- Chhattisgarh, widely known as the ‘rice bowl of India’ has received government approval for several ethanol plants.

- The decision however, has triggered protests in several proposed locations, where local communities have voiced concerns over potential environmental pollution.

- Agriculture and food security experts have also cautioned that diverting food grains for fuel production could jeopardise the country’s long-term food security.

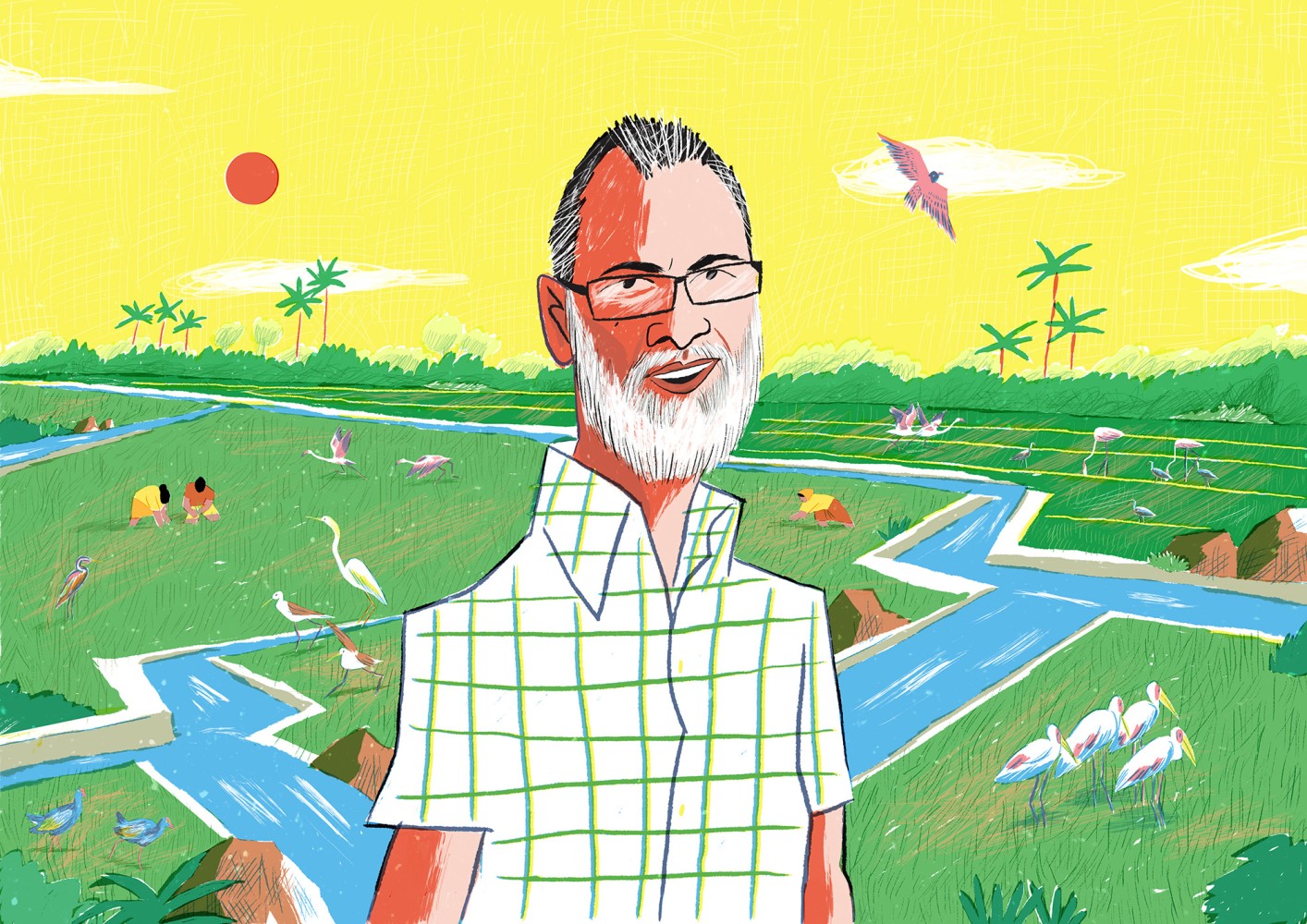

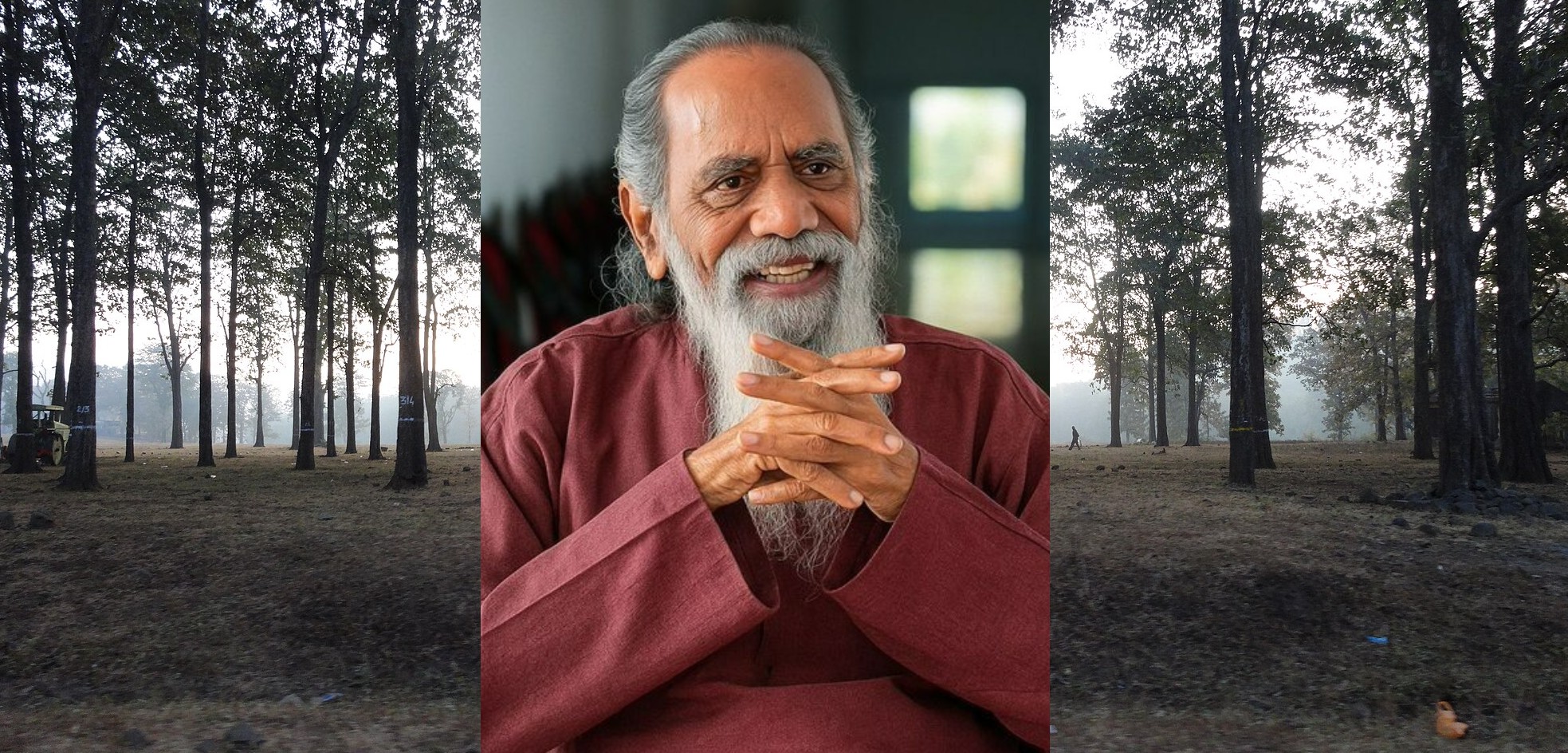

As the conversations around ethanol blending with petrol intensifies, Kumari Sahu reacts sharply whenever she hears the word ‘ethanol.’ Her worries are not about vehicle mileage but about the health of her family and the impact on the crops she grows.

Sahu resides in Patharra, a village in the Bemetara district of Chhattisgarh, where an ethanol plant commenced operations in 2024. She claims that the black, foul-smelling wastewater discharged from the plant has destroyed several of her paddy fields.

“I have three and a half acres of land. That’s what sustains my livelihood. But my paddy crop has completely failed,” she told Mongabay India. The problems extend beyond crop loss. “Because of the constant stench, it is difficult to find labourers or even work in my own fields. No one wants to step in because of the unbearable smell from the distillery.”

Her concerns are echoed across Patharra, a village of about 250 households. Residents say the stench has made life unbearable. At any time of day or night, a strong smell spreads through the village, forcing people to cover their faces with cloth.

