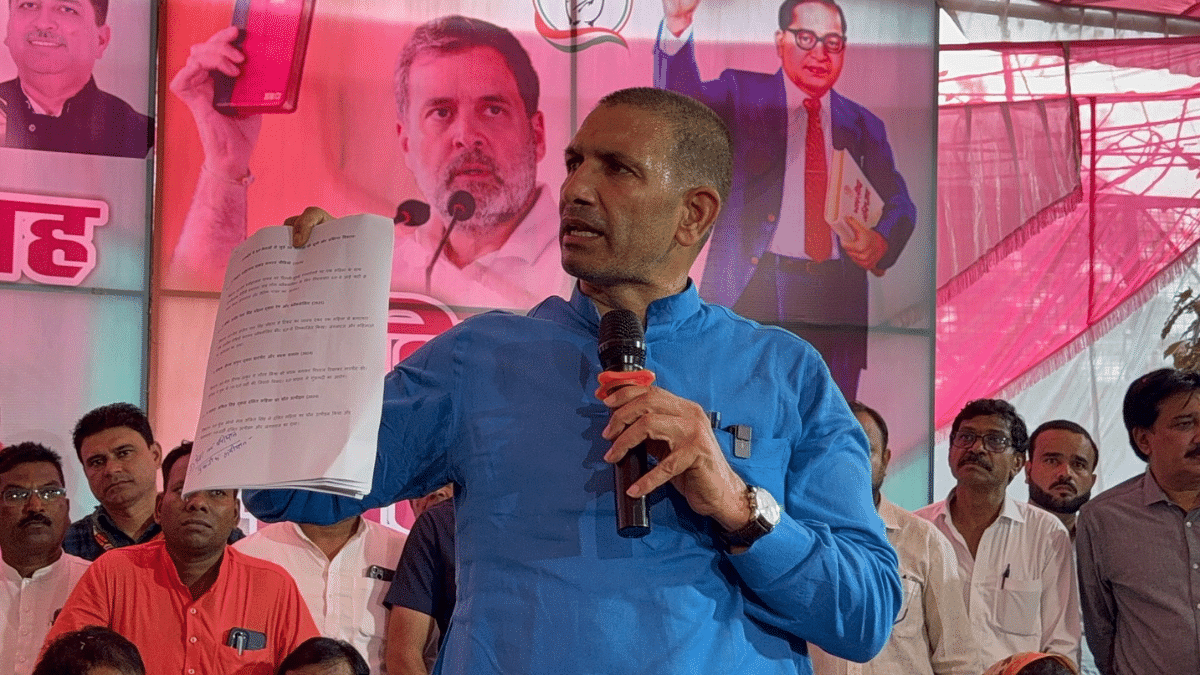

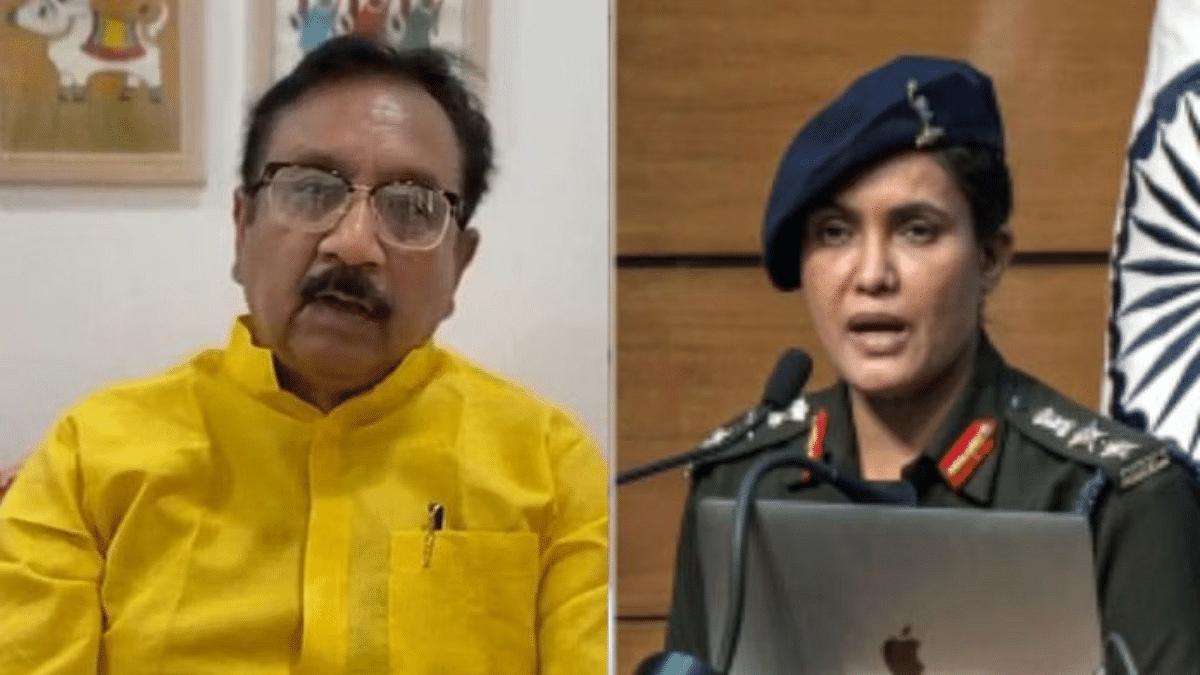

Jamdar said that ‘Lingayat’ should be a separate religion and that ‘Veerashaiva’ can be written under this in the caste section. Though Lingayats and Veerashaivas are used interchangeably, Lingayat puritans like Jamdar refuse to accept this practice even though it has become common in Karnataka’s political parlance and discourse.

Lingayats, followers of the 12th-century social reformer Basavanna, are among the most politically influential caste groups in Karnataka. Of the 23 chief ministers the state has had, only seven have been from communities other than Lingyats and Vokkaligas.

