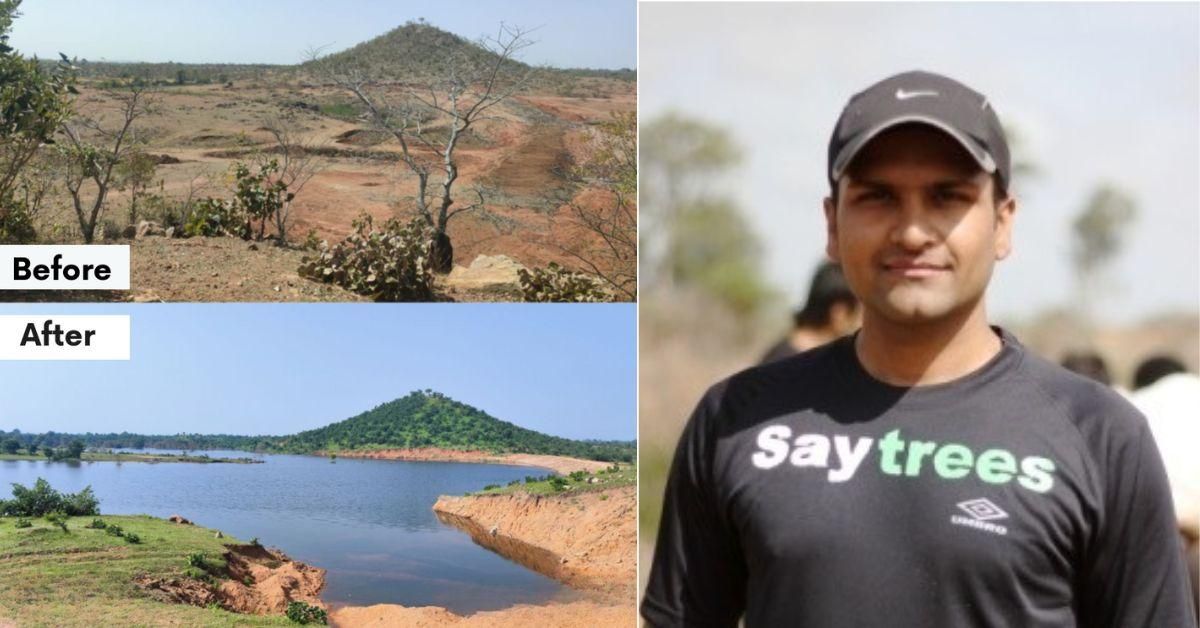

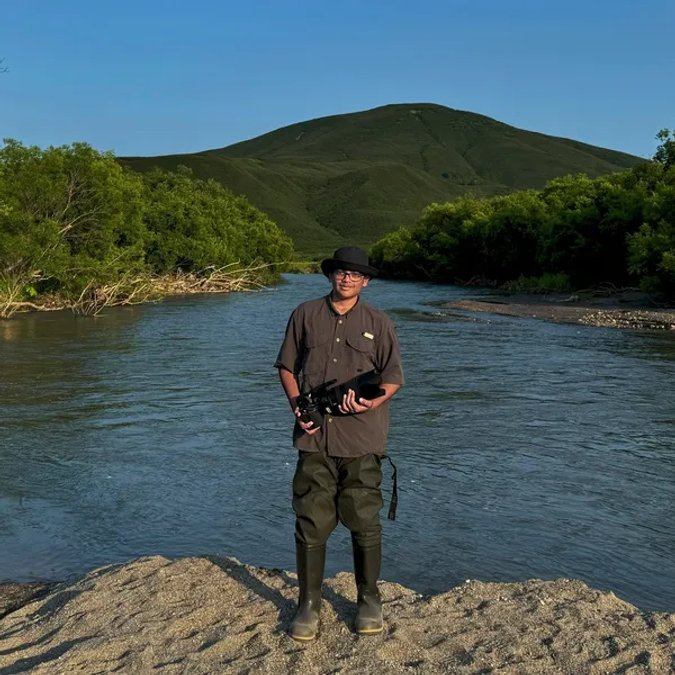

On a scorching summer afternoon in 2022, wildlife photographer Sharvan Patel stood quietly near a dried-up waterhole at the edge of Rajasthan’s Tal Chappar Sanctuary.

