The drive down the double-lane Damar road from Punjab’s Ferozepur city to Khai Pheme Ki village takes 15 minutes. Flanking the road are freshly harvested fields and trucks loaded with grain-filled sacks. Farm houses appear intermittently. On the face of it, the regular cycle of sowing and reaping continues in this village in Ferozepur district, in the State that feeds the Food Corporation of India with the largest share of wheat.

Khai Pheme Ki village sits less than 15 kilometres away from India’s border with Pakistan. On a scorching day in May, hundreds have gathered outside one of the homes here, to pay homage to 50-year-old Sukhwinder Kaur, who died on May 13. Days earlier, she had sustained severe burn injuries from a strike by Pakistan, when she was serving her family dinner. Her husband, Lakhwinder Singh, 57; and son Jaswant Singh, 25, too suffered serious burns in the incident, and are being treated in hospital.

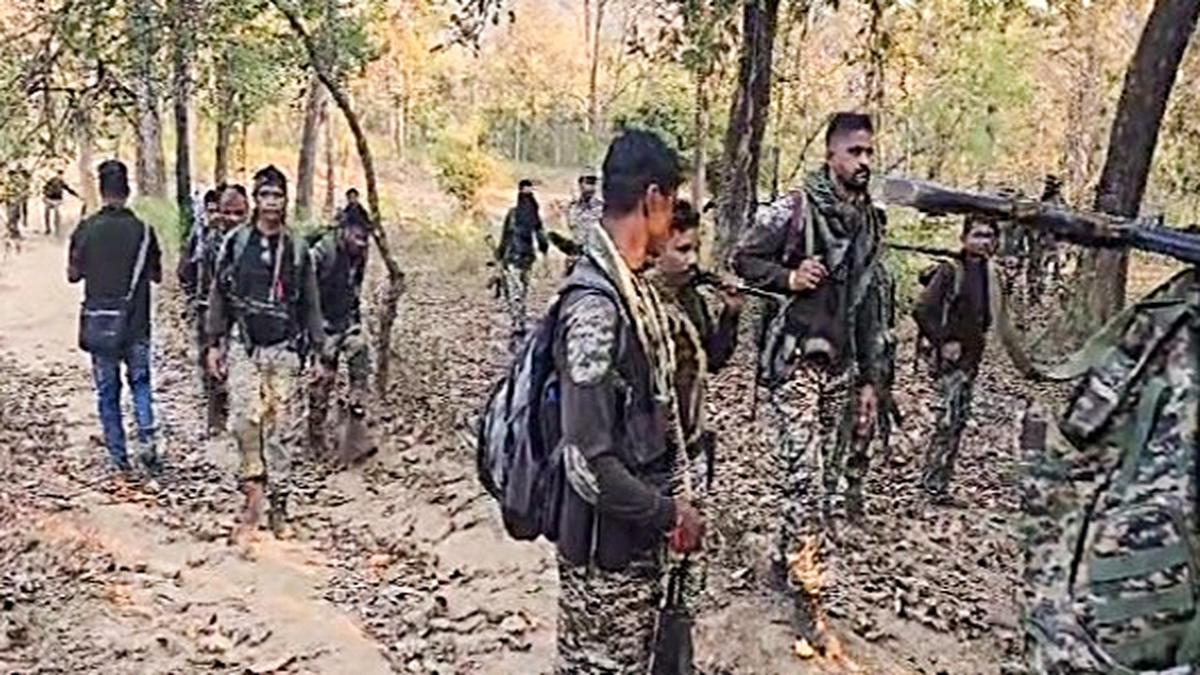

The attack took place during the military confrontation over four days between India and Pakistan, following India’s precision strikes on nine terror targets in Pakistan and Pakistan-occupied Kashmir on the night of May 6-7. Tensions between the two countries escalated after 26 civilians were killed in a terrorist attack in Jammu and Kashmir’s Pahalgam on April 22.

The Resistance Front, an offshoot of the Lashkar-e-Taiba, a terror group with its headquarters in Muridke in Pakistan, initially claimed responsibility for the attack. As a response to India’s initial strikes, Pakistan targeted civilian areas and military installations in India’s border regions of Jammu and Kashmir, Punjab, Rajasthan, and Gujarat.

Sukhwinder’s death has opened the wounds of the people who live in villages which share a border with Pakistan, where life becomes unpredictable every time there is tension between the two countries.

In Pojoke Uttar village, approximately 3 km from the border, when tensions escalated, people began sleeping in fields. With blackouts, and drones hovering in the skies, family members took turns to guard their homes and villages. They switched off the lights before darkness descended fully, understanding what could happen if they did not.

In Habibwala village, barely 2 km from the border, younger men dug bunkers, and women sent children to the homes of their maternal grandparents if they lived away from the border. Malla Singh, a village panchayat member, says about 30 big and small bunkers were made in 10 days.