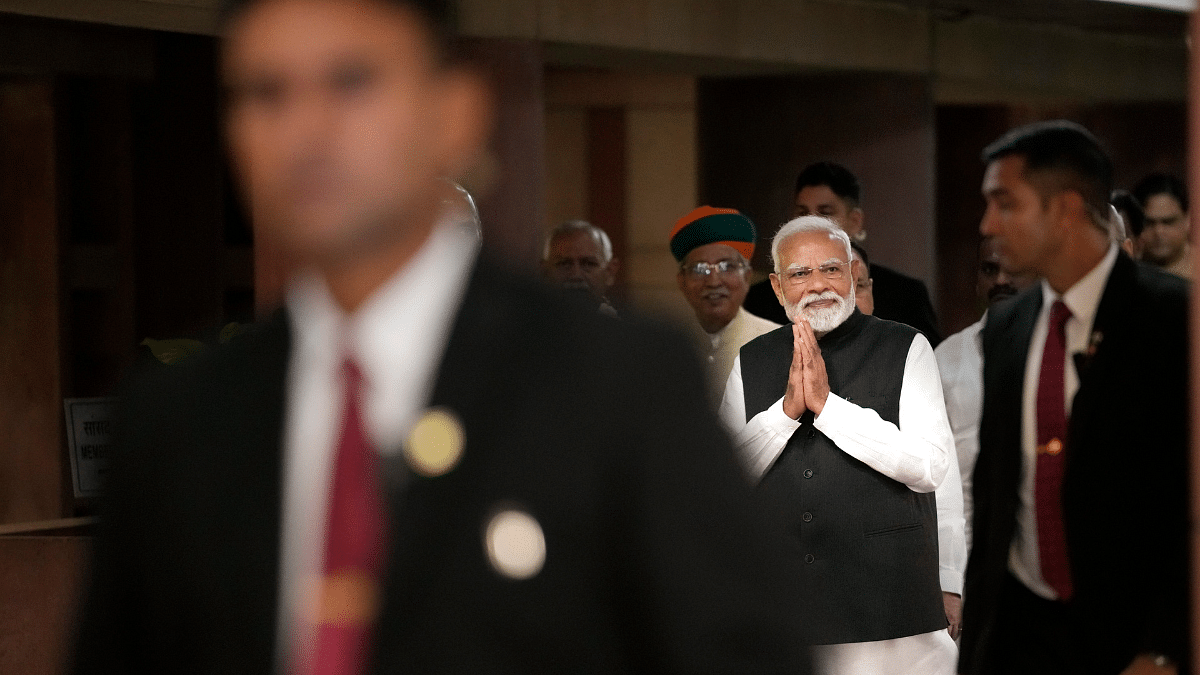

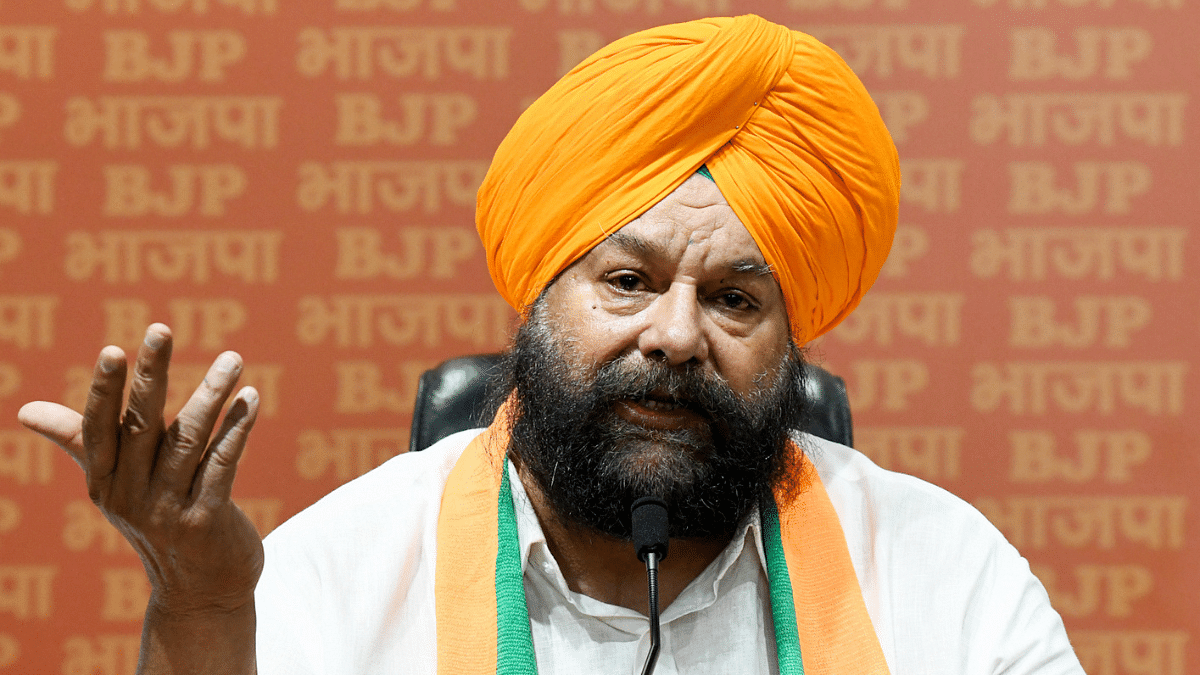

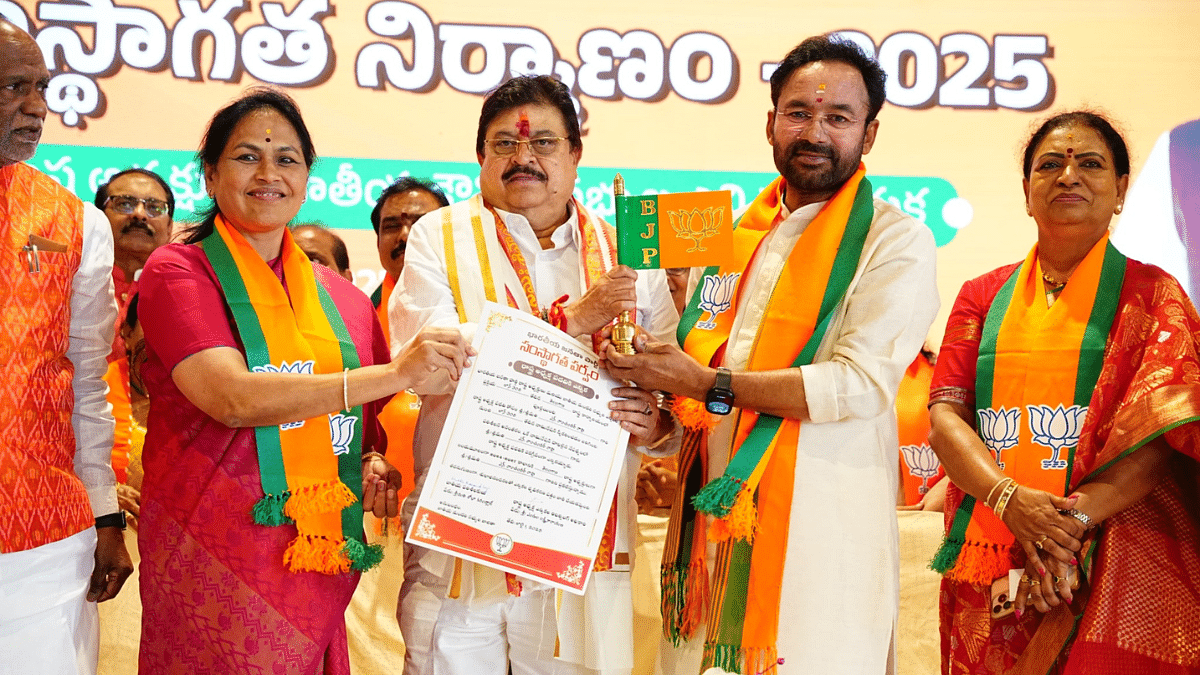

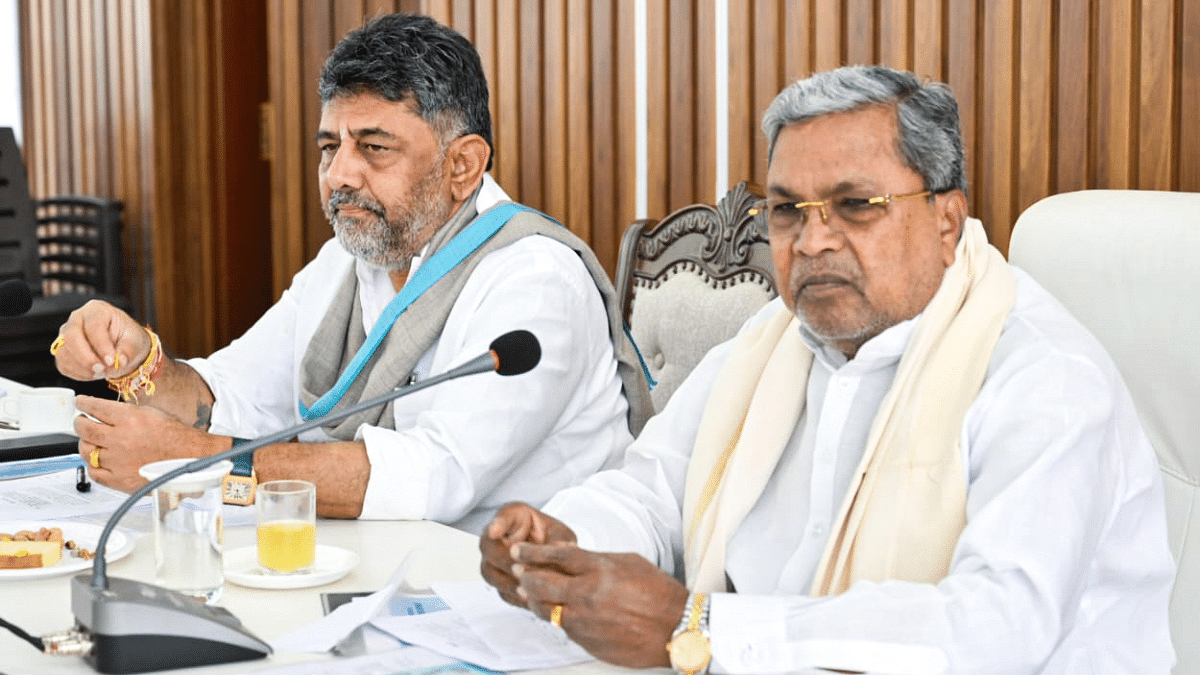

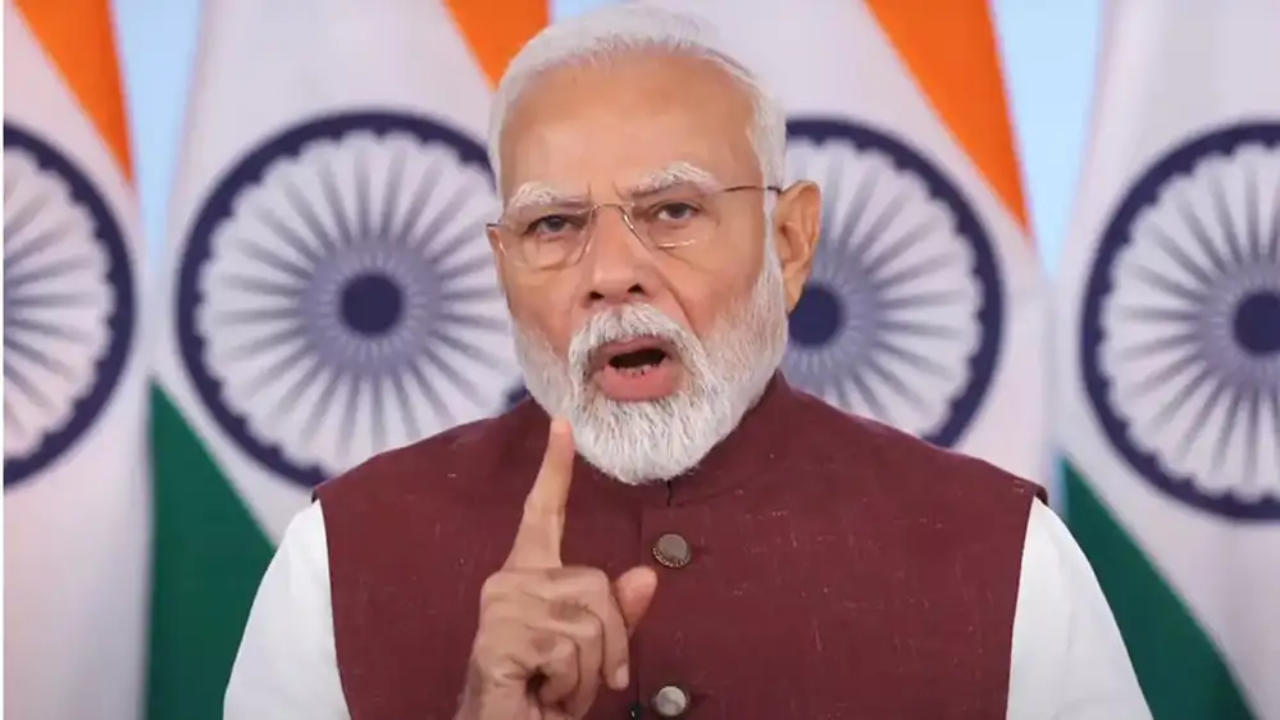

They are seen to back the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) currently, even though they have sided with the Congress and the erstwhile Janata Party in the past. But the 2015 socio-economic and educational survey, also known as the caste census, conducted by then Congress government, aimed to challenge the dominance held by a few groups.