Village residents fear that the wastewater discharged by the plant will eventually contaminate the groundwater. They have been protesting for over 10 months in many innovative ways. In October 2024, men shaved their heads. They have petitioned authorities, from the tehsildar to the Chief Minister, but claim their complaints are being ignored.

Chandan Sahu, a youth from the village, said, “Elderly people and women who were peacefully protesting were booked for causing public unrest and sent to jail. No one is hearing us. I don’t know how we are supposed to live with this stench and polluted water. If things continue like this, we’ll be forced to abandon our village someday.” In January 2025, police filed two separate FIRs against about 40 people from the village, including women.

Patharra is not the only village facing such problems. In Bemetara alone, 11 ethanol distilleries are planned, and protests are taking place in several locations.

In neighbouring Ranka village, the panchayat sarpanch, Ghanaram Nishad, has long been opposing an ethanol distillery being built on 35 acres. “We have already seen the condition of Patharra. We are not against ethanol distilleries. But if such a facility is built on agricultural land and near a village, it will bring disaster. The pollution has made life miserable for the people of Patharra. We won’t allow our village to become the next Patharra,” he said.

Gautam Bandopadhyay, convener of the Nadi Ghati Morcha and a well-known social activist, stated that much of the land acquired for these plants includes village commons, such as pastures, cremation grounds, and cowsheds, thereby undermining the rural economy. Despite opposition from village residents and environmentalists, no thorough scientific review has been carried out, he added.

The government, however, defends the industry. In first week of August, when farmers from Kondagaon raised concerns about pollution and crop damage, Agriculture Minister Ramvichar Netam who visited the village said, “We will develop a plan to compensate for any losses. The unit hasn’t even fully started yet; let it function. This is a new initiative for the state. It is a big opportunity for the farmers of this district, and not just this district, but for the whole state.”

