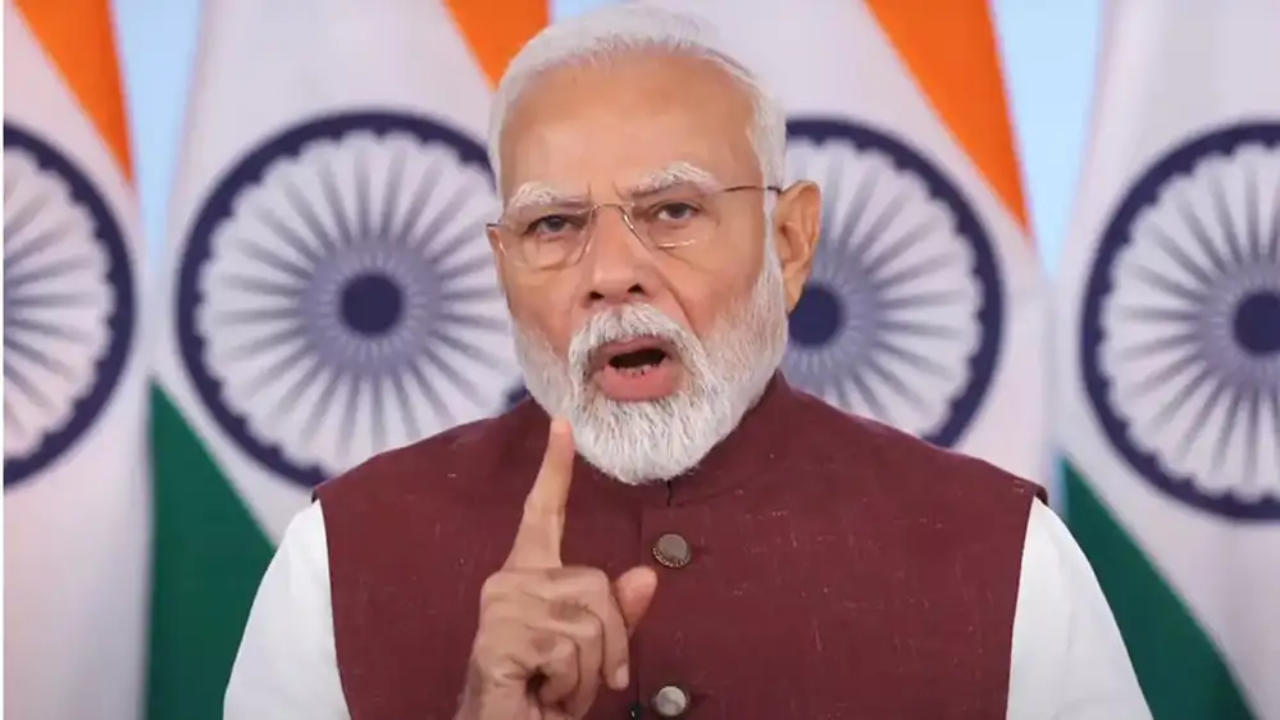

New Delhi: On 1 January 1996, as the world was waking up to a fresh year, the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) received a letter that intended to shake the foundation of the then Narasimha Rao government.

Sent by lawyer-turned-political-activist and Rashtriya Mukti Morcha (RMM) convener Ravindra Kumar, the letter alleged that certain Members of Parliament had given and taken bribes to tilt the scales in favour of the Narasimha Rao government in a no-confidence motion against it. Big names emerged, along with allegations of exchange of crores of rupees.