Purported leaked census findings show that the populations of groups like Lingayats and Vokkaligas were inflated, resulting in a disproportionate share of political, social and economic capital.

The Lingayats believe that their numbers were lower than their own estimates since people identify themselves as their sub-sects and not under the larger umbrella of the community.

Several of these communities enjoyed their dominant status with no evidence to support their claims of a higher proportion of the population.

The caste census, the first since 1931, could help validate their claims and retain their influence. This could then give them greater lobbying power for better reservation benefits and greater opportunities within their political parties.

Also Read: Lingayats, Vokkaligas get lion’s share in Karnataka BJP seat allocation with 103 out of 224

Caste affiliations trump party lines

For political leaders in Karnataka, loyalty to the community often trumps political affiliations.

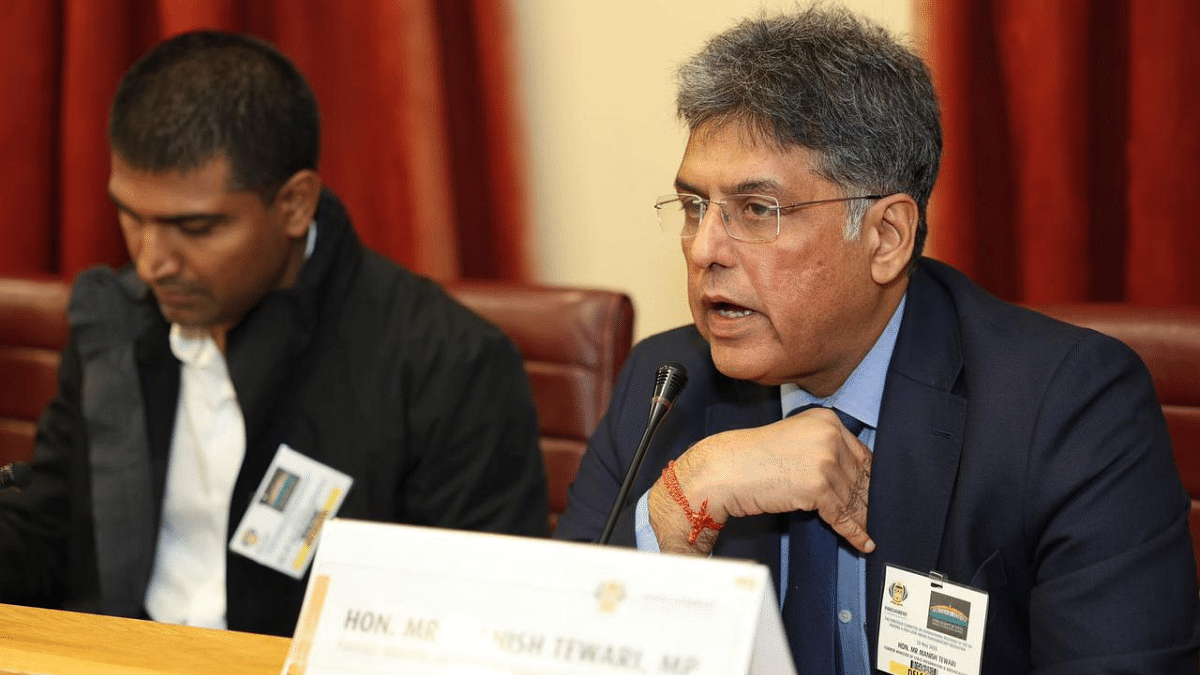

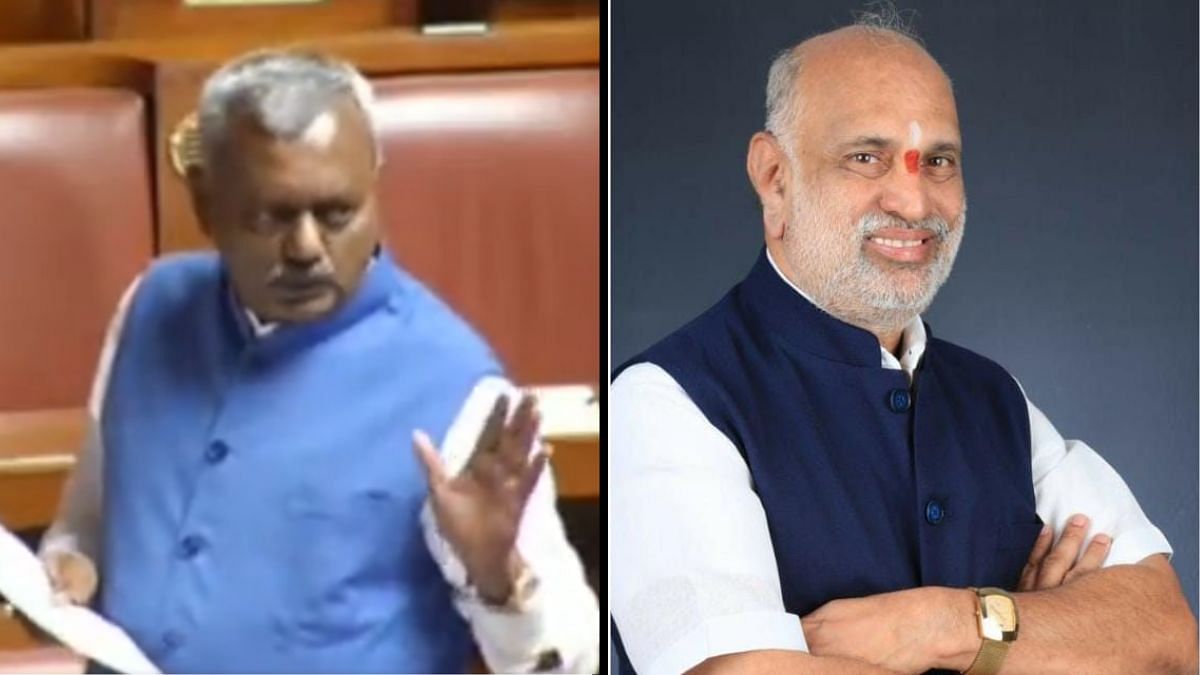

For instance, the JLM is headed by the BJP’s Basavaraj Horatti, the chairman of the legislative council, but M.B. Patil, a senior Congress leader and cabinet minister in Siddaramaiah’s council of ministers, is its working president.

Similarly, the AIVM is headed by veteran Congress leader Shamanur Shivashankarappa and its secretary general is Eshwar Khandre, Patil’s colleague in the cabinet. But it also has BJP leaders like Prabhakar Kore and Shankar Bidari who earlier served as Karnataka’s DG & IG.

