- The latest Working Group on the international Plant Treaty failed to reach consensus on expanding the list of crops, addressing digital sequence information and revising the benefit-sharing system.

- Developing countries demanded clarity and equity in benefit-sharing and governance, while developed countries pushed for rapid expansion of crop access.

- Concerns related to benefit-sharing from digital sequence information, transparency, and governance took a backseat at the recent Working Group meeting.

As the Governing Body (GB) meeting of the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (ITPGRFA) approaches, key issues are gaining momentum and exposing clear divides among parties. The ITPGRFA is also known as the International Seed Treaty or Plant Treaty.

Concerns, such as payment structures, the expansion of crops covered under the treaty, and benefit-sharing from digital sequence information (DSI), resurfaced during the five-day 14th meeting of the Working Group, which concluded in Peru on July 11.

The Working Group, revived at GB-9 in Delhi in 2022, is a temporary body tasked with suggesting measures to enhance the functioning of the Multilateral System (MLS), a central mechanism under the ITPGRFA. The MLS aims to facilitate access to plant genetic resources for food and agriculture and ensure fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from their use.

Although the Working Group was expected to submit its suggestions at GB-11 in Peru, scheduled from November 24 to 29, it failed to build a consensus among the parties. The group will now forward its outcomes to the Governing Body, said Nithin Ramakrishnan, a researcher with the Third World Network (TWN), who was present at the recently concluded Working Group meeting in Peru.

