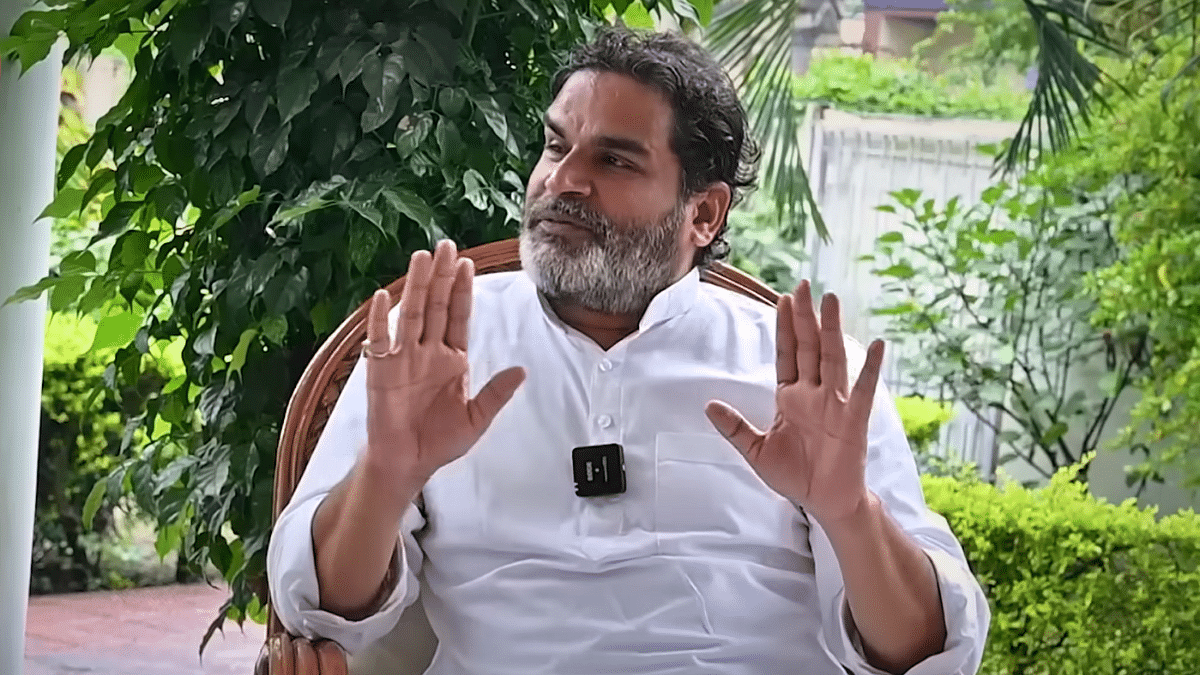

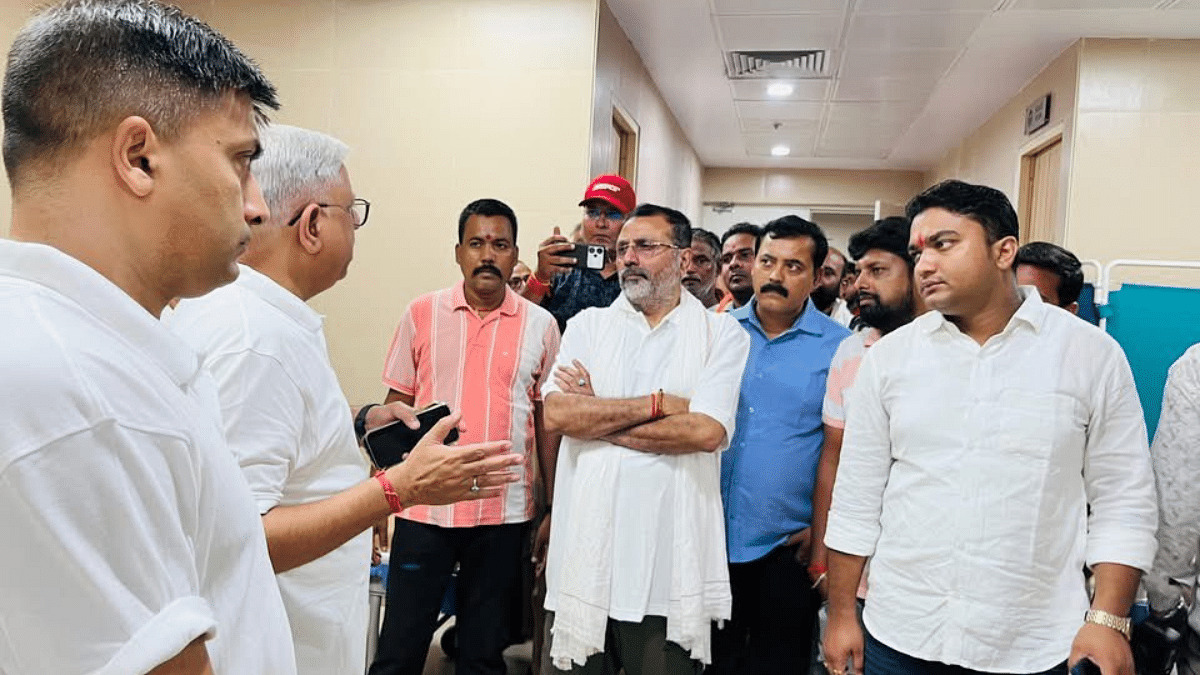

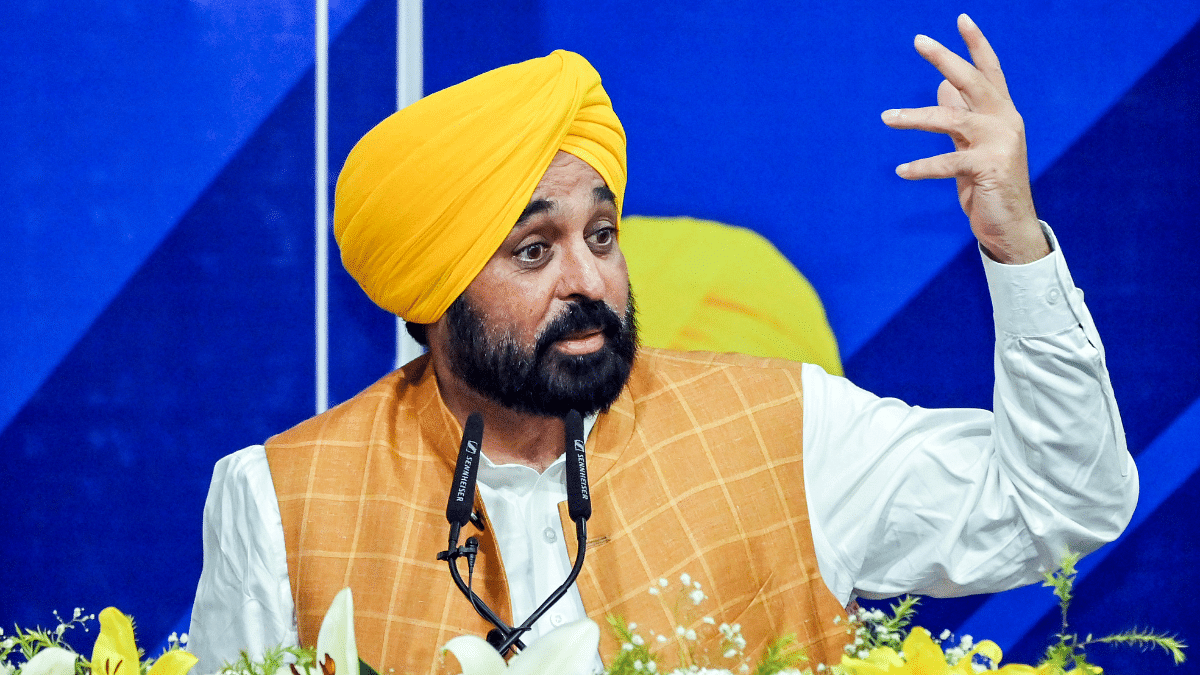

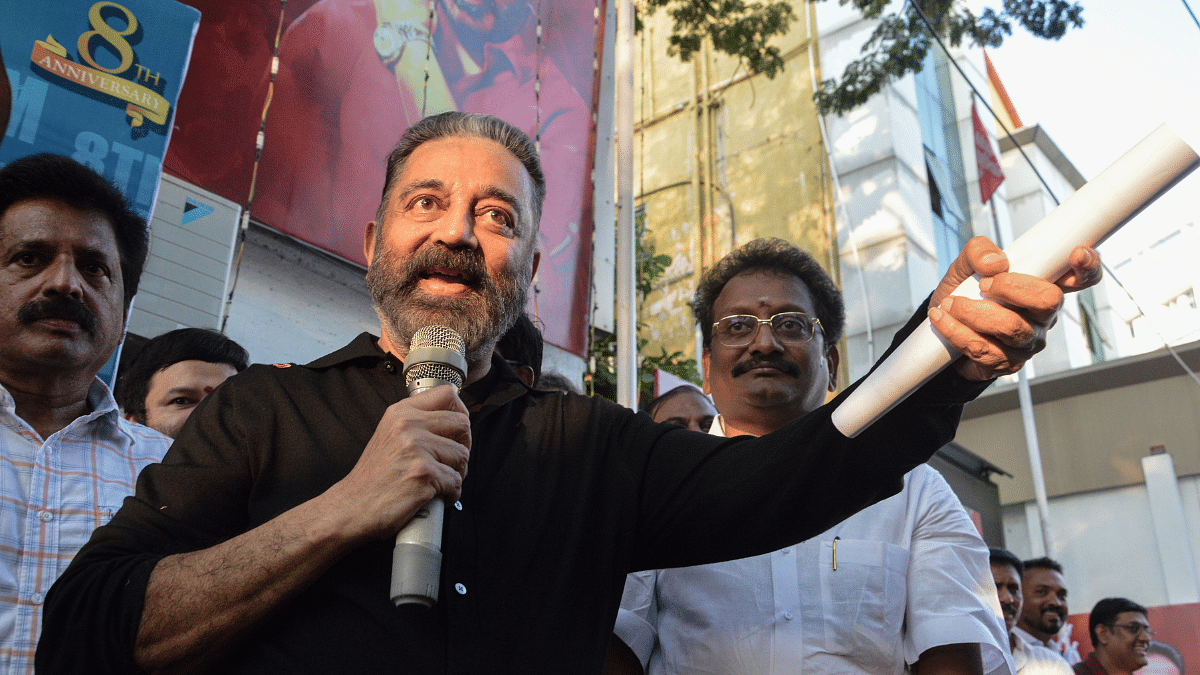

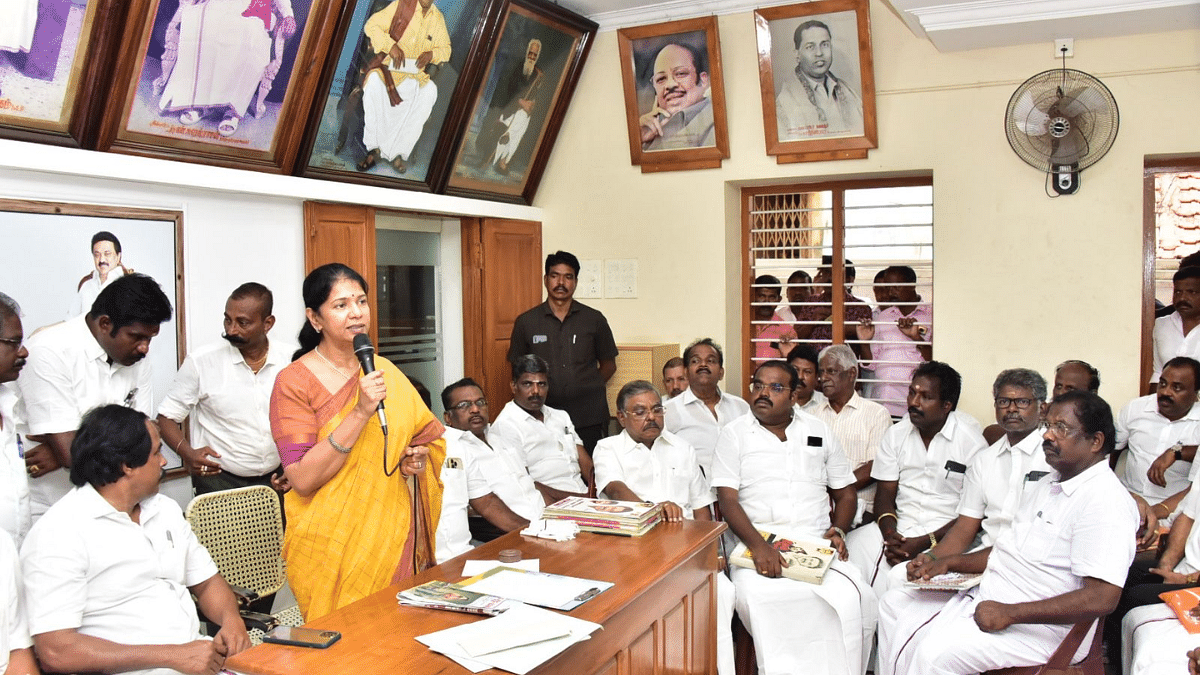

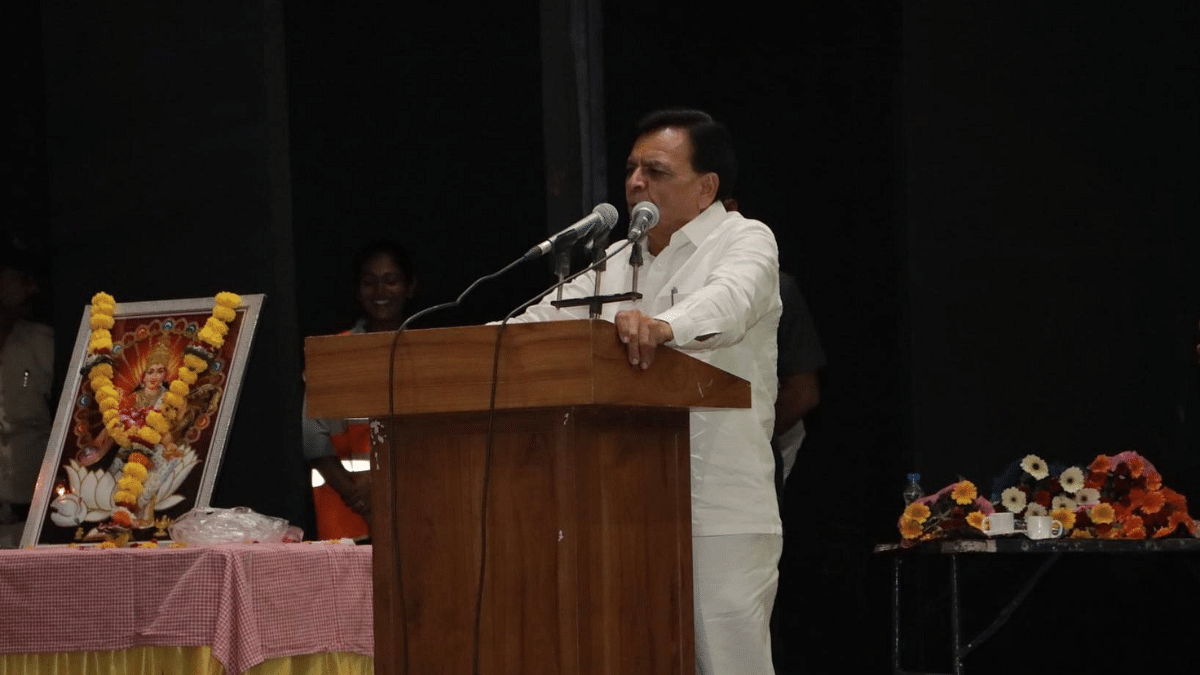

Tamil Nadu chief minister M K Stalin has been in hospital since July 21. Newspapers, including The Times of India, quoting medical bulletins from the hospital, said he underwent investigations, including a diagnostic angiogram and a therapeutic procedure to correct variations in his heartbeat.

Soon, there were discussions in some circles about why we hadn’t specified the therapeutic procedure (as a Tamil daily had). Some said newspapers didn’t have the “guts” to report the details. I beg to differ.

We knew exactly what the procedure was. It was an informed decision not to go into the details, following guidelines on patient confidentiality. Would we have followed the same guidelines if the patient were not a VIP?

The answer is yes, unless the procedure is news (here, again, the patient’s identity would be revealed only with consent and if it adds value to the story).