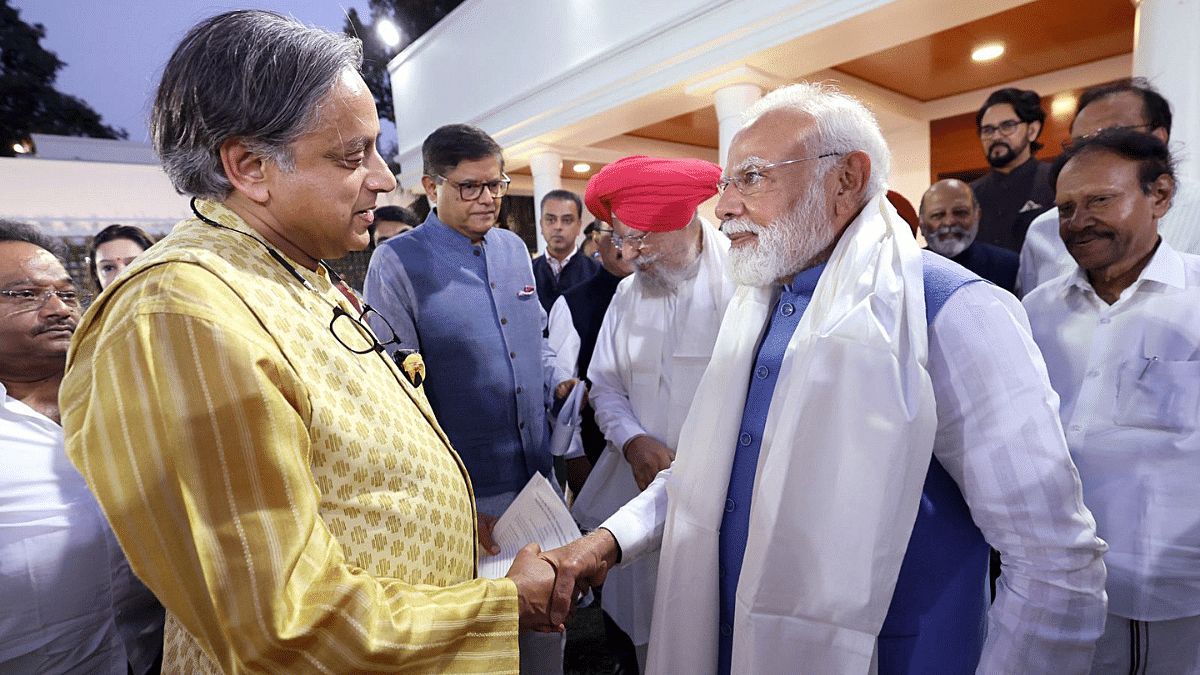

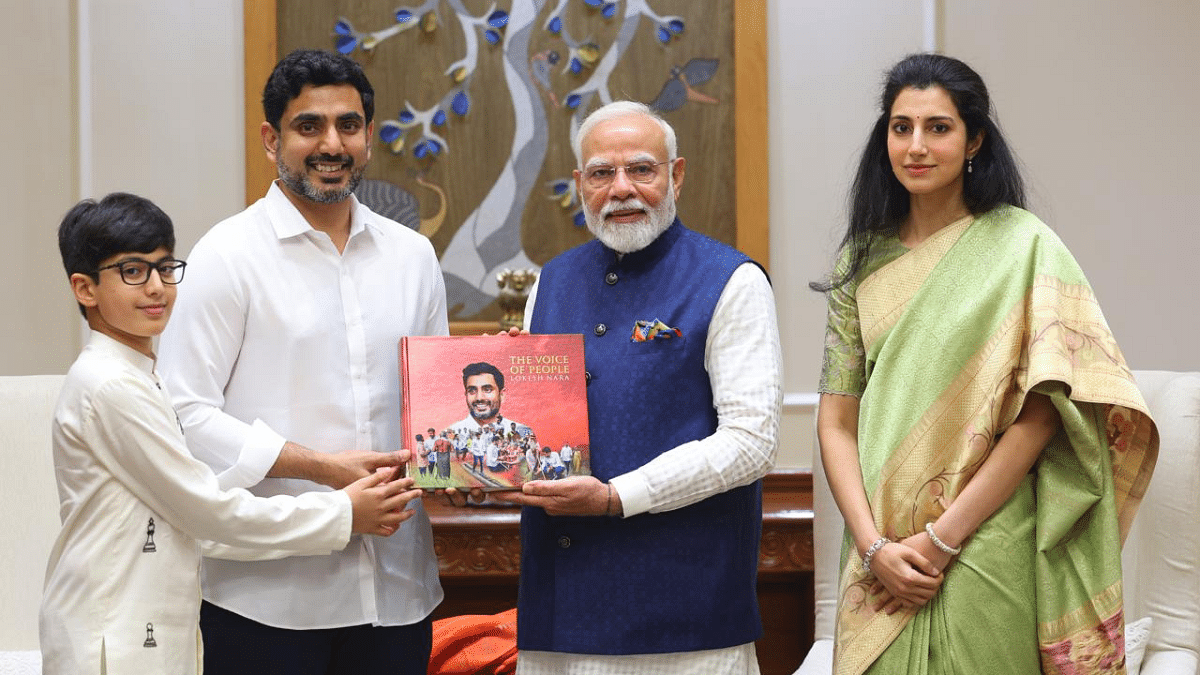

Leaders like B.S. Yediyurappa have relied as much on the community as the party. Even marriage alliances are struck between leaders from different political parties, but within the same community.

Patil’s son is married to Shivashankarappa’s granddaughter. Senior BJP leader Jagadish Shettar’s son has married another granddaughter of Shivashankarappa, indicating the importance placed on the community that cuts across party lines.

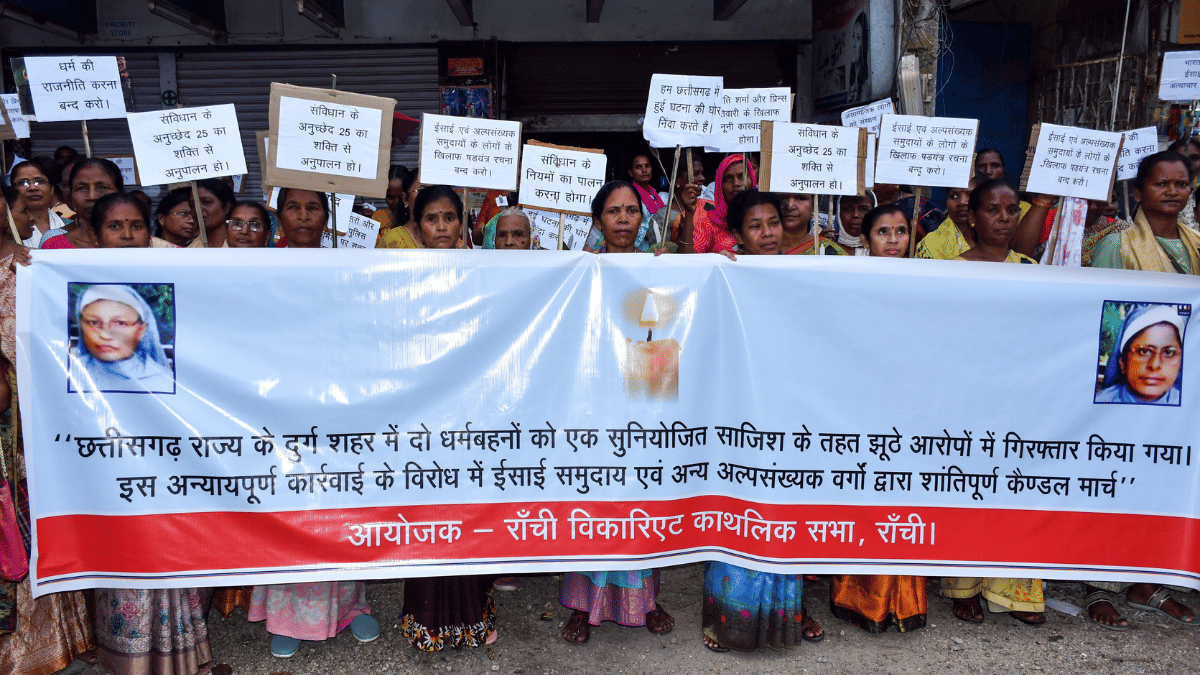

But both Patil and Shivashankarappa have been on opposite sides of the minority religion debate.