Scars and strains

A buffalo that got burns during a drone attack by Pakistan at Khai Pheme Ki village in Ferozepur District, Punjab on May 13, 2025.

| Photo Credit:

Shashi Shekhar Kashyap

The authorities took away the remains of the object that fell inside Sukhwinder’s compound, but her car whose bonnet was blown up in the fire is still parked here, charred from the impact on May 9 night. Just a few metres away from the car are three cattle inside a shed. Two have suffered burns and their skins are peeling off. The electric wires passing through the roof of the house are hanging low, half melted; there are blood stains in both rooms and on the veranda.

Neighbours rushed the family of three to the hospital. Sukhwinder was shifted to a bigger facility in Ludhiana, and died four days later. When her body was brought home, the neighbours put together money for tents to be set up on the roadside, so that the villagers could pay their respects without having to stand in the scorching heat.

When Jaswant heard that his mother had died, he insisted on leaving the hospital for a day, despite burns and splinter injuries. “We had just sat down for dinner when something hit our car and there was a blast. Everything went up in flames. Before we could gather our senses, our bodies were burnt,” he says, with a deep sense of loss.

His older brother had died in an accident a few years ago. As he waits for his mother’s body, he turns to his relatives and friends, asking every few minutes when the ambulance will arrive from Ludhiana. Then he asks about his father, who too sustained 70% burns. When Sukhwinder’s body is brought home, Jaswant, who is unable to walk because of the injuries, drags himself from the cot with the help of four people and places his hands on his mother’s forehead.

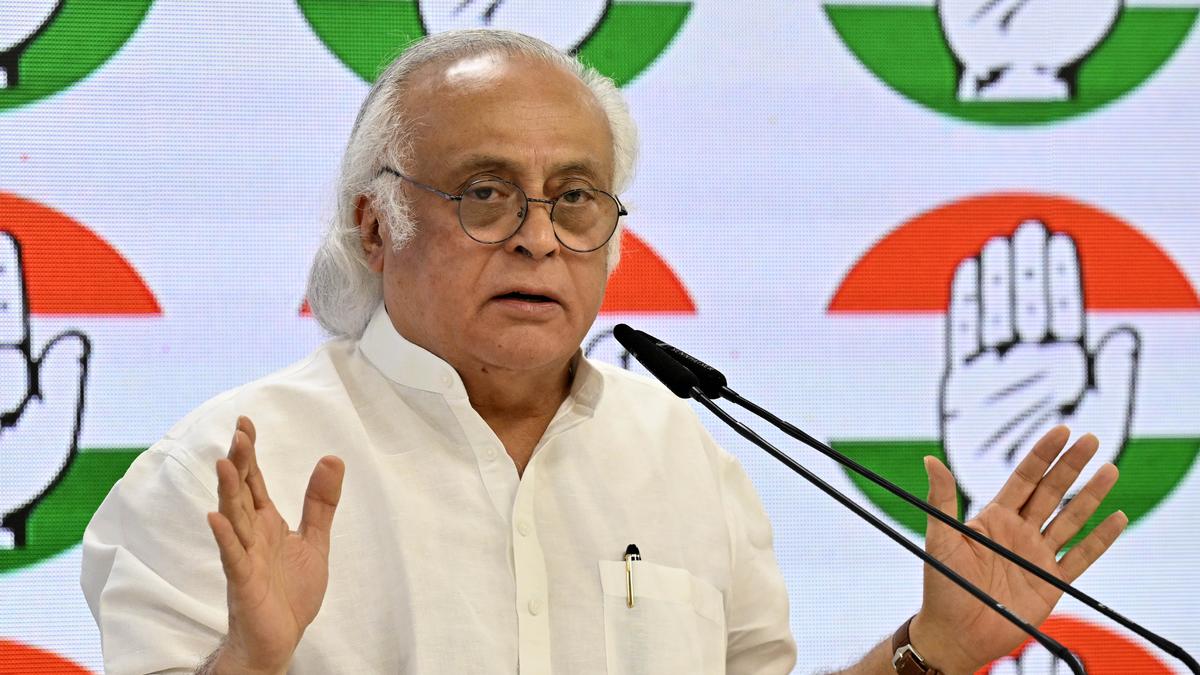

The calm of the village is broken with the wails of the women. The men decide something must be done before the body is cremated. Those who are in mourning start raising slogans demanding ₹1 crore compensation, a government job for one member of the family, and the status of ‘martyr’ for Sukhwinder. Hours after negotiating with government officials and the police, the family cremates the body. Later, the Punjab government offers a ₹10 lakh compensation.

