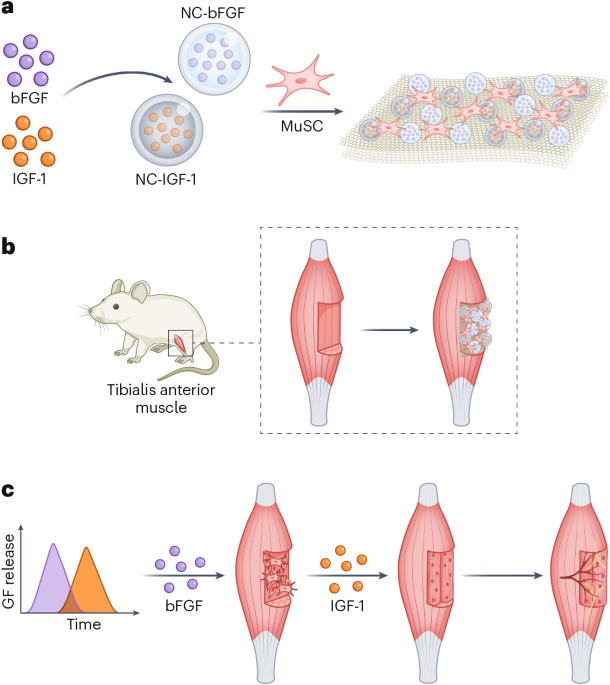

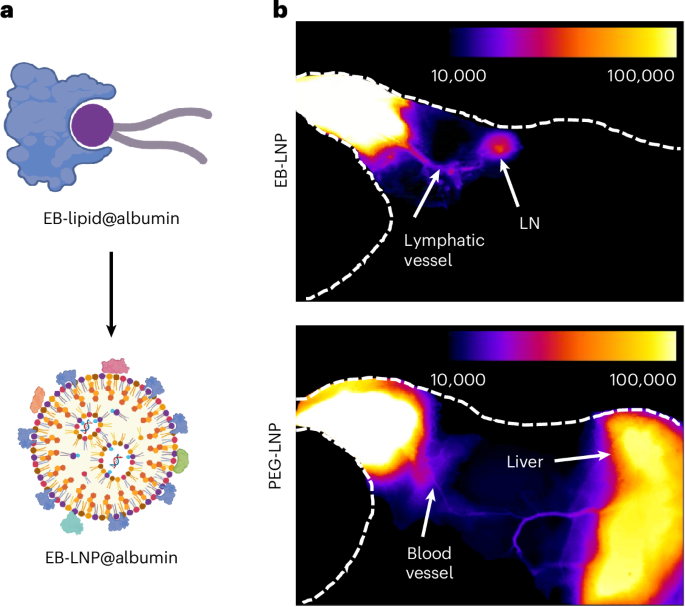

- Street vendors in Delhi broadcasted weather warnings by putting up heat alert boards near their carts.

- The meteorological department provided daily weather updates, including audio messages, which were circulated via WhatsApp to a larger circle of workers.

- Improving awareness about extreme heat is the first step to building resilience, experts said.

