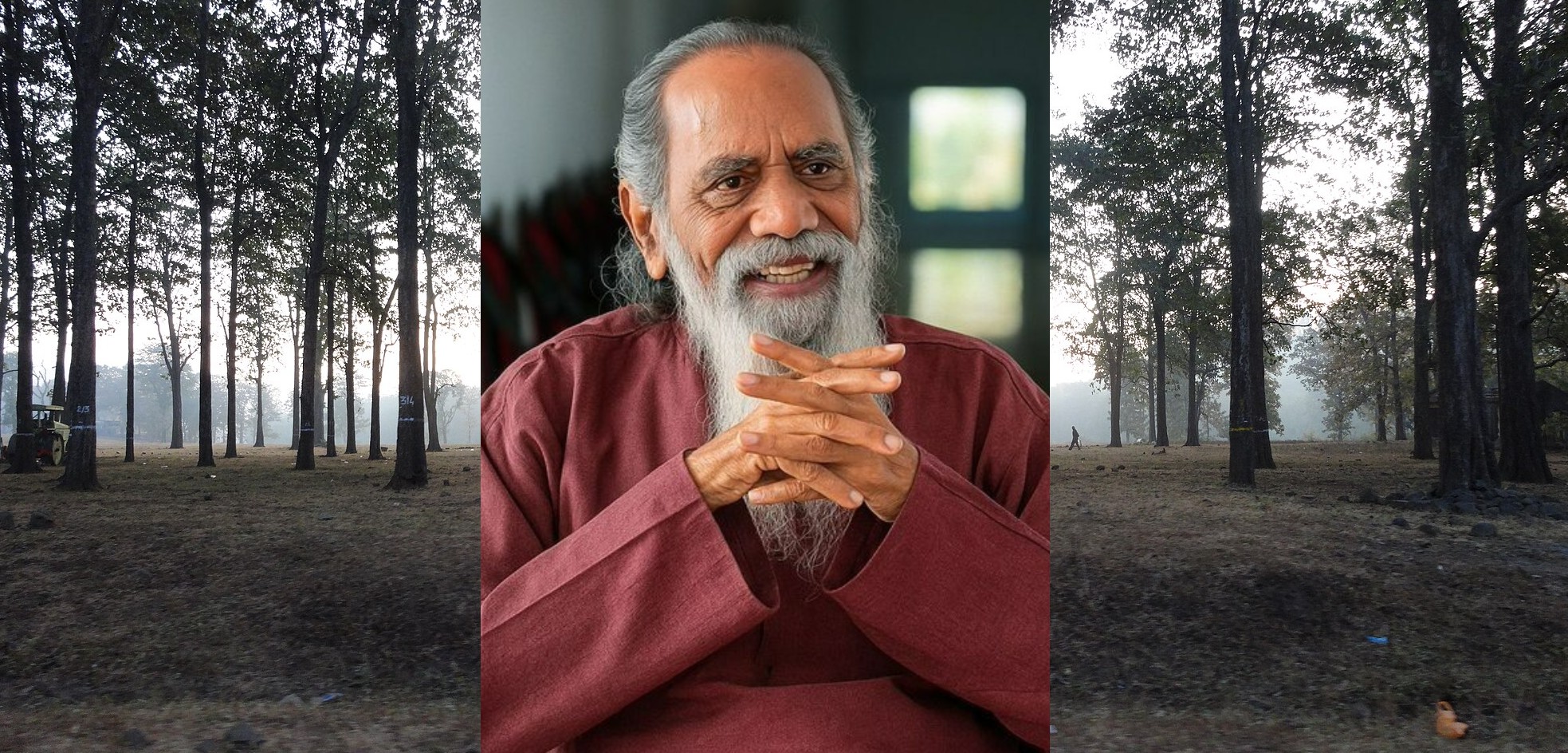

- Farmers in Jharkhand, who have started planting on barren land under the Birsa Harit Gram Yojana scheme, will receive carbon finance funds in the next few months. The aim of granting funds is to help them maintain their plantations.

- At present, more than 30,000 beneficiaries are associated with the carbon finance scheme being implemented in 18 districts. There is a plan to add 125,000 beneficiaries.

- Experts emphasise on linking more farmers to this scheme as well as periodic monitoring of all such schemes. They also consider it crucial to create a system to preserve trees after the end of project tenure.

Last year, while countries and organisations from across the world gathered in Azerbaijan’s capital Baku for COP29 and discussed carbon trading rules, about 3,800 km away, farmers living in Jharkhand were excited on learning that they would receive carbon finance funds in a few months.