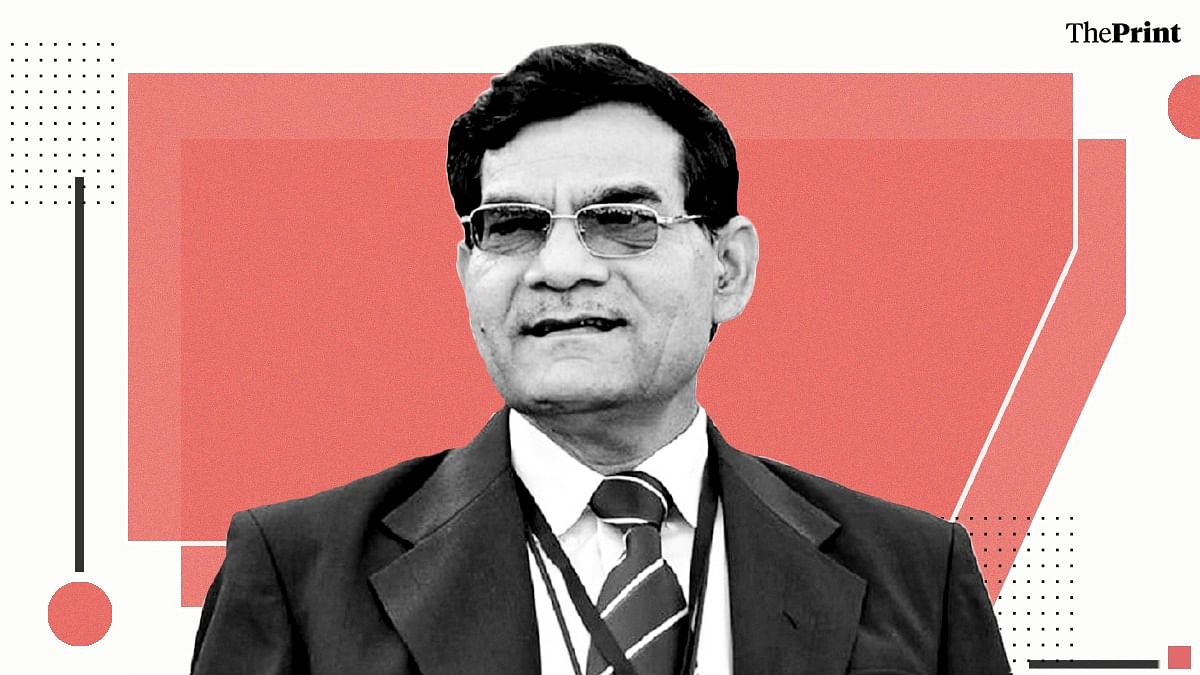

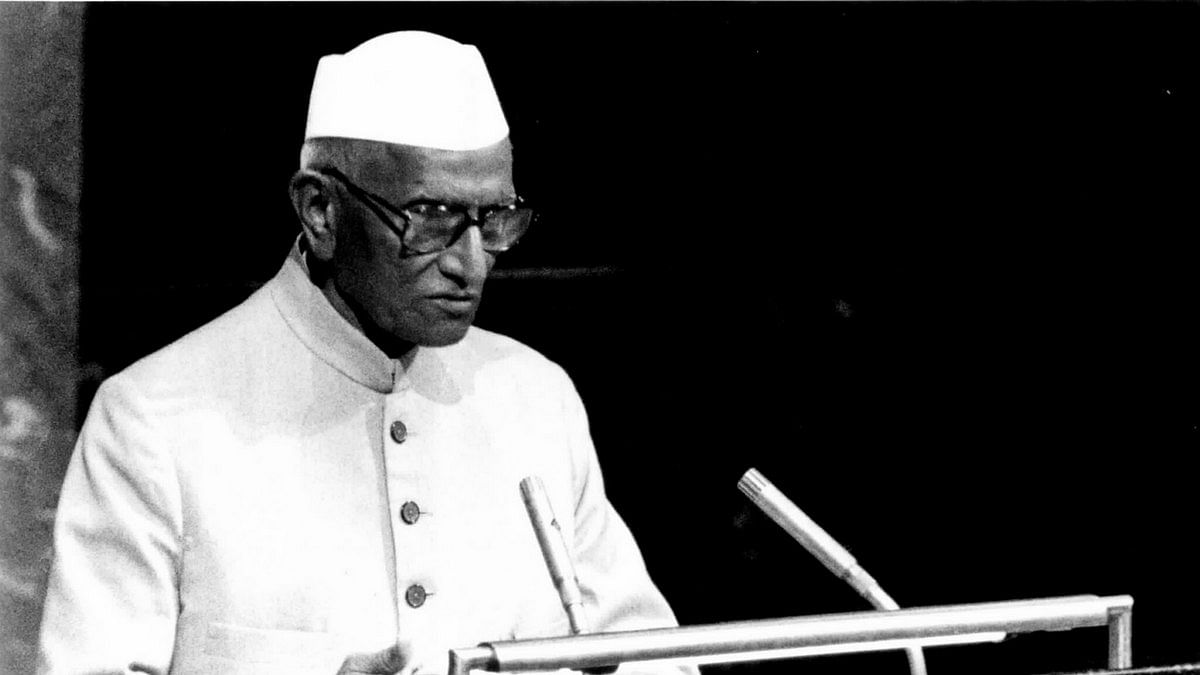

One of the most prominent names in the scandal was veteran tribal leader and then Jharkhand Mukti Morcha (JMM) President Shibu Soren. Born in January 1994, Soren emerged as one of the accused in the case, tying this case and judgement to his legacy.