Relatives and people of the village outside the house of Sukhwinder Kaur, who died in the attack in Khai Pheme Ki village in Ferozepur District, Punjab on May 13, 2025.

| Photo Credit:

Shashi Shekhar Kashyap

The bridge to history

In Hussainiwala, a little over 10 km from Ferozepur city, a cluster of villages border Pakistan. Here, many have vacated their homes and gone to live with relatives in places less dangerous. The National Martyrs Memorial, built in memory of freedom fighters Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev Thapar, and Shivaram Rajguru, is in Hussainiwala. Before the tensions, a daily changing of the guard took place, where both sides ceremonially lowered the flags in the evening.

“It was important for us to leave, not because we are afraid of drones or shelling, but because if we hadn’t left, we might have ended up stuck had matters escalated,” says Gomma Singh, a member of the farmers’ union in Gatti Rajjo Ki village in the area. He remembers stories of the 1971 war between the two countries, when Hussainiwala had become a location of conflict between Indian and Pakistani troops. The bridge to Hussainiwala, which was destroyed in that conflict and rebuilt later, is now heavily guarded by Indian troops, and only locals are allowed to pass through. It is covered with a shed.

Gomma says some people have started returning home after the understanding to “stop all firing and military action on land, in the air, and sea” came into effect on May 10, but many are still waiting. He demands that the government “give all of us homes in cities” as living on the border “keeps us in uncertainty”.

