Over six heady months of 1971, Indian cricket threw away the shackles of infancy that had held her prisoner for four decades, and stepped decisively into adulthood.

During that period, the team strung together two epochal series victories, first over the mighty West Indies, and then India’s colonial master of yore, England. These were more than just cricketing wins. Together, they laid the foundations of self-belief that would change the trajectory of Indian cricket in the years to come.

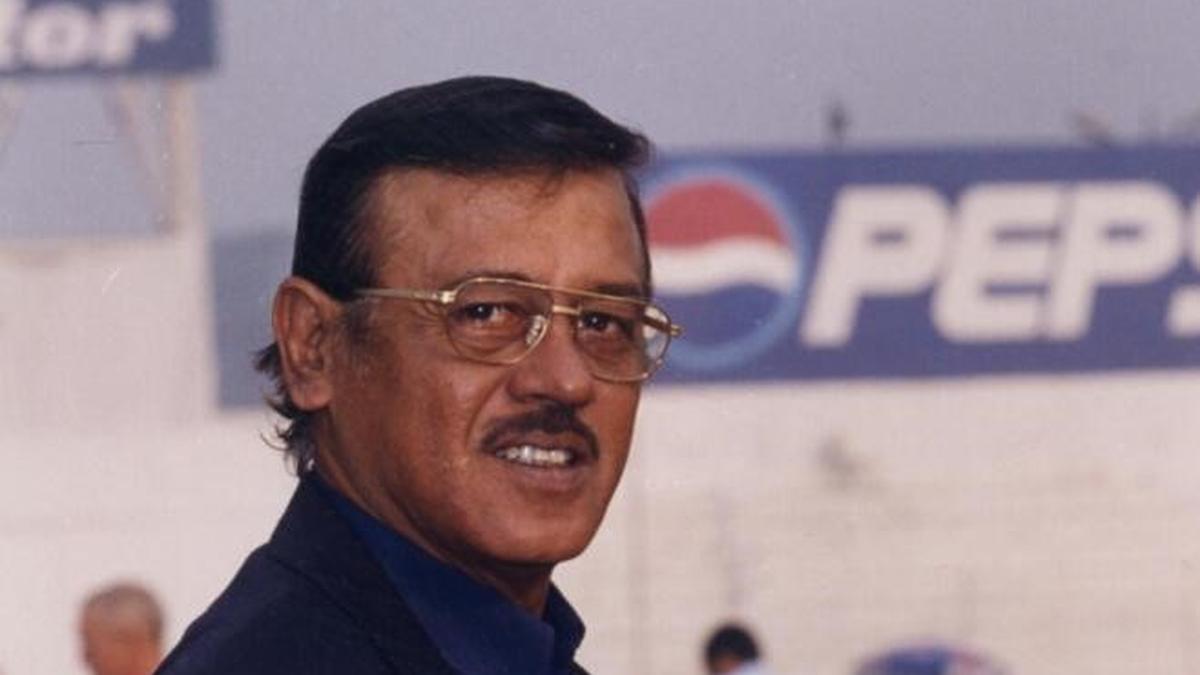

Among the heroes of those two sporting wars, was an extraordinary man who had turned his disability into a deadly deliverer of sporting destruction. His name was Bhagwat ‘Chandra’ Chandrasekhar, and his unlikely weapon, a polio-impacted arm.

ALSO READ | Paddy Shivalkar: Indian spin’s eternal handmaiden, a cricketer by accident

And yet, difficult as it may be to comprehend today, but for pressure from Indian fans and media alike, and a concatenation of circumstances, Chandra, already considered one of India’s great match winners by then, may never have travelled to England.

Silencing the Calypso

In fact, when India traveled to West Indies at the beginning of the year, Chandra’s name was missing from the squad. In a regional balancing act, given the fact that the West and South Zone dominated at the time, Srinivas Venkataraghavan, who had not been a regular member of the Indian XI under Tiger Pataudi, was appointed new captain Ajit Wadekar’s vice-captain.

Senior off-spinner Erapalli Prasanna, Mysore’s Ranji Trophy-winning captain and the world’s leading exponent of his craft at the time, was in the team, but clearly could not take his place for granted. The mercurial genius, Salim Durani, earned a recall into the team. Bishan Singh Bedi completed the spin attack around which the team revolved.

