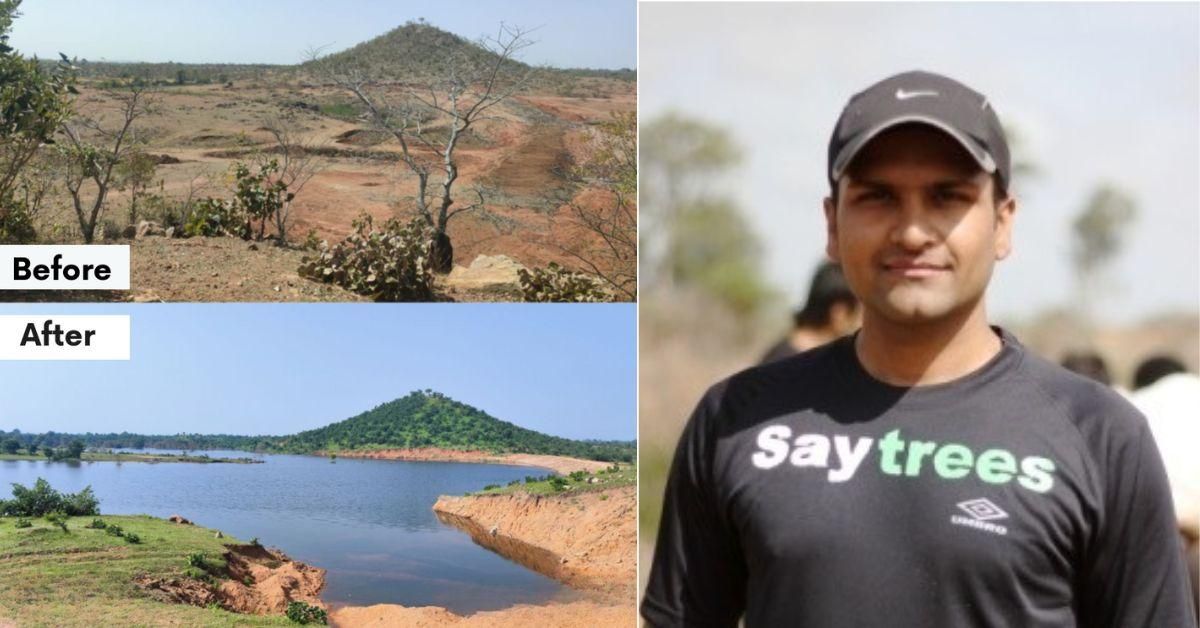

As a child, elephants were farmer Prabhuswamy NC’s favourite animals. But as he grew older, that affection turned into hatred. His fields in Naganapura village, in the Hediyala range of Bandipur National Park, were often ravaged by elephant attacks, and he began associating the animal with crop loss and property damage.

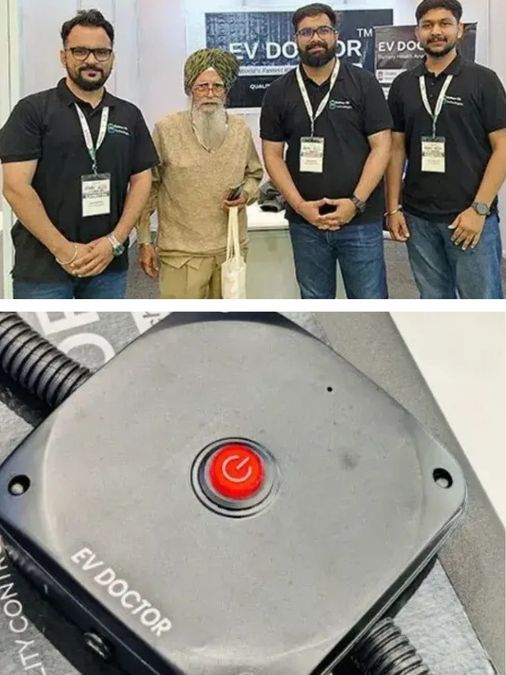

After a decade of battling these crises, a relief programme finally came to his rescue. This was ‘Wild Seve’ — a conservation intervention by the Centre for Wildlife Studies (CWS), an internationally recognised centre of excellence dedicated to safeguarding and conserving India’s rich and diverse wildlife heritage through cutting-edge research, effective conservation strategies, and community engagement.

This programme has spanned 2914 village settlements affected by human-wildlife conflict across Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Kerala.