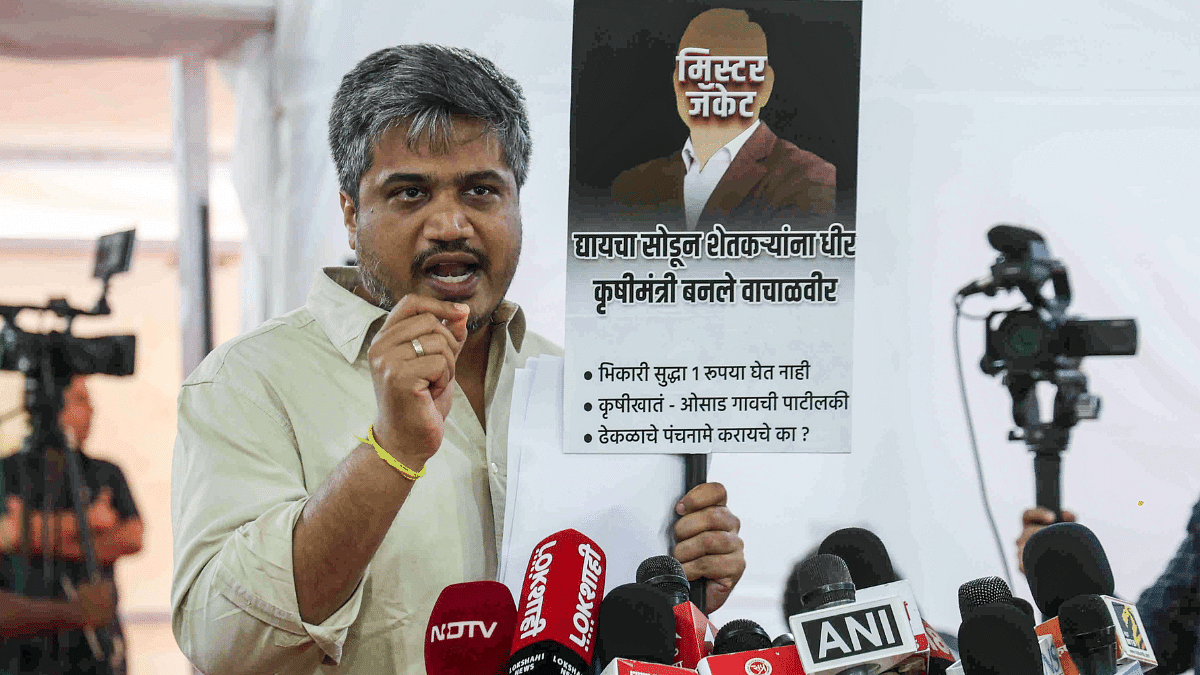

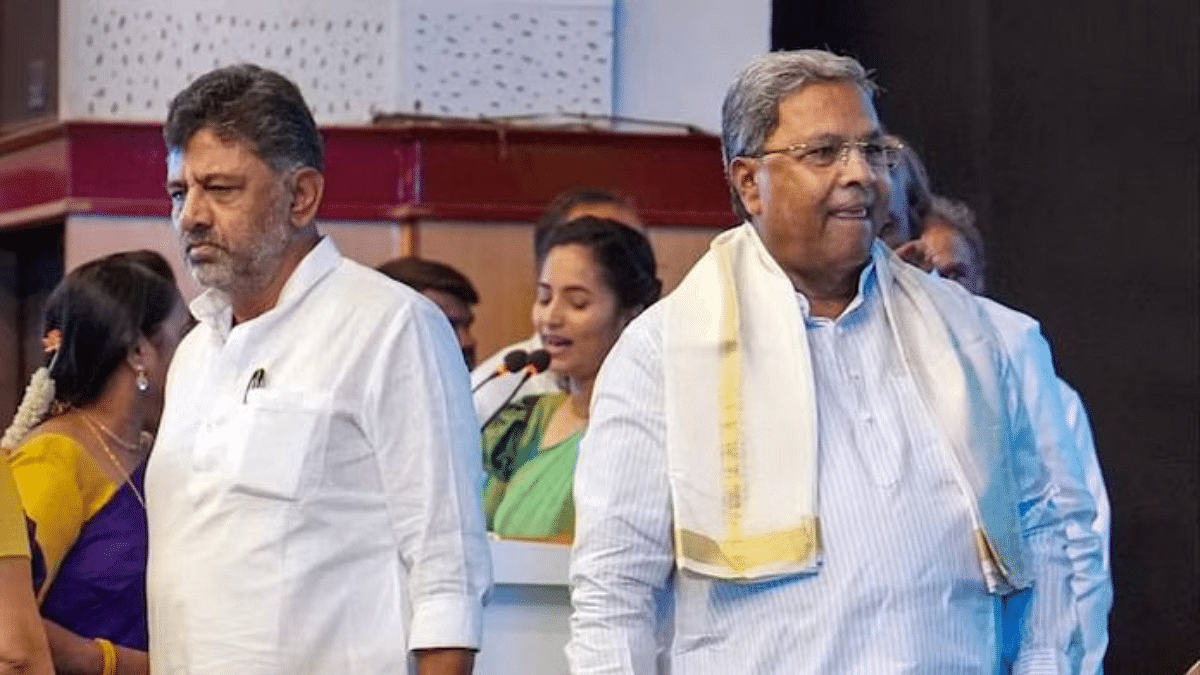

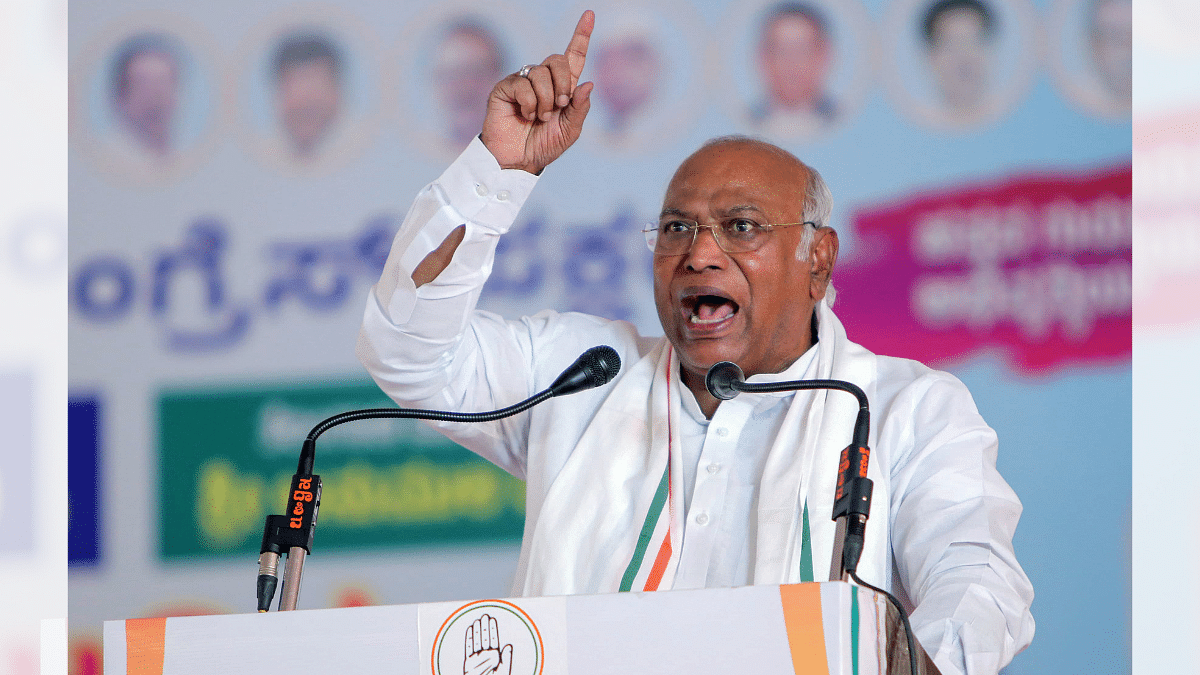

Barely a month before the 2018 assembly elections, Siddaramaiah, on the advice of Patil and a few others, accorded the minority religion tag to Lingayats. But he decided to make a distinction between Veerashaivas and Lingayats, which the Yediyurappa-led BJP projected as an attempt to “break Hindu society” and the Congress lost power.

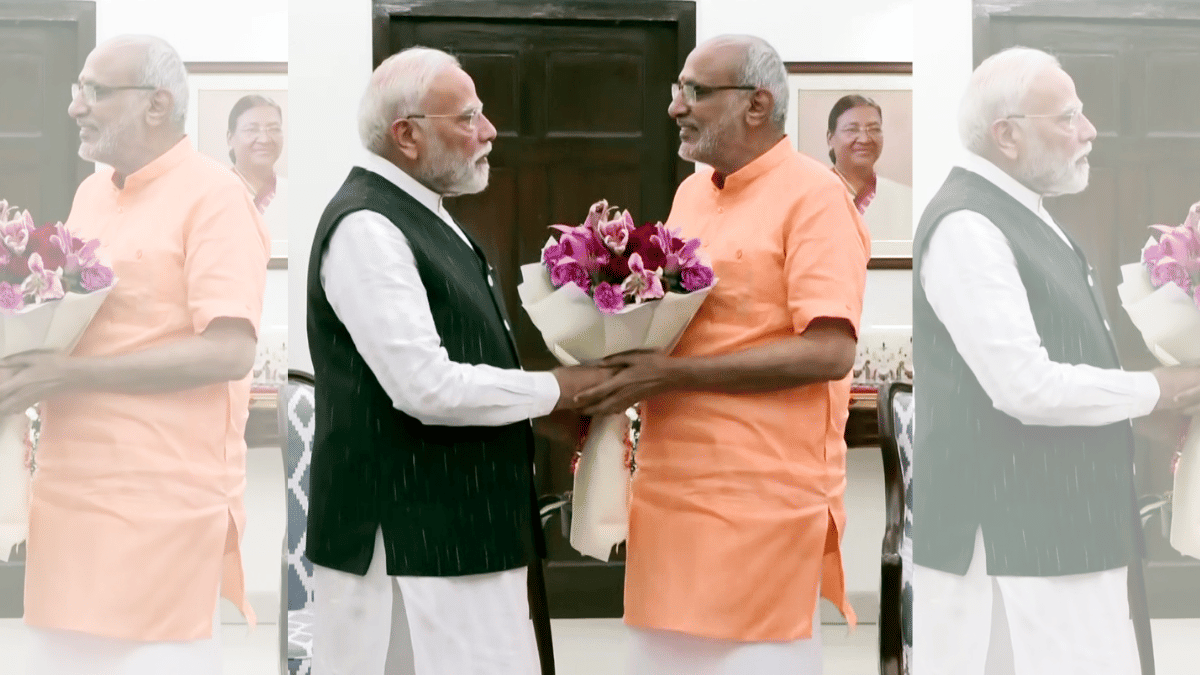

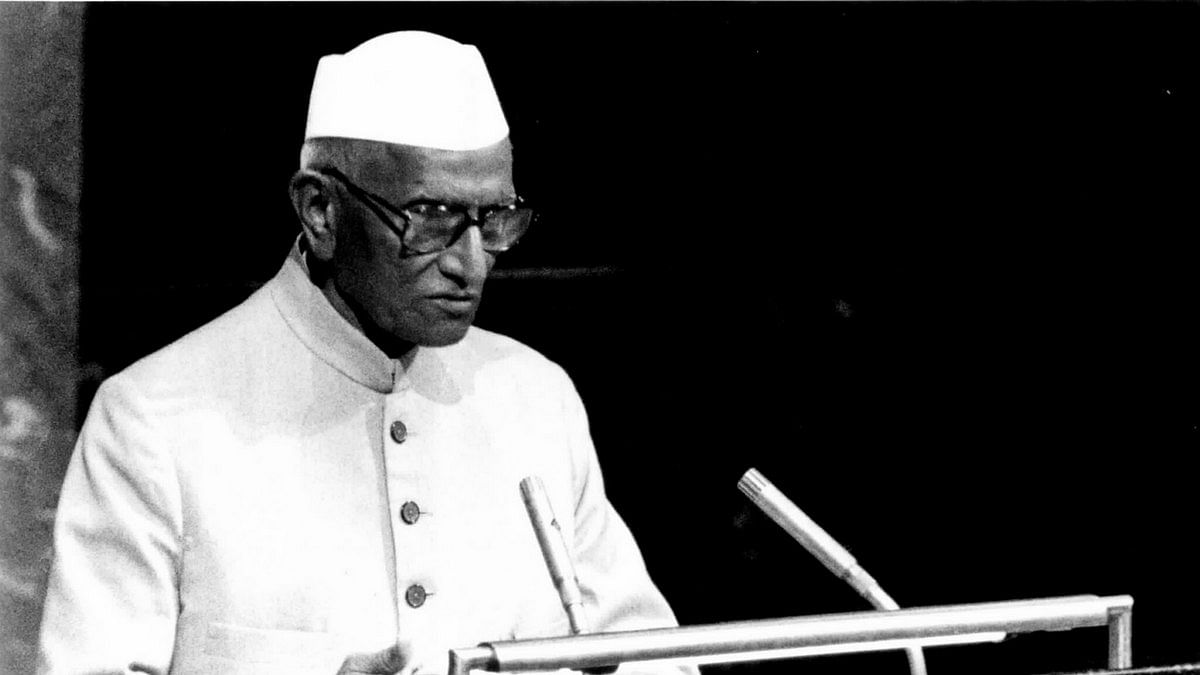

Earlier, in 2013, the All India Veerashaiva Mahasabha had submitted a memorandum to the then Prime Minister, Manmohan Singh, to recognise the Veerashaiva Lingayats as a separate religion in the census. Yediyurappa was one of the signatories.