Soren passed away on Monday at the age of 81, owing to a prolonged illness.

His journey from a social reformer to a prominent politician is often spoken about, but this case, which came to be known as the ‘JMM bribery case’, followed him throughout his life.

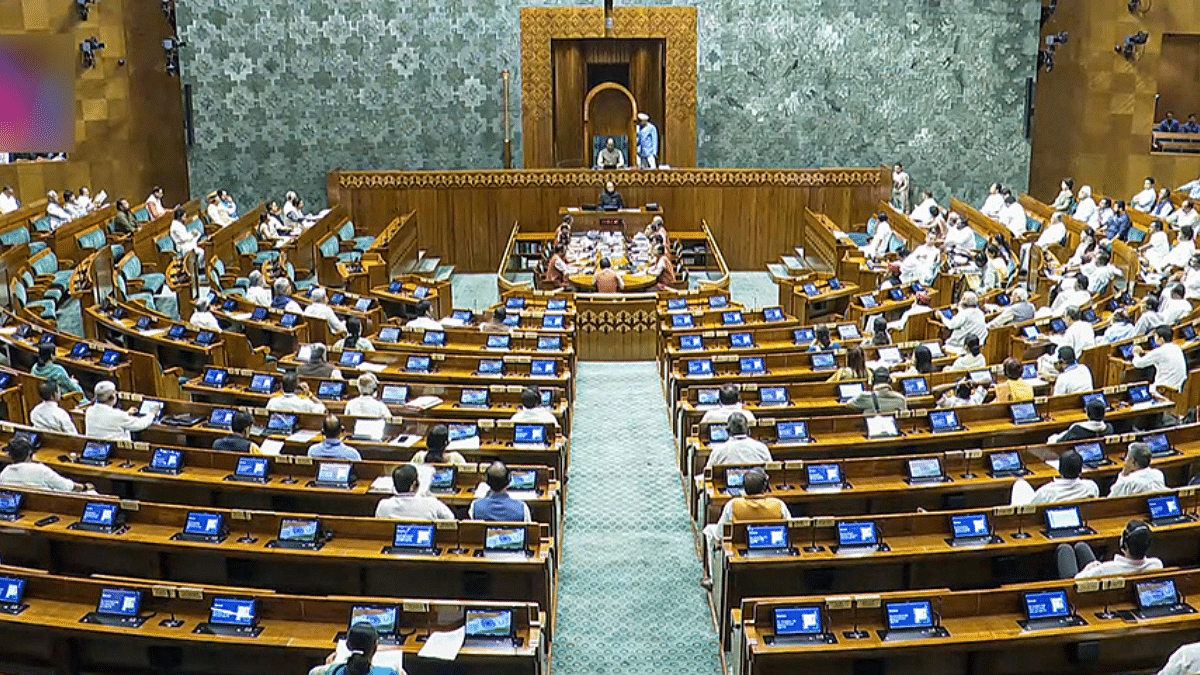

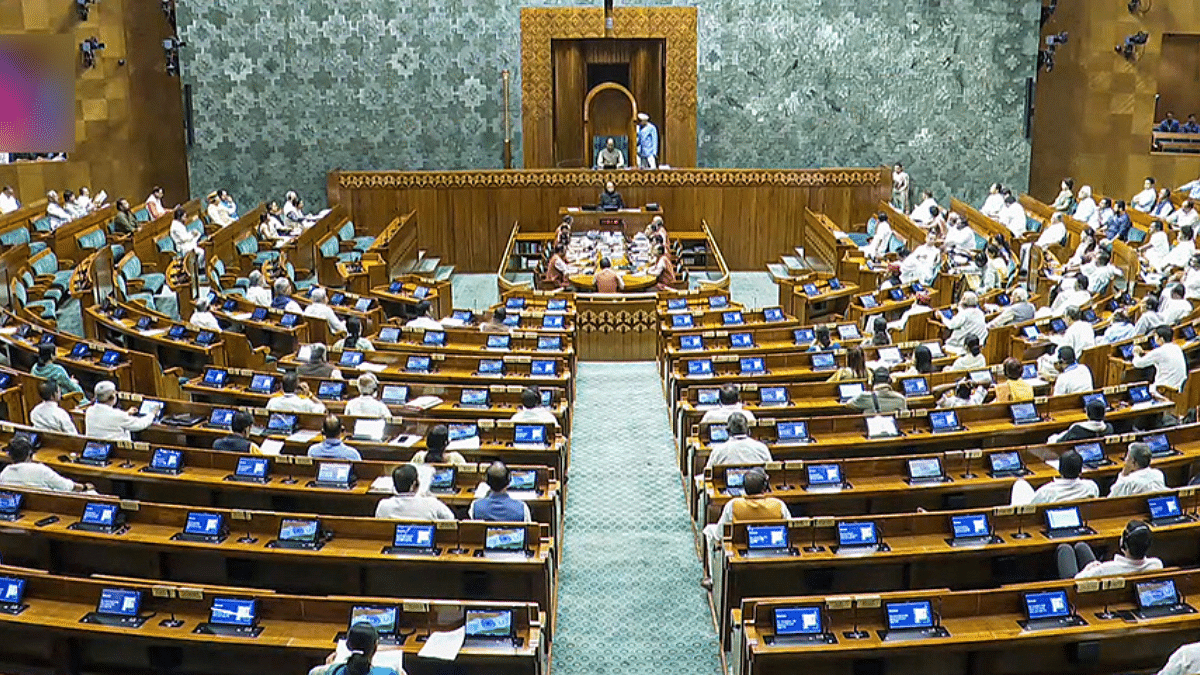

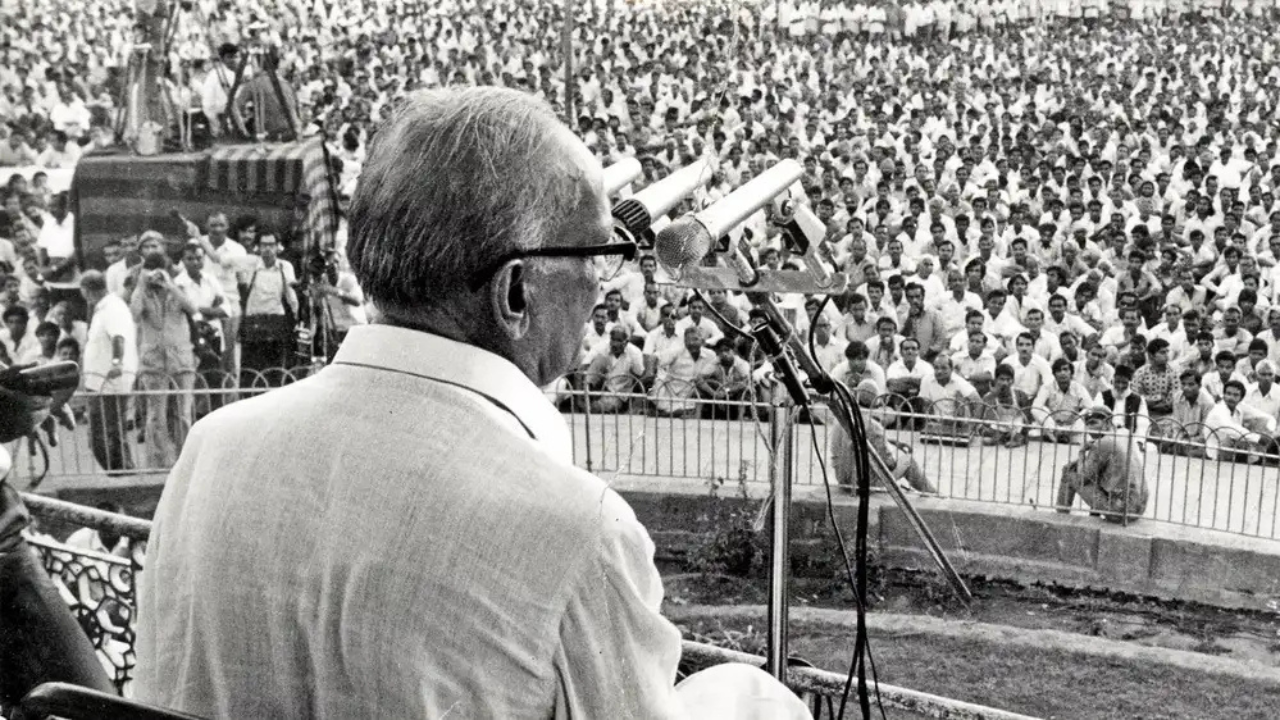

The genesis of this case lies in a no-confidence motion moved against the P.V. Narasimha Rao government in July 1993. Emerging as the single largest party in