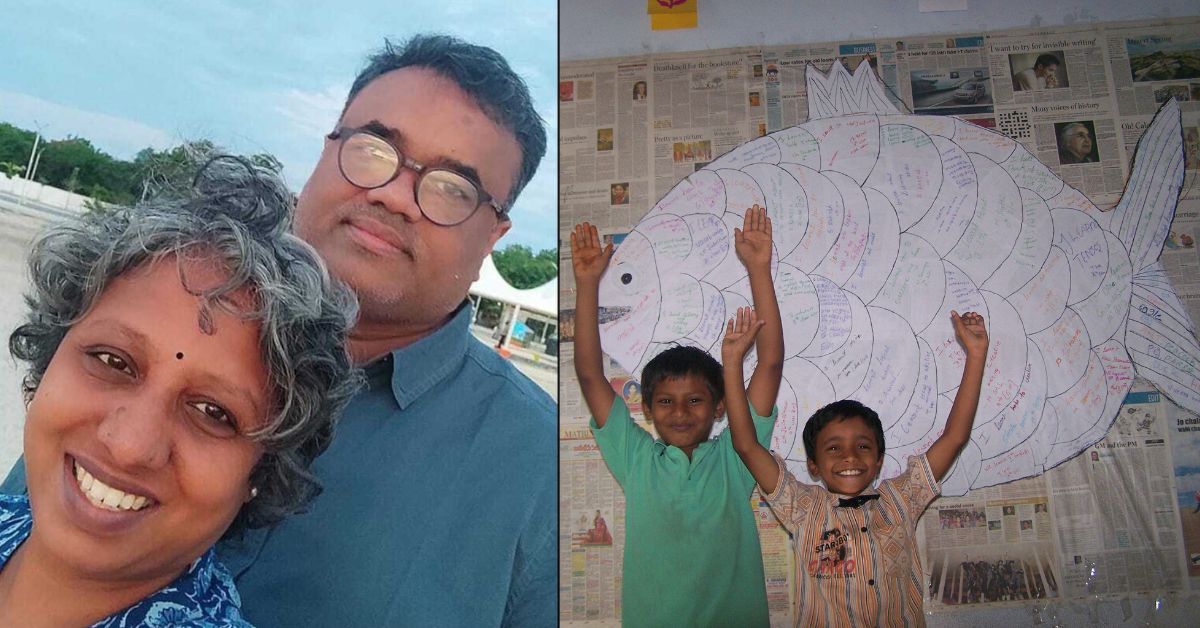

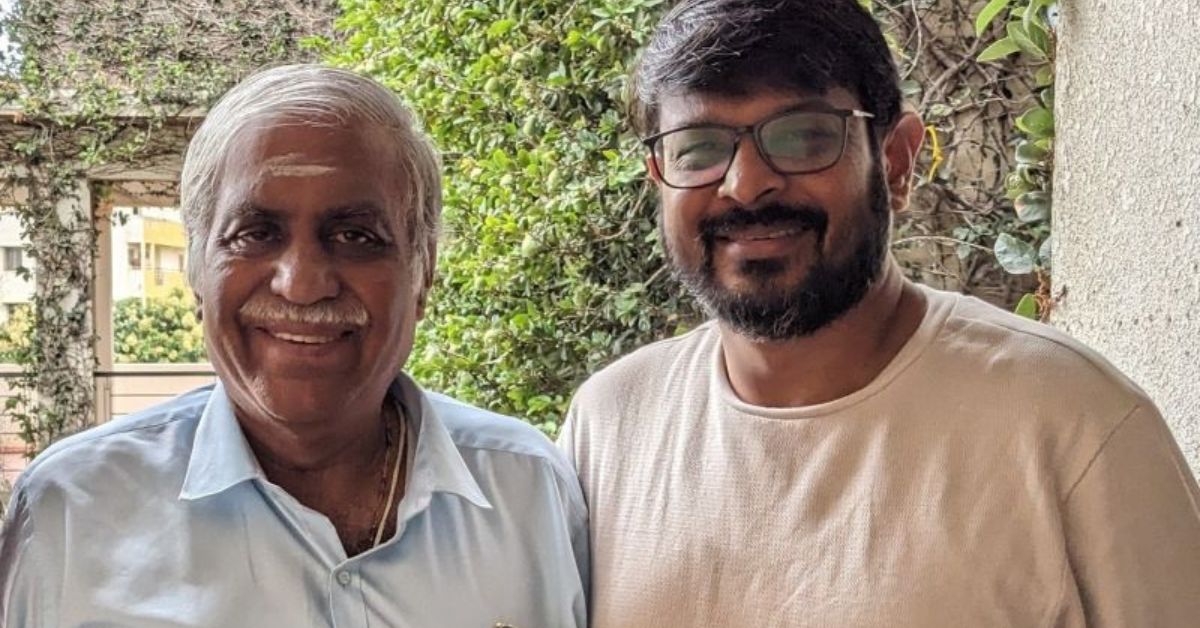

It’s been a boon for farmers like Prabhuswamy, says Krithi Karanth, Chief Executive Officer at the Centre for Wildlife Studies. “Since 2015, we have assisted Prabhuswamy in filing and following up on over 100 cases: 71 for crop damage, 20 for crop and property damage, 12 for property damage, and even one livestock predation case.”

She continues, “Without intervention, each of these incidents would have pushed his family further into financial distress and further into a poverty trap.” The help that the CWS team extended included documenting claims, processing them, and accessing ex gratia from the Government.

But Prabhuswamy’s story isn’t in isolation.

/filters:format(webp)/english-betterindia/media/media_files/2025/09/16/human-wildlife-conflict-1-2025-09-16-15-53-02.jpg)

Photograph: (Representative image)

In forest-fringe villages across the country, communities are at the mercy of predatory hands. What Wild Seve does is act as a bridge between affected families and government mechanisms for compensation. It transforms their despair into resilience, Krithi points out.

For three decades, she’s championed change on the ground, infusing hope and policy shifts into communities dotting the Indian hinterland.

And the recent prestigious McNulty Prize win — the global award recognises breakthrough leaders who effect lasting change by addressing global challenges — lends weight to her efforts. The way Krithi sees it, “The award puts wildlife itself at the centre of the conversation, which is often missing in broader environmental debates.”

The toll of human-wildlife conflict on fringe communities

One story will always be etched into Krithi’s memory. It’s of a 26-year-old Prasanth who lost his father to an elephant attack. “His death left his family shattered and his community in mourning and protest,” Krithi shares. But it wasn’t that Prasanth hated elephants. He was simply exhausted from living a life of uncertainty, not knowing which day would be his last.

Krithi points out that while her team was able to secure Prasanth compensation for his loss, the battle does not end there — “In such conflicts, there are no winners.” In fact, it’s a battle where picking sides isn’t a plausible option.

/filters:format(webp)/english-betterindia/media/media_files/2025/09/16/human-wildlife-conflict-5-2025-09-16-16-05-15.jpg)

On the one hand, Krithi says there are the elephants who are migrating broken paths and fragmented landscapes; on the other there are communities vulnerable and afraid.

Who is right? Who is wrong?

This is where her work attempts to chart the interlinked lives and routines of communities that share ground with the wild. Krithi isn’t the only firm believer in a reciprocal relationship between the two. A report by WWF and the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) acknowledges that while it isn’t possible to completely eradicate human-wildlife conflict, participation of local communities can help reduce it.

From conflict to co-existence: protecting lives and landscapes

In a crowded world, people and wildlife are increasingly competing for space and resources. The encounters between them are more regular – and not all interactions are positive.