The land stretched endlessly before him — brown, cracked, and thirsty.

A herd of blackbucks hovered hesitantly around the shallow pit, their hooves sinking into dust. A mongoose darted in, only to scurry away when its nose touched the muddy trickle left at the bottom.

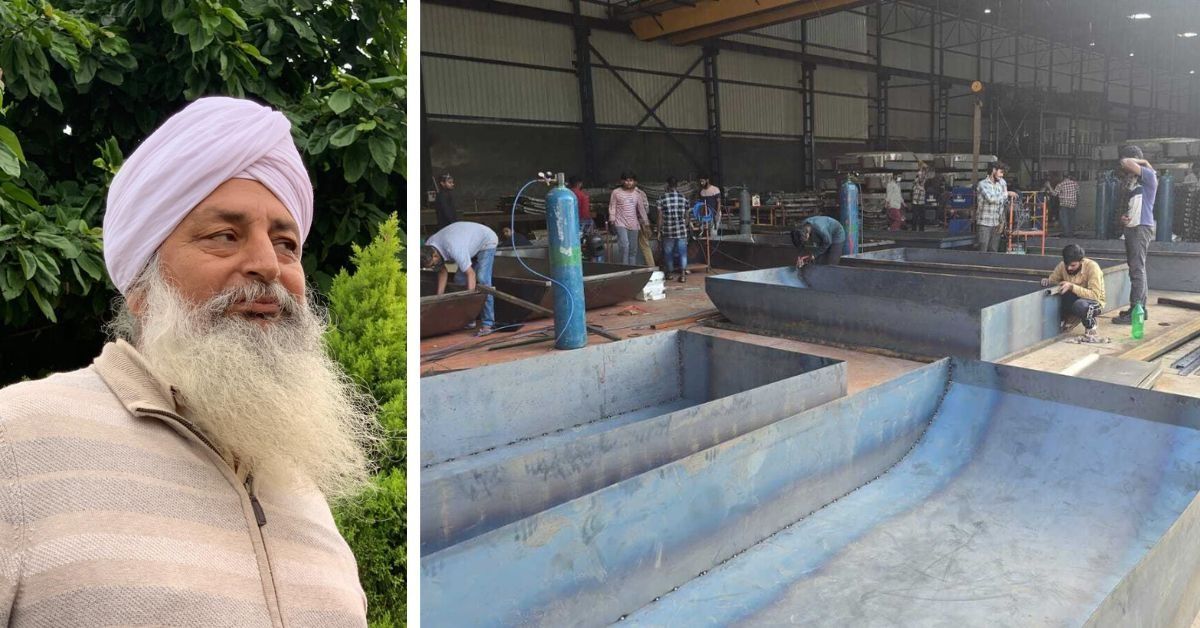

Sharvan raised his camera, but the weight of the moment felt heavier. “That day, as I watched life wilt for the lack of water, I made a promise to myself that I would bring back water for wildlife in the desert,” he recalls.

What began with that promise would later turn into a movement of building ponds across Rajasthan’s drylands, transforming empty stretches into oases where animals could drink, rest, and thrive.

An accidental discovery

Sharvan was not always a conservationist. He began as a wildlife photographer, chasing frames of raptors and deer across Rajasthan’s semi-arid stretches. One such photography trip — to Tal Chappar — changed everything.

A friend, a bank manager and part-time wildlife enthusiast, had taken Sharvan along on an audit duty near the sanctuary. While his friend was busy scanning the skies for raptors, Sharvan’s eye caught something on the ground — a freshly built pond, locally called a khaili.

/filters:format(webp)/english-betterindia/media/media_files/2025/09/12/shravan-patel-5-2025-09-12-18-50-55.jpg)

Curious, he crouched down and began measuring the pond’s length and width with his bare hands. Soon, forest guards arrived. Sharvan bombarded them with questions, and they explained that the pond was an experiment, designed to provide water to wildlife during the driest months.

At first, animals kept away. But within weeks, the pond became a hub: hares paused to drink, mongooses darted in, peafowls strutted around its edge, and even cautious blackbucks began visiting.

Sharvan was fascinated. He returned home to Melwa village with the images etched in his mind. For him, this pocket of water told a deeper story than any photograph could.