the 1991 general elections, Congress (I) formed the government with Rao as Prime Minister. The no-confidence motion was moved in the monsoon session of the Lok Sabha two years later by CPI(M) MP Ajay Mukhopadhyaya.

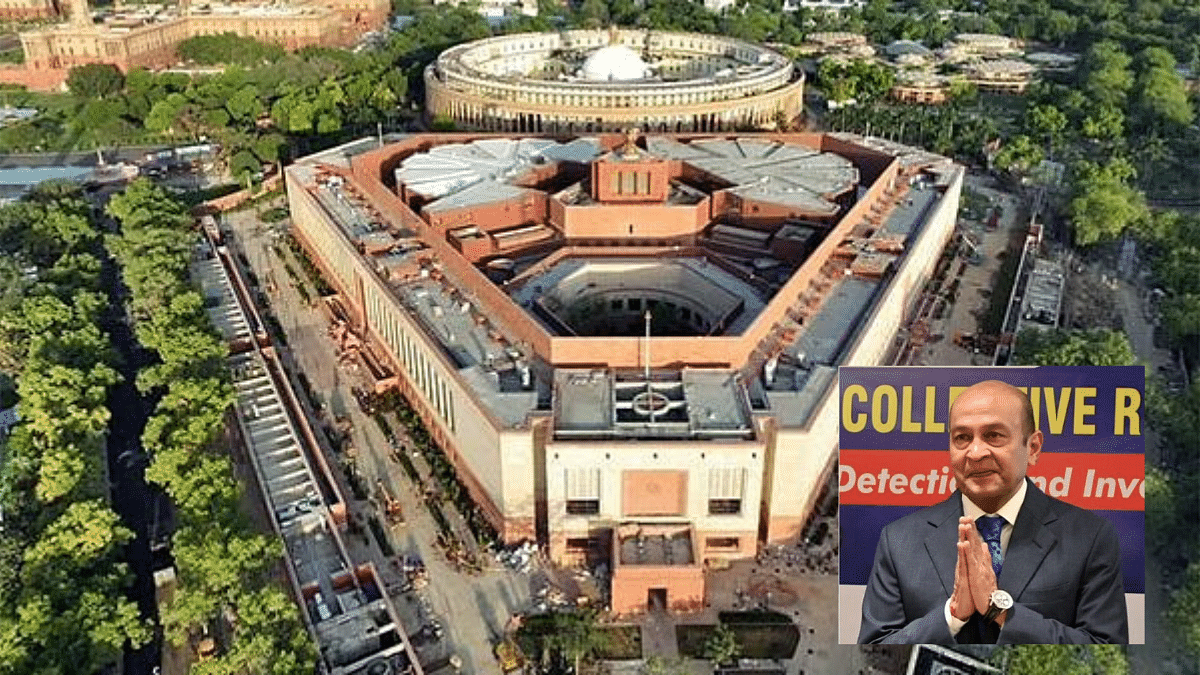

The motion, with 265 votes in favour of the government, was defeated. However, the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) opened an investigation into Kumar’s complaint, which led to a landmark judgment passed by the Supreme Court in 1998. While this 1998 verdict remained the law of the land for 26 years, providing parliamentarians immunity from bribery cases around votes or speeches in Parliament, a case involving Soren’s daughter-in-law led to the overturning of the verdict.

This long journey of the case, as well as the overturning of the judgment, ensured that it remained in public memory for nearly three decades.

Also Read: Soren, the statesman—the man who built Jharkhand, leader of the masses, the ‘irreplaceable’ Guruji

The Supreme Court judgement

Kumar’s complaint opened a Pandora’s box at the time.