The introduction to the UN report underscores a grim reality. And reports concede. Kerala recorded 460 deaths and 4,527 injuries due to human-wildlife conflict in the 2020-2024. Meanwhile, human-elephant conflict in India is estimated at one million hectares of crops lost, 10,000-15,000 damaged properties, and around 400 human deaths, along with around 100 elephant deaths each year.

/filters:format(webp)/english-betterindia/media/media_files/2025/09/16/human-wildlife-conflict-2025-09-16-15-55-00.jpg)

While CWS has been working for the past four decades towards the cause of mitigating human-wildlife conflicts, farmer Prabhuswamy’s story illustrates how deep-rooted the impact of these encounters can be.

“For years, elephants fed on his crops, leaving him without a secure livelihood. The repeated losses pushed him into such despair and anger that, at one point, he resorted to electrocuting an elephant, an act that still haunts me,” Krithi shares, adding, “It shows just how fragile coexistence can be when people are left alone to shoulder the costs of conservation.”

Nagachandan Honnur, who started his career at CWS as a field assistant and is now senior programme manager of the Wild Seve programme, has closely interacted with farmer Prabhuswamy. He shares, “Farmers like Prabhuswamy have a love-hate relationship with the animals. They try to co-exist, but when they lose something, they grieve, they shout.”

Reasoning why the loss warrants this reaction, Nagachandan says, “Only 30 percent of the farmers in these villages have an irrigation facility, the rest don’t; and so grow rain-dependent crops, which are three-month crops. But they can’t expect much profit from these. So, when these crops are destroyed, the losses affect them.”

But, now, the ex gratia compensation (Rs 2,00,000 a year) provides Prabhuswamy a safety net. He acknowledges this: “Now, I don’t harm any animals, because I get proper support.”

This sentiment is mirrored by Nooralaiah, a farmer in the Sargur range of Bandipur National Park. Nooralaiah isn’t proud of his past. He’s spent many a night on makeshift watchtowers, throwing stones at deer. But after the sessions by Wild Seve, he resorts to the formal route and calls for assistance when his fields are threatened.

/filters:format(webp)/english-betterindia/media/media_files/2025/09/16/human-wildlife-conflict-2-2025-09-16-15-58-16.jpg)

These stories aren’t hearsay.