The first pond that changed everything

In the summer that followed, Sharvan decided to build his own pond with a small group of friends. It was modest in size, just half a foot deep, and modelled after the traditional village ponds he had grown up seeing. They used local soil, added cement to reduce seepage, and built an embankment to hold the rainwater.

At first, nothing happened. Days passed with barely any visits. The pond stood still, almost forgotten. Then one night, Sharvan’s camera traps captured a miracle: blackbucks bending gracefully to drink, flocks of birds circling above, and nocturnal mongooses padding in under the cover of darkness.

/filters:format(webp)/english-betterindia/media/media_files/2025/09/12/shravan-patel-6-2025-09-12-18-51-15.jpg)

Excited, Sharvan filmed the activity and shared it online. The video went viral, sparking an outpouring of messages. Villagers, influencers, and nature enthusiasts urged him to replicate the effort in their areas. “Come here,” they pleaded. “Animals are dying of thirst.”

What had begun as a photographer’s experiment had turned into a movement.

When the desert spoke of thirst

Sharvan’s work soon took him beyond Tal Chappar. In the villages of the desert, he witnessed heartbreaking scenes. Birds lay stiff near dried pits, mongooses collapsed from heat, and herds of deer circled empty tanks in search of water.

One of his most painful captures showed a deer standing at the edge of a shallow pit, unable to drink because the water had sunk too deep.

He realised that two forces were at play here. The first was the sheer scarcity of natural water in Rajasthan’s desert stretches. The second was the contamination of whatever little water remained, polluted by chemicals from agriculture and unfit for animals to drink.

It was here that Sharvan turned to reviving an old tradition. Traditionally, khailis were shallow village ponds built with earth and natural clay to hold monsoon water. Sharvan adapted this practice with small innovations — cement lining to minimise seepage and ensure the water stayed cool longer, then layering it with soil to give a natural base.

The cost was modest, about Rs 30,000 to Rs 40,000 for material and labour, yet the impact was immense. In places where no water had existed for miles, these ponds became lifelines for animals.

The cost of keeping ponds alive

Building ponds was only half the battle. Keeping them filled through Rajasthan’s scorching summers proved even harder.

/filters:format(webp)/english-betterindia/media/media_files/2025/09/12/shravan-patel-3-2025-09-12-18-51-45.jpg)

From March to July, temperatures soared and natural water vanished. Tankers became the only lifeline. In April, Sharvan recalls, a single tanker cost around Rs 1,000. By June, the price had doubled to Rs 2,000, with the nearest government reservoir lying 20–25 kilometres away. The logistics were punishing and expensive, but without these tankers, the ponds would dry up and the animals would once again be left with nothing.

