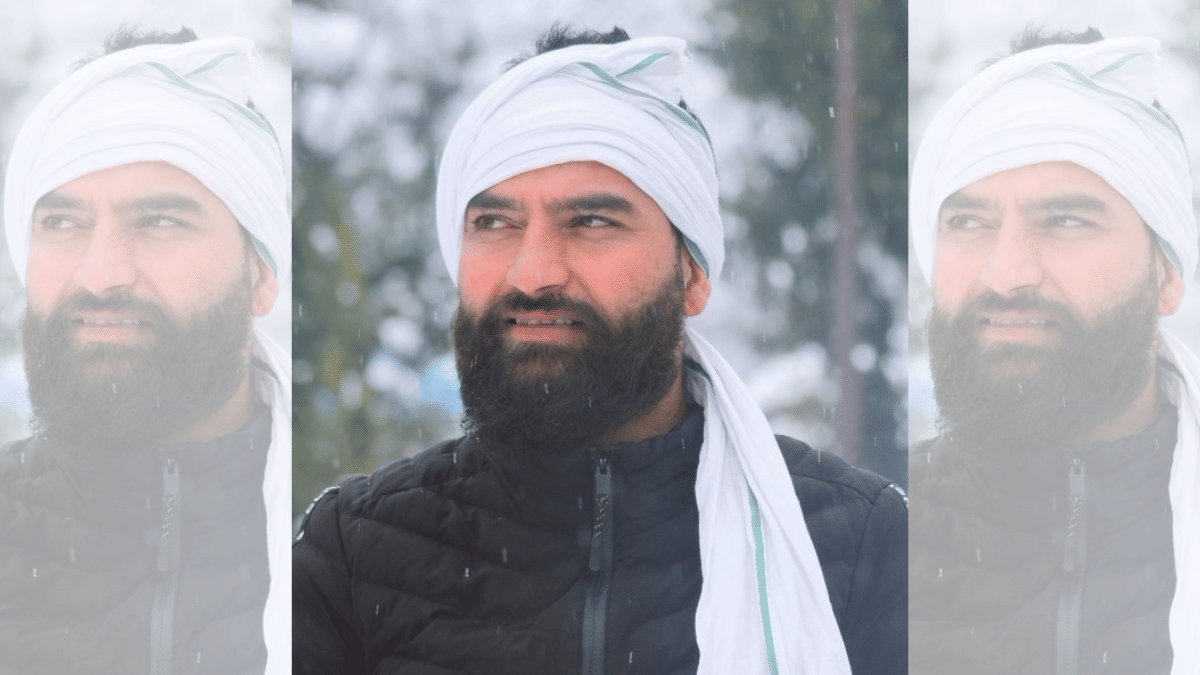

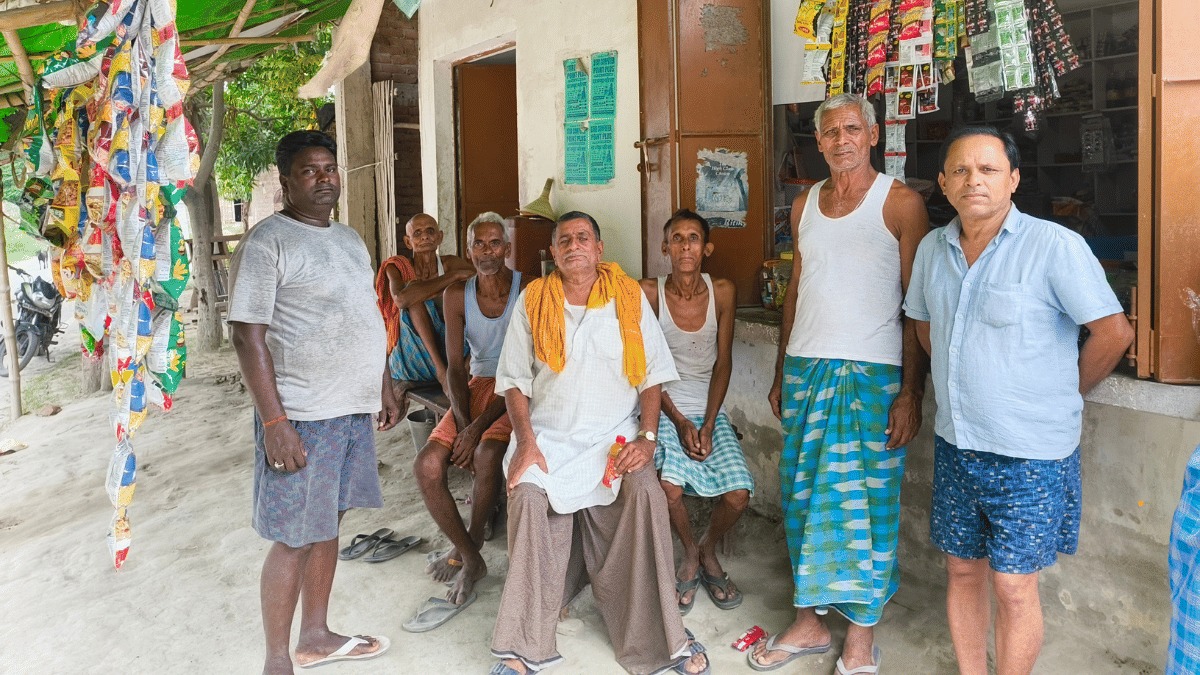

On an evening in a village dalan, an old uncle, who proudly says he has voted in more than seven or eight Bihar assembly elections, smiled and said with quiet certainty: “Ye Chanakya nahi, Chanakyon ki dharti hai. Yahan jo bhi Chanakya banane aata hai, Bihar usko thanda kar deta hai”(This is not just the land of Chanakya, it is the land of many Chanakyas. Whoever comes here trying to play Chanakya, Bihar cools him down).

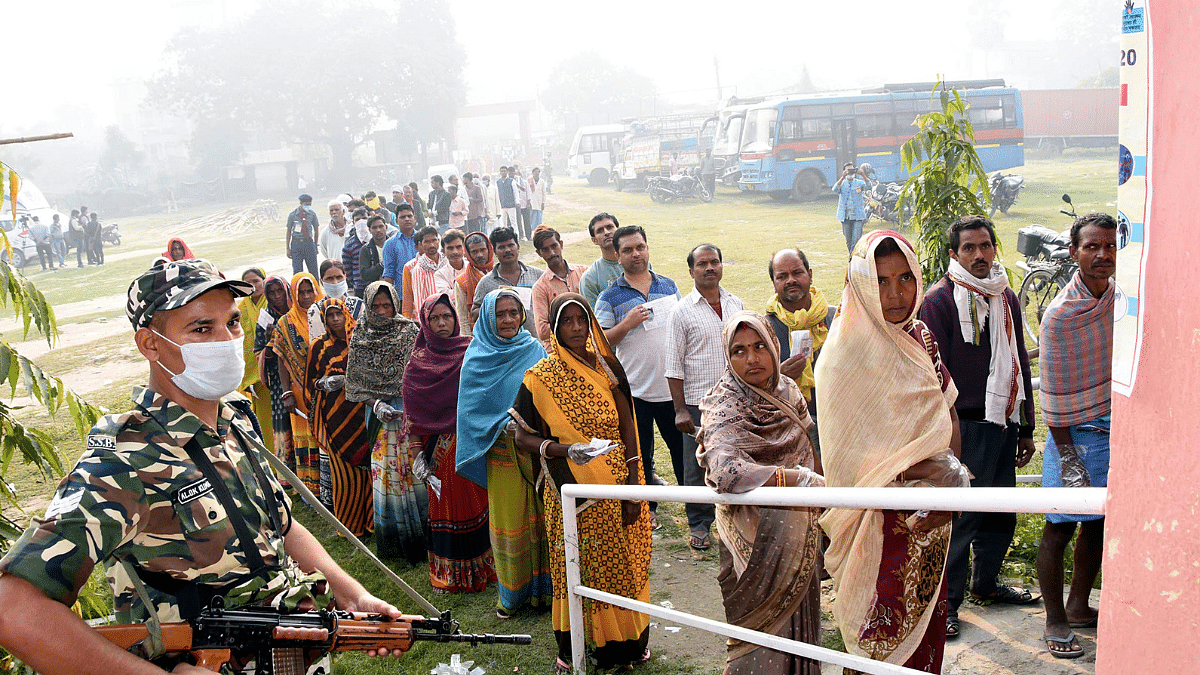

That remark carries the wisdom of decades. Bihar has always humbled political tacticians who thought they had mastered its complexities. The Assembly election of 2025 is a reminder of that unpredictability. It may well be the most decisive contest since 1990, when Lalu Prasad Yadav brought the Congress era to an end and set off the Mandal revolution. That election reshaped caste politics, gave new meaning to the idea of samajik nyay, and left a deep imprint on the political vocabulary of India. Every contest since has unfolded in its shadow. Today Bihar stands on the verge of another tectonic shift.