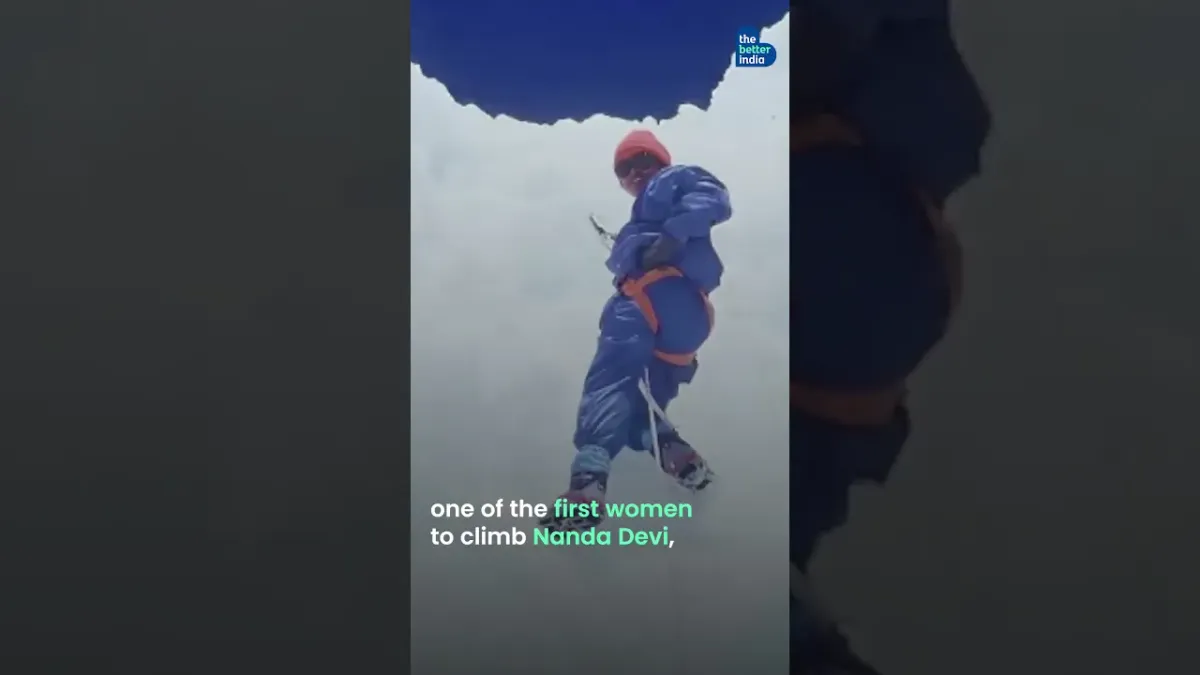

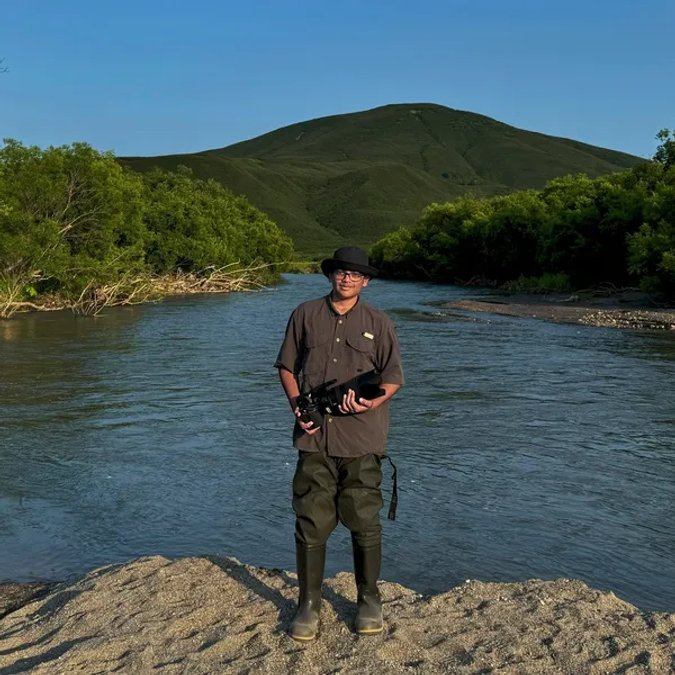

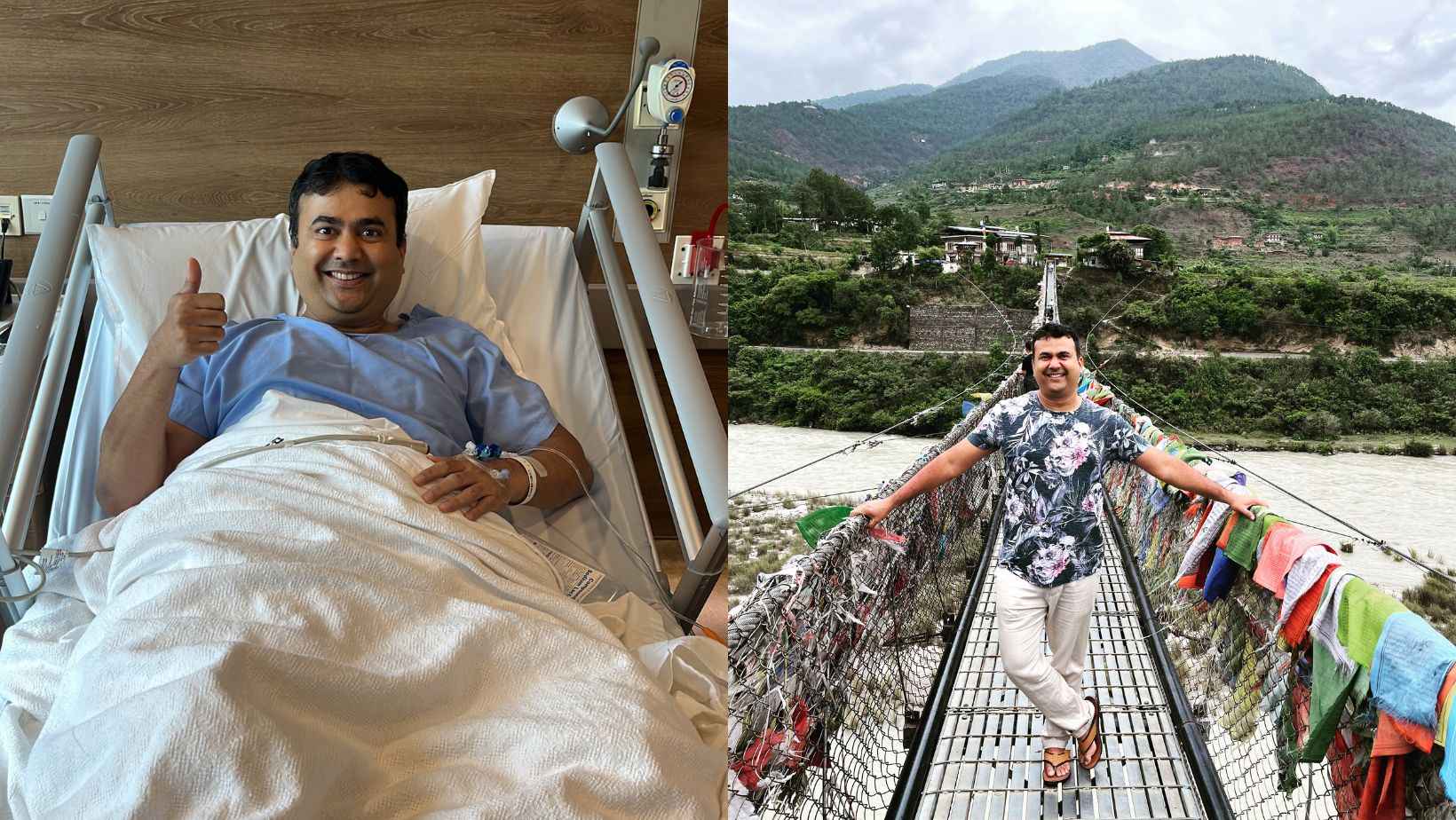

Krithi’s chequered career — while in a full-time role at CWS, she also lectures at Duke University, North Carolina, and is on the National Geographic Education Audit Advisory Board, among other roles — has given her a front row seat to the challenges that communities living in proximity to wildlife corridors grapple with.

And the McNulty Prize is the latest addition to a list of accolades, including the MDPI World Sustainability Award (2023), the Eisenhower Fellowship (2020).

