Every day, Jitender Kumar, in his early 30s, travels from Bahadurgarh city to Otha village in Nuh district, Haryana, 131 kilometres away. Kumar is a Hindi teacher at the Senior Secondary School in Otha, and takes a bus and an auto to reach the children he guides.

It’s a hot, humid day in May, just before the school breaks for summer vacation. Kumar rests his head on a plastic chair, under a fan placed inside a 10×12-foot classroom. The electricity may go off any time, and then the class will sometimes move to the shade of a tree.

The walls are blue, chipped; the grey cement floor is cracked, and students sit on a torn, dusty cotton mat, their bags beside them on the ground. The fan doesn’t reach the corners of the room. As the bell rings for lunch, the children squat in rows. Each is given a thali: watery dal and some rice. There is very little space to move around, but the children behave as they would in any other school: playfully collapsing on to each other, some smiling, some bored.

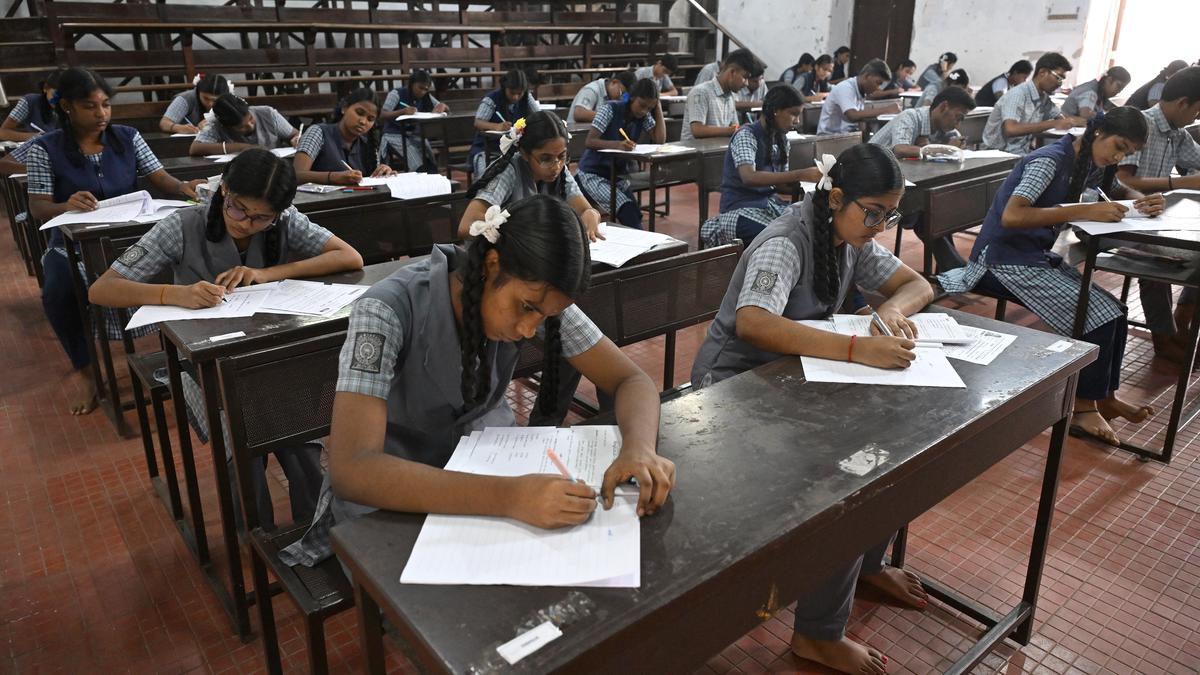

Kumar tries to cool off after having spent a day juggling subjects he barely knows. A postgraduate teacher (PGT), qualified to teach Hindi in the senior school, he also muddles through the English texts with students of Class 12. There has been no English teacher here since December 2022. This year, Kumar taught 13 children; all failed in the Haryana School Education Board (HSEB) examinations.

In 2025, Nuh performed the worst in the results across Haryana districts. Class 10 recorded a pass percentage of 73.90 (up to 13,862 students appeared; 10,244 passed), as per Haryana’s Education Department. Class 12 registered a pass percentage of 45.76 (only 7,588 students appeared; 3,472 students passed). The top results were from Rewari at 96.85% in Class 10, and Jind at 91.05% for Class 12.

