The story so far: Vice President Jagdeep Dhankar on Monday (May 19, 2025) opined the time has come for revisiting a 1991 judgment delivered by the Supreme Court in K. Veeraswami versus Union of India. Insisting upon registration of a First Information Report (FIR) regarding the Delhi cash on fire incident at the residence of High Court judge Yashwant Varma on March 17, 2025; the Vice President said, the 1991 judgment was the genesis of the problem of corruption in the higher judiciary and it was a “judicial legerdemain.”

Who was K. Veeraswami?

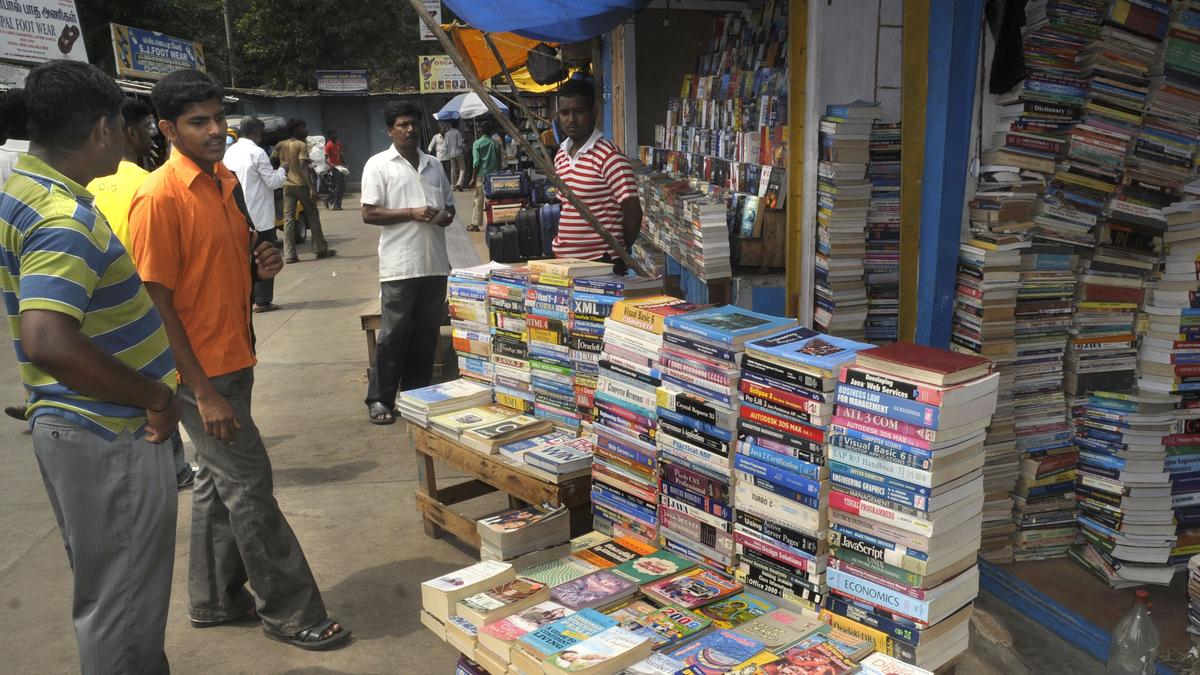

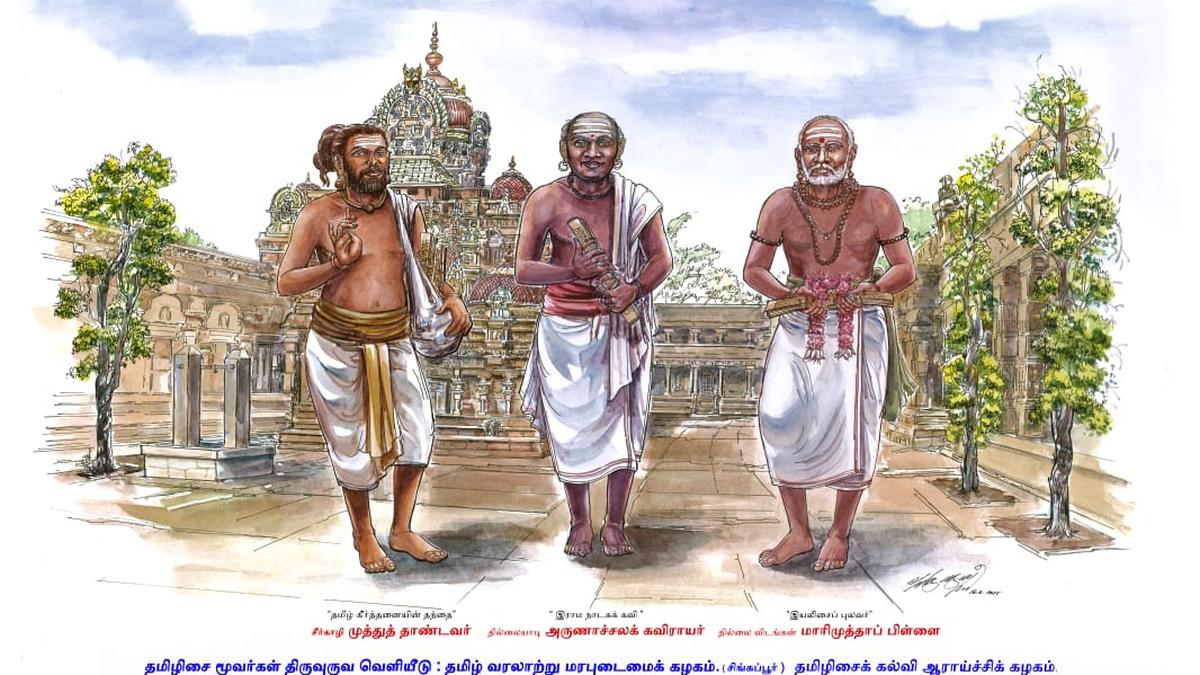

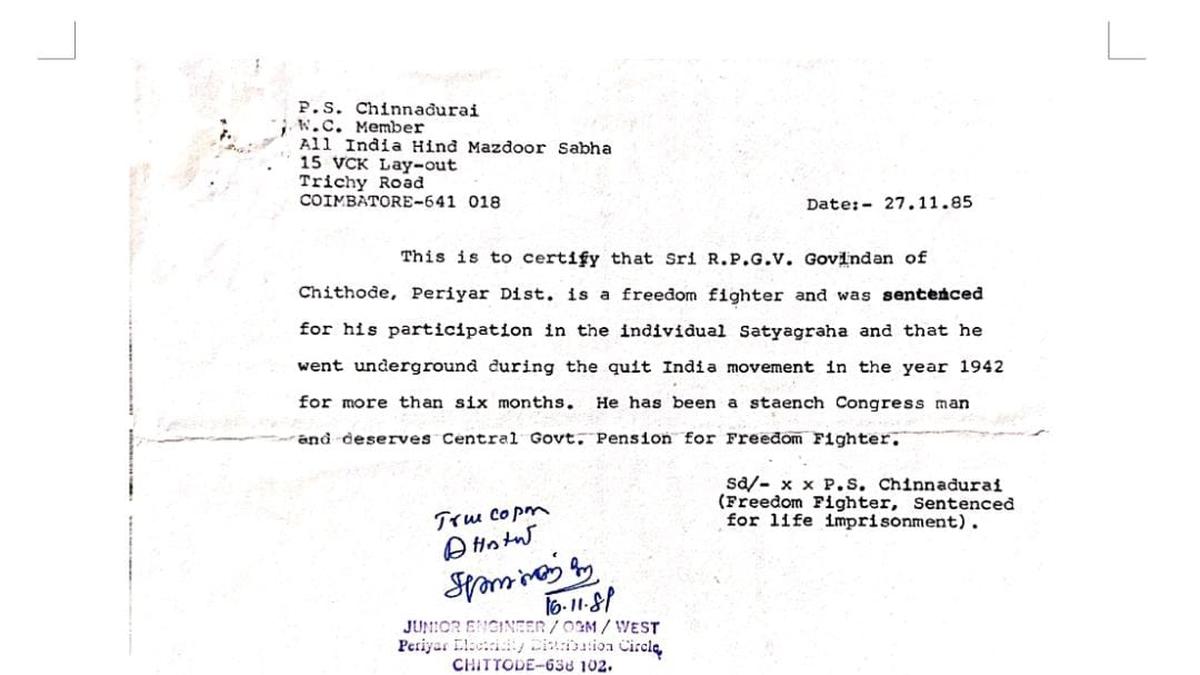

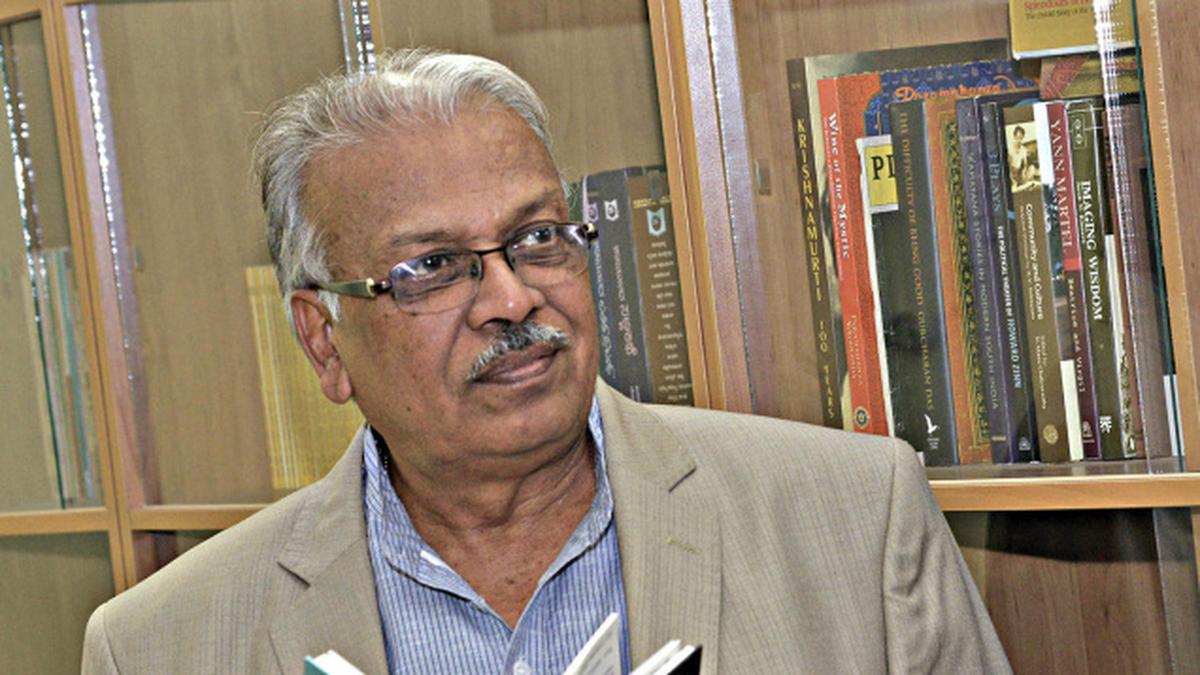

Kuppuswami Naidu Veeraswami had commenced his legal practice by joining the Madras Bar in 1941. He was appointed as Assistant Government Pleader in 1953 and Government Pleader in 1959. He held the post till his elevation as a permanent judge of the Madras High Court in February 1960. On May 1, 1969, he had become the Chief Justice of the High Court and on February 24, 1976, the Central Bureau of Investigation registered a First Information Report (FIR) against him for the offences under the Prevention of Corruption (PC) Act of 1947.