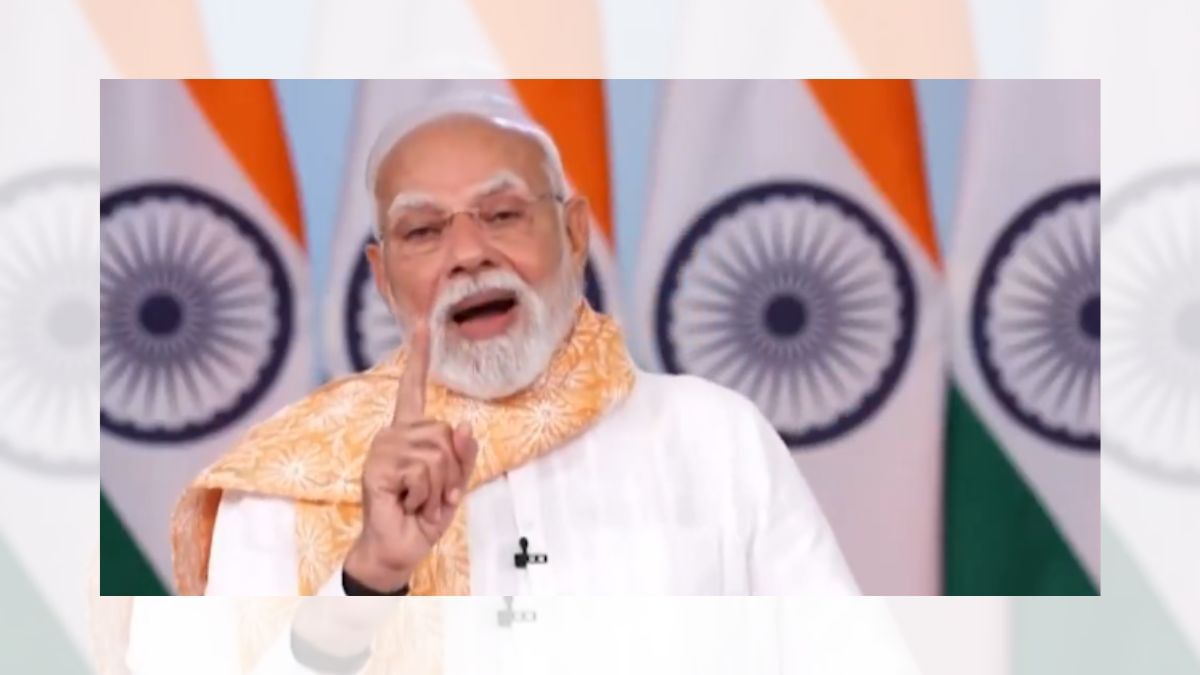

Has the media always followed these guidelines? No. In the early 2000s, a news magazine had A B Vajpayee on the cover, with the headline that read something like this: How healthy is our PM? It had a photograph of Vajpayee – as in an anatomy textbook – with a dozen body parts marked with specific ailments. I don’t remember Vajpayee protesting.

He lived another 15 years or more.