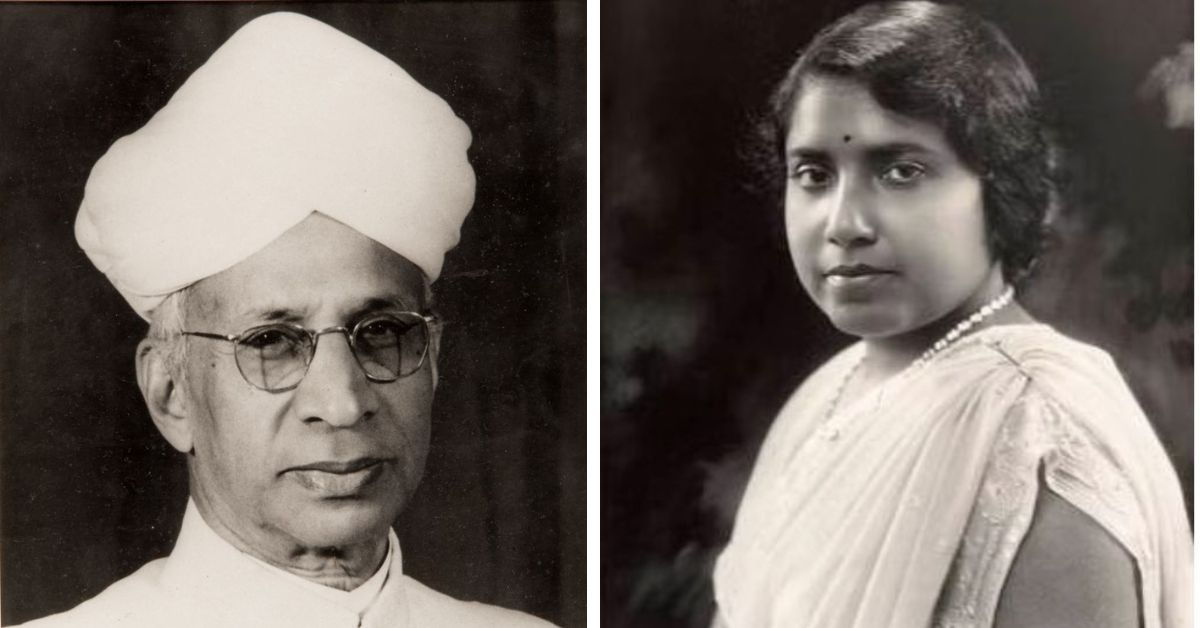

But, she isn’t one to rest on laurels. The way Krithi perceives the journey of the past three decades is a result of intuitive effort. Her acumen for this work was inspired by her parents. “I was fortunate to grow up in a family where both my parents were scientists, and nature was part of our everyday lives. My father, being a tiger biologist and conservationist, often took me along on his fieldwork. I saw my first tiger when I was just two years old.”

Tales of animals colour most of her childhood memories. “At the time, I did not fully grasp what an extraordinary gift that exposure was; it just felt natural to me. However, looking back, those early experiences of observing wildlife so closely left a deep imprint on me.” This glimpse into her upbringing is a nod to why she’s so passionate about wildlife and its protection.