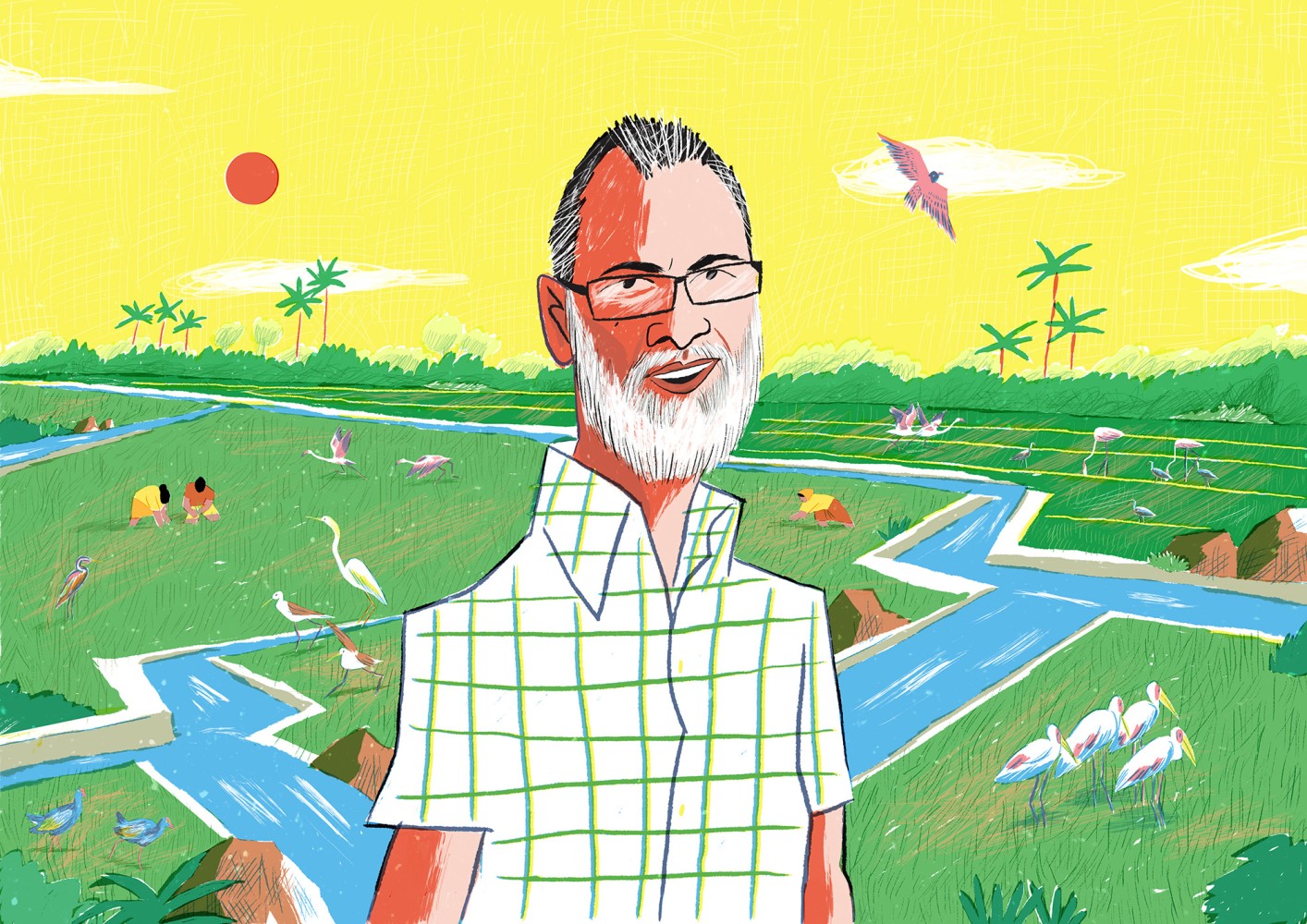

Adopted in 2001 and in force since 2004, the ITPGRFA governs access and benefit-sharing of 64 food and forage crops through the MLS. Around 18 global centres are part of this system, conserving and exchanging plant genetic resources. One such centre is the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT), based in Hyderabad. Those accessing these materials for crop improvement or product development are expected to share the benefits, explained Bhagirath Choudhary, Founder-Director of the South Asia Biotechnology Centre (SABC) and a former fellow of the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR).

Calls for enhancing the MLS have emerged within a decade of the treaty’s adoption. Two major issues, including expanding the list of crops and improving benefit-sharing, led to the establishment of the Working Group in 2013. It met nine times between 2014 and 2019, but stopped meeting due to disagreements over several issues, particularly regarding benefit sharing from DSI, which refers to data derived from genetic resources used in research. The group was revived in 2022 with a special request to give early attention to the three identified “hotspots”: digital sequence information/genetic sequence data, crop expansion, and payment structure and rates. These issues remains unresolved.

Debate about the expansion of the listed crop

The plant genetic resources for food and agriculture (PGRFA) covered by the Treaty are listed in Annex I. These 64 crops cover around 80% of the food derived from plants and are accessible under a multilateral system.

Many countries, especially the developed ones, are pushing for a full expansion of Annex I to cover all plant genetic resources, but developing countries have a different opinion about it, and also about how to proceed.

Asian developing countries, including Malaysia, Nepal, and the Philippines, opposed full expansion to all PGRFA. Their position was more cautious and favoured a phased approach, gradually including more crops over time as governance and benefit-sharing mechanisms improve. While Japan and South Korea distanced themselves from the rest of the Asian group. They supported the full expansion of the annex. India participated in recent negotiations only as co-chair of the working group, not as a country representative.

Latin American countries have shown openness to full expansion, but with a clear condition: there must be demonstrable income generation through the multilateral system. African countries have also indicated support for revising Annex I, but they propose a “positive list” approach under which crops would be added only through mutual agreement and the list would expand over time. This approach avoids automatic inclusion of all known and unknown biodiversity and ensures gradual progress aligned with stronger benefit-sharing.

There is another list called the ‘negative list’ proposed by a few developed countries. Soumik Banerjee, an independent researcher associated with Bharat Beej Swaraj Manch (BBSM), explained that countries from the Global North are proposing a model where all crops are automatically included in Annex I, but each country would have a one-time option to list exceptions and name the species they do not wish to share. These exceptions would still technically be part of Annex I, as other countries may not exclude them. Countries are expected to gradually reduce the number of species on their exception lists. BBSM is a national coalition of farmers and organisations working to integrate farmers’ rights into seed systems.

Benefit sharing under contention

Another contentious issue at the ITPGFRA meeting was benefit sharing. As per the treaty, there are two types of benefit sharing: non-monetary and monetary. In non-monetary benefit sharing, recipients of seeds have two existing obligations. First, after conducting research using the genetic material, they are required to deposit any resulting non-confidential information into the Global Information System established under Article 17 of the Treaty. This system serves as a global database. However, if the information is considered confidential by the recipient, they are not obligated to share it. The Treaty does not define “confidential,” so recipients often try to interpret it at their own discretion, said Ramakrishnan.

When it comes to monetary benefit-sharing, the current the Standard Material Transfer Agreement (SMTA), a standard contract, outlines specific conditions for this arrangement. A recipient should share monetary benefits if they develop a new seed product using materials from the MLS, they sell this seed commercially, and the seed is not made available for further research and breeding. Only when all three conditions are met does the recipient need to pay a share of the profits or revenue to the Benefit-Sharing Fund, experts highlight.