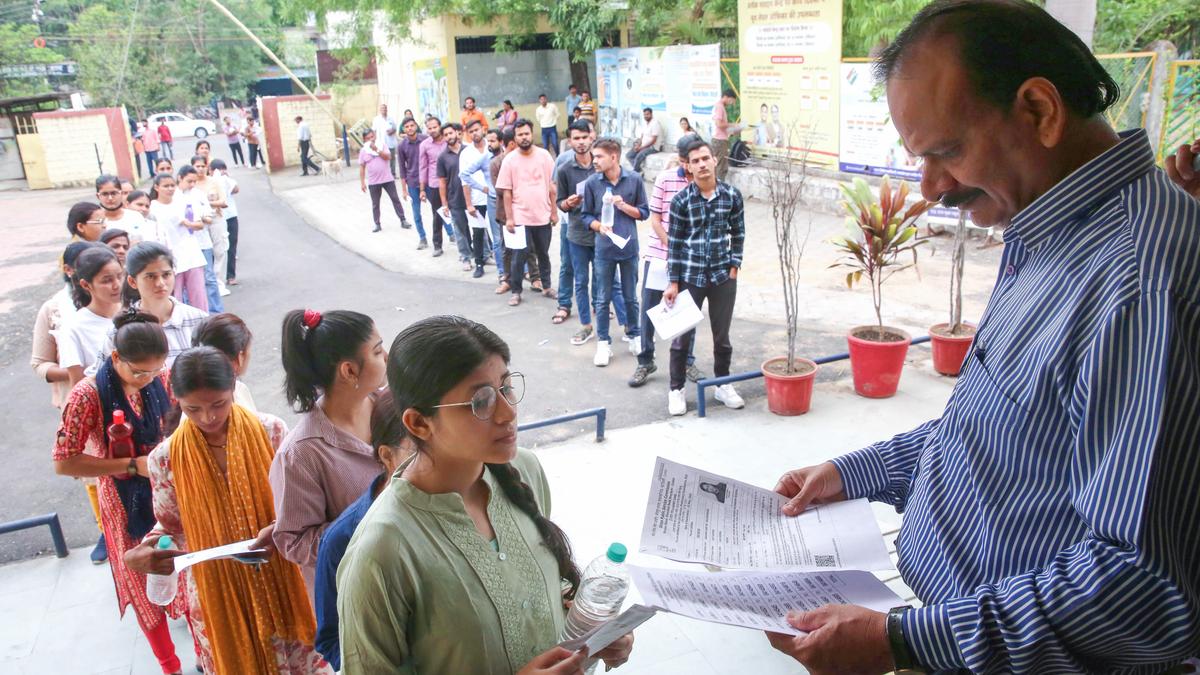

Principals, teachers, and the administration are in agreement that the results were poor this time because the government has begun cracking down on cheating over the past couple of years. In the 2025 board examination, 599 UMCs (unfair means cases) were registered with the administration, compared to 918 in 2024, 1,813 in 2023, and 3,570 in 2022.

“The board displayed unprecedented strictness to curb the menace of cheating during the exams. Disciplinary action was initiated against 135 people, including 109 invigilators and 20 centre superintendents, for dereliction of duty. As many as 16 FIRs (first information reports) were lodged against 74 people across the State,” HSEB Secretary Munish Nagpal says.

As per the district administration, Nuh has 142 senior secondary schools. Only 20 recorded a pass percentage of over 80, while 37 schools registered below 33%. In two schools, no child passed.