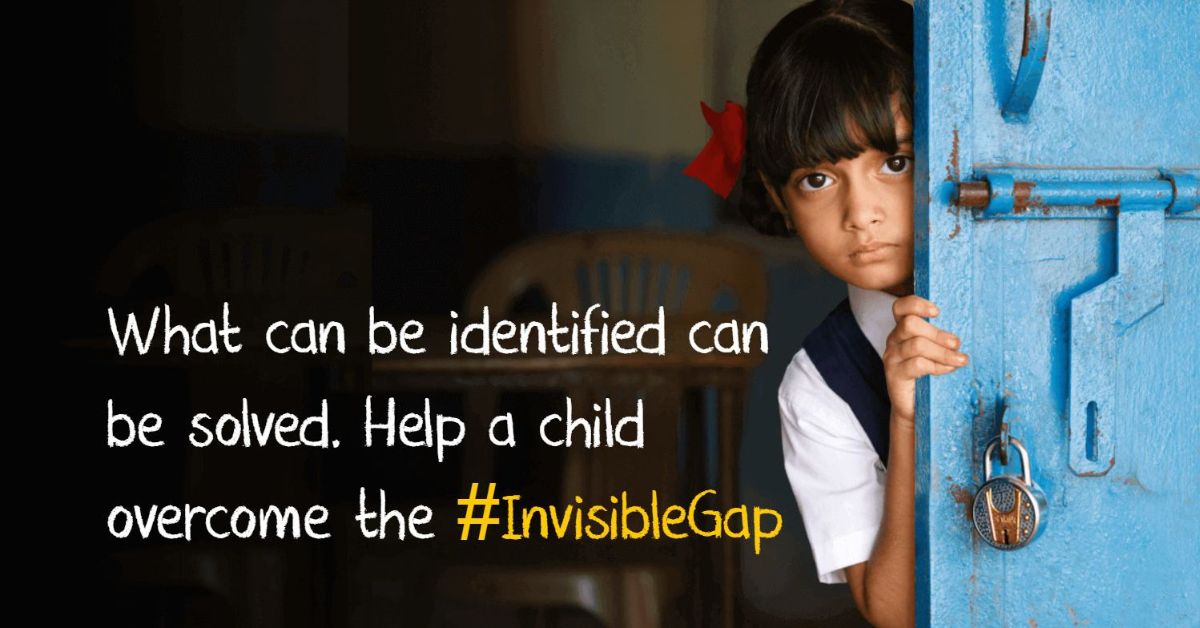

Helping children navigate the perils of human-wildlife conflict

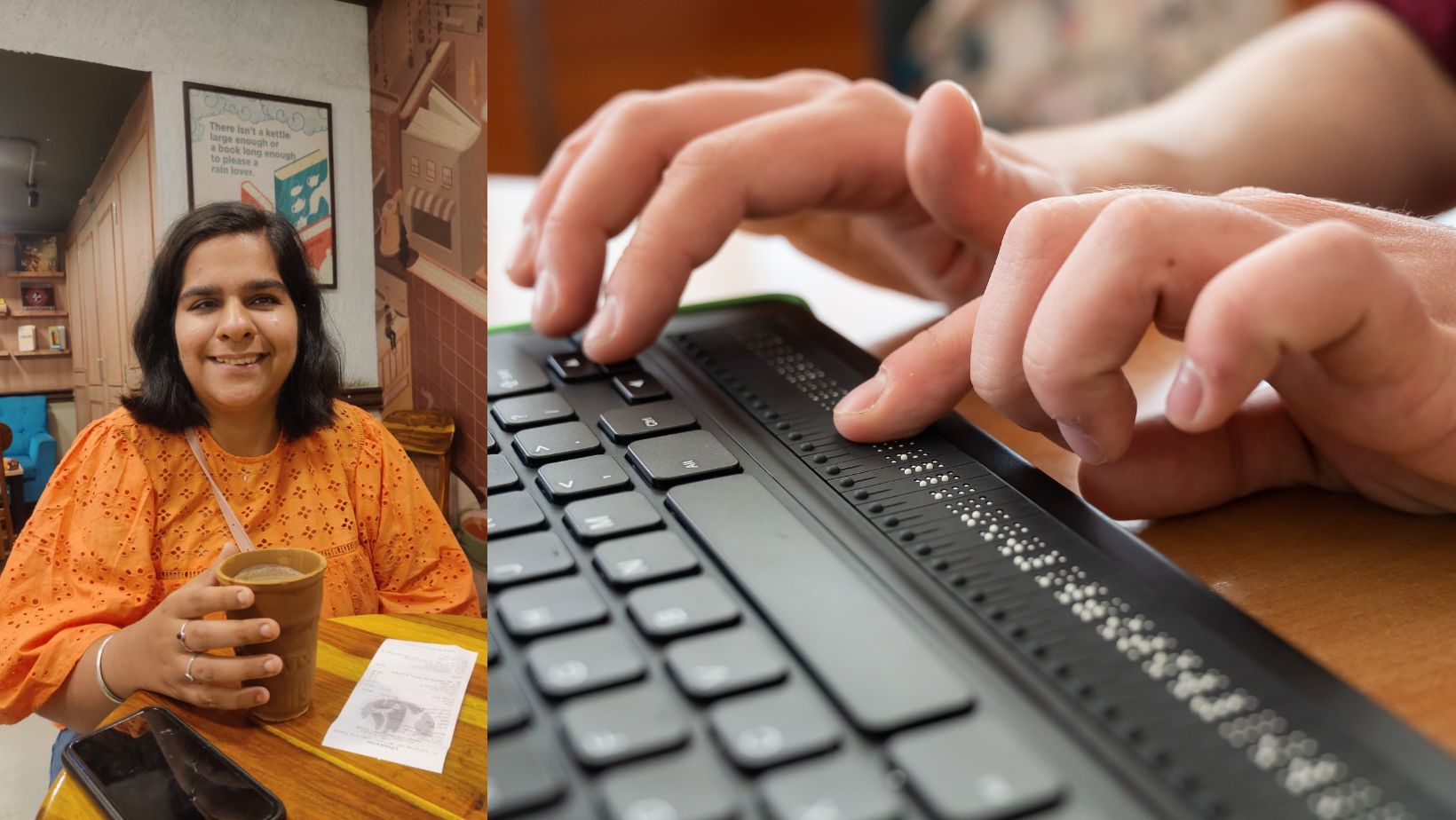

Arun (11) still recalls the night a jackal tried to snatch his family’s hens. For years, the memory kept him awake.

In an article for Mongabay, psychiatrist Jaya Navani acknowledges that human-wildlife conflict can leave a lasting imprint on a child’s psyche, even causing Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). These children, she says, may repeatedly relive the traumatic event and avoid places where they fear encountering animals.

/filters:format(webp)/english-betterindia/media/media_files/2025/09/16/human-wildlife-conflict-3-2025-09-16-16-00-51.jpg)

Even beyond a psychological impact, the effects of the animals destroying the farmers’ crops spill into the children’s lives. As Nagachandan shares, “I recall one of the farmers whom I had spoken to, and was helping access ex gratia compensation, sharing that he usually earned Rs 2,00,000 through the crops that he grew.”

But that particular year, peacocks, pigs, and spotted deer had ventured into his fields, destroying the crops and the farmer’s potential earnings. “He was looking forward to the money that he would earn through the crops so he could pay the fees for his daughter’s studies. This loss meant he would have to compromise on her education. She would too.”