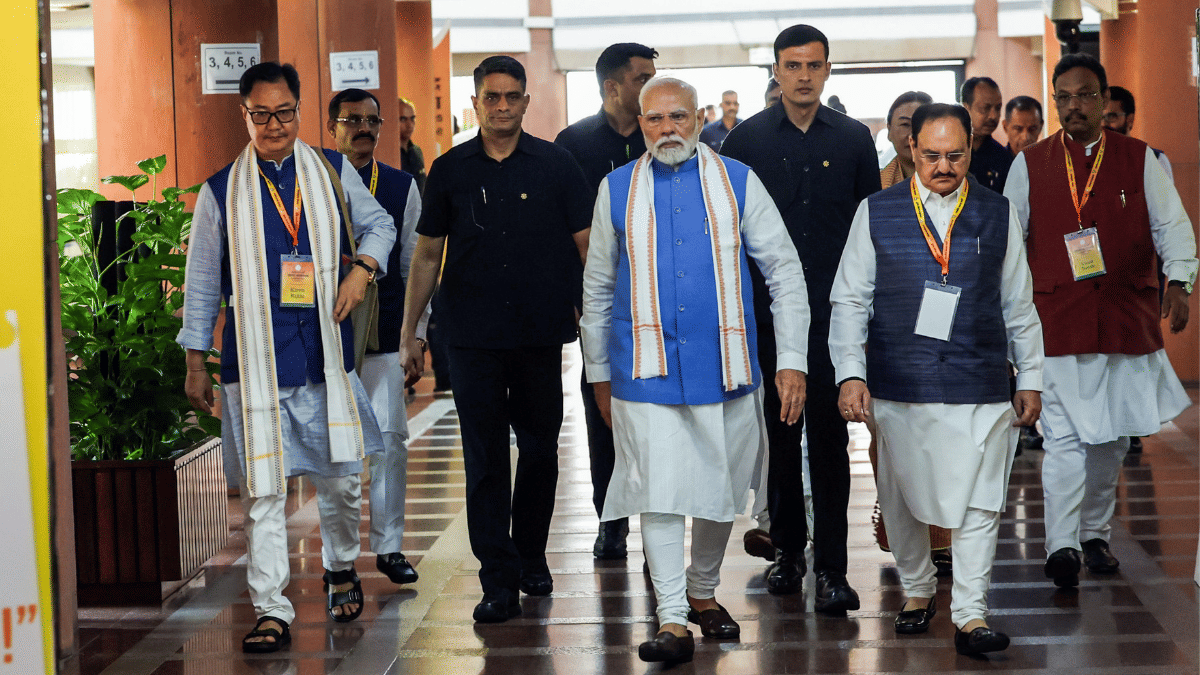

This time around, the BJP is yet to react to AIVM’s decision. “We took a stand on the issue in 2018, but there is some indecisiveness this time around. We are yet to even discuss the Mahasabha’s decision, let alone take a stand,” said one BJP leader, requesting anonymity.

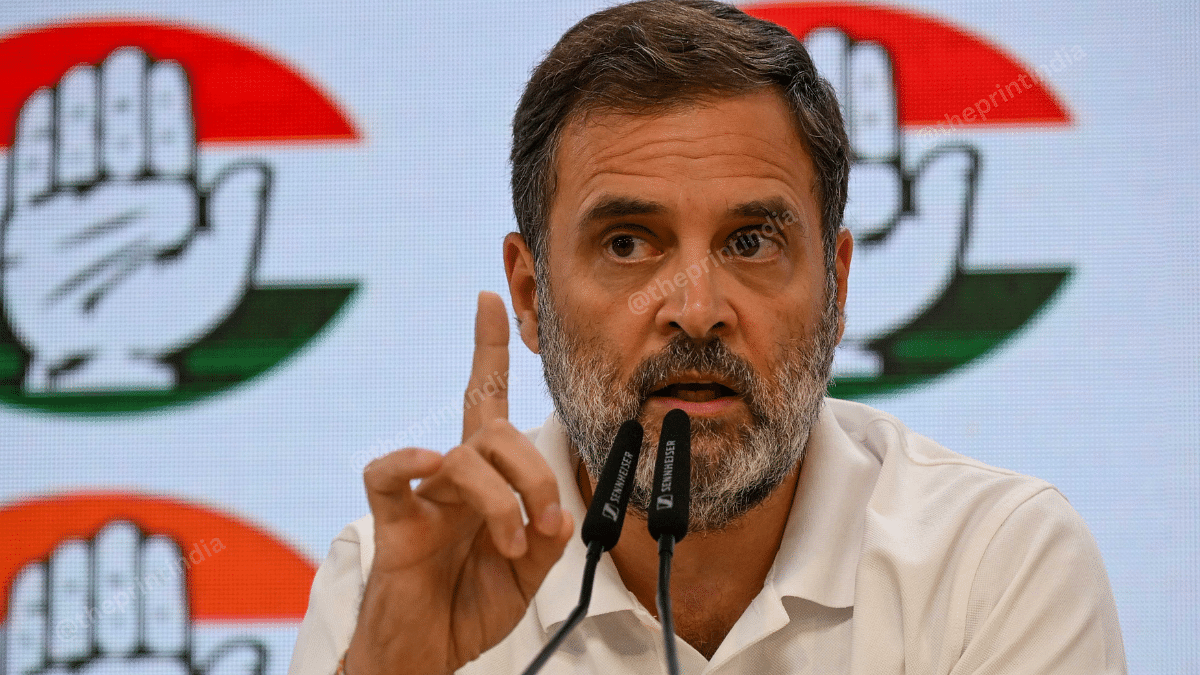

The Congress, too, is being careful not to be seen as the catalyst in the revival of the demands.

