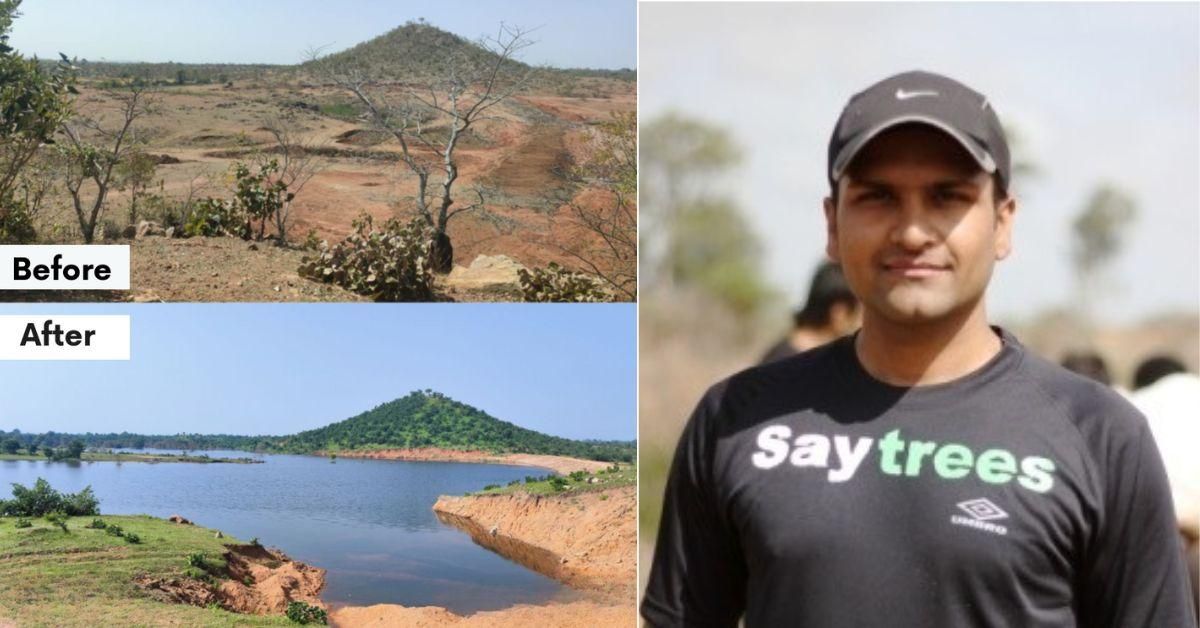

In 2017, while on a casual trip to Bellary in Karnataka, Dr Jogesh Choudhary found himself walking through vast stretches of sandalwood plantations. The air carried a faint woody fragrance, and the sight of thousands of trees left him wide-eyed.

It reminded him of childhood tales, of sandalwood’s allure, the smuggling stories, and its rarity. “I had only heard stories of sandalwood being smuggled. Seeing it grow in such large numbers was surreal,” he recalls.

That moment lingered long after he returned to his village, Bheemda in Barmer district of Rajasthan.

A senior medical officer by profession, Jogesh couldn’t shake off the image of those trees standing tall under the southern sun. A year later, during another trip to Gujarat, he met farmers successfully cultivating sandalwood.

An idea sparked: why not try it in the desert?

“If sandalwood could thrive in Karnataka and Gujarat, could it not also take root in the desert sands of western Rajasthan?” he questioned himself.

/filters:format(webp)/english-betterindia/media/media_files/2025/09/15/sandalwood-2025-09-15-14-34-07.jpg)

Little did he know that this question would soon build his relationship with farming forever.