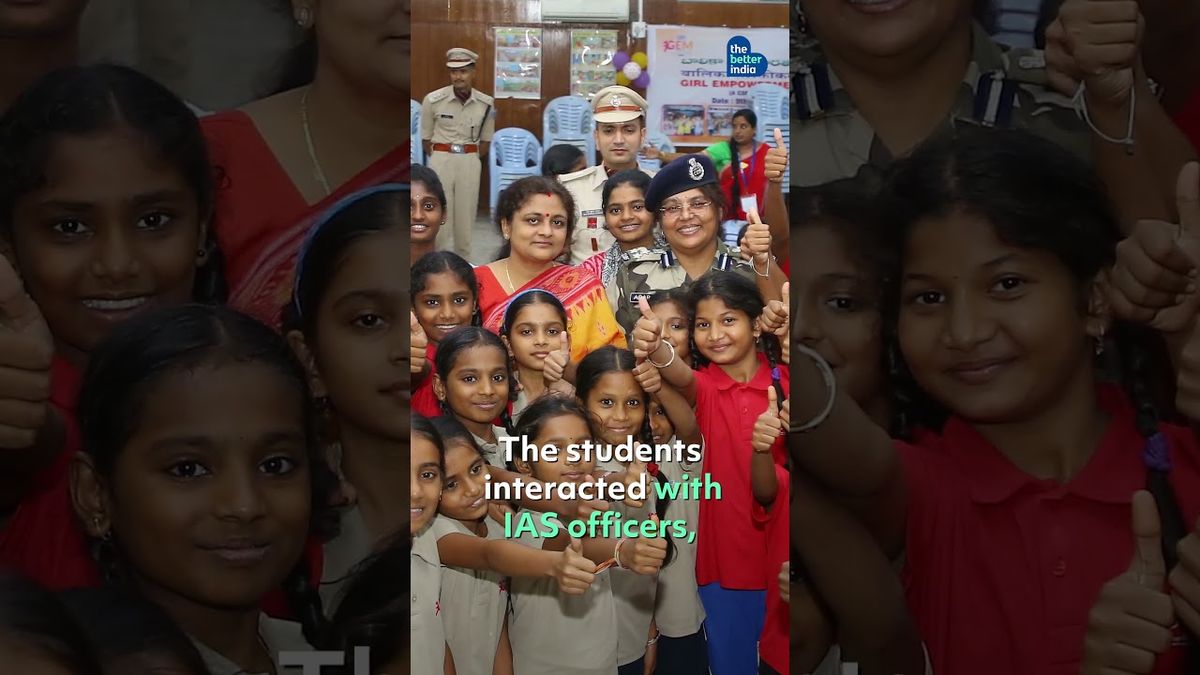

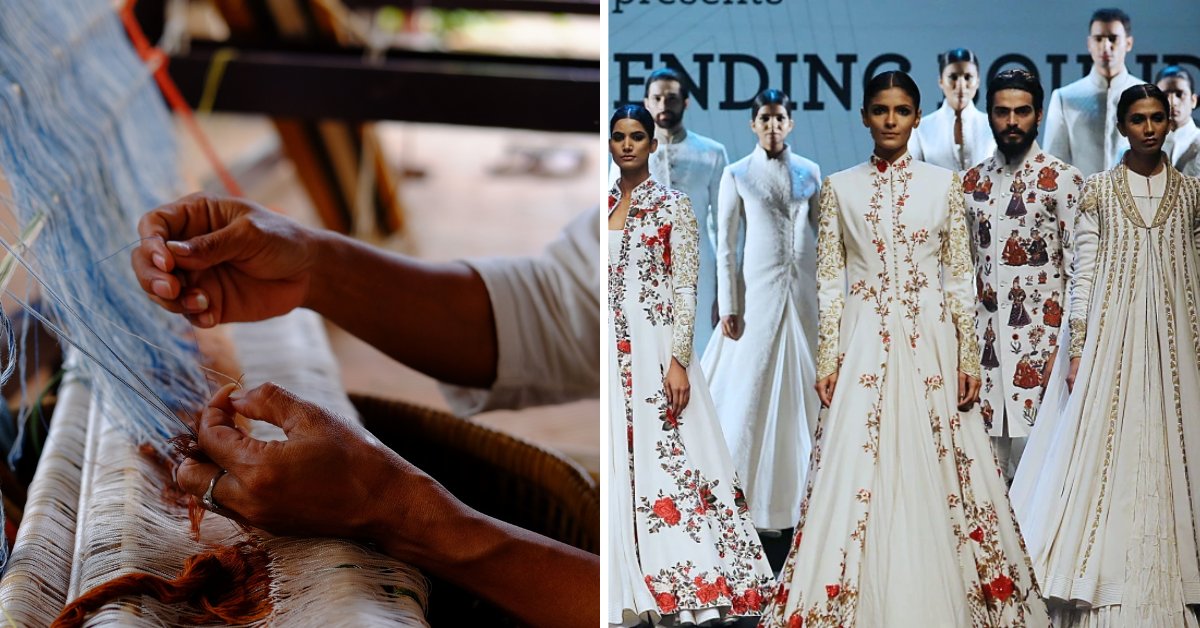

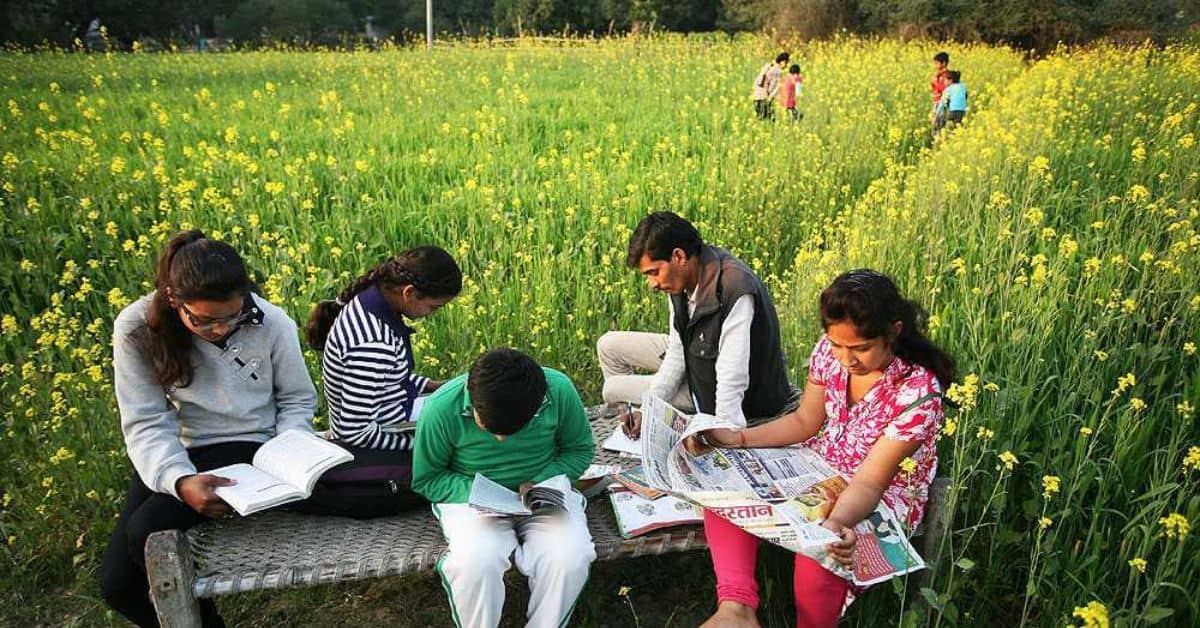

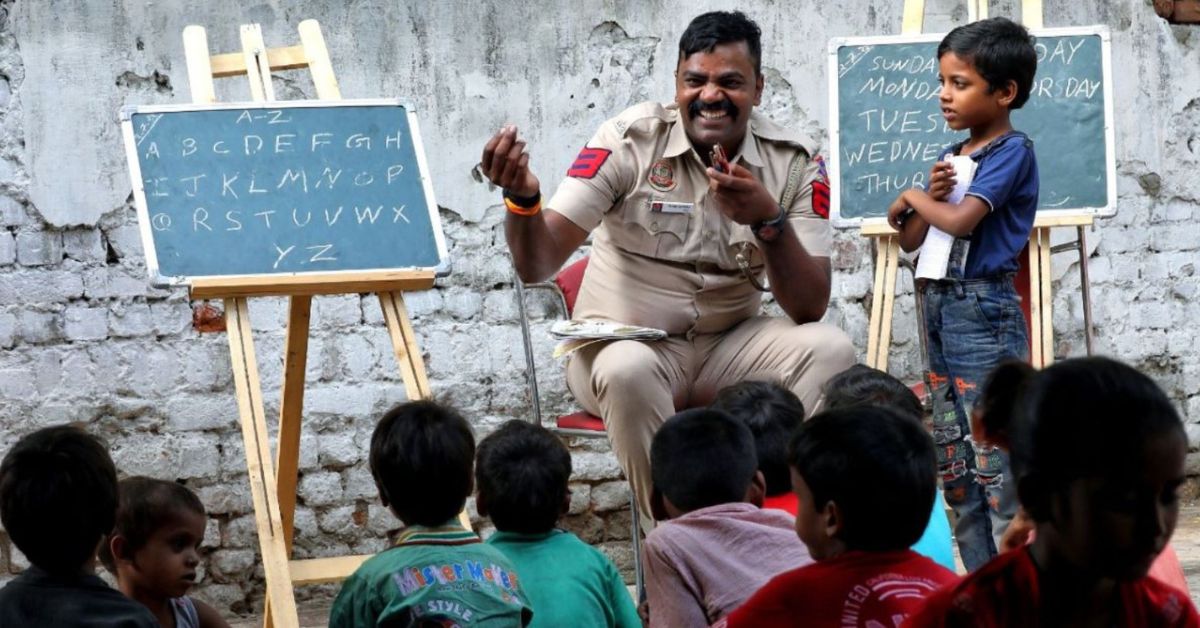

And this is what CWS’s ‘Wild Shaale’ sessions want to address. Through the sessions, children are encouraged to process their experiences and see the wild as part of a larger story of coexistence.

Krithi explains, “Wild Shaale was launched to equip children in forest-fringe communities with the knowledge and empathy needed to understand local wildlife and navigate the challenges of growing up amid human–wildlife conflict.”

Through engaging, activity-based lessons delivered in multiple languages, the programme has reached over 56,000 children across 1,400 schools.

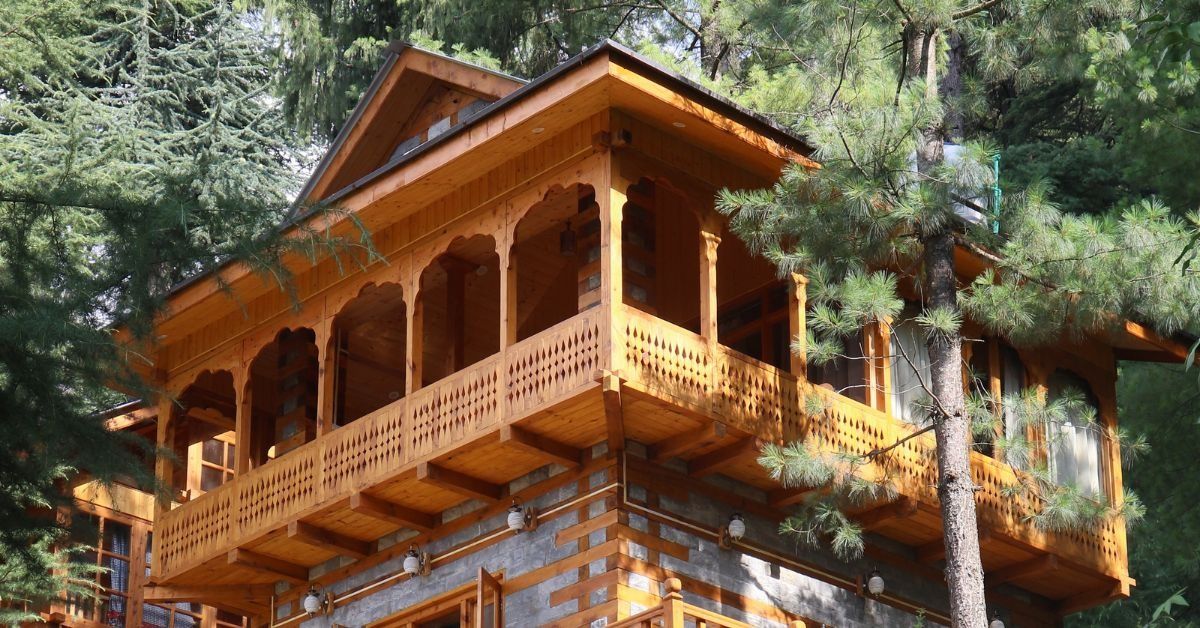

Then there’s the ‘Wild Incubator’ programme, which invites proposals from organisations; the top five receive seed funding to pilot their ideas on the ground. They encourage projects that focus on human-wildlife interactions, combat wildlife trade and illegal hunting, promote biodiversity conservation and focus on restoration and rewilding.

/filters:format(webp)/english-betterindia/media/media_files/2025/09/16/human-wildlife-conflict-4-2025-09-16-16-02-44.jpg)

But the way Krithi sees it, intent needs to cut through the noise. “Laws and patrols can only go so far if communities do not value the wildlife around them. Conservation efforts succeed when people see the importance of protecting species, whether through education, awareness, or their own lived experiences. In my view, it is this alignment, between field action, political will, and public support, that has created the most encouraging examples of wildlife recovery.”

To this end, the McNulty Award, she believes will “open up exciting opportunities” encouraging them to be “bolder in embracing innovation”. She shares, “If we are to secure a future where people and wildlife both thrive, we must act with urgency, compassion, and foresight.”

Edited by Pranita Bhat, All pictures courtesy CWS