It alleged that certain members of Parliament, including JMM’s Soren, Suraj Mandal, Simon Marandi and Shailendra Mahto, and others, owing allegiance to Janta Dal (Ajit Singh Group), received bribes from Rao and others to vote against the no-confidence motion.

What followed was a criminal prosecution against the bribe-giving and bribe-taking Members of Parliament, and a special court in Delhi framed charges against them. However, the MPs demanded immunity, citing Article 105 of the Constitution.

Article 105 provides the Houses of Parliament, their members, and their committees with powers and privileges. Among other things, the provision says that “no member of Parliament shall be liable to any proceedings in any court in respect of anything said or any vote given by him in Parliament or any committee thereof”. Article 194 provides the same immunity to MLAs.

A five-judge bench of the Supreme Court ruled in favour of the bribe-taking MPs in 1998, with a 3:2 majority. The court said that Article 105 “protects a Member of Parliament against proceedings in court that relate to, or concern, or have a connection or nexus with anything said, or a vote given, by him in Parliament”.

The court ruled that the MPs who accepted the bribe and voted on the no-confidence motion would be immune from criminal prosecution for the offences of bribery and criminal conspiracy, as the alleged kickbacks were ‘in respect of’ a parliamentary vote. However, the court ruled that Ajit Singh, a party to the conspiracy but who did not cast a vote, will have no protection from prosecution.

The judgment saved Soren, leading to his discharge by the trial court, but could not save former PM P.V. Narasimha Rao and his cabinet colleague Buta Singh because the court said that the immunity could only apply to the alleged bribe-takers and not bribe-givers. Rao and Singh were both convicted by a trial court in 2000, but in 2002, the Delhi High Court acquitted them.

The undoing

The 1998 judgment of the Supreme Court was, however, overturned by the apex court in March 2024.