Who are the Lingayats

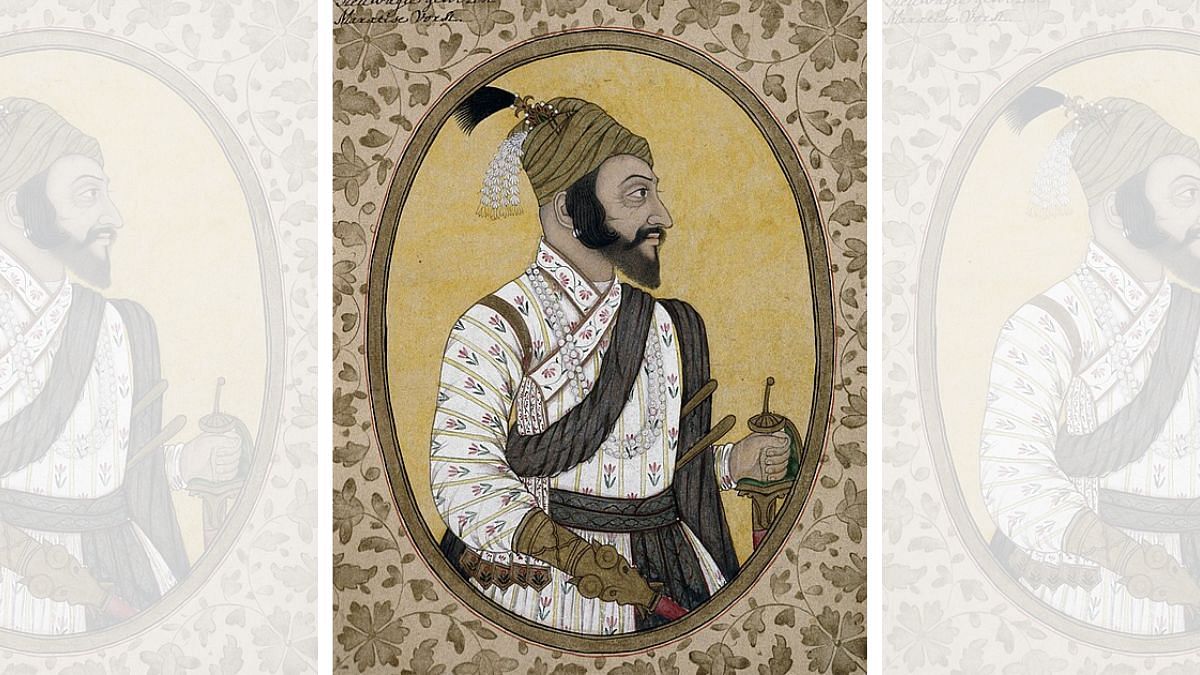

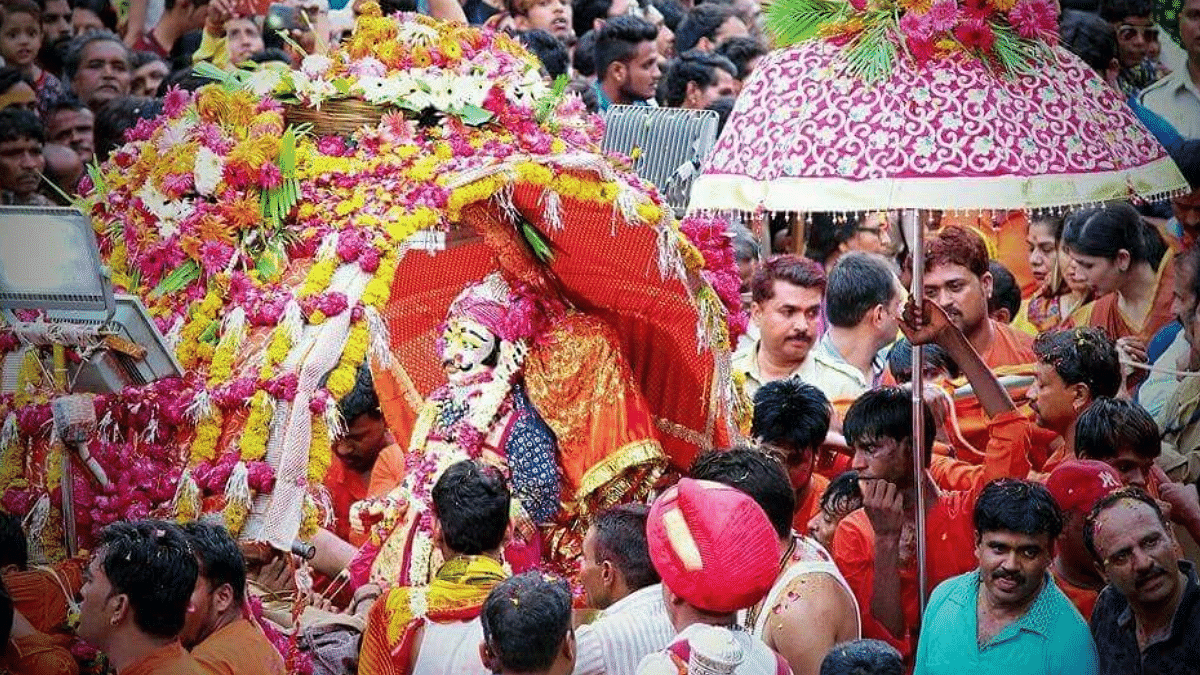

The Lingayats are followers of the 12th-century social reformer, Basavanna, who rejected Brahmin rituals, championed a casteless society with equal opportunities for men and women and no discrimination. But over time, there have been several attempts to subsume Lingayats into the Hindu fold, primarily for political reasons.

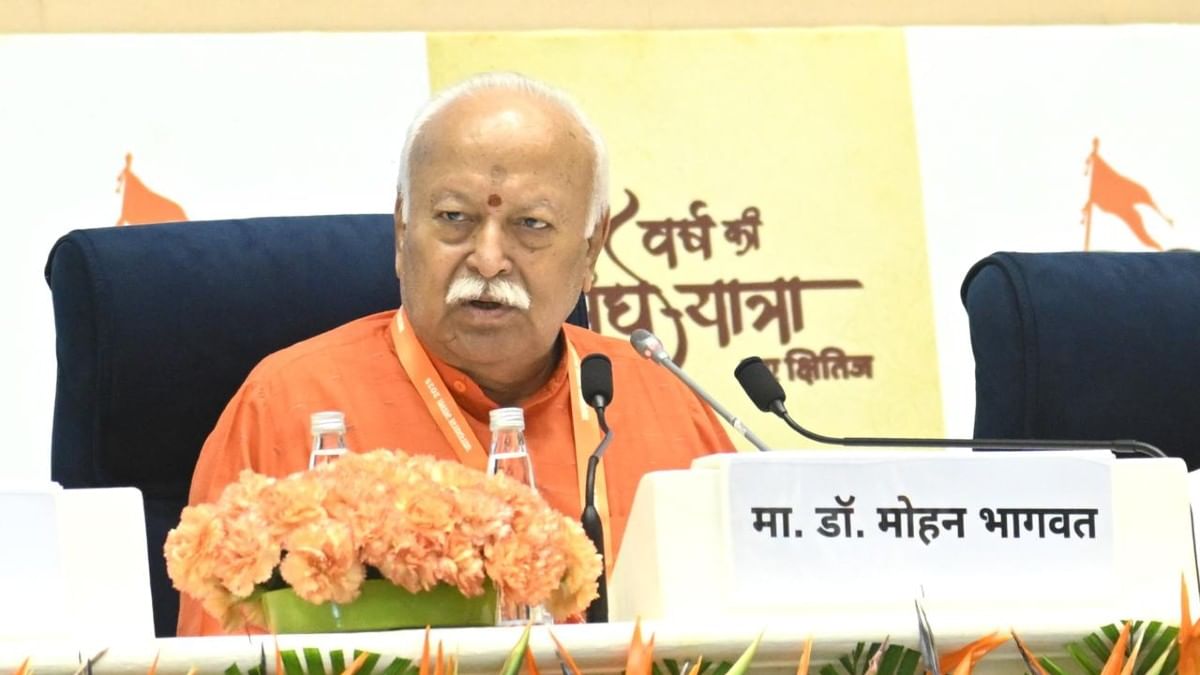

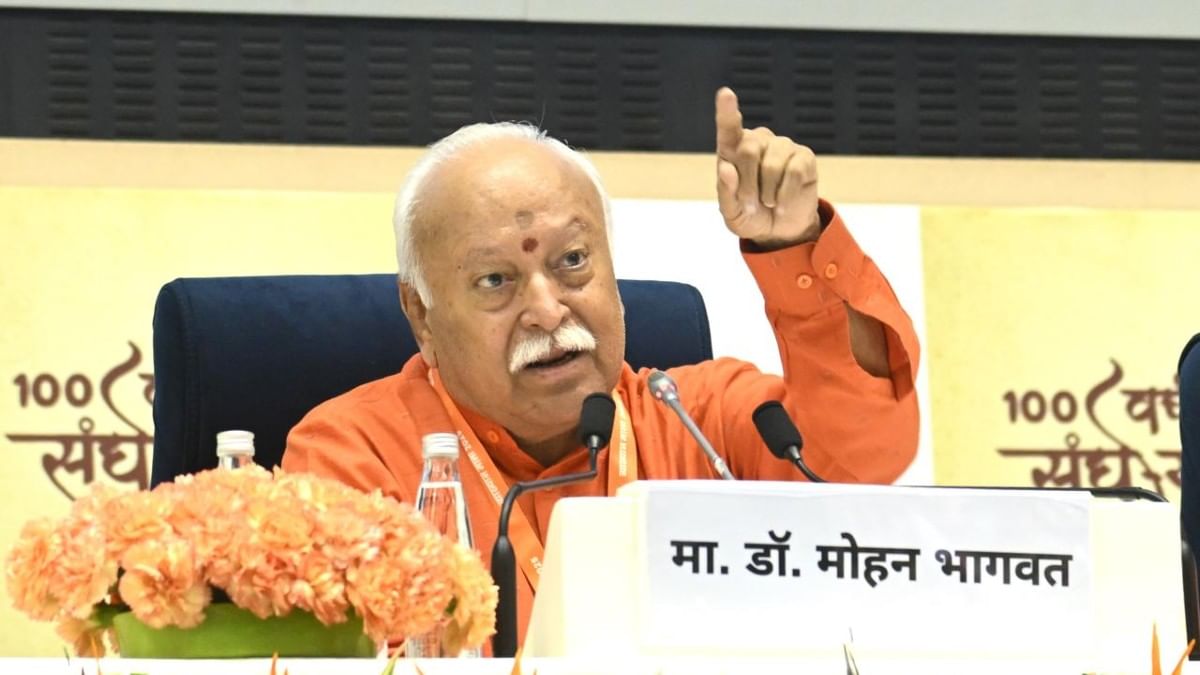

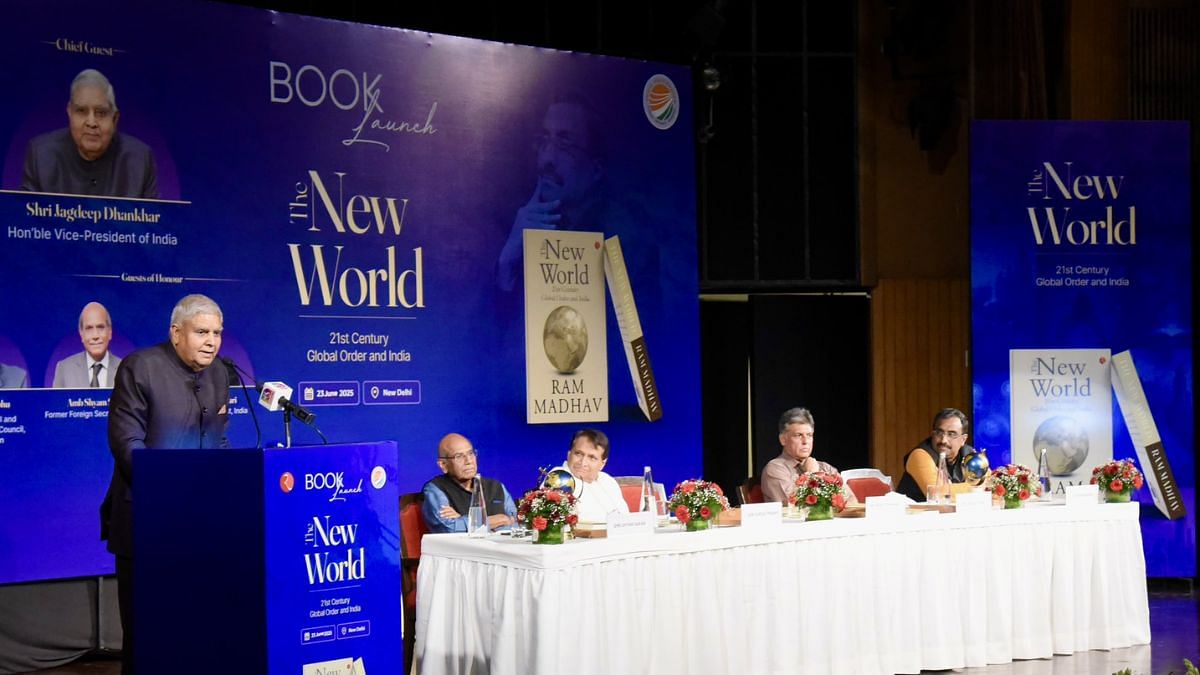

For instance, an RSS-affiliated think tank published a book, Vachana Darshana, which argues that Basavanna’s teachings were “misinterpreted” by Leftist thinkers and Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) fraternity.