Life disrupted

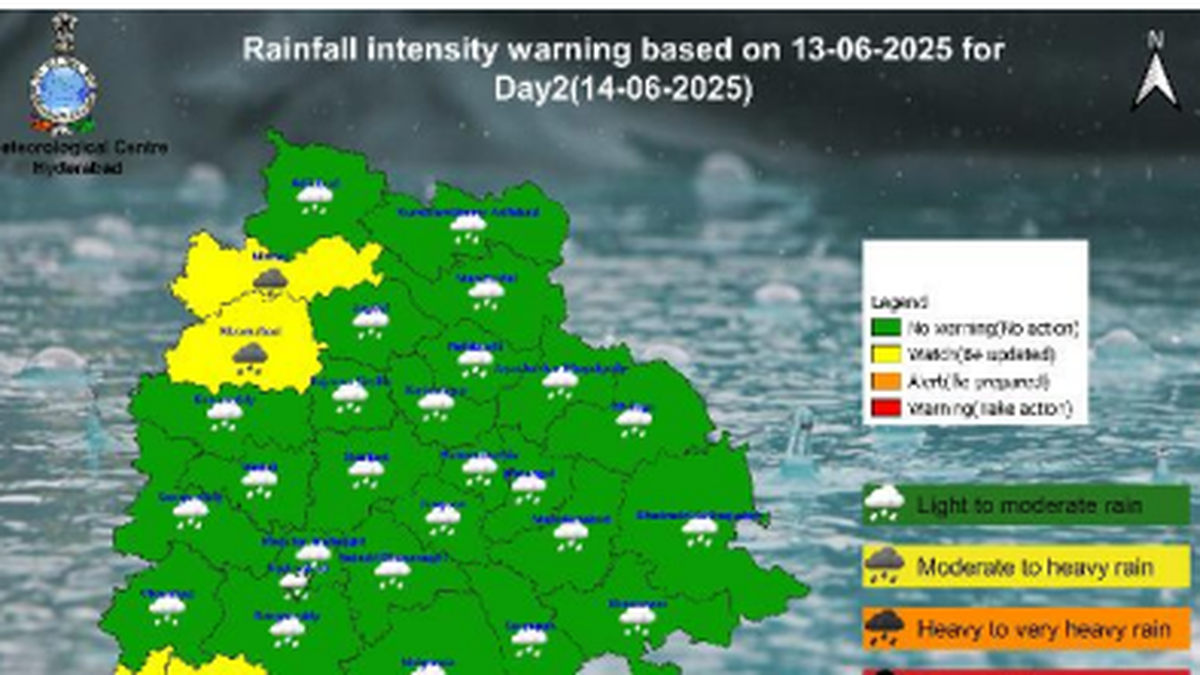

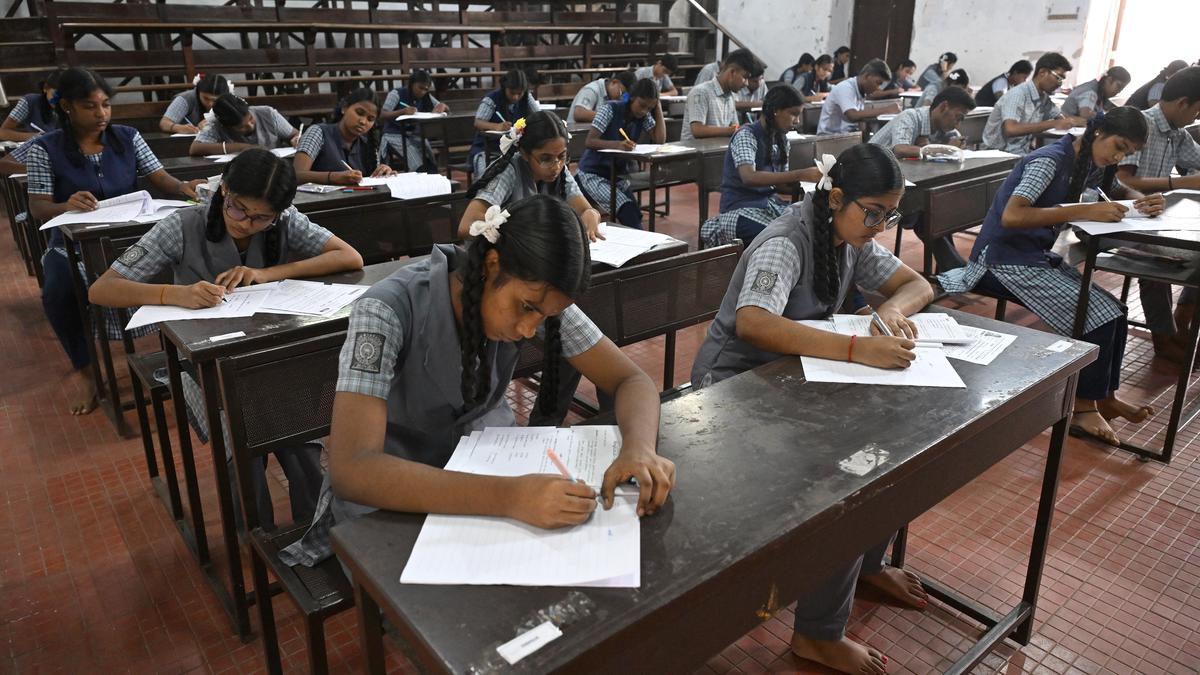

Life in towns and cities in Punjab has also been affected, though cities such as Chandigarh are over 200 km from the border with Pakistan. With extra precautions ordered by the district administration, the people in Ferozepur were forced to cut short family functions and shut businesses after dusk. Rajeev Monga, whose niece got engaged on May 10, had to downscale celebrations. Simran Singh, whose son was preparing for the engineering entrance exam, was unable to reach Bengaluru on the day of the test, as the nearest airport in Amritsar was shut. The family could not get a train ticket in time. Travel agencies and hoteliers are seeing cancellations during the usually hectic school summer vacation.

“War is not good for anyone. Look at the Russia-Ukraine war. Who had thought that it would last for over three years? We shouldn’t pray for war; no one knows whether it will end in five days or in five years,” says Nishant Singh, who runs a hotel and restaurant near Bhagat Singh colony in Ferozepur city.

In Punjab’s Bhatinda, a Haryana labourer was killed and nine others sustained injuries after an unidentified aircraft crashed and went up in flames during the wee hours of May 7.