Smallest contributions, big changes

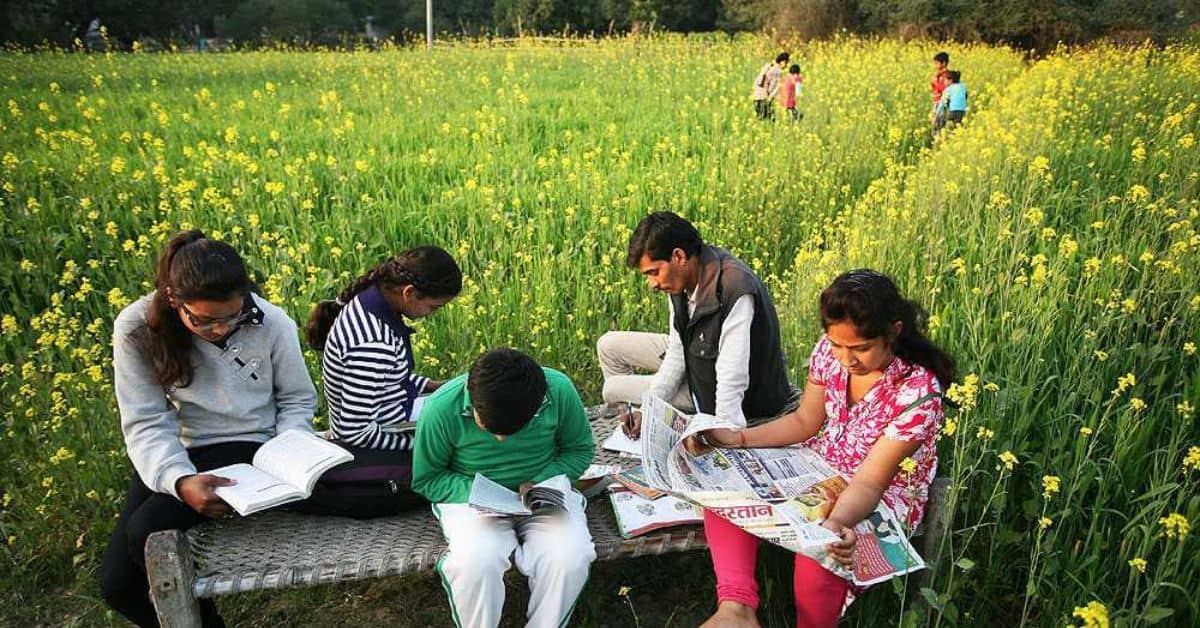

To keep the ponds alive, Sharvan and his team launched a simple but powerful campaign: asking people to donate just Re 1 a day. The idea, suggested by his friend Yashovardhan Sharma, was that when people are financially invested, they remain emotionally invested too.

They created a WhatsApp group called ‘One Rupee Per Day for Wildlife Conservation’. Soon, support began to trickle in, and the idea took shape as a larger movement. Nearly 1,000 members joined, each contributing Rs 365 a year.

“These small but consistent contributions funded habitat restoration, protection of endangered species, and even improvements in local farming practices,” explains Yashovardhan, who serves as secretary in Rajasthan’s environment cell of INTACH (Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage). “This has helped us raise funds for plantation efforts, filling up watering holes, and the removal of invasive species.”

Social media also played a key role. Sharvan’s Instagram page, ‘Thar Desert Photography’, spread awareness and drew more people to the cause.

/filters:format(webp)/english-betterindia/media/media_files/2025/09/12/shravan-patel-2-2025-09-12-18-52-04.jpg)

“True conservation is not about large sums of money, but about small, consistent efforts,” Yashovardhan says. “When communities unite, even a single rupee a day can revive history and heal nature.”

But along with support came hurdles too. Shepherds sometimes drove their goats into the ponds, muddying the water and driving away wild deer. Yet Sharvan persisted. “When a peacock dances near the pond or a vulture circles down for a drink,” he says, “every rupee feels worth it.”

To date, Sharvan has been directly involved in constructing over 30 ponds. His videos and guidance have also inspired communities across Bikaner, Jodhpur, and Jaisalmer to build more than 100 ponds of their own.

When the desert turned into an oasis

The results soon spoke for themselves. Camera traps showed mongooses arriving in flocks, peacocks unfurling their feathers, and migratory birds returning to rest. Sharvan even recorded vultures perched solemnly around the ponds, turning the desert into what looked like an oasis.

The most striking change was among blackbucks, whose numbers swelled in areas near the ponds. Instead of wandering into villages where they risked conflict, they now stayed closer to water-rich zones.

/filters:format(webp)/english-betterindia/media/media_files/2025/09/12/shravan-patel-7-2025-09-12-18-52-23.jpg)

“Wildlife appears where there is water,” Sharvan explains simply. “It is the heart of every habitat.”

His images capturing this revival carried the message further. Photographs and short films he created began circulating widely, and soon Rajasthan Tourism showcased his work, presenting Tal Chappar as a destination where photography and conservation came together.

The next chapter for Rajasthan’s wild

For Sharvan, the mission does not end with ponds. He dreams of every village nurturing a mini forest within its oran, the traditional sacred community land. “If villagers plant native trees and protect small water bodies, species like chinkaras, foxes, and blackbucks will thrive naturally,” he says.

He believes such efforts could also support eco-tourism. Homestays, local food, and wildlife safaris could bring livelihoods to villages like Melwa, his own home. “Children shouldn’t have to travel miles to see wildlife. They should grow up with it around them.”

When asked if he considers himself a conservationist, Sharvan pauses. “I never thought I’d do this,” he admits. “It began with one pond, then another. Now it feels like a purposeful responsibility.”

For him, the mission is clear: to keep water flowing where animals need it most. And so, in the heart of Rajasthan’s drylands, Sharvan is known as the man who brought ponds to a thirsty land, ensuring that in the middle of the desert, life still has a chance to drink and dance.

Edited by Khushi Arora; All images courtesy: Sharvan Patel, Thar Desert Photography.