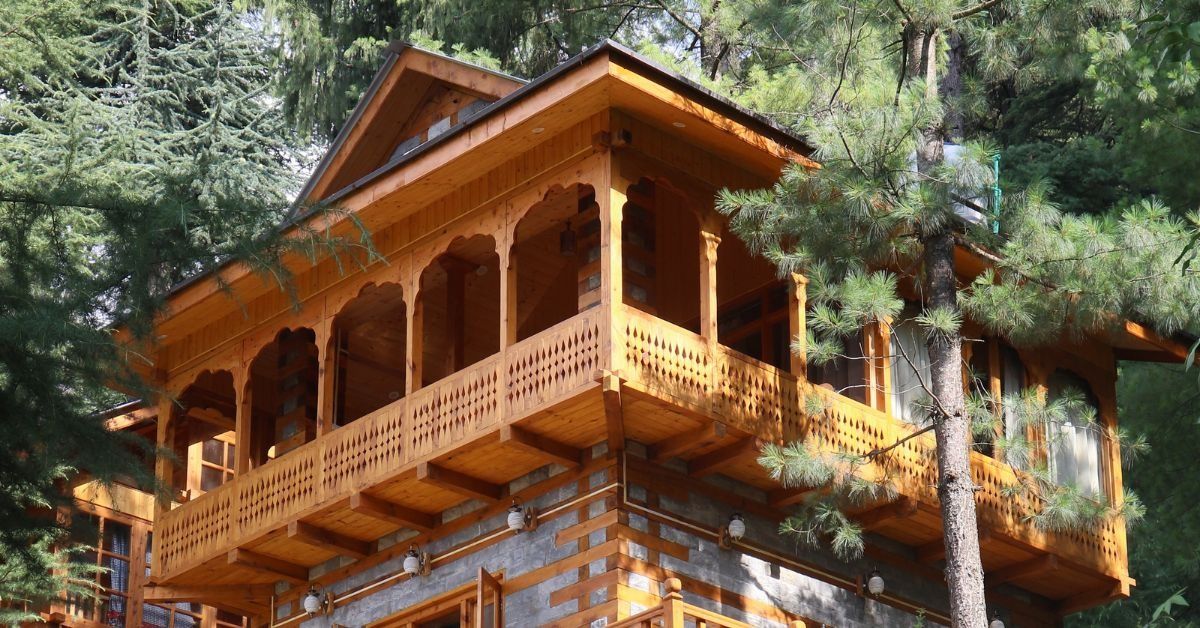

Today, at his village in Barmer, where temperatures soar past 45°C and rainfall is a rare blessing, rows of young sandalwood saplings sway gently, sheltered by guava, pomegranate, amla, and neem.

The first attempt: A bitter loss

In 2021, Dr Jogesh planted 900 sandalwood saplings on his ancestral land. After gaining knowledge from local farmers and researching on his own, he believed the hardy desert soil would adapt to the trees.

Within two months, a disaster struck.

“When I uprooted the plants, I found termite infestation. Termites silently invaded the young roots, and one by one, every sapling withered. Once they attack sandalwood, it’s almost impossible to save them,” shares Dr Jogesh.

“All 900 plants had died. I lost Rs 1.3 lakhs,” he recalls in disappointment.

His family, already doubtful of his unusual experiment, questioned his decision further. Why would a practising doctor, with a stable career, risk his money and reputation in an uncertain crop?

The second attempt

Jogesh, however, wasn’t ready to surrender. “If I had failed another time, I would have stopped. But I didn’t want to give up after just one try,” he says.

Determined, he dived deep into research. He reached out to scientists at the Arid Forest Research Institute (AFRI), read research papers by its director, and absorbed every detail he could find online. “YouTube became my teacher,” he laughs.