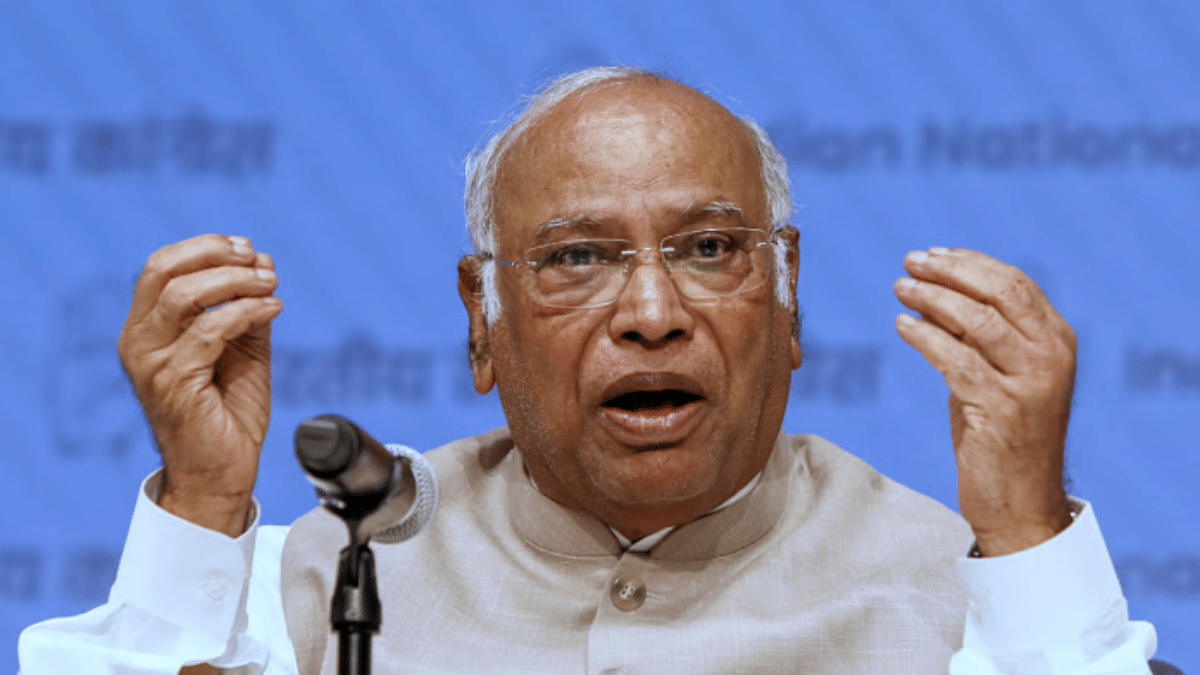

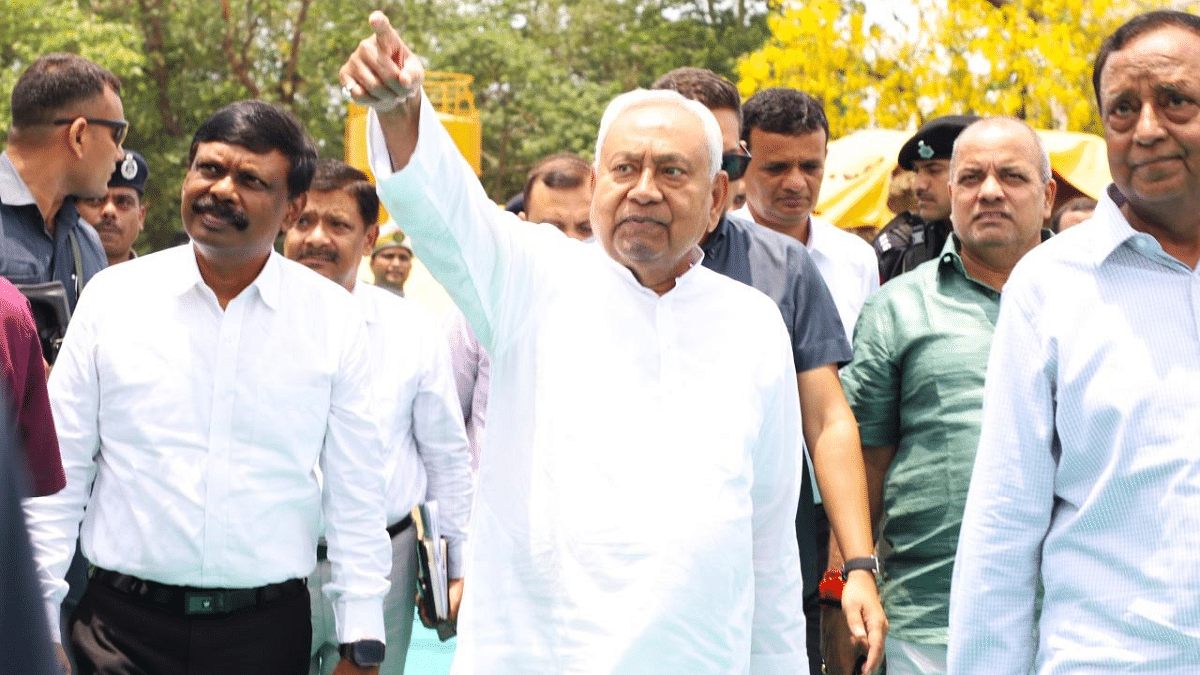

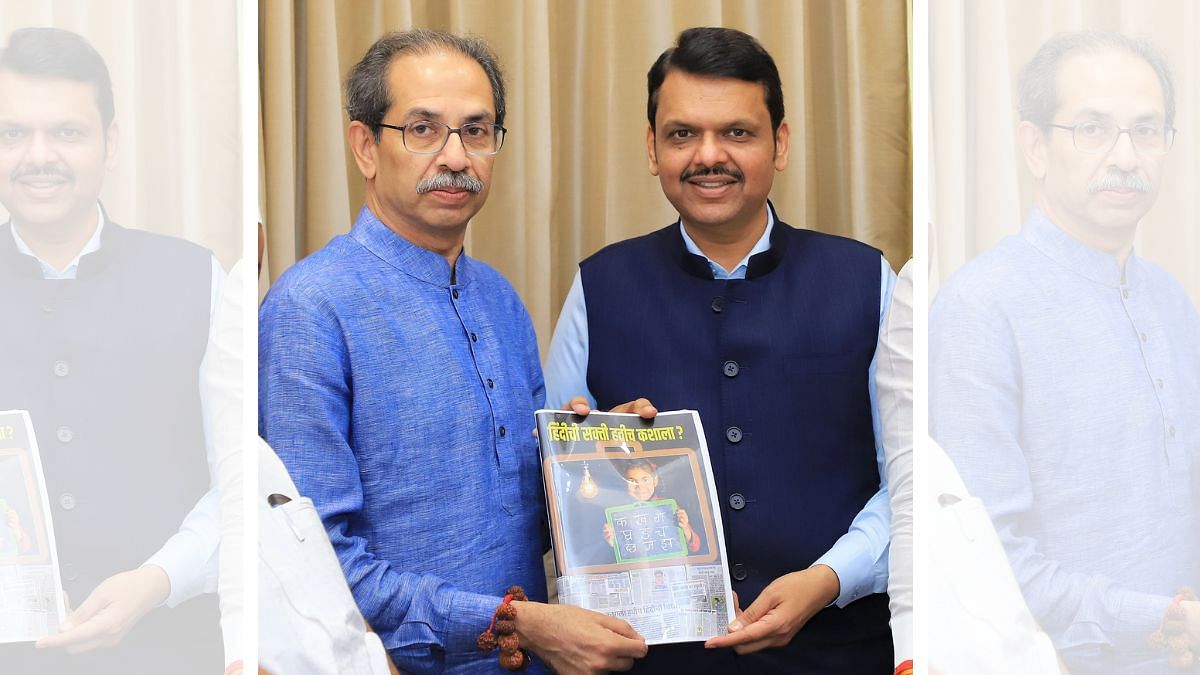

The first reason is the decline of Nitish Kumar. For nearly twenty years he has been the pivot of Bihar politics. His early years were defined by rural roads, girls’ cycle schemes, prohibition, and experiments with women’s empowerment in local bodies. He was seen as a leader who could balance social coalitions and bring governance back to the centre of politics. But fatigue has set in. His constant changes of side have damaged credibility and eroded his once firm support base. Voters no longer ask which way Nitish will tilt but who will replace him. For the first time in three decades the state faces a genuine leadership vacuum.