Nuh’s under-development

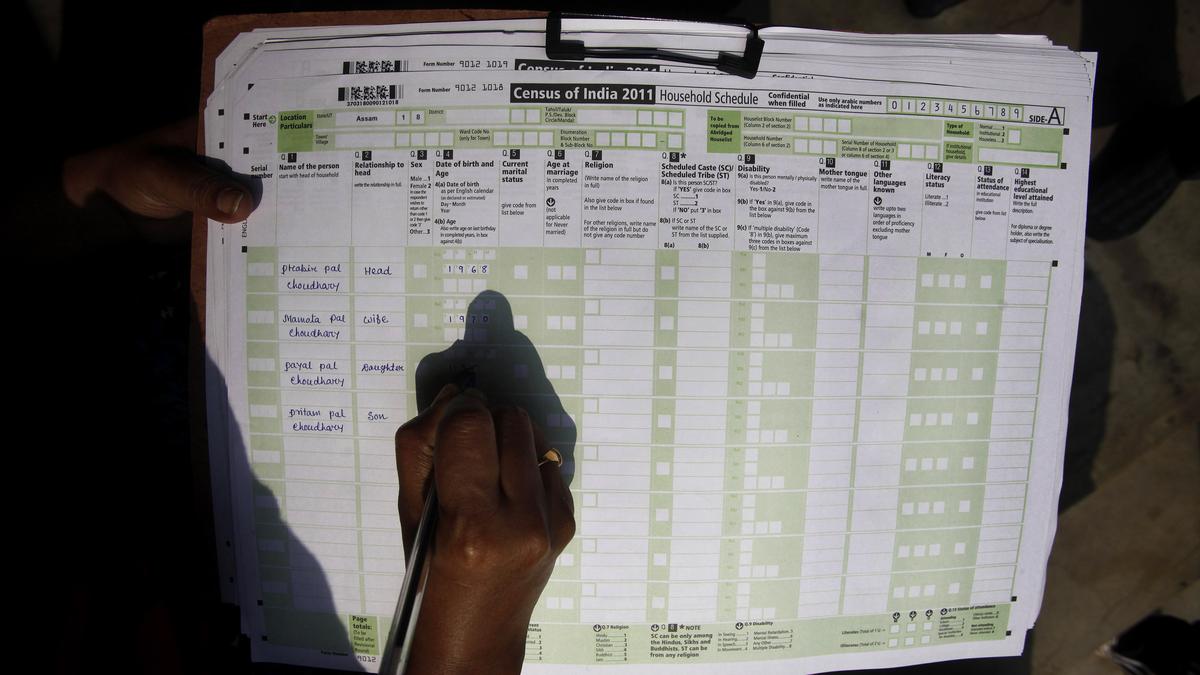

Nuh shares a border with Gurugram, monikered Millennium City, with high-rise corporate offices and condominium complexes that come with swimming pools and lawns. Nuh, with approximately 88% of its population residing in rural areas, is located in the Aravali hills. Roads have not reached here, water is scarce, and there is no university. The literacy rate in Nuh is 56%, out of which 73% are men and only 27% women. According to 2011 Census, the literacy rate in Haryana is 75.55%.

The district was once part of Mewat, but was carved out 20 years ago. Rajasthan, Haryana, and Uttar Pradesh intersect at Mewat, a belt of villages known to be a hotspot for cybercrime. There are over 10.8 lakh people in Nuh, predominantly the Meos, who are Muslim farmers, as per the district administration.

In 2018, the government think tank, NITI Aayog, pegged Nuh as India’s most backward district. That year, Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced the Aspirational Districts Programme that aims to transform 112 of India’s most under-developed districts.

The region’s infrastructure is so poor teachers from other districts don’t want to live and work here. In 2017, a Mewat cadre of teachers was started to tackle this. However, teachers from other parts of Haryana continued to be posted in Nuh. They go to court, citing the creation of the Mewat cadre for the area, to avoid coming here. Nuh’s District Education Officer Ajit Sheoran says that with a new batch of the cadre joining from the next academic year, most Junior Basic Training (primary school) positions will be filled.

No school for daughters

Inside Sonkh Village in Nuh, 60-year-old Jarsheed lies down on his charpoy. His son sits next to him, while his daughters go about their day: one cleans the cows, another cooks. Jarsheed works as a labourer, but is finding it hard to work, given there are many younger men to do the same job. His wife, Hasan Bashri, 60, says the couple has eight daughters and a son. Haryana has a sex ratio of 879, one of the lowest in the country, as per the last 2011 Census.