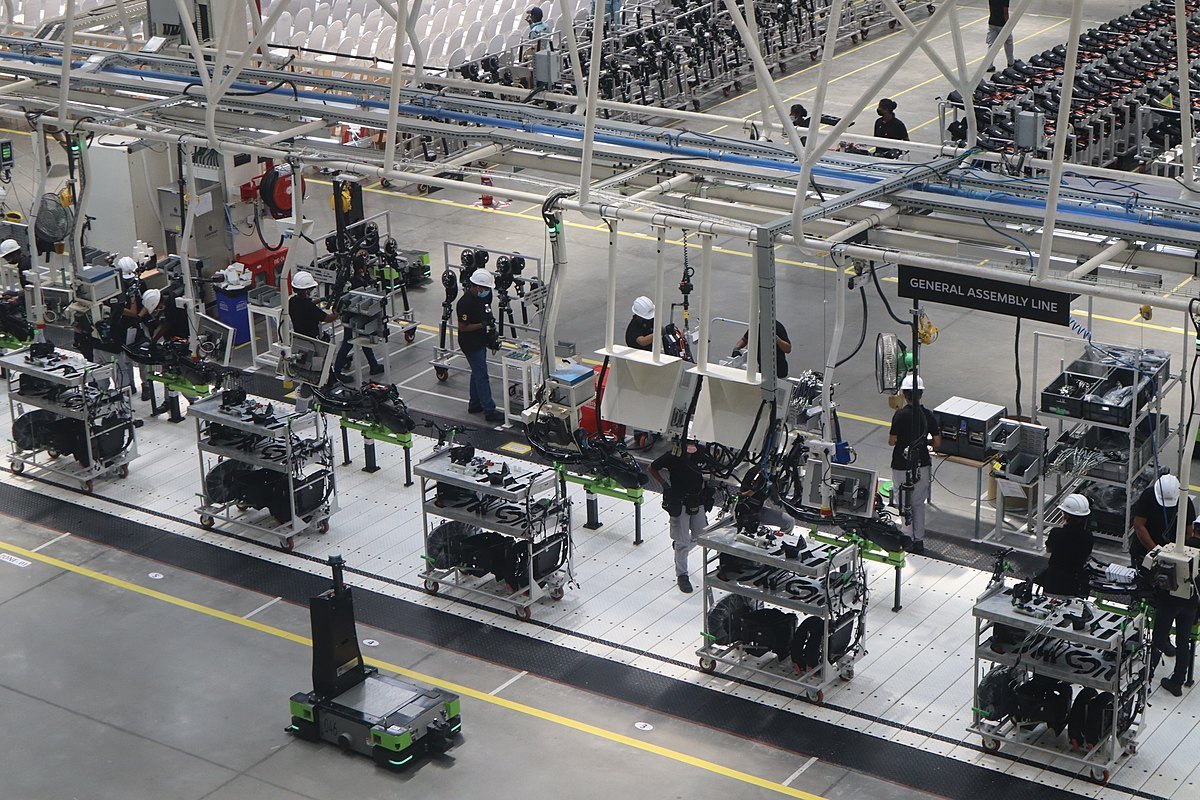

Ethanol push in Chhattisgarh

In the district of Kabirdham, an ethanol distillery was set up in September 2023 under a public–private partnership at a cost of ₹1.41 billion. The molasses-based plant, with a capacity of 80,000 litres per day, shut down within a year because of a shortage of raw material.

Although this unit was based on sugarcane, it illustrates the challenges ahead. The state government is aggressively pursuing ethanol production. In 2024, it informed the assembly that it had signed MoUs for 34 new ethanol distilleries across Chhattisgarh. A central government document notes that 42 plants have been approved in the state, of which majority are grain-based. The government states that production has already commenced at nine plants.

However, experts argue that in a state like Chhattisgarh, widely known as the rice bowl of India, setting up numerous ethanol plants may bring multiple complications. Bandopadhyay said that with many plants based on paddy and straw, food security may also be threatened as paddy cultivation is already under pressure nationwide.

For several years now, the Chhattisgarh government has been offering an additional bonus over the Minimum Support Price (MSP) announced by the central government for the procurement of paddy. While the central government has set the MSP at ₹2,183 per quintal for common paddy and ₹2,203 per quintal for A-grade paddy, the Chhattisgarh government procures paddy from farmers at the rate of ₹3,100 per quintal.

This additional price for paddy has already severely impacted crop diversification in the state. Year after year, farmers in Chhattisgarh are being incentivised to grow more paddy. The pace of paddy production can be understood from a single statistic: in 2009–10, paddy production in the state stood at 4.11 million tonnes, which more than doubled to 10.5 million tonnes by 2022–23.

A risky trade-off

Food and agriculture policy expert Devinder Sharma stated that diverting food grains into ethanol for fuel is a dreadful idea for a country that probably has the one of the largest populations of hungry people in the world. “At a time when a large population is unable to afford meals for a day, it is rather important to feed humans; cars can wait.”

Sharma pointed out that producing one kilogram of paddy in Chhattisgarh requires nearly 3,000 litres of water. Farmers are often blamed for overusing water, but the crop itself is highly water-intensive. Punjab faced a similar trajectory — paddy there needs around 5,000 litres per kg, and the state is now in the grip of a groundwater crisis, with many blocks declared “red zones”. He warned that Chhattisgarh could face the same fate, threatening both farming and drinking water.

“The same concerns apply to ethanol,” Sharma added. “When its ill effects will come to the fore, then I want to know who will take responsibility for it. Will any minister or scientist be held accountable? Unless accountability is fixed, the pattern will repeat, profits will go to some, while blame will fall on others. The government must also answer a crucial question, where will millions litres of water come from to make ethanol?,” he further adds.

Other experts share similar concerns. They argue that even the broken or lower-quality rice being diverted to ethanol is edible and is commonly used in mid-day meals, ration schemes, or exports.

Farmer leader Nand Kashyap of the Akhil Bhartiya Kisan Sabha said, “When India still ranks low on the Global Hunger Index, turning food into fuel could be a grave ethical and strategic error. Across the world, we’re seeing that as ethanol production increasingly relies on food grains, farmers are beginning to shift towards crops that fetch better prices as fuel, rather than food. This can lead to unstable market rates, price distortion in mandis, and food inflation.”

Alok Shukla, convener of the Chhattisgarh Bachao Andolan, added that incentivising paddy for ethanol could prove ecologically disastrous. “When the country is struggling to feed its people, burning food for fuel is not a sustainable path. States like Chhattisgarh must decide: should we sacrifice food security and groundwater for the sake of meeting climate goals? And has ‘development’ now become synonymous with industrial expansion, even if it crushes agriculture and farmers beneath it?”

Read more: Chhattisgarh tribal body says consent for mining in Hasdeo Arand was forged

Banner image: Kumari Sahu from Patharra, a village in Chhattisgarh’s Bemetara district shares concerns about the ethanol plant. Image by Ayushi Sharma/Mongabay.