The charge against him was that he had acquired assets worth ₹6.41 lakh disproportionate to his known sources of income not only in his name but also that of his wife Eluthai Ammal and sons V. Suresh and V. Bhaskar between May 1, 1969 and February 24, 1976. A copy of the FIR was filed before a special court for CBI cases in Chennai on February 28, 1976.

On coming to know of these developments, the then Chief Justice proceeded on leave from March 9, 1976 and retired from service on attaining the age of superannuation on April 8, 1976. The CBI, however, proceeded with the investigation into the PC Act case and filed a charge sheet before the special court on December 15, 1977.

How did the case reach the Supreme Court?

After the special court took cognisance of the charge sheet and issued summons, the former Chief Justice filed a petition in the Madras High Court in 1978 to quash the criminal proceedings initiated against him. He contended the prosecution was wholly unconstitutional, without jurisdiction, illegal and void. His plea was heard by a Full Bench (comprising three judges) of the Madras High Court and dismissed by a majority decision of 2:1

On April 27, 1979 Justices S. Natarajan and S. Mohan refused to quash the criminal case. They held there was no necessity for the CBI to obtain sanction for prosecution from a competent authority, as required under Section 6 the PC Act, since Veeraswami had demitted office and was not a Chief Justice on the day when the charge sheet was filed.

However, Justice V. Balasubramaniam, the third judge, took a contrary view and quashed the criminal proceedings on the ground that the CBI had failed to call upon the former Chief Justice to account for the disproportionate assets and then record a finding as to whether his explanation was satisfactory or not and the reasons thereof.

The Full Bench, thereafter, granted a certificate of appeal to the Supreme Court in view of the importance of the constitutional questions involved in the case. The 1979 appeal was heard and dismissed by a five-judge Bench of the top court on July 25, 1991 with a 4:1 majority. While Justices K.J. Shetty, B.C. Ray, L.M. Sharma and M.N. Venkatachaliah held that the PC Act would be applicable to the judges of the higher judiciary too, Justice J.S. Verma alone dissented.

What did the Supreme Court rule?