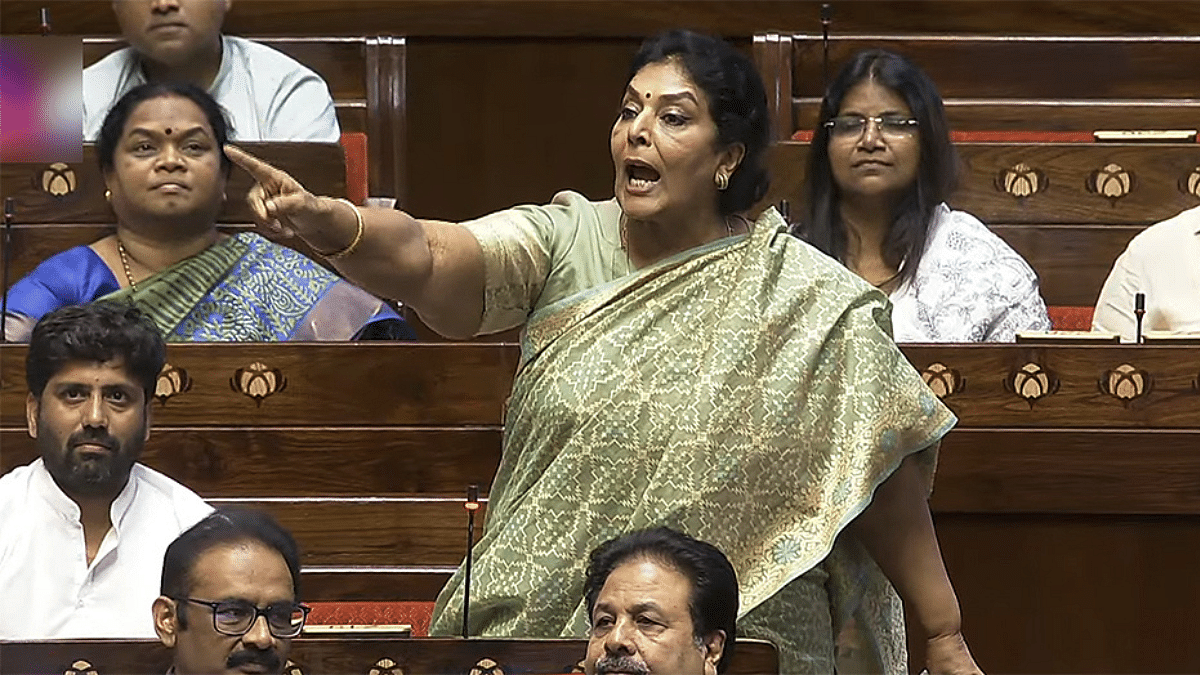

The second is the fluidity of caste equations. Bihar’s politics has long rested on predictable blocks of Yadavs, Kurmis, Koeris, Mahadalits, and upper castes. That certainty has faded. Non Yadav OBCs who were once Nitish’s anchor are restless. Mahadalits are no longer firmly tied to one party. Even upper castes, once solid behind the BJP, are weighing their options. A tectonic shift is underway in how communities view their political choices. This does not mean caste will vanish, but its arithmetic is less stable than at any point since 1990.