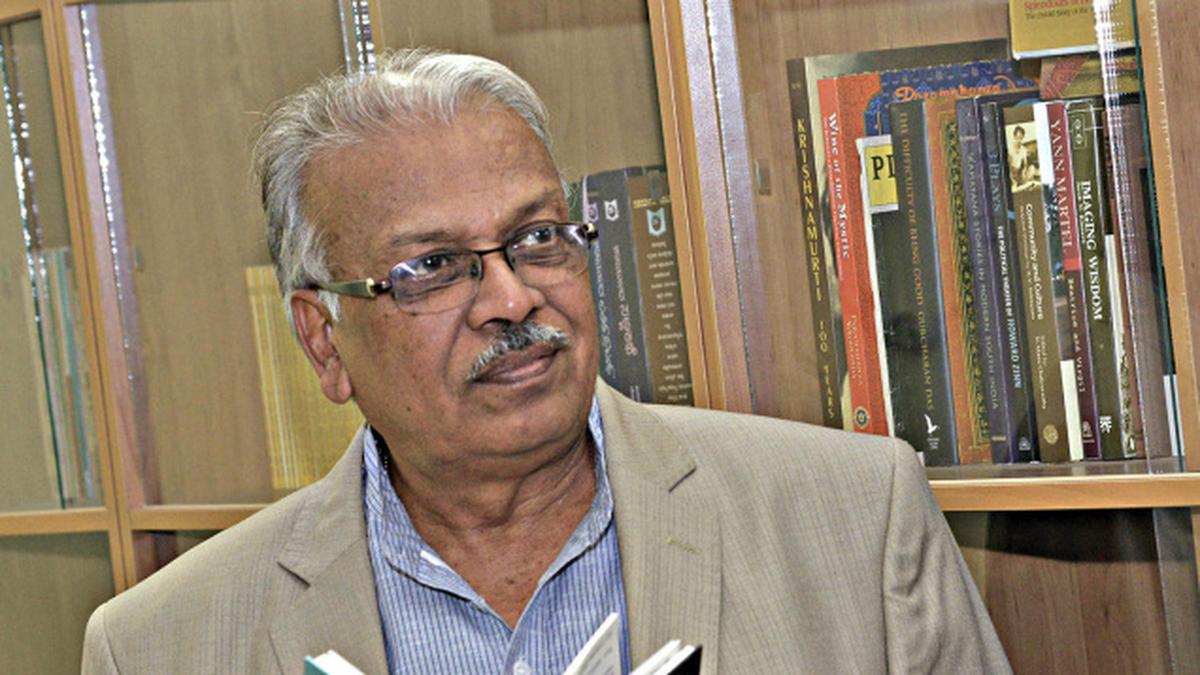

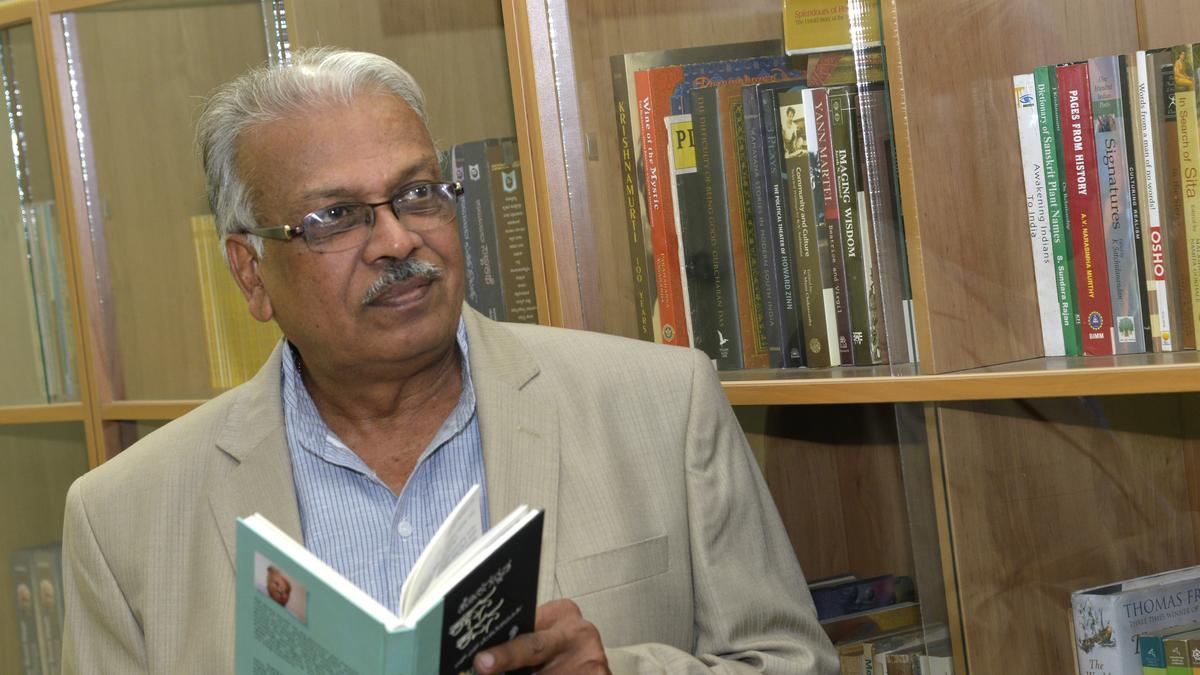

Muskan (holding her school certificates) with her mother and sister at home.

| Photo Credit:

R.V. Moorthy

Muskan, 19, is one of Bashri and Jarsheed’s daughters. Two years ago, she scored 450/500, with a 95% in Hindi in the Class 12 board exams. “I wanted to study further, but my father didn’t allow it. All my friends go to college; all my sisters studied only up to Class 8,” says Muskan, looking down when she talks, almost in a whisper. “I wanted to become a Hindi teacher, but my father never allowed it,” she adds, her face turning red.

Jarsheed, in his Mewati dialect, says, “Why should daughters study? They will get married, leave, and their husbands won’t allow them to work. So what’s the point?” While Jarsheed talks, his daughters neither interrupt nor argue. Bashri, who has never seen a classroom in her life, says, “My husband’s thinking is problematic. Had we educated Muskan, she would have become an earning member and would have been able to help our family.” Muskan shows off her laminated degree, then puts it back in her school bag she still treasures.

Low attendance in school

A few kilometres away from Sonkh village is the Government Model Sanskriti Senior Secondary School, the facade painted in the colours of the national flag. The school has adequate infrastructure to cater to students across age groups: a computer science laboratory, libraries, and a sports field. Yet, low attendance is a concern for the school.

