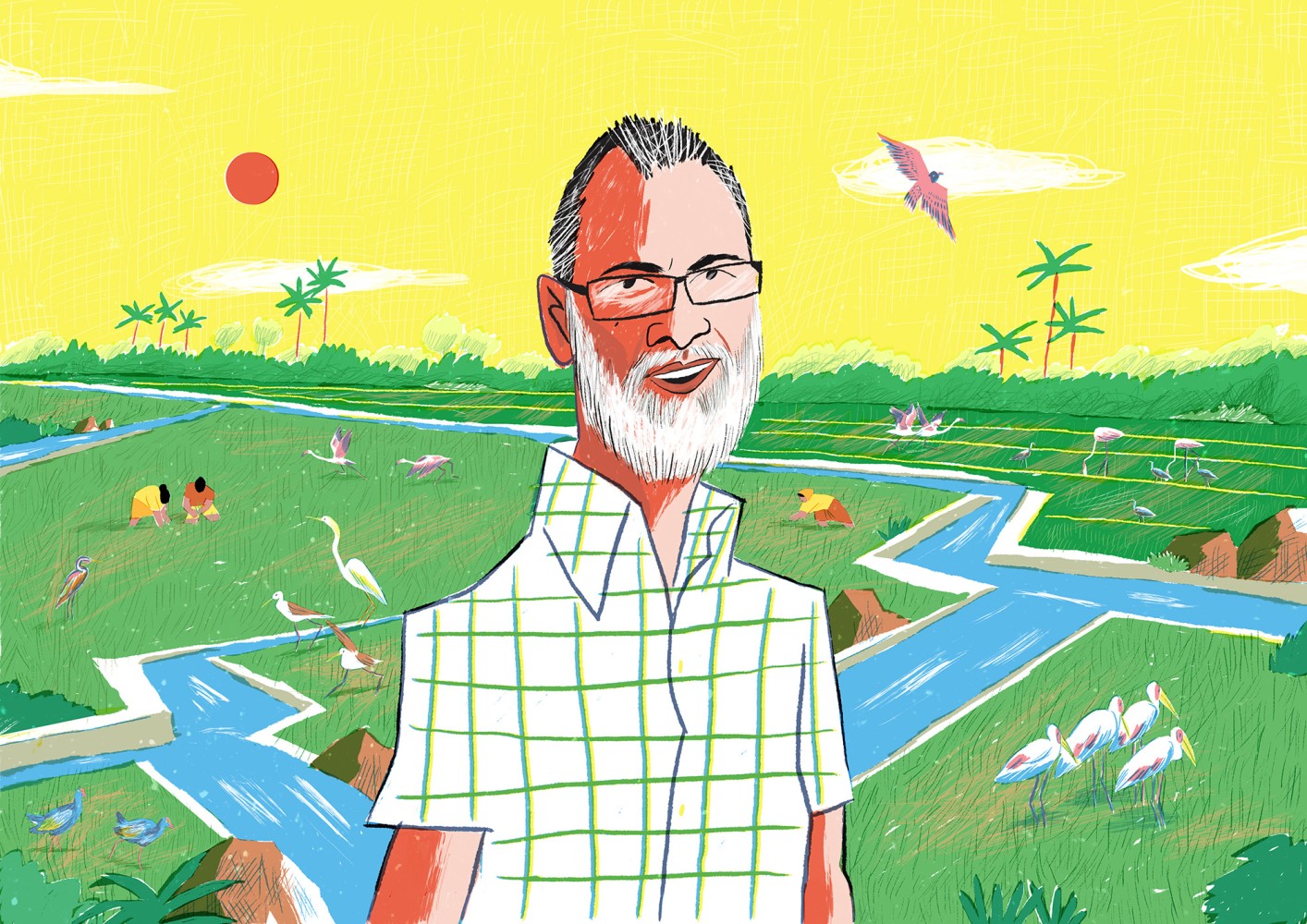

I was researching the 1897 Shillong earthquake, a major seismic event that occurred over a century ago. I started my journey from Thiruvananthapuram in Kerala to Shillong, Meghalaya, to study the field impacts of the great earthquake of 1897, and when I reached Cherrapunji, I had to buy an umbrella. Caught up in that incessant rain in Cherrapunji, I realised I had been chased and overtaken by monsoon clouds. On the southern side of the Shillong Plateau near Cherrapunji, a huge escarpment exists — the massive vertical cliff at Dauki. Standing on a rocky ledge on a foggy morning, I could see the faint outlines of the plains of Bangladesh through wispy clouds. The Shillong Plateau with its elevated position (1.5 to 2 kilometres) acts as a barrier to humid air masses of the Indian Summer Monsoon from the Bay of Bengal forcing the wind to ascend on its southern windward side causing high rain to fall on southern side, with areas like Cherrapunji experiencing record-breaking rainfall. The plateau’s southern flank is one of the wettest places on Earth. The plateau also creates a rain shadow effect on its lee side, reducing rainfall in the Himalayan range downwind. This is why I was intrigued when, in March, the residents said they didn’t get enough usable water despite the rains. This is the type of area from which a new geological time interval was first deciphered, called the ‘Meghalayan Age’ — a global rock boundary signifying a near-global drought about 4,200…This article was originally published on Mongabay