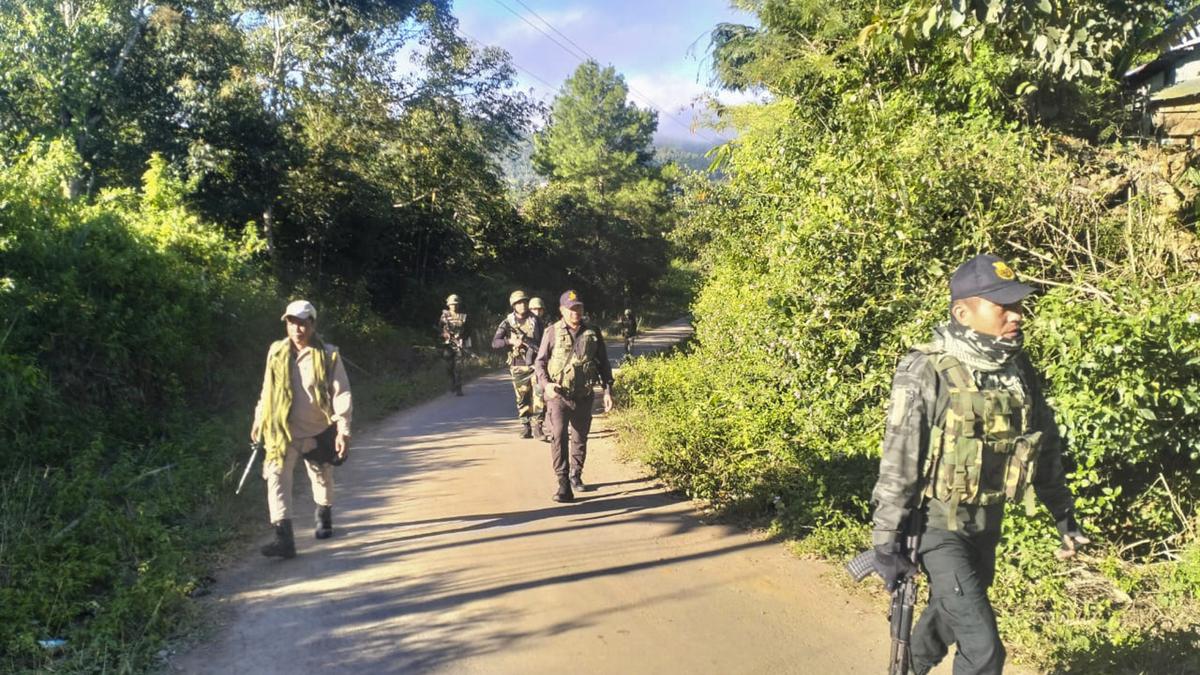

Children and seniors affected

The India-Pakistan border is marked with a barbed wire and on normal days, the Zero Line is guarded by the Border Security Force (BSF). The Army takes over the guard in war-like situations. While guarding the Zero Line, a BSF troop had shot dead a Pakistani intruder close to the Lakha Singh Wala BSF post in Mamdot block of Ferozepur on May 8. It is also from Ferozepur that a BSF constable, Purnam Kumar Shaw, had inadvertently crossed into Pakistani territory on April 23. He was repatriated on May 15.

“My grandchild panicked when a blackout was announced on day one and the intruder was shot at,” says Bariam Singh, 65, from Basti Ram Lal village, smiling at his 16-year-old grandchild. He feels that earlier, wars were fought between men in uniforms; now, they are between machines, drones, and missiles.