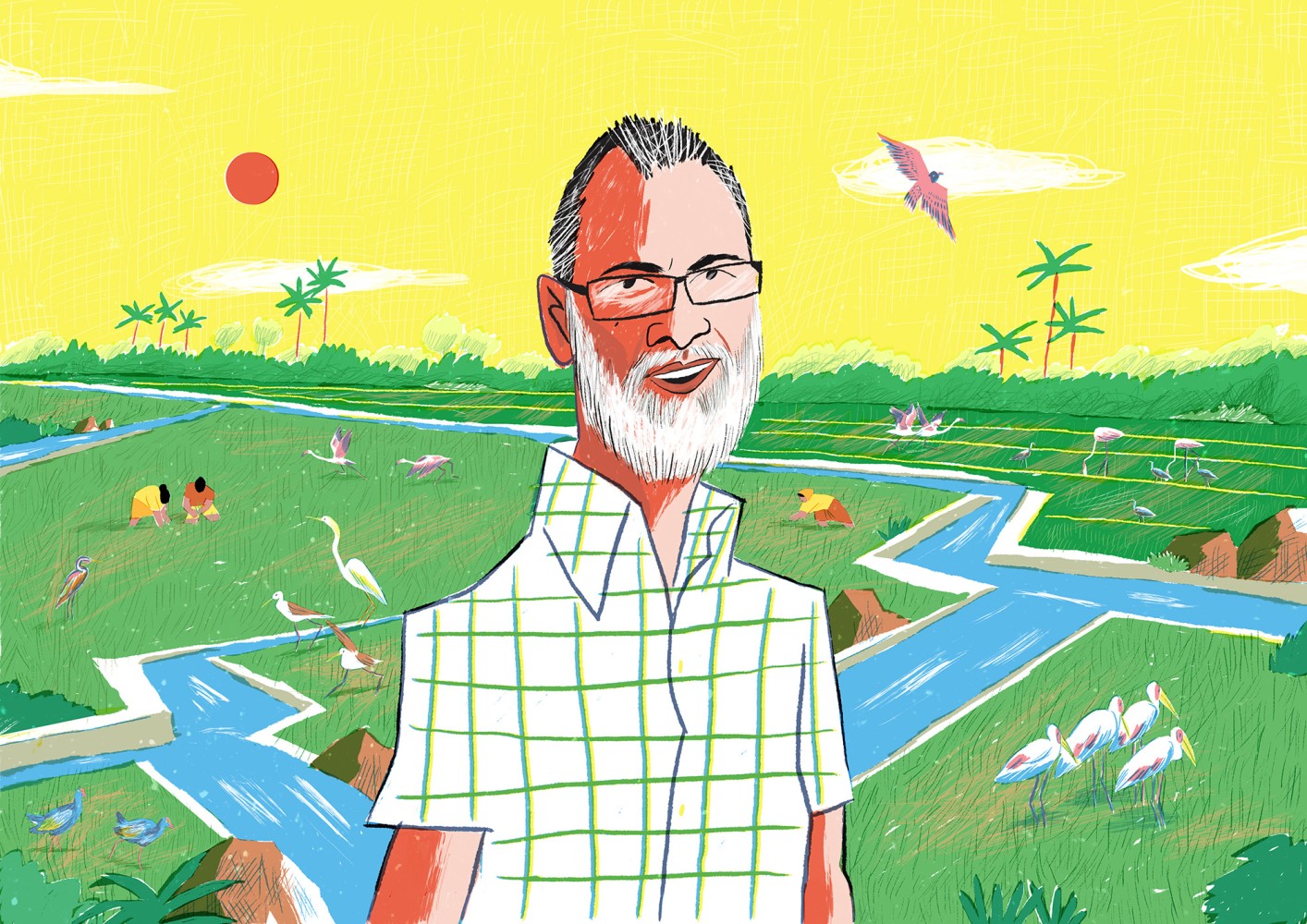

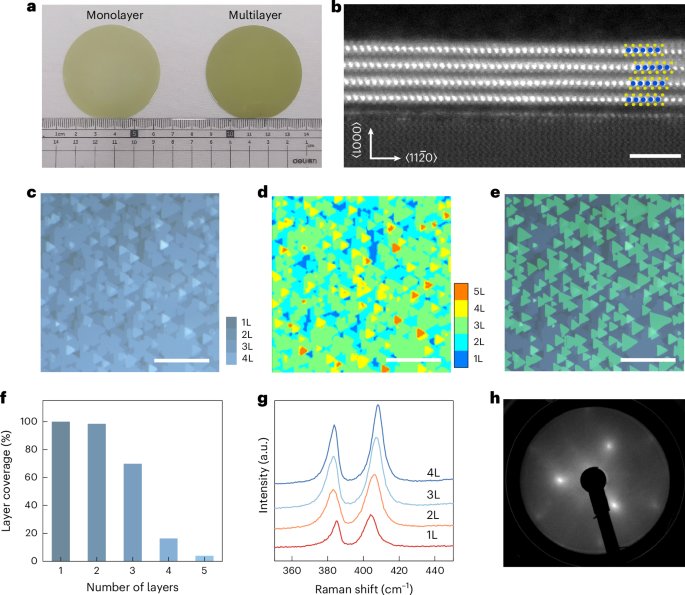

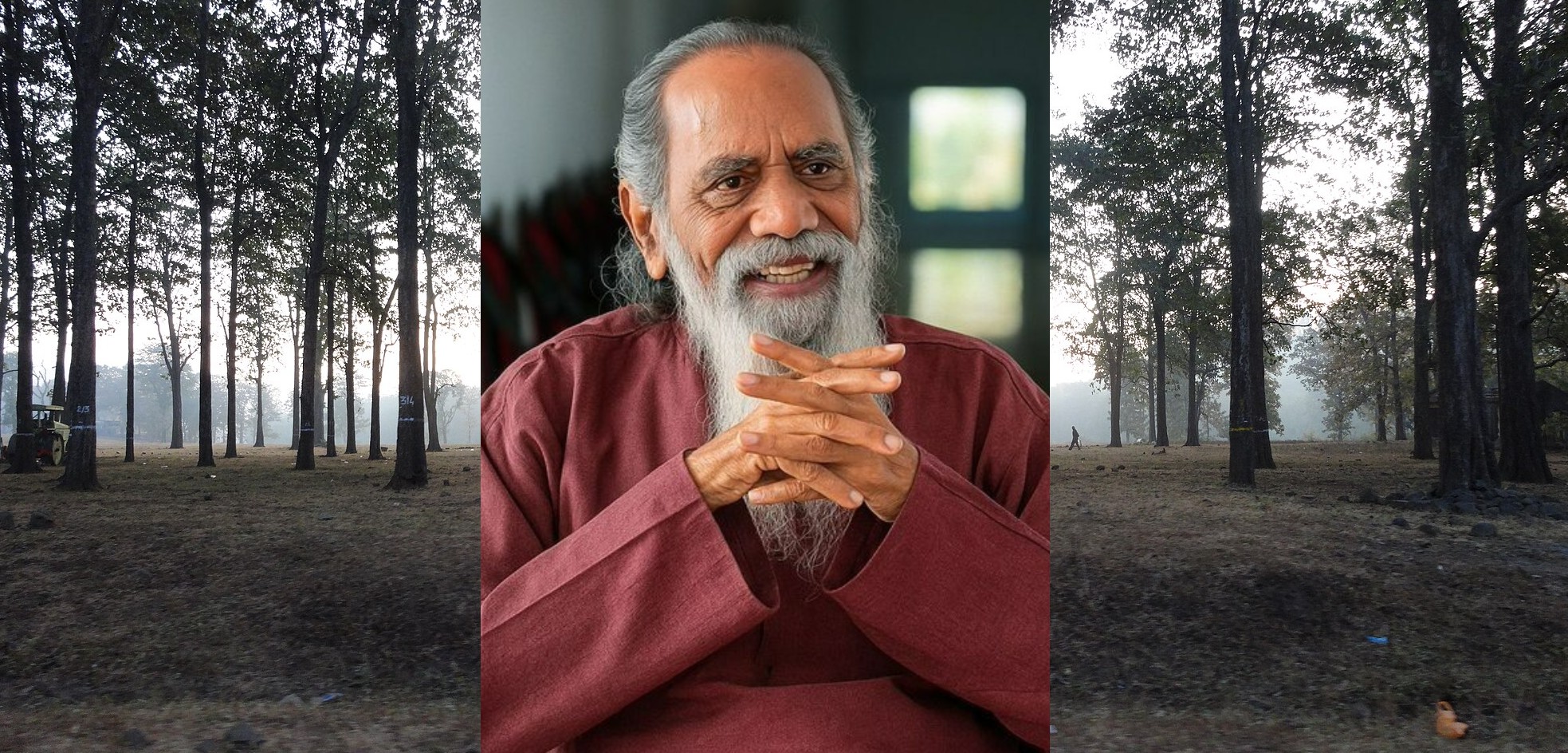

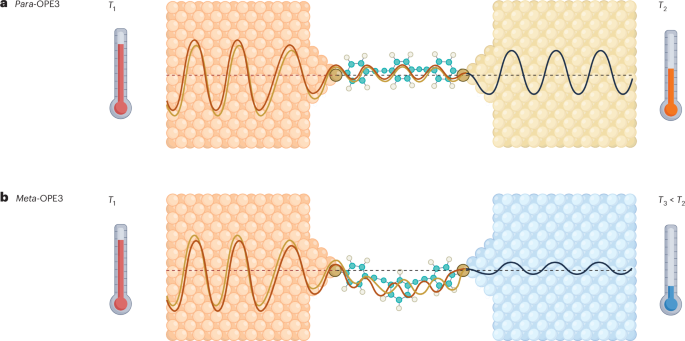

On a hot June afternoon, Aslam Khan, a street vendor in Delhi, directed curious tourists and fellow informal workers towards a yellow-coloured board installed next to his garment cart. The board read ‘Asahaj Garmi’ (uncomfortable heat) in Hindi with a large ‘hot face’ emoji plastered on it. Alongside the emoji were to-dos, health precautions, and a brief write-up of the weather.

“Five years ago, I had not even heard the term climate change. And now, I am raising awareness of the day’s weather among other workers,” said Khan while sitting at his cart in the Meena Bazaar market in front of the historic Jama Masjid. “Tourists passing by the cart often click a photo of the board. Lots of workers read it. Those who cannot read, ask us for the details,” he added.