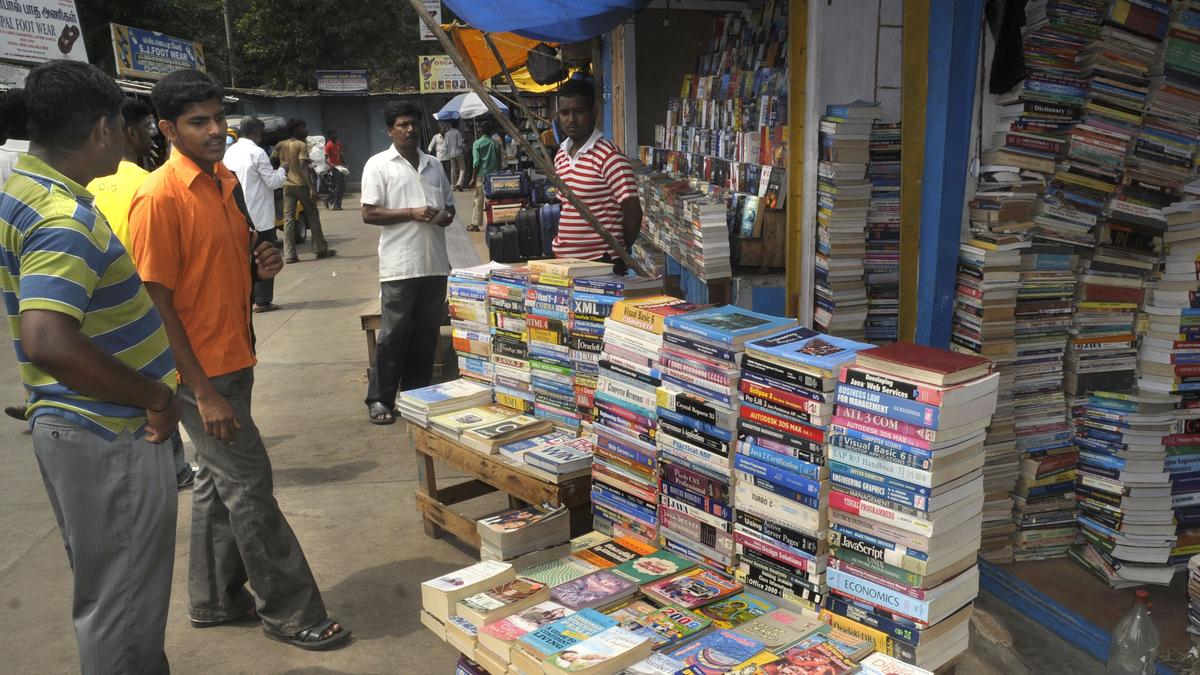

Students cut and clear the grass near the boundary wall of a government school in Nuh.

| Photo Credit:

R.V. MOORTHY

Manjeet Singh, who has been teaching here for six years now, explains that the recurrent problem in Nuh is either truancy (missing school) or absconding (have not attended for long durations). “Students get their names registered and then go missing, or some come to school and leave midway. This is a problem teachers face across Nuh,” Singh explains.

The school principal, Mukesh Kumar, has spent 29 years in the Mewat region teaching children. He says, “Most families send their children to school up to Class 12, so they can acquire a driving licence. Families aren’t comfortable with the idea of letting their daughters leave home to study.” He says children are trained to repair bikes or weld iron, so they are employable. “Not many come from families where education is discussed,” Kumar explains.

While the pass percentage in his school among Class 12 students was 59, for Class 10 students this was 47%. Kumar says, “The pass percentage went down because the Haryana government cracked down on the cheating menace.” Question papers are leaked at exam centres, or people scale walls to help with answers, or imposters appear for the examination, as per newspaper reports. Exams were cancelled at 10 centres this time, compared to 29 centres in the previous year. In 2023, the exams were cancelled at 40 centres, and a year earlier at 64 centres.

On February 27, the Class 12 English paper was leaked in Nuh and Palwal, minutes after the exam began. Outsiders reportedly took photos through windows and shared them online. At least four invigilators were dismissed.

The next day, the Class 10 Maths paper was leaked in Jhajjar and Nuh. While FIRs were filed, 25 police personnel, including four Deputy Superintendents of Police and three station house officers were suspended, and the HSEB Secretary replaced. Bhiwani, Jind, Jhajjar, Sonipat, and Nuh report cheating cases more frequently than other districts, say the police.

Nagpal says at least 226 flying squads were formed, and disciplinary action taken against 599 staff members. “The idea was to curb cheating. In 2022, at least 64 cases were registered. The next year 40 FIRs were registered, and in 2024, there were 29. This year at least 10 have been registered,” Nagpal says, adding that police were stationed on the rooftops of exam centres and houses nearby to get a bird’s-eye view. It’s often the crowd outside that aids cheating, he adds.