The inclusion of Chandra, the world’s most feared leg-spinner, and a man who was in excellent domestic form despite making a comeback from injury and a horrific road accident, had been vetoed by Vijay Merchant, the chairman of selectors who did not like ‘unorthodox’ cricketers. With Venkataraghavan’s elevation to vice-captaincy and exactly half the squad hailing from their region, the South Zone lobby had not pressed the point.

Thanks to the emergence of a young batting prodigy named Sunil Gavaskar, outstanding performances from veteran Dilip Sardesai, and a couple of match-winning wickets at a critical phase from Durani, India won one Test and the series. The margin may have been slender, but the Calypso had been silenced.

It was, however, not lost on either the fans, media and indeed the selectors themselves, that India had badly missed the services of Chandra in West Indies.

England: The Final Frontier

By the time the summer of 1971 came around, Merchant, under intense pressure, had agreed to include Chandra in the touring side to England. The leggie would be replacing Durani, who had had a forgettable West Indies tour other than his match-winning spell at Trinidad.

Having had his hands forced, Merchant issued a post-selection warning, deeming Chandra’s inclusion ‘a risk’. It was destined to go down in cricketing folklore as a monumental lack of foresight, much as his casting vote gift of captaincy to Wadekar over Pataudi before the West Indies tour, was to be deemed a stroke of genius.

As the sun broke through the clouds on a warm August day, India prepared to face off against the host for the last time that year. Neither team had managed that one crucial Test win through the long summer.

India may have been coming off a series win against West Indies, but England’s captain, Ray Illingworth, had an unbeaten record as captain after 19 Tests at the helm. Having won the toss, knowing it was a pitch that would be wearing by the time India batted, Illingworth’s confidence was unsurprisingly high.

In contrast, Chandra was a bundle of nerves. “This was a very important series for me as I was making a comeback after four long years and had been left out of the West Indies tour for reasons not known to me,” Chandra tells me.

“I had been inconsistent in the Tests in England but had been getting wickets in the county matches. So, before the Oval Test I had no clue whether I was playing despite having taken seven wickets in the match against Notts just before the Test.”

Getting dropped now would have been a severe blow to his confidence. Even worse, as Chandra admits, “I had to do well otherwise my cricketing career may have ended at that particular time.”

It was manager Hemu Adhikari who impressed upon Wadekar the importance of retaining the unpredictability of the leg-spinner in the arsenal at the Oval, making one of those calls that smack of genius when they come off. Chandra would pay back the faith in full measure.

On Day 4, England came out to bat for the second time, enjoying a 71-run lead. After a few overs of perfunctory medium pace, Chandra was given the ball. He was always going to be a handful on the fourth-day pitch, and Wadekar knew this. Chandra recalls, “Ajit had confidence in me and gave me the ball after three overs.”

Chandra got India the first breakthrough… as a fielder. He talks me through what happened when Brian Luckhurst drove a ball back at him hard: “I thrust my right hand out, the ball came at tremendous speed and my hand didn’t get there fast enough to stop the ball, just enough for a single finger to touch and deviate it. The ball smashed onto the non-striker’s stumps, leaving John Jameson, who had scored 82 in the first innings, stranded a couple of inches outside his crease.”