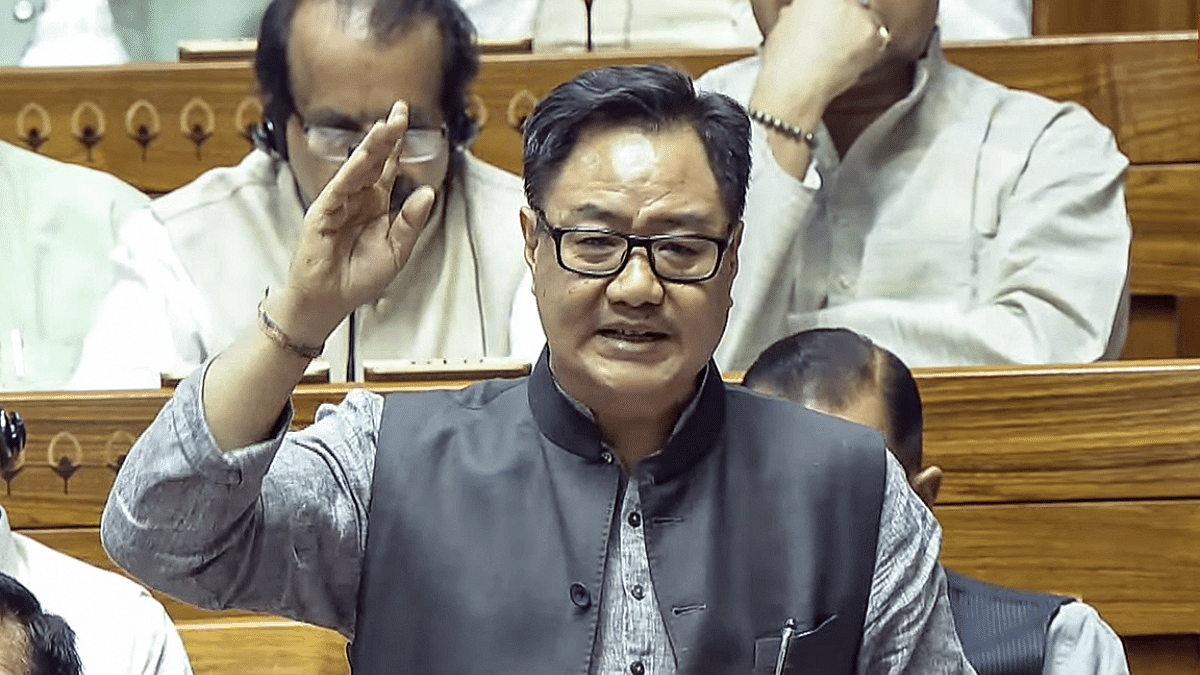

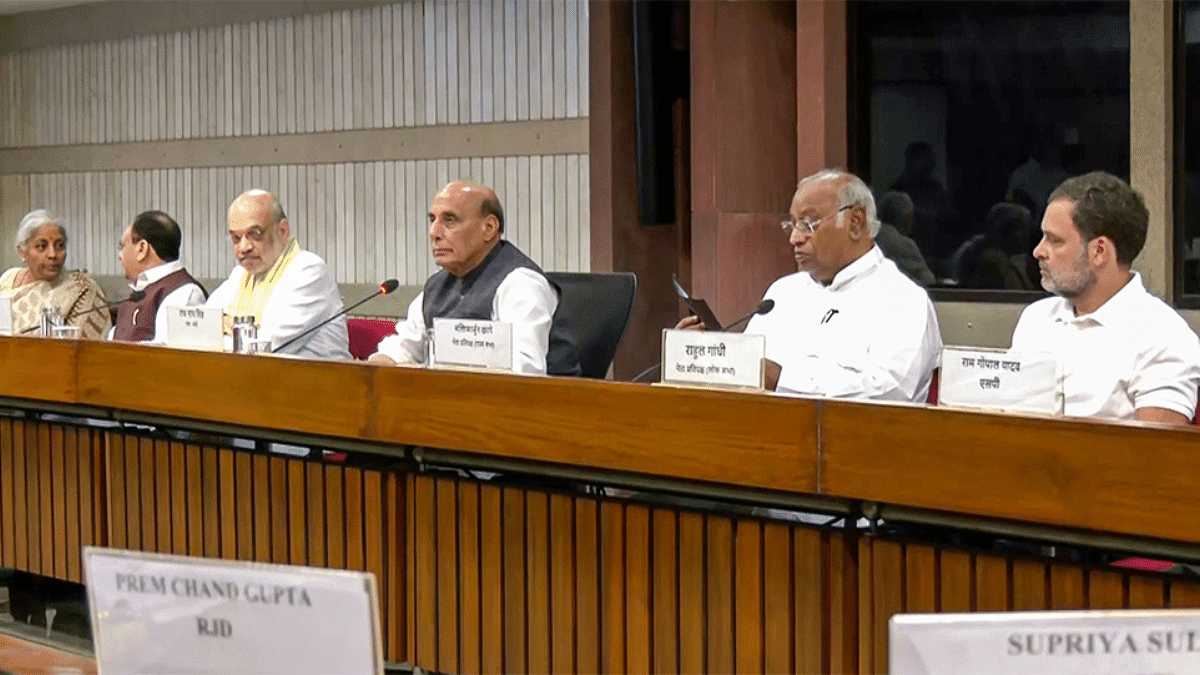

Things have changed. Today, the mainstream media follows internationally accepted guidelines while reporting on the health status of people. Shouldn’t the public know about the health of public figures, especially those who make decisions that impact public life?

I believe we should know how healthy our lawmakers are, but we aren’t entitled to their diagnosis sheets. And here comes the importance of official health bulletins that give out ample and accurate information without breaching patient confidentiality.

The medical bulletins on Stalin kept this promise. It said the results of the procedure were normal and the chief minister would resume work in two days.