A systemic challenge

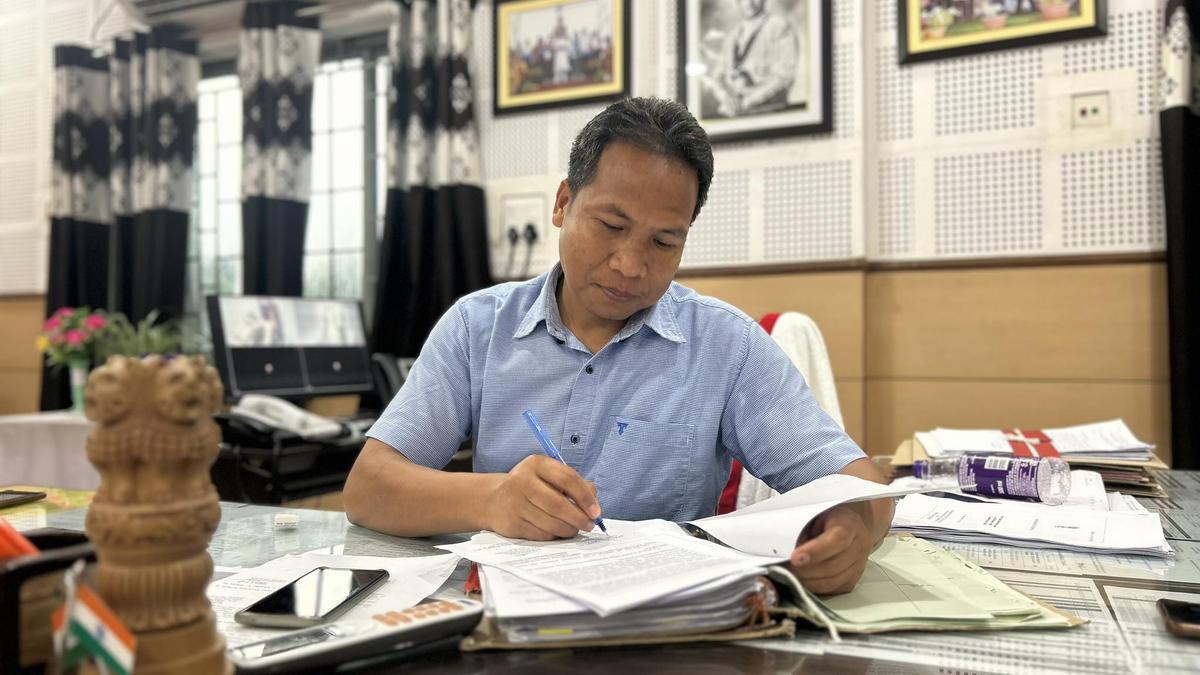

Deputy Commissioner of Nuh Vishram Kumar Meena acknowledges the multiple challenges the district administration has. He says they will now work on ways to improve the system. “Cheating has become a ‘cultural phenomenon’ or a ‘trend’. Almost everyone has become accustomed to the idea. The issue is so deep-rooted that when the Haryana government began to ‘dismantle’ the ‘system’, students dropped out of government schools,” he says. Then they would take admission in Open Learning centres (flexible attendance), where they bribed government officials, Meena adds.

In 2023-2024, at least 4,446 students from Classes 1-8 dropped out of school, as per data from the Education Department. Meena also shares an instance where one of the Open Learning centres in Nuh conducted an examination and found at least 34 imposters appearing on behalf of other people. “Now that we are curbing the cheating menace, it’s important to instil the idea of consequences in the minds of people, so they don’t repeat this behaviour.”

Meena talks about education as a part of a larger social structure. There aren’t that many job opportunities in Nuh, and larger families feel forced to pick the boy child who performs well in school to continue education. So, the other children drop out. If they are boys, they begin working; if they are girls, they are married off. He emphasises that rather than blaming the people or the administration, “there are systemic challenges that we need to tackle”.

A school for her

Meena says the district has a 22-25% shortage of teachers at both the primary and secondary levels. Teachers in Nuh also explain how the sarpanches, or village heads, haven’t promoted the culture of education in their villages. Meena says, “Out of 325 sarpanches, we have terminated 12 and are conducting inquiries on 50 others for forged and questionable degrees.”

In 2022, the Mewat Development Agency that looks after socio-economic growth, started working with nonprofits and began recruiting Shiksha Sahayaks or Teaching Assistants. Newly graduated teachers are paid a monthly salary of ₹17,000.

In Nalhar, Sakina, 40, squats on a cement floor to wash clothes. She uses stones to beat the grime out, under a hand pump. It is sunny, and she is sweating. Sakina dismisses a question around what she dreams of for her three daughters and a son, and goes back to washing her clothes. Two minutes later, in the Mewati dialect, characterised by the harsh sounds of the surrounding landscape, she says, “Who is bothered by what their children will do? Daughters will graze the cows and sons will become drivers. In our culture, women don’t study. What is the need to?” For a fleeting second, her daughters pause their work.

Edited by Sunalini Mathew

Published – May 30, 2025 12:57 am IST