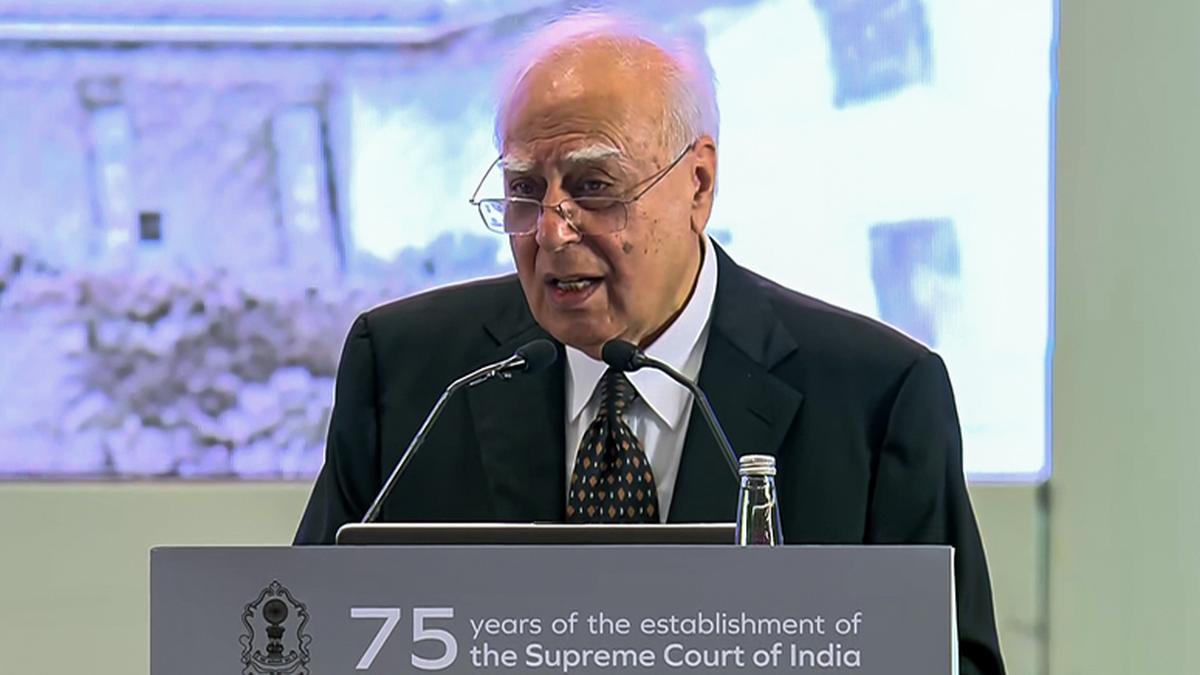

Senior counsel Kapil Sibal had appeared for Veeraswami before the Supreme Court and argued that the PC Act would not be applicable to the judges of the higher judiciary since sanction to prosecute was a mandatory requirement under the Act and there was no single authority who could grant such sanction in the case of High Court or Supreme Court judges. He contended the President could not be regarded as the sanctioning authority since he/she acts upon the aid and advice of the Council of Ministers and therefore, there was every chance of the executive interfering with the independence of the judiciary.

On the other hand, the then Solicitor General A.D. Giri and Additional Solicitor General K.T.S. Tulsi defended the invocation of the PC Act against Mr. Veeraswami and said, the top court could lay down guidelines with respect to issues related to obtaining sanction. After hearing them; Justices Shetty, Ray, Sharma and Venkatachaliah had held that a judge of the Supreme Court as well as the High Courts would squarely fall under the definition of ‘public servant’ under the PC Act and that prosecution could be lodged against them after obtaining sanction.

Justices Shetty, Ray and Venkatachaliah also held that the President would be authority competent to accord sanction for prosecution of a judge but ruled that no criminal case should be registered against a Chief Justice/Judge of a High Court or a judge of the Supreme Court without consulting the Chief Justice of India. If the Chief Justice of India himself was the person against whom allegations of criminal misconduct had been made, then the consultation must be carried out with other judges of the Supreme Court. The three judges, further, ordered that a similar consultation must be held at the stage of examining the question of grant of sanction for prosecution and that the decision on granting sanction should be in accordance with the advice of the Chief Justice of India.

Though Justice Sharma concurred with the other three judges on the issue of applicability of the PC Act to judges of the higher judiciary, he held that the question as to who should be the sanctioning authority need not be answered in Veeraswami’s case since he had retired from service before the filing of the charge sheet and his case did not require any sanction for prosecution.

Justice Verma, in his minority view, disagreed entirely with the other four judges and said the judges of the higher judiciary would fall outside the purview of the PC Act and it would be completely inapplicable to them. Observing that the Parliament may have to enact a new legislation for dealing with corruption among those holding high Constitutional posts, he said: “Any attempt to bring the judges of the High Courts and the Supreme Court within the purview of the Prevention of Corruption Act by a seemingly constructional exercise of the enactment, appears to me, in all humility, an exercise to fit a square peg in a round hole when the two were never intended to match.”

Published – May 20, 2025 05:48 pm IST