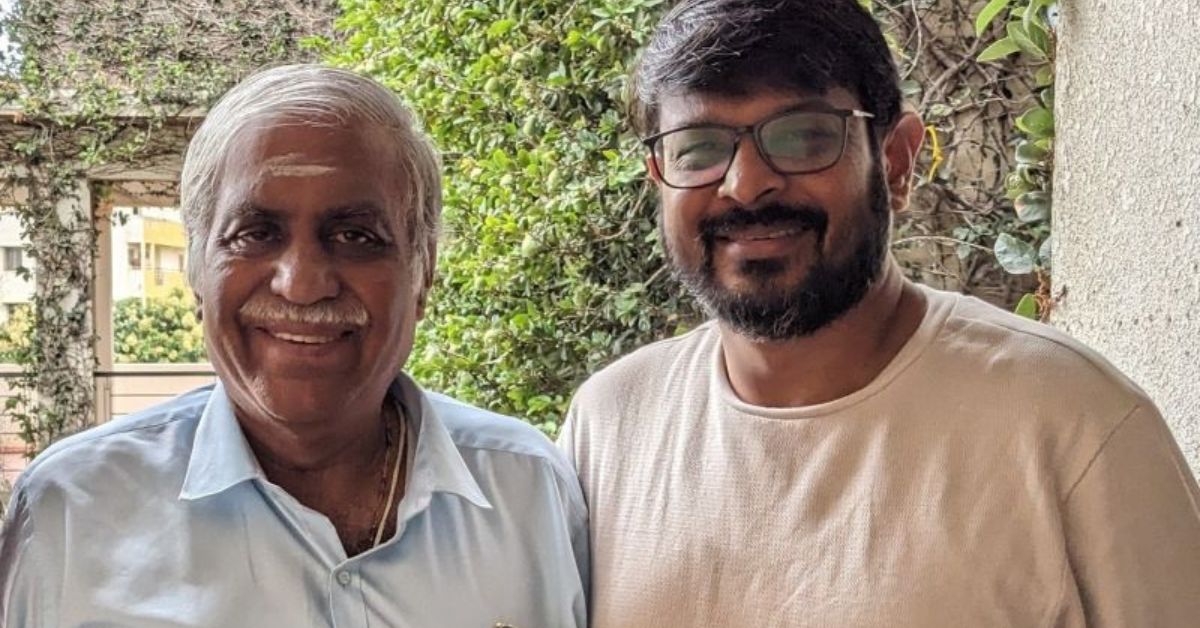

But can sandalwood truly be grown sustainably in Rajasthan’s desert regions? To answer this, we reached out to the director of AFRI, TS Rathore, who has spent years studying the crop.

“Yes, it is possible,” he affirms. “My research and practical work have shown me that sandalwood can grow in Rajasthan, but only under certain circumstances and conditions. Scientific planning makes the difference between success and failure.”

Rathore’s expertise comes from over 14 years of working on sandalwood farming in Bengaluru, after which he moved to Jodhpur to continue his research in the state’s tougher terrain.

/filters:format(webp)/english-betterindia/media/media_files/2025/09/15/sandalwood-1-2025-09-15-14-34-07.jpg)

Explaining the challenges, he says, “In natural habitats, sandalwood requires around 800 mm of rainfall. Rajasthan’s arid zones often receive less than 400 mm, which makes irrigation essential. With proper irrigation during both summer and winter, sandalwood can survive even in areas with 400 mm rainfall, sometimes even 300 mm. But below 200 mm, with extreme heat and water loss, survival becomes very difficult.”

So, what makes sandalwood farming sustainable in such a harsh climate? Rathore points to scientific management as the key.

“The first step is creating shelterbelts to block hot winds, then planting sandalwood in blocks, and ensuring drip irrigation. If these are managed well, sandalwood can definitely be cultivated in Rajasthan,” he adds.

A forest in the desert

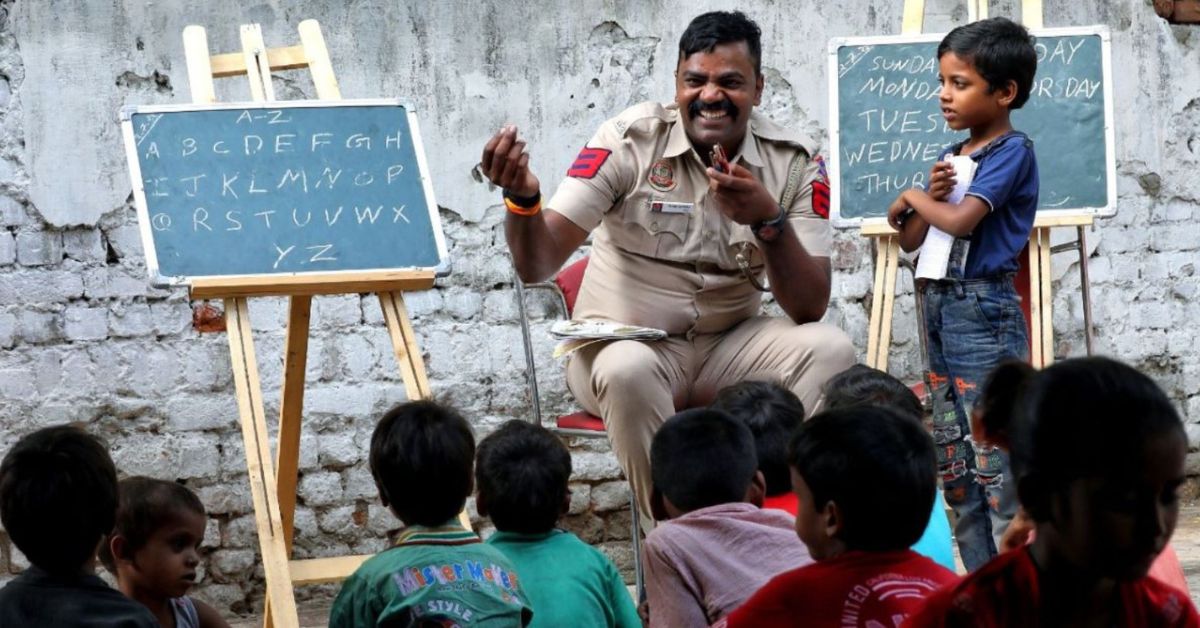

By 2022, Jogesh returned to the land with renewed confidence. This time, he treated every sapling against termites and adopted a strict monthly treatment routine. Slowly, green shoots replaced the barren soil.