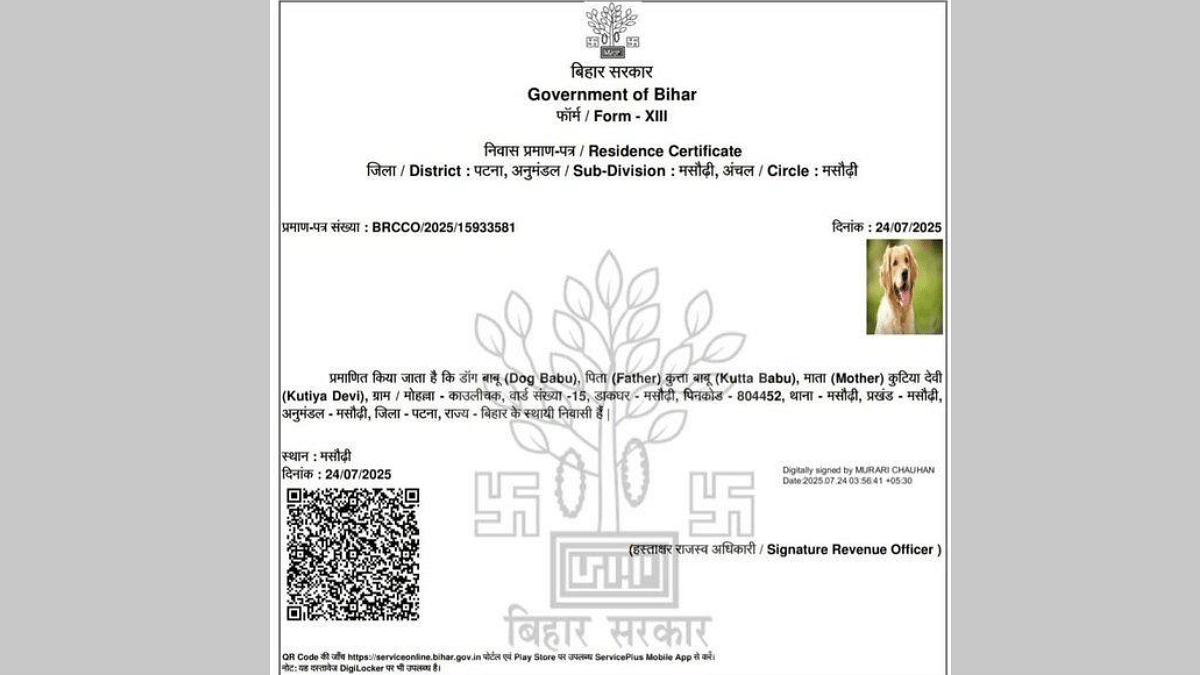

The third factor is the rise of welfare populism. Where the nineties were shaped by caste populism, today political competition revolves around direct benefits. The Bihar government provides free electricity up to 125 units per month for domestic households, benefiting millions of families. Unemployed youth between the ages of twenty and twenty five can receive monthly assistance of one thousand rupees under the Nischay Swayam Sahayata Bhatta Yojana. Women are being supported to start small ventures with initial assistance of ten thousand rupees, which can increase further depending on performance. These schemes have created a class of labharthi who see themselves less through caste identity and more as recipients of state support. Welfare cuts across caste lines, but it also deepens dependency and postpones the harder work of generating sustainable jobs and building institutions. Bihar must ask whether it can afford to remain caught in this cycle.

The fourth factor is the youth. Nearly fifty eight percent of Bihar’s people are below the age of twenty five. This is a generation that never lived under the so called jungle raj and therefore does not respond to warnings about it. Their reality is migration, unemployment, and frustration at the lack of good colleges or industries at home. They dream in the language of coaching centres, smartphones, and government job applications. For them, caste slogans and recycled rhetoric carry little meaning. They want opportunity and dignity, not reminders of past battles.