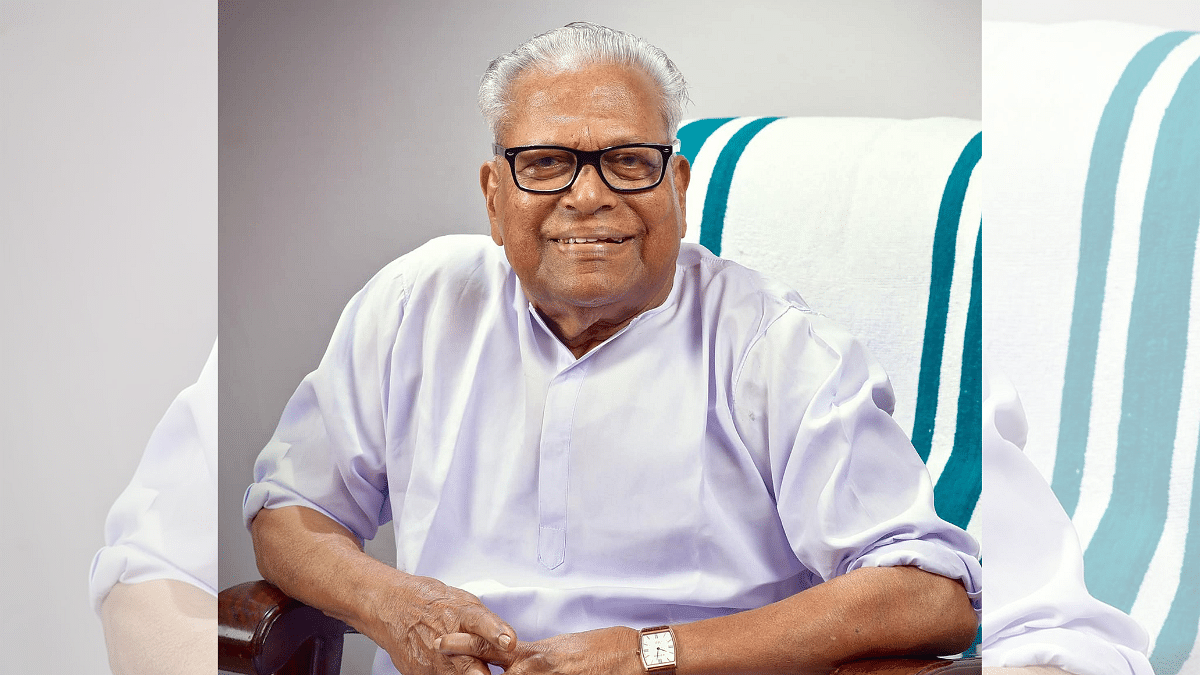

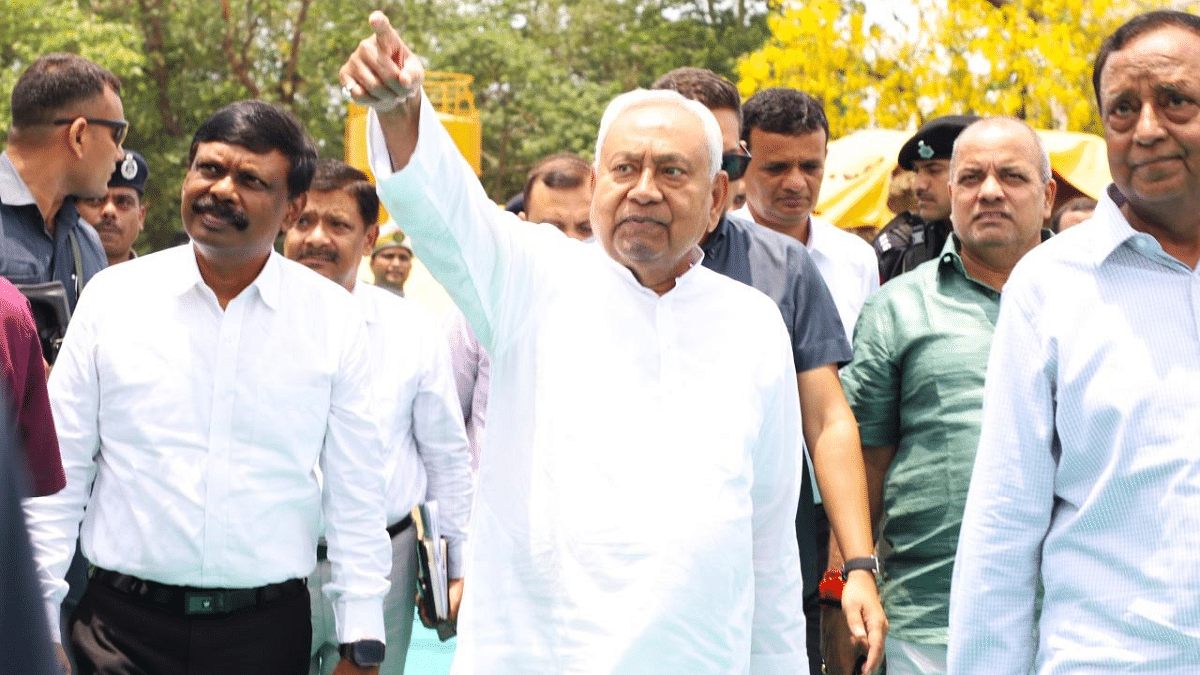

Not all medical bulletins are forthcoming when the patient is a high-profile person. Senior journalists who have covered former chief minister M G Ramachandran’s health remember the hospital putting out regular health bulletins that gave necessary information. But after his return from the US (where he underwent treatment) in Feb 1985, information dried up and speculation ran high. MGR made several more visits to the US for treatment and died two years and 10 months later.