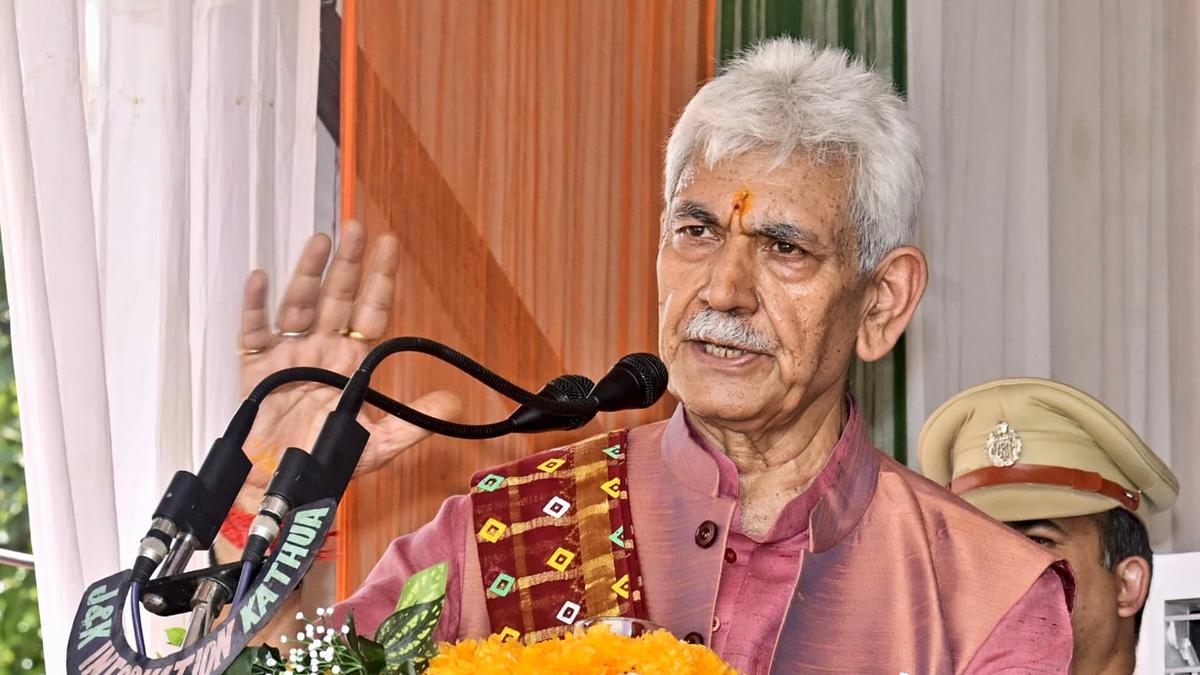

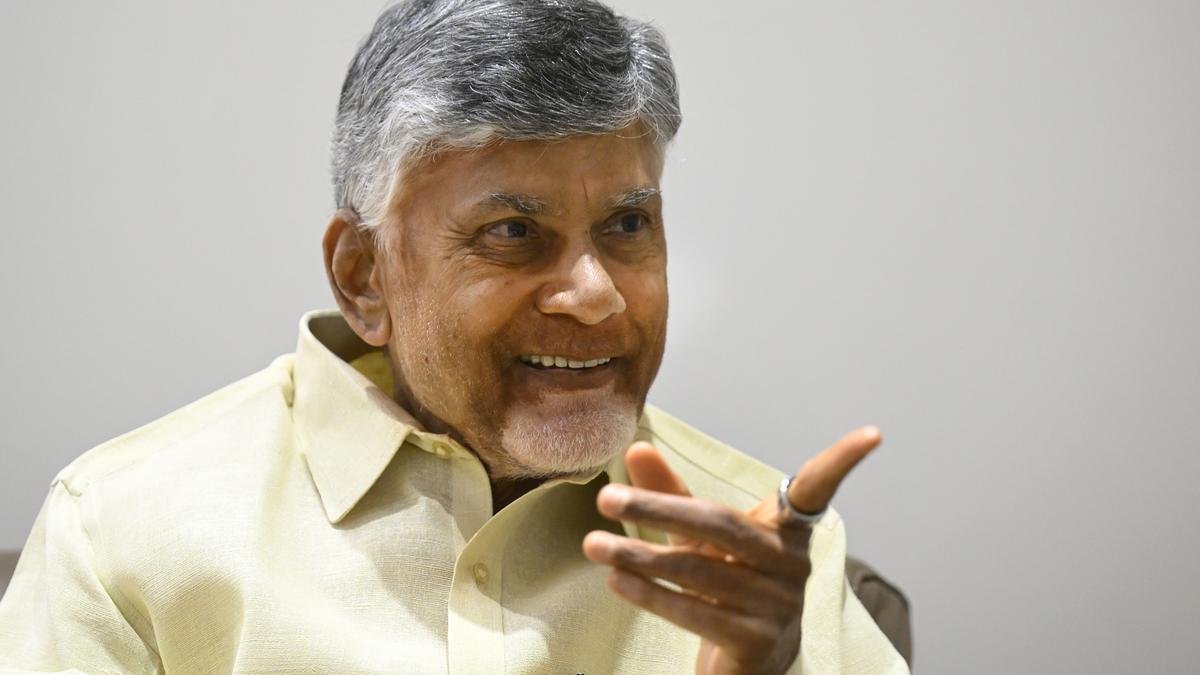

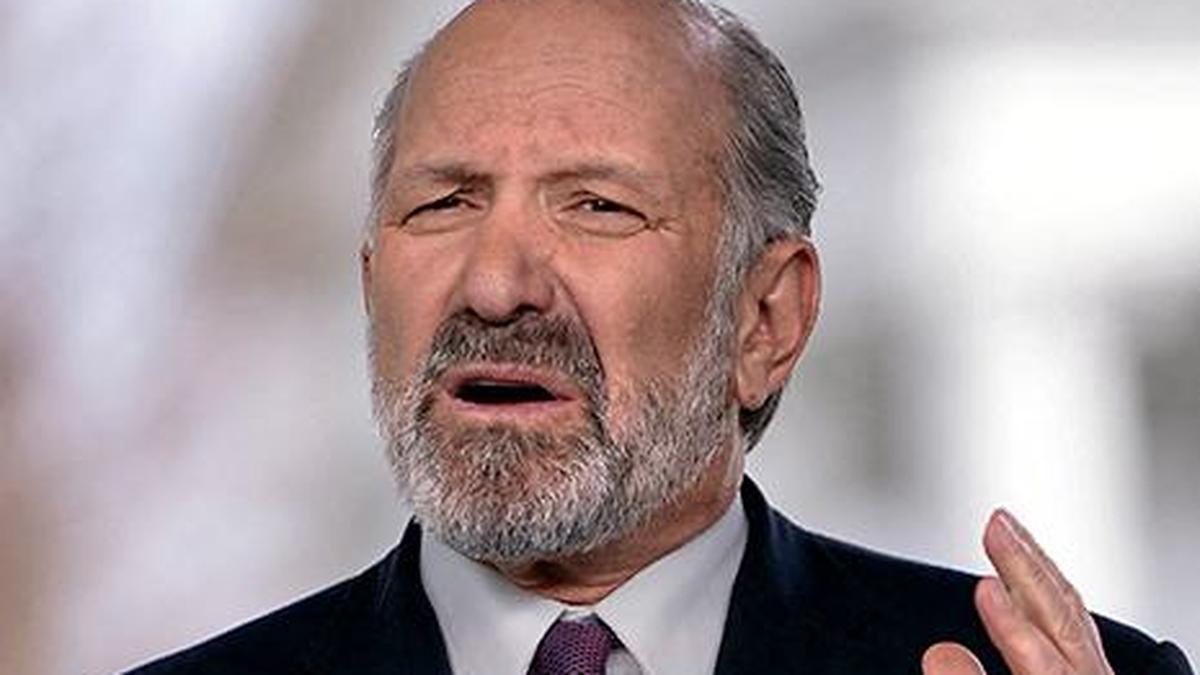

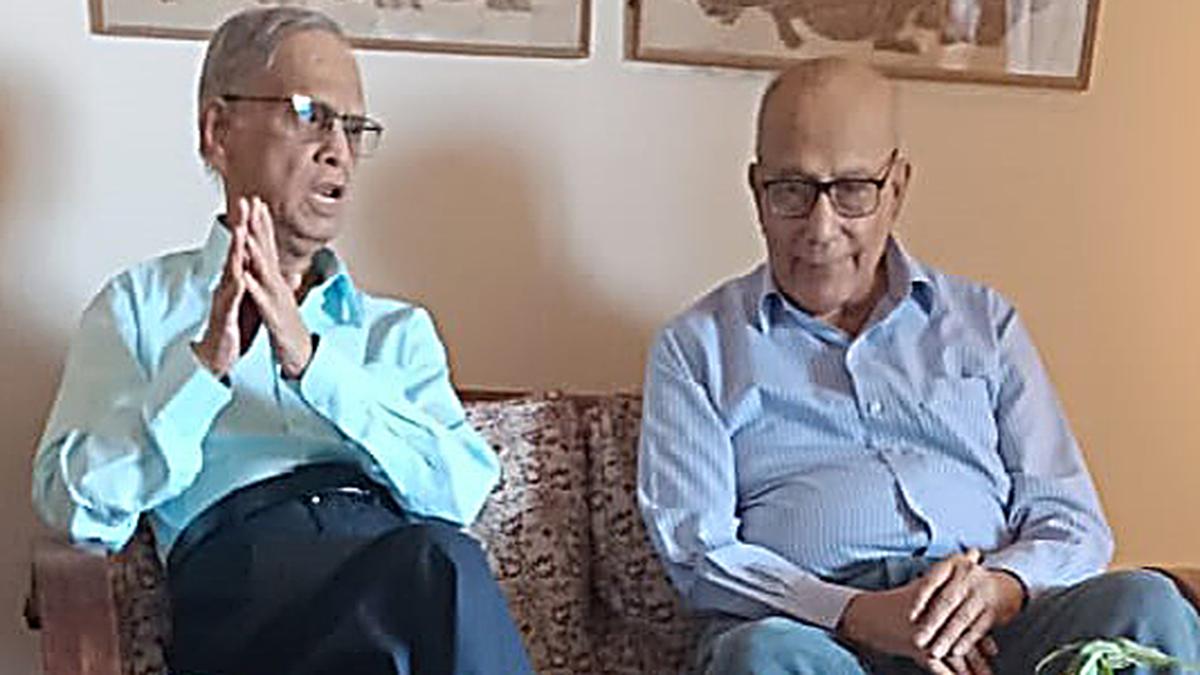

Lt. Gen. Deepender Singh Hooda, who retired as the Northern Army Commander, agrees with Bariam on the way warfare has changed. He says, “Punjab is a key strategic location for both India and Pakistan. After Jammu, this State has a lot of civilians living in border villages. Our neighbouring country has a tendency of attacking civilians to put pressure on the government. This is why Punjab remains one of the worst-affected areas on the border, during wars.”