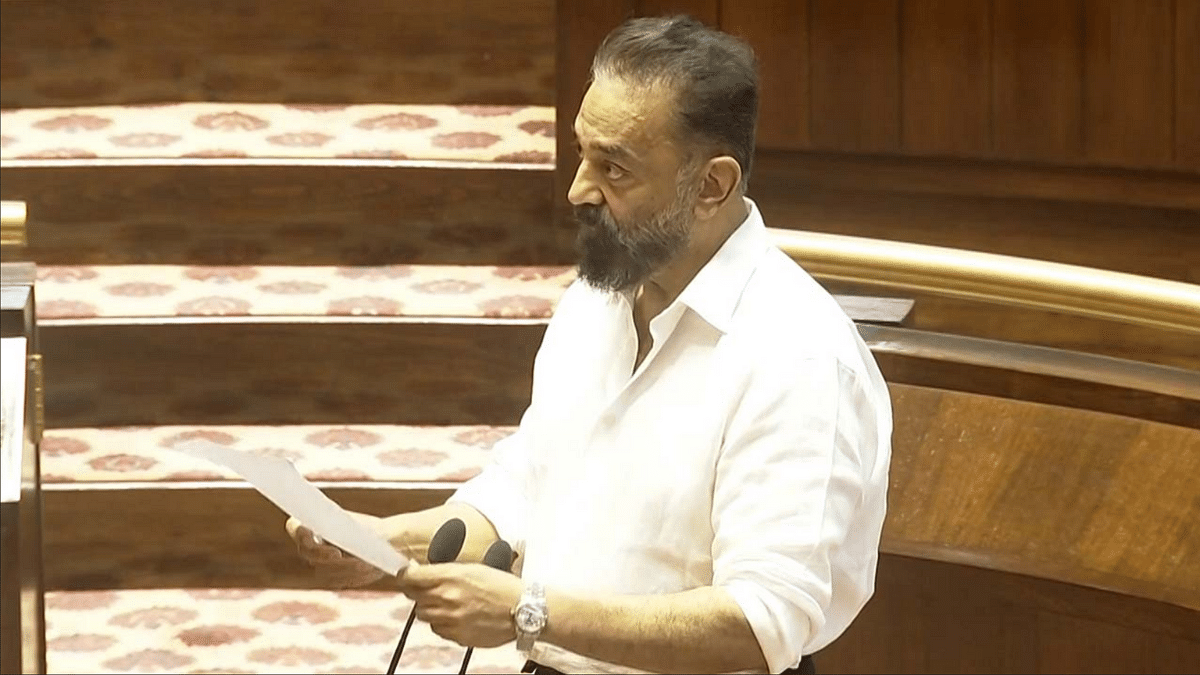

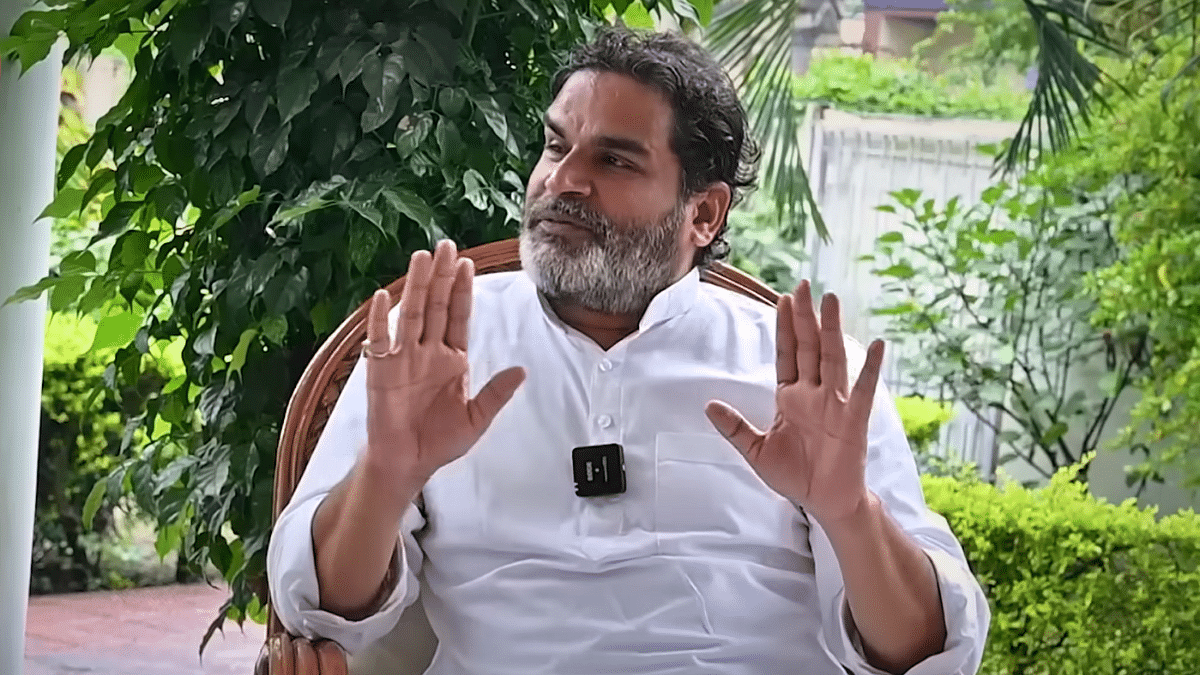

A fifth factor is the experiment of Prashant Kishor and his Jan Suraj campaign. Kishor has walked across the state, held village meetings, and drawn young volunteers into political action. He speaks the language of governance, participation, and development, not of caste or charisma. His organisation is still untested and may struggle to convert presence into votes, but it has already introduced a new idiom into Bihar’s politics. Even if Jan Suraj does not sweep the polls, it may play a role in shaping the imagination of a post Nitish Bihar.

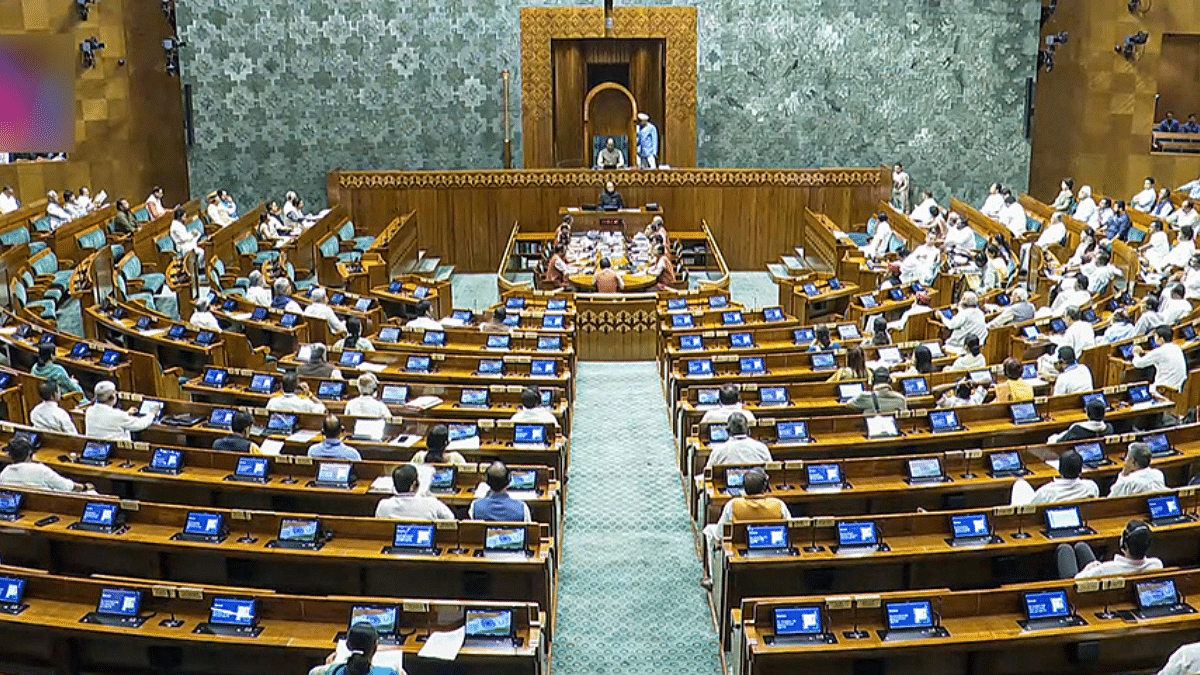

All of this matters because Bihar’s 243 member Vidhan Sabha is more than a state legislature. For three decades it has been a laboratory of coalitions and a mirror to national politics. The fall of the Congress, the rise of Mandal, the BJP’s social engineering, the experiments in governance—all found their first expression here. What Bihar decides in 2025 could alter alliances, coalition strategies, and the balance between welfare politics and governance across India.

If 1990 redefined Bihar through the assertion of caste, 2025 will test whether that vocabulary has run its course. The dusk of the Nitish Kumar era is certain. The real question is whether Bihar will continue in the cycle of caste and welfare populism, creating more labharthi, or whether it will seize this chance for a new dawn of governance, opportunity, and renewal. The land of Chanakya has cooled many would be strategists before. The test now is whether it will do so again, or finally surprise us all with transformation.

Disclaimer

Views expressed above are the author’s own.

END OF ARTICLE