Farmers in Childari village in Bedo block of Ranchi, famous for peas and other vegetables, have chosen to avail the benefits of carbon finance — financial resources like loans, investments and subsidies given to acquire greenhouse gas emission allowances. Carbon financing will be done through growing fruit-bearing trees under the Birsa Harit Gram Yojana (BHGY) — a state government scheme that aims to conserve barren land and make it cultivable to amplify livelihoods.

According to the Economic Survey of Jharkhand (2023-24), the BHGY scheme has been running since 2016-17 under MNREGA with an aim to increase employment opportunities in the state. Under this scheme, 135,122 farmers have planted mango and other fruit-bearing trees in 1,16,637 acres. Eligible farmers with a maximum of one acre of land are provided with financial help as well as assistance for five years. It is estimated that thanks to the scheme, each family has managed to earn profits of more than ₹50,000 annually.

There, however, was a catch. It wasn’t clear how marginal farmers would continue maintaining their plantations after five years. To overcome this problem, the BHGY scheme has been linked to the carbon finance scheme, which will provide additional income to the beneficiaries for the next 20 years.

Additional livelihoods

Mongabay visited Childari village and spoke to the beneficiaries of the BHGY scheme. Beneficiary Namita Devi said she came to know about the initiative through the Rural Development Department of the Jharkhand government, promoted by Transform Rural India Foundation (TRIF) and Intellecap Advisory Services.

The beneficiaries said they were a bit hesitant before joining the scheme. The fact that they were told to share their bank details and were made to sign digitally made them suspicious.

“We were not very keen initially because of past experiences. Then we consulted with the head of the panchayat and he explained to us about carbon finance. After this, many people from the village agreed to join it,” said Namita Devi.

Elaborating on past experiences, Raju, another resident, said, “In Nihalu Kaparia, our panchayat, biometrics of some people was done in the name of renewing gas connections. After this, money was withdrawn from their accounts illegally. People are a bit scared after that incident.”

Namita Devi planted 112 mango trees on her fallow land in 2021-22 with the help of the Jharkhand government. The trees are still small, but in the last season, she sold mangoes worth ₹8,000-10,000. Namita, who joined the carbon finance scheme in 2024, says that the amount of carbon her trees have absorbed will be assessed through satellite surveys. On this basis, she will continue to be paid every year for the next 20 years.