Today, Jogesh’s 20 bigha farm resembles a small forest. Around 900 sandalwood trees share space with 6,000 fruit and timber trees, guava, lemon, amla, pomegranate, figs, teak, and Malabar neem.

Unlike other trees, sandalwood is a semi-root parasite. It requires host plants to draw nutrients. Without these, sandalwood will not develop well.

Hence, here are the three pillars of a successful sandalwood cultivation:

/filters:format(webp)/english-betterindia/media/media_files/2025/09/15/sandalwood-2-2025-09-15-14-34-07.jpg)

Since sandalwood needs host plants, Jogesh carefully intercropped it with Casuarina trees and fruit trees. He also planted fast-growing “wind breakers” like Malabar neem, which shoot up to 25 feet in two years, shielding delicate sandalwood from scorching winds and cold waves.

He also relies on drip irrigation and a permaculture approach. “Fallen leaves fertilise the soil naturally, and in the early years, I used only cow dung. I don’t use chemical fertilisers. The farm is designed like a forest, and it sustains itself,” he says.

The patience of a farmer, the precision of a doctor

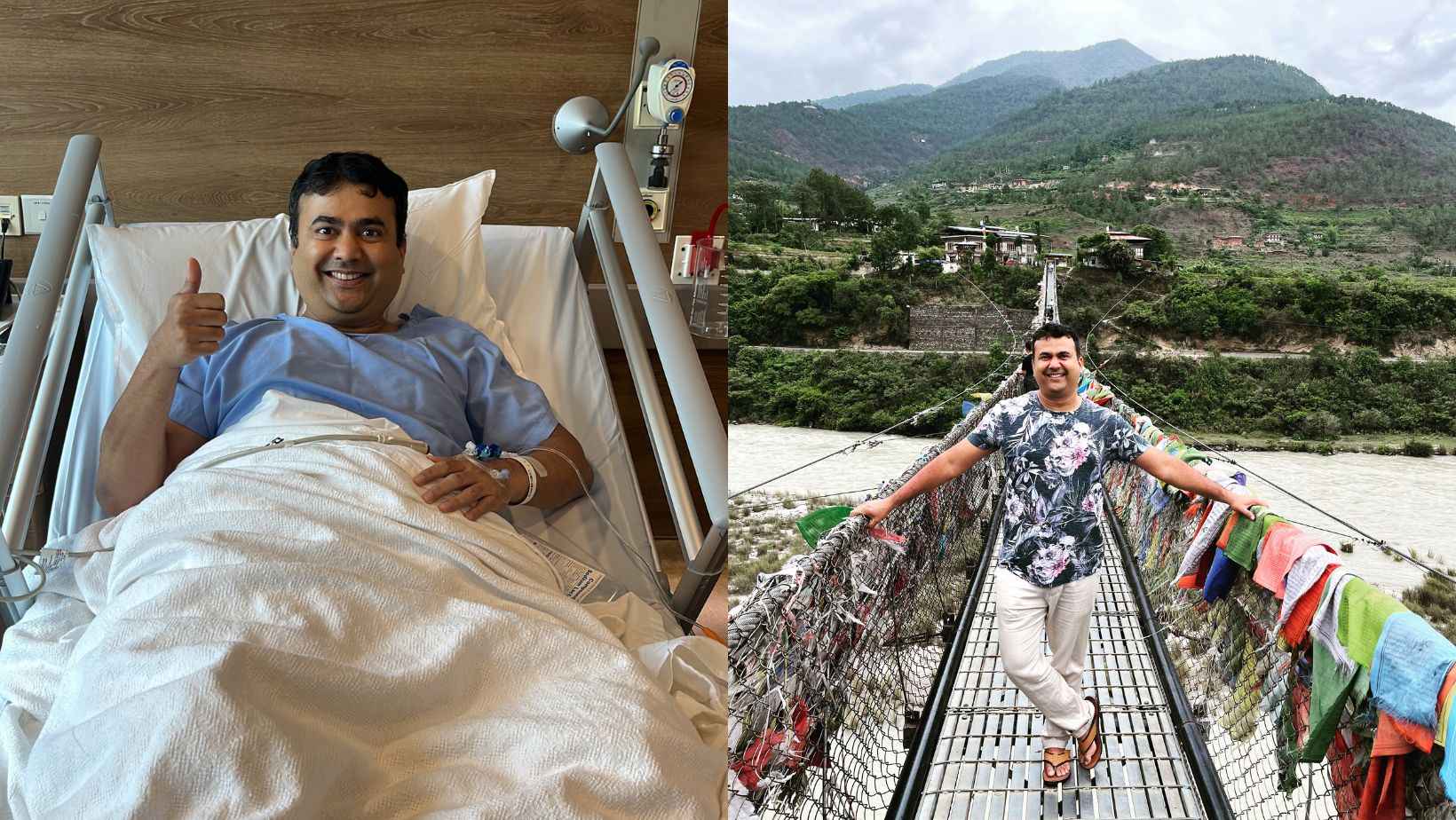

Jogesh’s sandalwood trees now stand 8–10 feet tall. They will take another decade to mature, but he isn’t anxious. “It’s like raising a child. The first two years needed utmost care, and then they grow on their own,” he adds.

The crop has already cost him around Rs five lakhs. “I incurred major costs in installing a drip irrigation set-up, and a large part of the cost was covered through government support. Out of the total 610 irrigation units, I installed 230 myself, and the remaining 380 were provided through subsidy,” explains Jogesh.

He informs that in terms of maintenance, sandalwood doesn’t demand heavy recurring costs, but proper soil health management is crucial.

“One has to understand the balance of nitrogen, potassium, and other nutrients to keep the plantation healthy. Fertilisers and soil care form the main part of ongoing expenses. I do not add anything externally, as dry leaves falling on the ground are sufficient to provide nutrients to the plants. Now, all they need is water,” he smiles.

If things go well, each tree, Dr Jogesh says, could yield Rs 2–4 lakhs. But he insists money isn’t his focus. “I feel happy just noticing a new leaf. Walking through my farm takes care of my mental health. I am not doing this for monetary gains,” he adds.

/filters:format(webp)/english-betterindia/media/media_files/2025/09/15/sandalwood-4-2025-09-15-14-36-20.jpg)