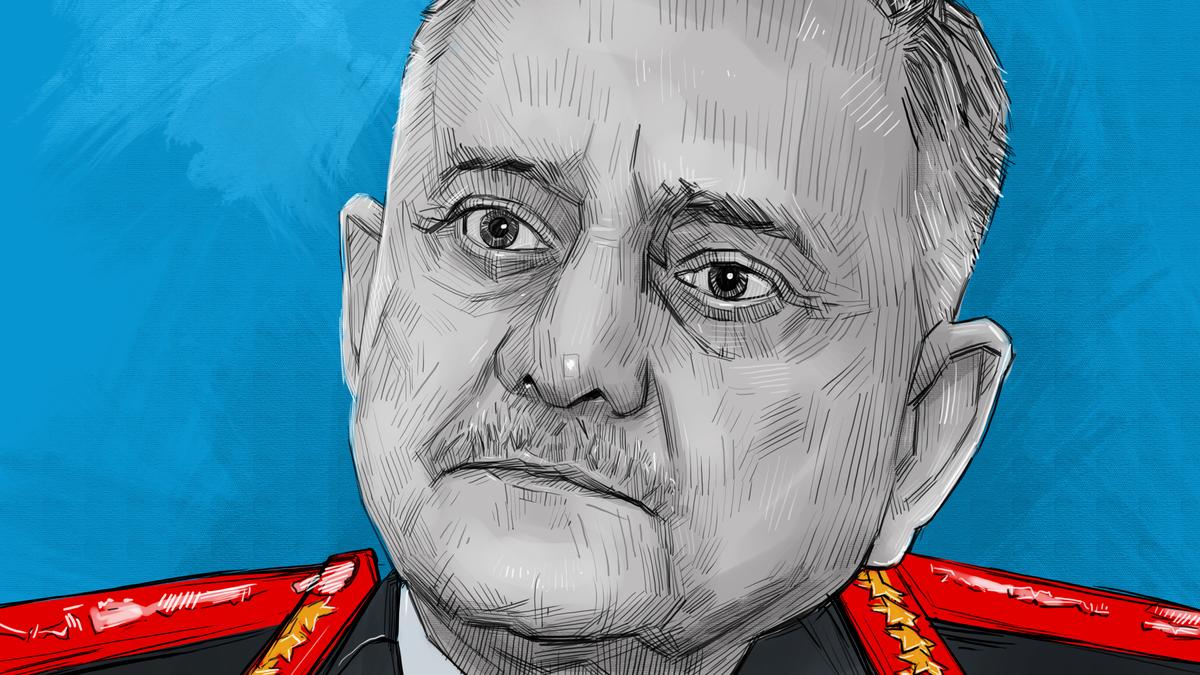

In Kashmir, 18 people died in the targeting of civilians by Pakistan, following Operation Sindoor. Fourteen of them were from Poonch and two were children. Officials say four districts in Jammu and Kashmir — Poonch, Kupwara, Rajouri, and Baramulla — witnessed heavy losses. Lieutenant General Rajiv Ghai, the Director General of Military Operations, has confirmed that the armed forces lost five personnel.

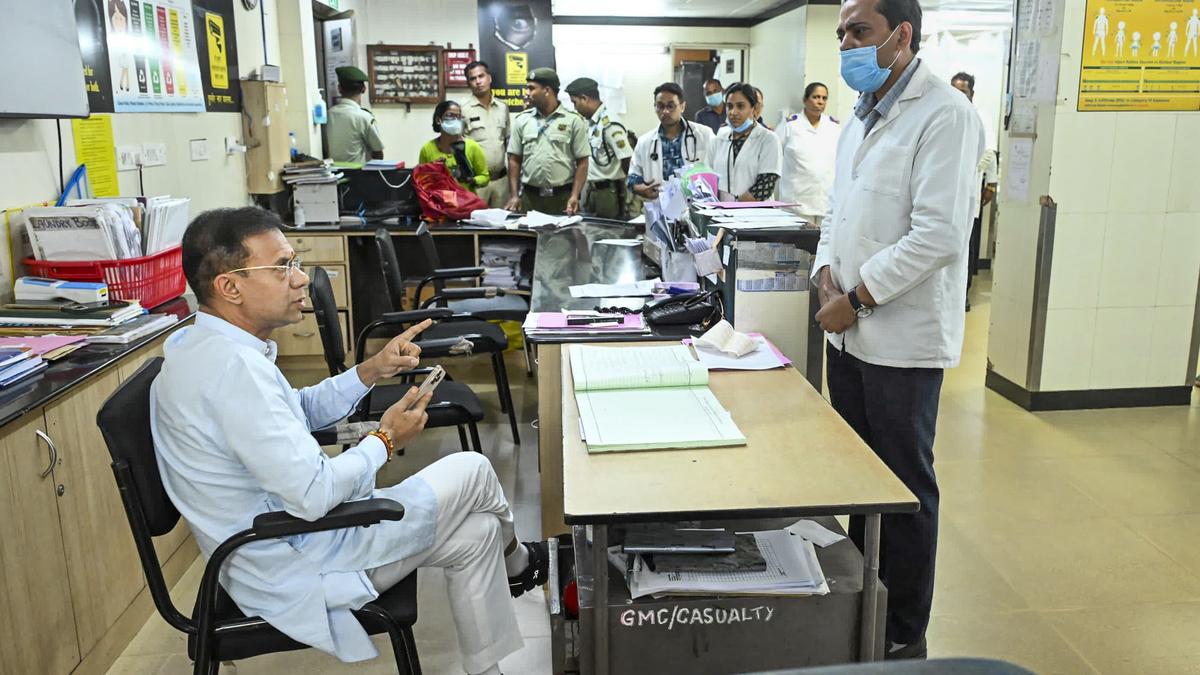

At the Zero Line, retired Army Hawaldar Surjeet Singh has agricultural land that he rushed to harvest when he sensed trouble. Surjeet says people living in border villages get the least facilities, but live under the highest threat. “With the border so close, we always face the threat of firing. But there is no hospital nearby that is capable of treating grievous wounds. We have to go to cities, 40-50 km away,” he says.

Darbara Singh from Basti Ram Lal has just finished feeding his cattle when his wife hands him the phone. His elder son, who is in the Indian Army and is posted in Jammu and Kashmir, has called after three days. “My son says we can sleep peacefully as the Army is awake, guarding the nation,” Darbara says.

Published – May 17, 2025 01:56 am IST