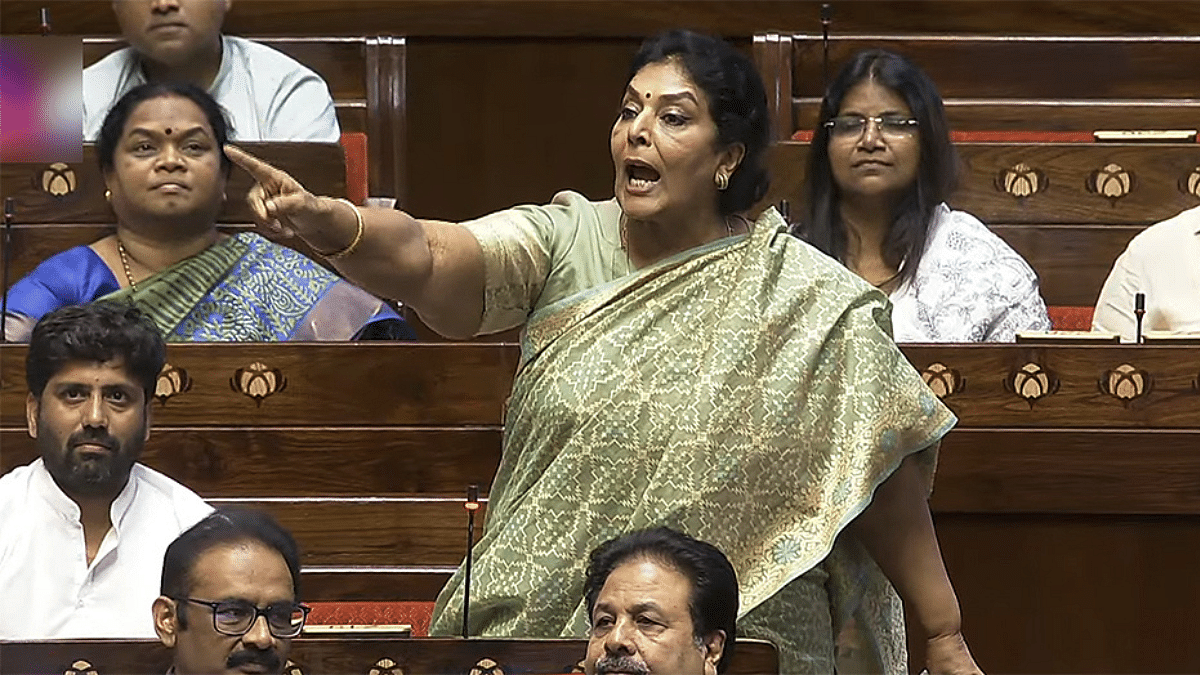

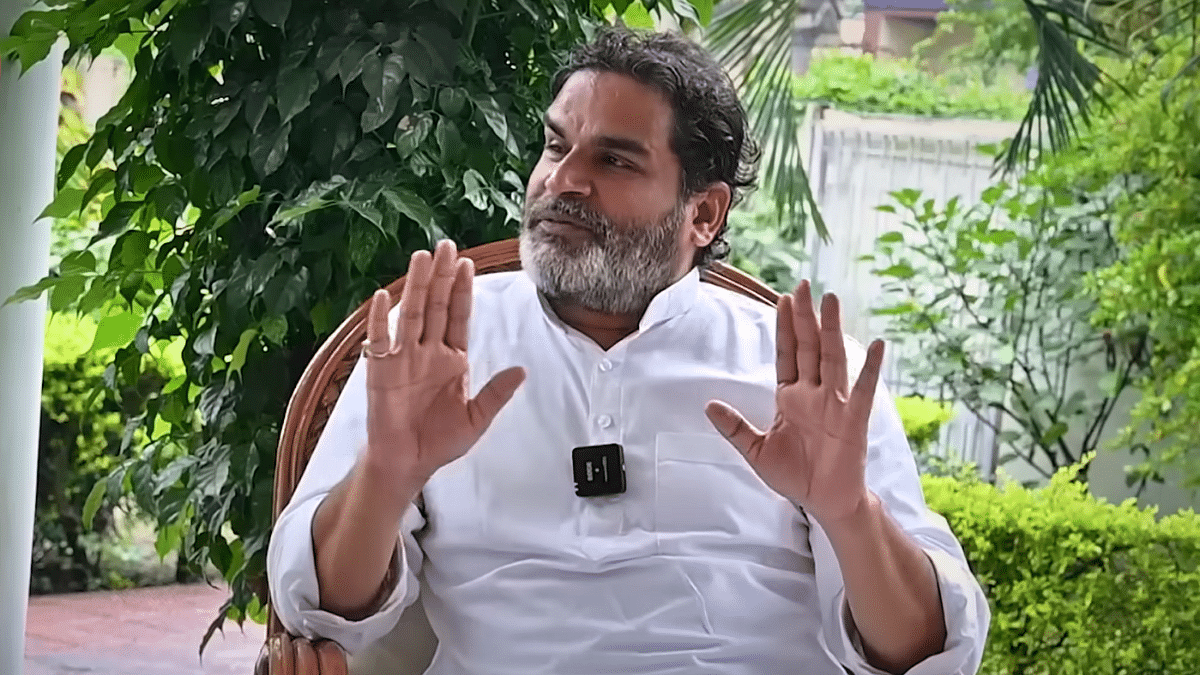

And the undoing was a result of a petition filed by Soren’s MLA daughter-in-law, Sita Soren.

Soren, then a member of JMM, was accused of accepting a bribe to vote for a particular candidate in the Rajya Sabha elections. While she did not finally vote for him, a criminal prosecution was launched against her by the CBI, and the court took cognisance of offences under provisions of the Prevention of Corruption Act, along with Section 120B (criminal conspiracy) of the Indian Penal Code.

While Sita tried to take shelter under the Supreme Court’s 1998 judgment, the Jharkhand High Court ruled in February 2014 that the principle under which the court did not grant Ajit Singh immunity would apply to her as well, since she did not finally vote for the candidate she allegedly took a bribe for.

Sita challenged the high court judgment in the Supreme Court in March 2014.

Last year, a seven-judge bench of the Supreme Court overturned the 1998 judgment, ruling that Parliamentarians do not enjoy immunity under Articles 105 and 194 in cases of bribery allegations.

Days after the judgment, Sita joined the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), months ahead of the assembly elections in Jharkhand, saying she had been “isolated by the party and family members” ever since the death of her husband, Durga Soren.

(Edited by Madhurita Goswami)

Also Read: In Jharkhand, BJP is charging ahead with its campaign, while JMM is left steering ally Congress’s ship