Sandalwood is a protected species under Indian law. While individuals can legally cultivate it on private land without prior permission, the government regulates its harvesting, transit, and marketing. As stated, in the Forest Areas Act, 2005, the wood is auctioned by the state, and profits are then shared with the cultivators.

“Farmers need to apply for clearance before felling or marketing sandalwood. This is mainly to prevent smuggling and ensure proper monitoring. But ownership remains with the grower,” says Dr Jogesh.

Lessons for other farmers

Jogesh believes sandalwood farming isn’t for everyone. “It requires patience, of 12–15 years. Routine farmers who depend solely on it may struggle. That’s why I suggest planting sandalwood as an intercrop along with income-generating crops,” he says.

His advice is simple yet hard-earned:

-

Maintain a minimum spacing of 15 feet row-to-row and 12 feet plant-to-plant.

-

Choose native host plants for better survival.

-

Protect against termites with regular treatment.

-

Think long-term and don’t chase sandalwood just for quick profits.

Commenting on whether sandalwood farming is feasible for small and medium farmers from an economic standpoint, TS Rathore says, “Sandalwood can be rewarding only if managed properly. Hardwood formation in sandalwood starts under stress, and Rajasthan’s climate of extreme heat and cold naturally provides that stress, which is good for quality. The oil percentage in young trees (15–20 years) may be two to three percent. As the tree matures, both oil content and quality improve.”

“Market value depends on two things: the percentage of oil and the amount of heartwood. If the oil content is two percent, prices may be Rs 7,000–8,000 per kg, but if it rises to four to five percent, prices can jump to Rs 12,000. So with good host plants, proper spacing, and termite management, returns can be very attractive in the long run,” he adds.

A hobby that became a forest

For a man whose profession revolves around saving lives inside hospital walls, tending to trees in a desert farm may seem unusual. But Jogesh sees no contradiction.

“My grandfather grew bajra, moong, and pulses here. I am using the same land, but differently. I thought of sandalwood as a long-term project, a retirement crop,” says the 37-year-old.

“It takes 12–15 years to mature, but I am not doing it for quick money. It is more like a hobby, an experiment, about growth and patience. This farm gives me peace after a long day at work. So, even if I don’t earn a single rupee, the peace I get here is priceless,” he adds.

Edited by Vidya Gowri; all images courtesy: Dr Jogesh Choudhary.