When Scientific American first came out in August of 1845, the universe was far different from what it is today.

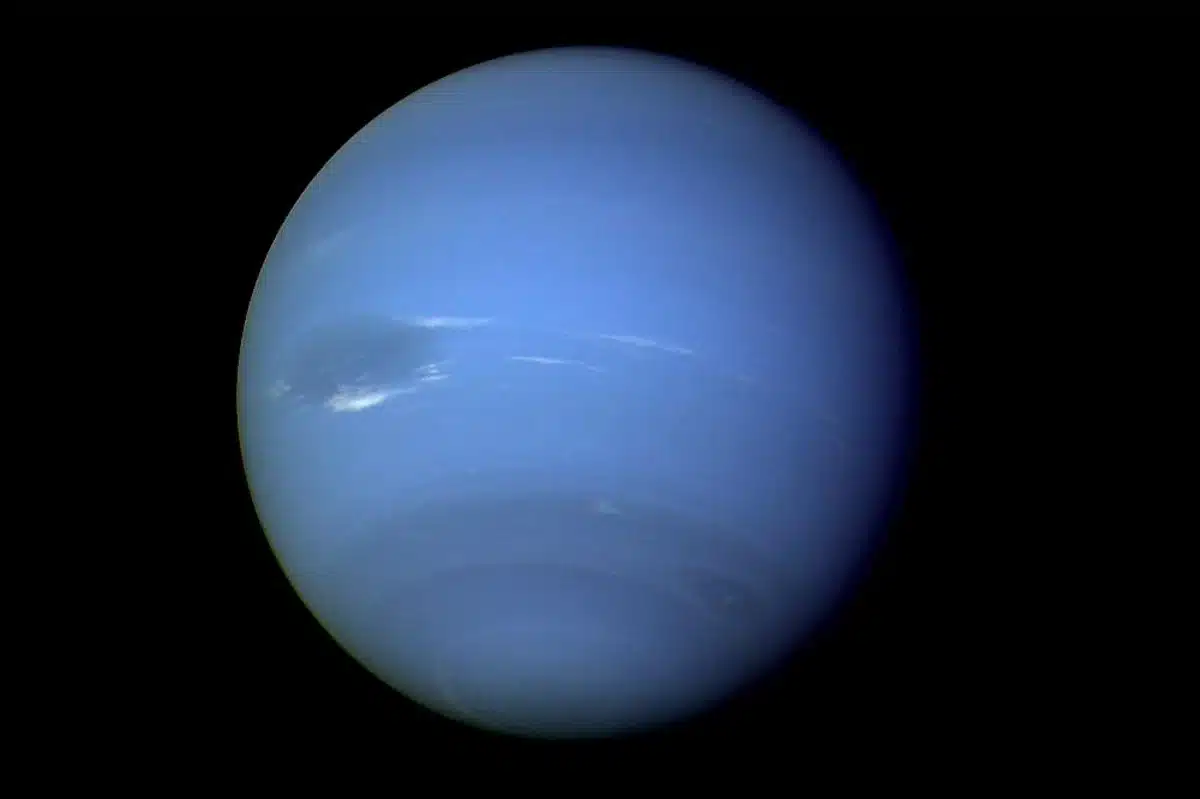

Humankind hardly understood how stars were made, the way our own solar system was created, or even the number of planets revolving around the sun. Interestingly enough, the magazine was already in print a year before the official discovery of Neptune, the farthest planet from the sun.

Saturn was once thought to be the most distant planet from human knowledge. All that changed in 1781, when astronomer William Herschel discovered Uranus by mistake, thinking it a comet. The drama of planetary discovery, however, came much later, as Uranus started acting up in its orbit. Its deviations from anticipated trajectories convinced astronomers that another unseen world must be pulling it with its gravity.

The Hunt for a Hidden Planet

Finding such a dim, faraway planet was no easy feat in the mid-19th century. Telescopes were rudimentary, and astronomers relied on hand-drawn star maps. Still, mathematics provided a breakthrough. By calculating Uranus’s orbital irregularities, astronomers could predict where this mysterious new planet might lie.

Two individuals independently tackled the problem: British mathematician John Couch Adams and French astronomer Urbain Jean Joseph Le Verrier. Adams’s partial calculations were initially ignored by British astronomers, but Le Verrier’s work, released in 1846, generated a sensation in France.

On 23 September 1846, astronomer Johann Gottfried Galle, with the help of Heinrich Louis d’Arrest at the Berlin Observatory, pointed a telescope in the direction indicated. During the evening of this day, they discovered Neptune to be within a degree of Le Verrier’s computed location. Its discovery was celebrated as a victory for mathematics, as opposed to Uranus, which had been discovered largely by chance.

Missed Opportunities and Irony

Ironically, Neptune had been seen numerous times prior to official discovery. Records indicate it was seen by Galileo in 1612 and 1613, but he identified it as a star. Even closer to the time of discovery, Cambridge astronomer James Challis accidentally saw Neptune twice during August 1846 but did not recognize it. The distinction boiled down to accuracy, improved star charts and better calculations provided Galle with the advantage.

The credit question still persists. While Le Verrier is frequently credited with discovering the planet, the British insisted that Adams be given credit. Historians continue to debate whether or not Adams’s findings were precise enough to really qualify as co-discovery.

From 1846 to Now

In the 180 years that have passed, our knowledge of the universe has increased beyond wildest dreams. Neptune, a mathematical abstraction back then, was investigated at close range by NASA’s Voyager 2 spacecraft, and it uncovered its violent weather systems, feeble rings, and strange moons. Thousands of exoplanets, including Neptune-type worlds, have been discovered orbiting faraway stars by astronomers.

Even within our own solar system, we’ve uncovered a host of icy objects beyond Neptune, including Pluto and countless Kuiper Belt bodies. What once felt like monumental discoveries in the 19th century are now routine steps in astronomy.

Amidst all of this, Scientific American has been a steady presence, documenting scientific achievements since its inaugural issue back in 1845. The magazine debuted just prior to one of the century’s greatest astronomical feats, the discovery of Neptune, and has since documented the unrelenting human quest for celestial knowledge.

Today, in retrospect at that landmark, it’s apparent how far science communication and astronomy themselves have evolved. What once was a small dot misidentified as a star has become a thoroughly researched planet, and what once was a young publication is now one of the most valued voices in science.