The book’s cover image was that of a person meditating and resembling the Hindu deity Ram. This was countered by a 60-page book by scholar Meenakshi Bali, Vachana Nija Darshana (True Teachings of Basavanna), last November, to challenge the assertion.

Although Basavanna propagated for a casteless society, there are over 100 sub-sects within the Lingayats today, with many of them trying to become a force on their own while also remaining under the community’s larger umbrella.

According to one section, Veerashaivas are also a sub-sect of Lingayats and not an interchangeable term with that of the entire community.

Also Read: Who are Lingayats, Veerashaivas, and why they matter in Karnataka polls

Who are the Veerashaivas

Though in some places Veerashaivas and Lingayats are used interchangeably, many insist there are major differences. The larger consensus is that Veerashaivas are more inclined towards Hinduism.

Lingayats trace their origin back to Basavanna, while Veerashaivas are believed to have been born out of Shiva’s lingam. The Lingayats have the Ista lingam and believe Shiva is a formless entity whereas the Veershaiva believe that Shiva is a person from the Vedas.

Lingayats do not believe in Vedic literature and follow the Vachanas, unlike Veersahaivas.

“In the 1801 census under the then Maharaja of Mysore, Lingayats were clubbed with Shudras. Later, the prominent Lingayats wrote to the Maharaja to be classified as Lingi-Brahmins, which is how the association with Hinduism started,” said one Congress leader, requesting anonymity.

The Lingayat population was classified differently under the Madras presidency, Bombay Presidency, Mysore state and Nizam-ruled Hyderabad. This would all get mixed up with the reorganisation of states in 1956.

The word ‘Veerashaiva’ is now completely ingrained with Lingayats, making it harder for political leaders or even prominent seers to discard. In September 2017, Shivakumar Swami of the Siddaganga Matha, one of the most revered religious leaders, said in a statement that the words Veerashaiva and Lingayats are the same.

The politics between the sub-sects

Lingayat politics is complicated by the rivalries between different sub-castes.

The Lingayat community is diverse, with prominent sub-sects including Panchamasalis, Ganiga, Jangamma, Banajiga, Reddi Lingayat, Sadars, Nonaba and Goud-Lingayats.

But in many cases, several individual sub-sects are classified differently under the state backward classes list for reservation benefits.

One Bengaluru-based analyst said that Siddaramaiah, who projects himself as the champion of backward classes, has tried to work the sub-castes as separate entities that will shrink the overall numbers of a community. And by extension, bring down their lobbying capabilities.

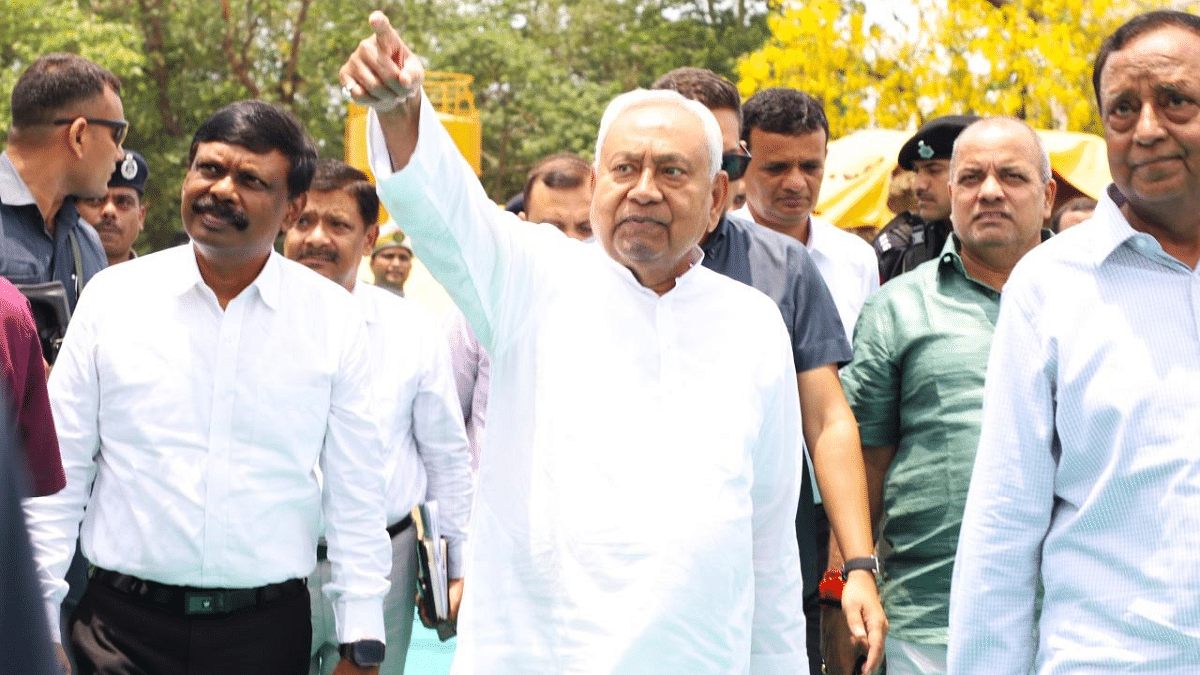

Yediyurappa is considered the tallest leader from this community and has succeeded in getting their backing over the last two decades.

But there is no clarity on his sub-sect as some say he is Banajiga and some say he is Bale-Banajiga, or people earlier involved in the business of Bangles. Former chief minister Basavaraj Bommai and Shivashankarappa are Sadr-Lingayats, a proportionally smaller sub-sect within the community.

The Banajigas have probably the highest share of chief ministers in the state as S. Nijalingappa, J.H. Patel, Veerendra Patil, Jagadish Shettar and S.R. Kanti are from this sub-sect.

But other sub-sects too have claimed ownership of some of these leaders. These are among the reasons why the Panchamasalis, the biggest among the Lingayats, continue to demand that a leader from this group be considered for the top post.

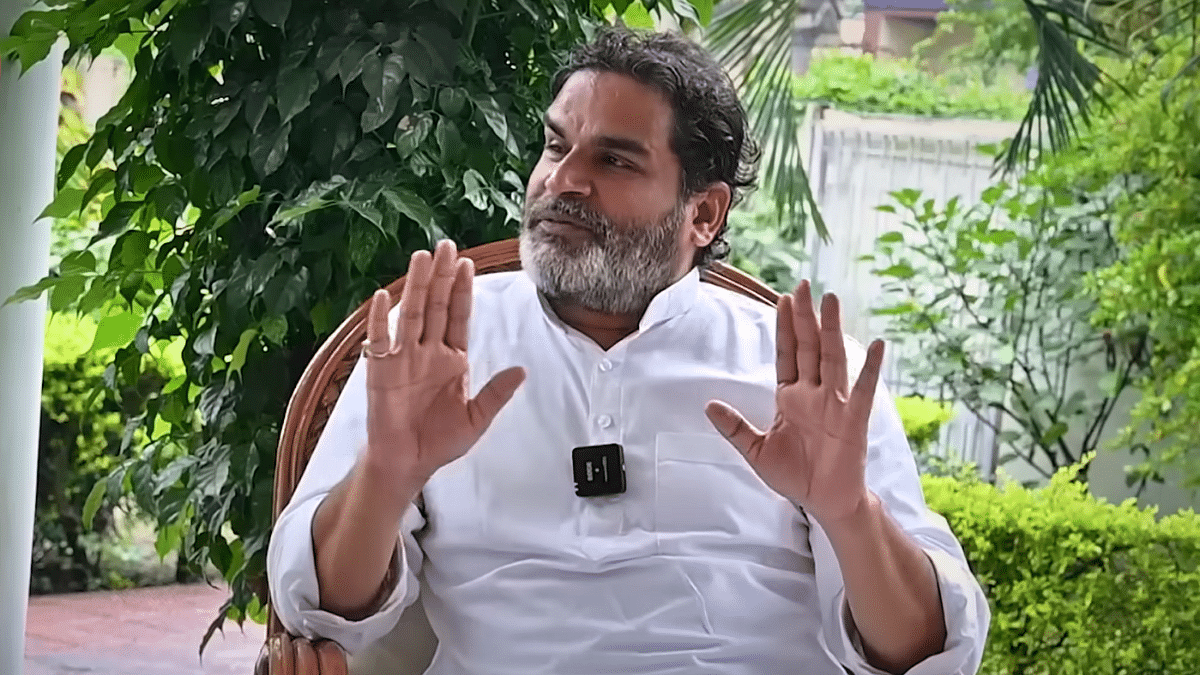

Basanagouda Patil Yatnal, the firebrand leader who was expelled from the BJP, Deputy leader of the opposition Arvind Bellad, cabinet minister Lakshmi Hebbalkar are the prominent members of this group.

(Edited by Sugita Katyal)

Also Read: How Karnataka’s medieval Lingayats challenged caste, oppression of women & toppled empires