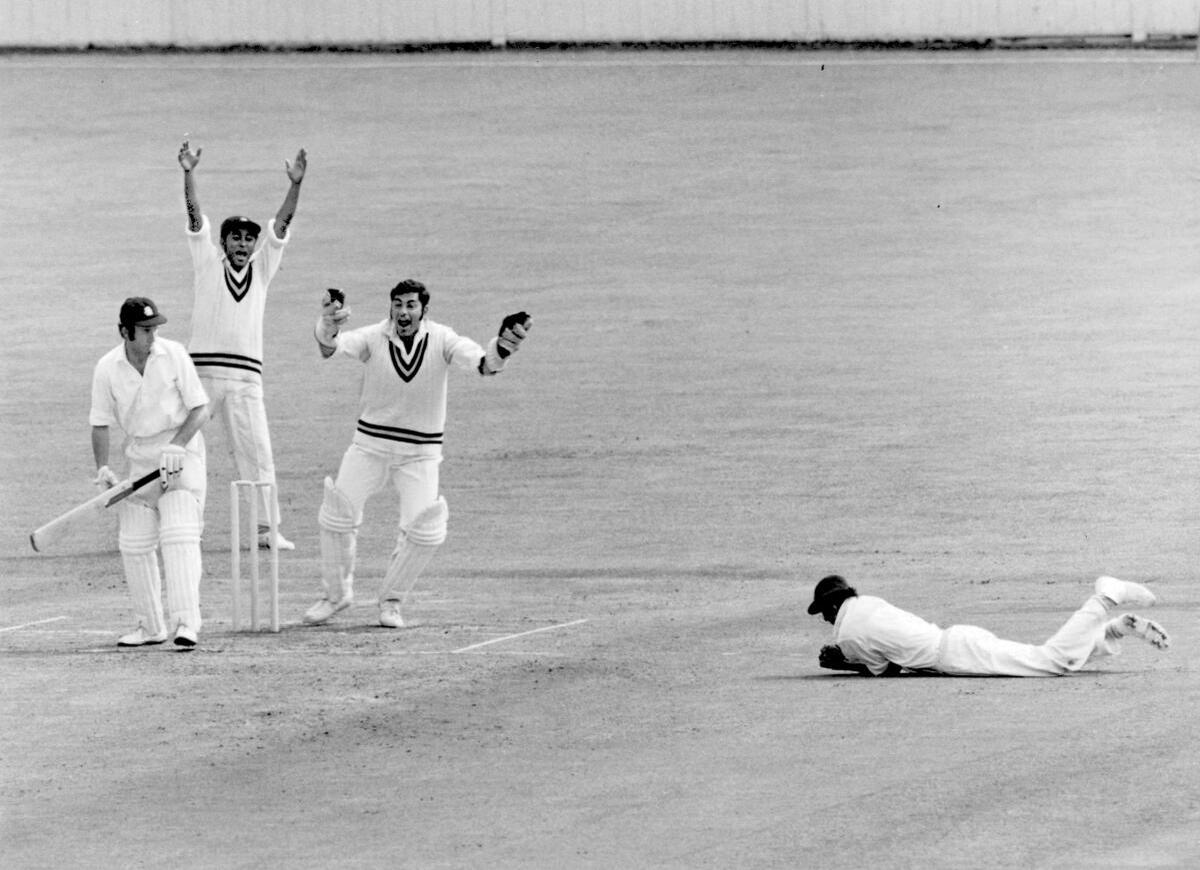

Keith Fletcher is caught by E.D. Solkar off Chandrasekhar for a duck, during England’s second innings in the Third Test at Oval on August 23, 1971. The wicketkeeper is Farokh Engineer and at slips is Dilip Sardesai.

| Photo Credit:

Central Press Photos, London

Keith Fletcher is caught by E.D. Solkar off Chandrasekhar for a duck, during England’s second innings in the Third Test at Oval on August 23, 1971. The wicketkeeper is Farokh Engineer and at slips is Dilip Sardesai.

| Photo Credit:

Central Press Photos, London

John Edrich walked in. Generally, Chandra did not plan his dismissals, preferring to bowl in the right areas and letting his speed, spin and variations create the chances. But this time he did.

“I wanted to bowl a googly but my plan had to be changed,” he says. “At that time Dilip Sardesai and I used to track the races and there was this fast horse called Mill Reef (it had just won the Epsom Derby that summer, coming from behind with a sensational burst of speed). So, as I was about to run in and bowl, Dilip from the slips shouted, ‘Chandra ek Mill Reef dalo’ (bowl a Mill Reef). I understood and instead of a googly, bowled a faster one, and before Edrich brought his bat down, his stumps went cartwheeling.”

Over the next couple of hours, Chandra was unplayable at one end, picking up wickets at regular intervals, with Venkataraghavan frustrating batters at the other with his metronomic accuracy. When John Price was trapped leg-before by a Chandra top-spinner, England had been dismissed for 101. India was left to score 173 runs for a historic victory, the closest they had come since 1932. Chandra’s figures read a remarkable 18.1-3-38-6.

When Abid Ali scored the winning runs, cricket’s final frontier for the Indian team, beating England in England, had been achieved. What was remarkable about this was not the victory itself, but the fact that it was thanks in no small measure to an unlikely ‘spin strategy’ formulated by a one-eyed captain, nurtured by his astute successor and executed by a group of wizards of spin, led by a twirlyman with a polio-stricken bowling arm.

Chandra would go on to have a remarkable career, delivering crucial breakthroughs and remarkable victories time and again, gathering 242 Test wickets between 1964 and 1979, fully deserving of his status as one of India’s greatest match-winners.

When I called to wish him on his 80th birthday today, in response to my question about how he is celebrating, he smiled and replied with one word—quietly. Enjoy your time at home in Bengaluru with family and friends today, Chandra, and thank you for the memories.