Developing countries and farmers’ groups have repeatedly raised concerns over these loopholes. Over the past two decades, approximately 6.6 million varieties of seeds & planting materials have been shared with nearly 25,000 users. However, only six recipients have contributed to the Benefit-Sharing Fund, totalling $824,680, which is approximately 2.2% of the Fund’s total.

“These invaluable seeds, along with their genomic sequences, have been carefully developed over generations by farmers and continue to be revered as sacred heritage. Yet they are being shared for private profit, without any consent or participation of the very communities who created them,” said Soumik Banerjee.

Many stakeholders, especially from developing countries, have demanded revisions to the rate structure and stronger guarantees of payment before considering expansion of the Annex.

The African Group was demanding that 0.1% of global seed sector turnover be contributed to the Benefit-Sharing Fund as an annual subscription. On the other hand, Asian developing countries have not made strong statements on payment rates in recent meetings. However, in a written submission to the 14th meeting, they called for expanding the scope of benefit-sharing. Currently, the SMTA only applies to seed sales. However, seeds accessed under the Treaty can also be used for other purposes without sharing any benefits from related products. Asian countries have raised this issue in their written submission; they did not get an opportunity to discuss it during the 14th meeting, said Nithin Ramakrishnan, adding that it happened due to the way the agenda was structured, and it came at the end.

Several countries have made it clear that Annex expansion must be linked to a stronger, more equitable benefit-sharing system. Their position is that the MLS must first prove it can ensure fairness and accountability in sharing the benefits from the 64 crops already included in Annex I.

Digital sequencing and transparency take a backseat

Benefit sharing from Digital Sequence Information (DSI) was another major issue. This has created trouble for the whole treaty for at least a decade. The present Working Group had come to a standstill in 2019 due to friction among parties, and DSI was a prominent reason for this, according to experts.

Several parties from the developing world have been raising the issue of DSI/GSD. However, the issue didn’t witness any progress in Peru. The Co-Chairs’ proposal and the Global North do not want DSI generated from the shared genetic materials to be addressed in the SMTA. The developing countries reiterated their position from the 13th meeting that DSI should be addressed within the SMTA.

Whatever text developing countries had placed in the SMTA during the 13th meeting remained there and was not discussed. This will now be taken to the Governing Body, said Nithin Ramakrishnan.

Regarding concerns about governance, Ramakrishnan said there are practically no solutions suggested for improving accountability and transparency. To the contrary, three additional confidentiality protection clauses have been added to the SMTA. Asian developing countries have opposed these inclusions as they are internally inconsistent with other parts of the SMTA and Article 10 of the Treaty, Ramakrishnan informed.

Concerns and absence of India

Farmer associations in India have expressed concerns over governance issues in the treaty negotiations. Rashtriya Kisan Mahasangh (RKM) wrote to the Prime Minister on July 4, raising objections to the package of measures proposed by the Co-Chairs. K. V. Viju, national coordinator of RKM, questioned the lack of accountability and transparency. He said, “The proposed package is forcing countries to contribute more genetic resources to a failed benefit sharing system. Even worse, if adopted, the package of measures will obligate Parties to share their plant genetic resources to a system that inherently lacks accountability and transparency..” He added that India and its farmers stand to gain nothing from the proposal and requested a proper analysis.

RKM and BBSM have also raised another concern. BBSM wrote a seperate letter on July 2, and said that India’s role as Co-Chair of the Working Group could be seen as its official position. The letter said, “We are worried that this situation could co-opt India into the proposals prepared by the Co-Chairs, without a discussion on such proposals within India and with farmers groups.”

Nithin Ramakrishnan confirmed that India was present only in its capacity as Co-Chair and did not participate as a negotiator.

When asked about this, Narasimha Reddy, a policy expert on seeds and agriculture, said that India is not giving due importance to the opinions of farmer organisations. First, it has not yet understood the implications of the MLS treaty on Indian agriculture and its farmers. “I do not think there has been any formal assessment by the Government of India. They seem unaware of the serious consequences that could follow once the MLS comes into effect,” he said.

V. Viju said they are waiting for the final outcome of the Working Group meeting and will respond after that.

Read more: The international treaty on plant genetics moves a step ahead with farmers’ rights and DSI

Banner image: A woman winnows food grains in India. Adopted in 2001 and in force since 2004, the Plant Treaty governs access and benefit-sharing of 64 food and forage crops. Image by Subrohit via Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY SA 4.0).