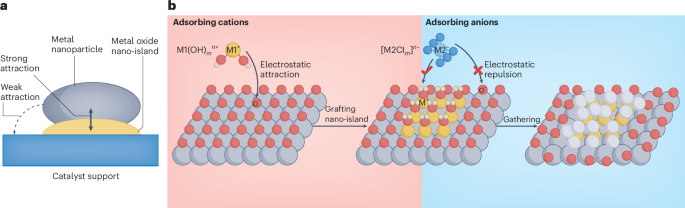

These colour-coded boards were launched on June 12 by the India Meteorological Department (IMD) as part of a collaboration with informal worker organisations and the non-profit Greenpeace, to improve weather warning systems. Workers such as Khan call themselves “climate messengers”, who bear the essential task of amplifying information that could help passers-by cope with extreme heat.

Aravind Unni, a Delhi-based urban practitioner and researcher, said informal workers are in an “information black hole” when it comes to the impacts of heat stress. “Information sharing in a more publicly accessible manner can be very empowering and can support workers to act better. It’s the very first step of building resilience for such groups,“ he said.

Heat alert boards

Mohammad Nasim, a 40-year-old migrant street vendor in Delhi, recalled how in June, when temperatures were recorded to be 43.9°C, a fellow vendor from his market felt dizzy and had to be hospitalised — a likely case of severe heat illness.

“These incidents are common. We work on the street for 14 hours a day. It is hot, humid and the fume from vehicles makes us feel hotter,” Nasim said, as he helped a customer try on a pair of sneakers in his cart. His customer, 24-year-old Saurabh Kumar, works part-time with a food delivery app. The board caught his attention as Nasim explained the idea behind it.

“I have never seen anything like this before,” Kumar told Mongabay India, adding, “Reading this, I was instantly reminded that I have not had water for two hours now as I was fulfilling delivery orders.”

These heat alert boards — which carry simple instructions in Hindi, like wearing full sleeved clothing, not eating stale food, and drinking water every 20 minutes — are more eye-catching and specific compared to regular advisories, workers said. To reach a wider audience, including those who may be illiterate, the boards are colour-coded, and the weather warnings expressed as emojis.

The boards were redesigned to improve recall value after rounds of feedback from street vendors, said Selomi Garnaik, a climate campaigner at Greenpeace. Initial hand lettered notices on white background made way for more attractive, colourful boards.

This year, 25 colour-coded boards were provided by Greenpeace and put up in 10 locations in the city which are frequented by labourers and other informal workers. Worker groups involved in the campaign want to take the initiative forward by “replicating them (the boards) using low-cost materials,” said Garnaik.

Making weather warnings accessible

This collaboration with the IMD took root in April, when groups of street vendors, waste pickers, gig workers and others first approached the IMD with the quandary of how to make weather related warnings more accessible to outdoor workers. Most informal, outdoor workers and supervisors don’t perceive heat to be a threat to wellbeing, even though it impacts both health and productivity.

Following the meeting, a WhatsApp group named ‘Daily Bulletin -IMD/Citizens’ was set up. The IMD shares weather alerts and bulletins in English and Hindi, which are forwarded by worker representatives to their local WhatsApp groups on a daily basis. This then guides workers to choose the correct colour display for the boards installed near their carts.

For workers with smartphones, WhatsApp is an agreeable platform because it is their primary mode of communication and is easy to use. But what truly made the warning system more effective than conventional SMS alerts, workers said, was the frequency with which the warnings were issued and the option to listen to them via WhatsApp’s voice note facility.

“The ultimate objective is that weather warnings by IMD should directly reach those who are being affected,” said Akhil Srivastava, a scientist with the IMD. “This is currently a pilot project and focuses largely on heat alerts. We are now planning to see how it can be expanded to other weather phenomena like thunderstorms, cold waves, fog and heavy rainfall, all of which impacts this group.”

Sustaining worker involvement

In addition to the heat boards, workers also devised other methods to beat the heat. This includes using cloth canopies above vending carts instead of heat-trapping polythene ones and setting up hydration points in the large market areas in Delhi.

“It is important to be aware first and then move to finding solutions. The next step will include encouraging vendors to end plastic usage and promote renewable energy sources,” said Sandeep Verma, convener of the Indian Hawkers Alliance.

While the IMD’s engagement with workers is “appreciable,” Unni said the focus should now shift to institutionalising the process. “Information and awareness need to be followed up with welfare support measures and compensation. Workers also need to be supported and made a part of processes like disaster management and heat action plans.”

Back in Meena Bazaar, Khan echoed the same sentiments, reiterating that while awareness helps, vendors like him still have to work in the absence of basic facilities like clean drinking water, shaded roofs and washroom facilities. “For this one canister (containing cold drinking water) alone, I spend ₹20 daily which is a monthly expense of ₹600. While heat halves our incomes, it doubles our expenses,” he said, taking a gulp of cold water.

Read more: Surviving a heat stroke, one year later

Banner image: Aslam Khan next to the heat alert board, showing different colour coded options. Image by Anuja.