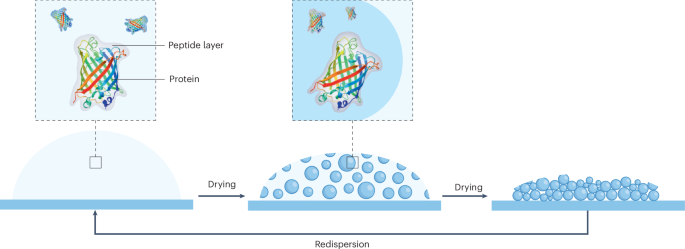

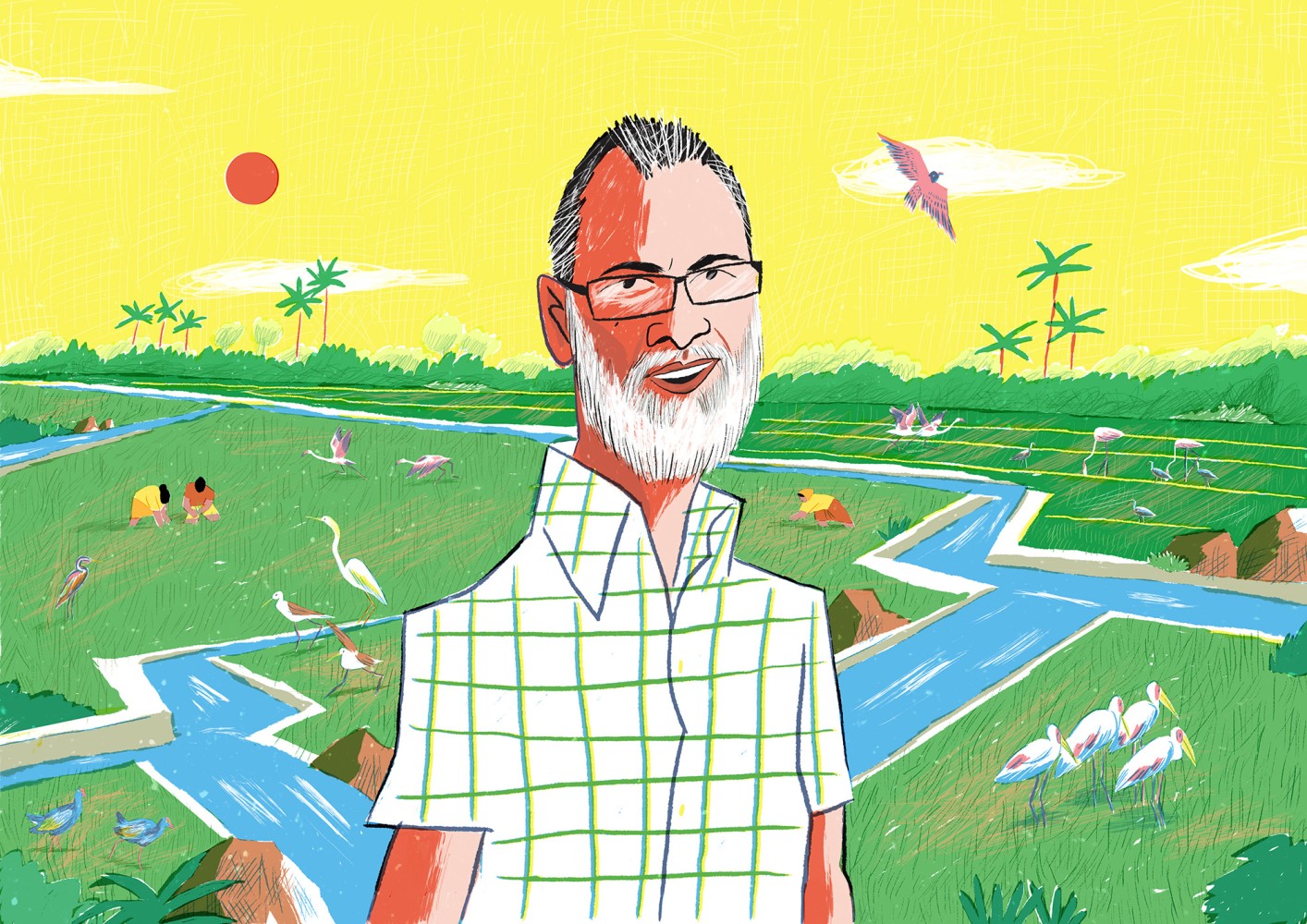

TRIF Director Ashok Kumar told Mongabay, “The aim of BHGY is to enable people to earn money and have a permanent source of livelihood. Beneficiaries can plant on their fallow land. In the one acre model, 112 fruit and 80 timber trees are planted.”

Ruth Khes, who planted trees on her barren land under BHGY, says carbon finance is a good scheme. She told Mongabay, “First, the beneficiaries are getting additional income. Second, it’s keeping the environment clean. Farmers are also getting motivated to plant more and more trees. When they will start getting money, they will be more involved in the process.”

The Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare has prepared a framework for promoting a Voluntary Carbon Market (VCM) for the agriculture sector in India to encourage small and marginal farmers to avail carbon credits. For this, the Carbon Credit Trading Scheme was notified in December 2023. The government believes that introducing farmers to the carbon market can increase their income as well as accelerate environmentally friendly agricultural practices.

Agriculture is one of the sectors selected under the offset mechanism of carbon trading in India. Through this scheme, entities/farmers can register projects related to reducing greenhouse gases for the issuance of Carbon Credit Certificates (CCU).

Geeta Devi told Mongabay that the farmers who missed out on this scheme earlier want to join it now. She says that as the trees grow or get older, higher payments are made directly to the beneficiary’s account.

She adds that the measurement of orchards will be initiated soon, following which farmers will get paid as per CCU credit.

How it works

Under the BHGY scheme, those who have been planting on one acre of fallow land since 2018 can apply for carbon finance. Each farmer will receive an additional income of ₹60,000 in the next 20 years from carbon finance.

The scheme is currently active in 18 districts. So far, more than 30,000 beneficiaries have taken advantage of the scheme. The first instalment is likely to be credited to the beneficiaries’ accounts by July-August this year. There is a plan to connect about 125,000 (1.25 lakh) beneficiaries with carbon finance in the next year.

The funds required for this scheme are being provided by Rabo Bank (Co-operative Bank of Netherlands). Its accounting process is being completed by ACORN. At the same time, the responsibility of implementing it on the ground is jointly on TRIF and Intellecap India.

First, an agreement is signed with beneficiaries. They are registered on the portal created by ACORN. After this, polygon mapping of the plot is done. All the plants will be included under geo-coordinates. This process will be monitored through a satellite programme called sat-intelligence.

There will mainly be two indicators — the thickness of the tree trunk, and tree cover. This will determine how much carbon a particular tree has absorbed. The calculation is done with the help of technology and there is no human intervention in it. As soon as it is calculated, Carbon Removal Unit (CRU) will be credited to the beneficiary’s account. On the basis of this unit, funds will be deposited.

TRIF joint director Karimuddin Malik told Mongabay, “If we talk about the rate of carbon finance, then every portal has different rates. But, currently on ACORN’s portal, the price of one CRU is 35 to 40 Euros. The price of Euros will be taken on the day of payment. Eighty percent of the payment will be credited directly to the farmers’ account.”