Medical bulletins during J Jayalalithaa’s hospitalisation were sometimes inaccurate and misleading. On September 22, 2016, a bulletin said she was hospitalised with complaints of fever and dehydration (it turned out that she had fainted at home); two days later, it said she was on a normal diet.

On September 29, the hospital said the CM was recovering well. On Oct 6, a bulletin said she was on respiratory support. Her condition see-sawed between then and her death on December 5, 2016 (On November 13, Jayalalithaa released a statement saying she had “taken rebirth because of people’s prayers”), but probably on orders from the patient or her caretakers, the hospital sometimes played down the criticality of her condition.

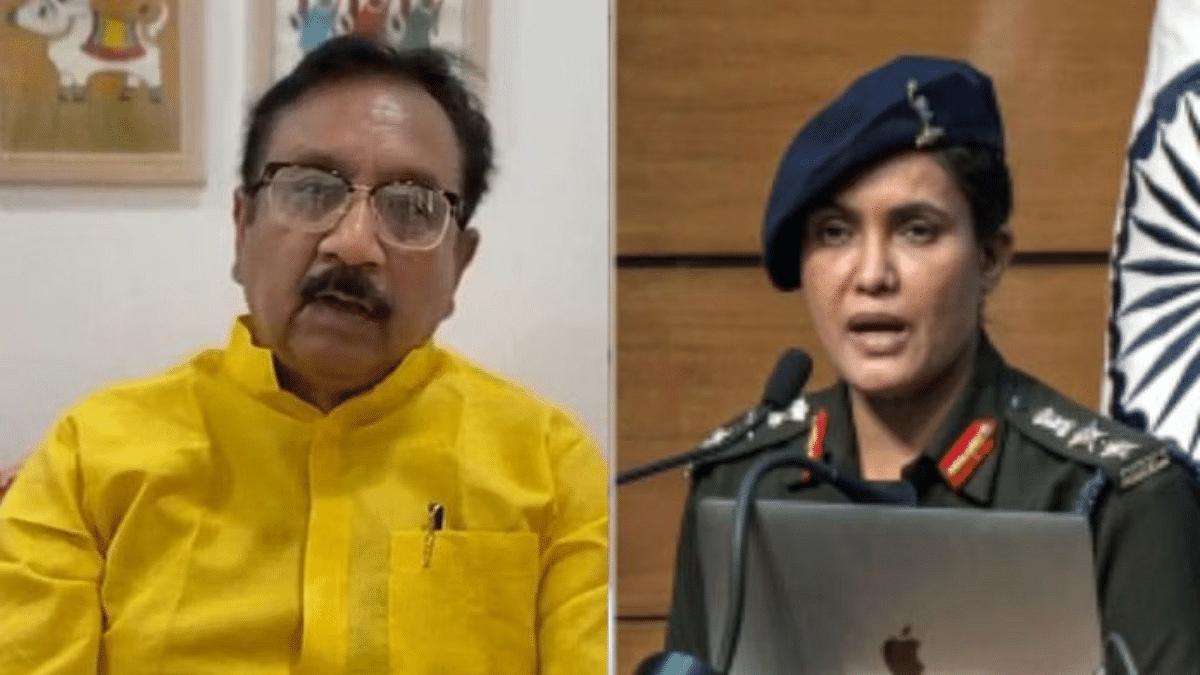

The worst a bulletin can do is give inaccurate information. We don’t expect the hospital to go on record when a public personality undergoes such a critical procedure as, say, ECMO (when machines take over the functions of the heart and lungs), but it is imperative that the media is informed about the seriousness of the condition.

A good health reporter has no difficulty in keeping track of a VIP’s condition in a hospital. What a newspaper does with the information depends on how responsible it is – to the patient and the public.

Disclaimer

Views expressed above are the author’s own.

END OF ARTICLE