Experts say that this initiative will increase the income of marginal farmers which will help in better maintenance of horticulture. They say that with increased production, a supply chain of fruits can be created and industries making food items can be developed. There is a possibility that the Mallika variety of mango will have a bumper yield. Then it can also be exported. This will ensure better income for the farmers.

Anurag Dhir, Associate Consultant, Intellecap Advisory Services, which provides consulting services in the field of climate and energy, says: “Small farmers are most affected by climate change. Due to crop loss, they get stuck in a debt trap. Therefore, our aim is that firstly, farmers get additional income through carbon finance. Second, they should have their own property and be able to earn from it even when there is no rain.”

Why are carbon markets needed?

Like the rest of the world, the carbon finance market in India is also slowly taking shape. According to a media report, on October 23 last year, the carbon finance market was established in eight states — Uttar Pradesh, Haryana, Punjab, Maharashtra, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh and 80,000 marginal farmers of Telangana are also going to get carbon credit money for the first time. These farmers grow paddy, cotton, wheat, maize, sugarcane etc. in about 40,000 hectares.

The Government of India has also created the Indian Carbon Market (ICM) by notifying the Carbon Credit Trading Scheme (CCTS) in June last year. Under this, a framework and outline has been prepared for carbon trading in the country.

Vaibhav Chaturvedi, senior fellow at the Council on Energy, Environment, and Water, tells Mongabay, “Some big companies are working in the carbon market in India. We did not put a price on carbon until now, but it’s happening. The aim of the Indian government is also to take advantage of the carbon absorbing capacity of agriculture, forestry and other things.

The voluntary carbon market was expected to reach $3 billion by the end of 2024. Research suggests the market will grow further to between $10 billion and $40 billion by 2030.

However, experts say that this scheme is in the interest of small farmers, and suggest paying attention to the details. They say that it is a bit difficult for farmers to understand the legal language of the agreement.

Subrata Chakraborty of the World Resource Institute (WRI) tells Mongabay, “So far, in the accounting of carbon credits, most of it goes to the project developer. In this context, this scheme is a good initiative. If this income reaches the farmers, they will definitely get some relief in case of crop failure due to drought.”

It is a voluntary scheme to reduce greenhouse gases worldwide. Carbon credits from farmers can be purchased by industries such as aviation, mining or fertilisers and cannot reduce their carbon emissions due to the nature of their business.

However, what is important in the scheme is how the CCU is sold.

Chakraborty says, “If it is sold in the European market, then an Emission Reduction Purchase Agreement will be made by contacting an organisation there. In this, the buyer is promised to sell a fixed quantity every year and the income is determined by the fixed volume. Second, there is the spot market where prices keep changing. In this, you give information about the carbon credits generated to all the companies. Then the prices are fixed with them.”

The income of farmers has also decreased due to the rapid decline in the average size of land holdings across India including Jharkhand. It decreased from 2.28 hectares in 1970-71 to 1.84 hectares in 1980-81, 1.41 hectares in 1995-96 and 1.08 hectares in 2015-16. On the other hand, the number of marginal farmers has increased in Jharkhand. In the year 2010-11, the number of marginal farmers was 1,848,000. Whereas, in 2015-16, this figure increased by 6.13% to 1,962,000. During this period, the land area owned by marginal farmers decreased from 764,000 hectares to 754,000 hectares. More than 70% of the farmers in the state are marginal. Almost half of the farmers have less than 0.4 hectares of land.

In Jharkhand, farming is done on about 18 lakh hectares which is less than one-fourth of the total area of the state. The irrigated land in the state is only 1.6 lakh hectares which is 9.3% of the cultivated area. Therefore, the cropping intensity here is 126%. In such a situation, it is very important to arrange for additional income for small farmers so that they can earn a living. Chakraborty says that this scheme can achieve this goal to some extent, but he emphasises on monitoring.

He says, “In the coming times, the private sector will also take forward such schemes in other ways. In such a situation, it will be very important to keep an eye on them. Governments will have to ensure that the rights of farmers are protected. Additionally, the government will also get an additional means to provide relief in this period of climate change.

At the same time, Chaturvedi emphasises on saving trees even after the project ends. He said, “The special thing about these schemes is that money will be given not on the basis of saplings planted, but on the basis of keeping them alive and their capacity to absorb carbon. Also, it is important to create a system to preserve trees instead of cutting them down after the project is over.”

Read more: Farmers demand separate minimum support price for natural farming products

This story was reported by Mongabay India’s Hindi team and first published here on our Hindi site on April 18, 2025.

Banner image: The aim of BHGY is to increase the income of marginal farmers. The scheme is linked to carbon finance so that farmers can take proper care of their orchards. Image by TRIF.