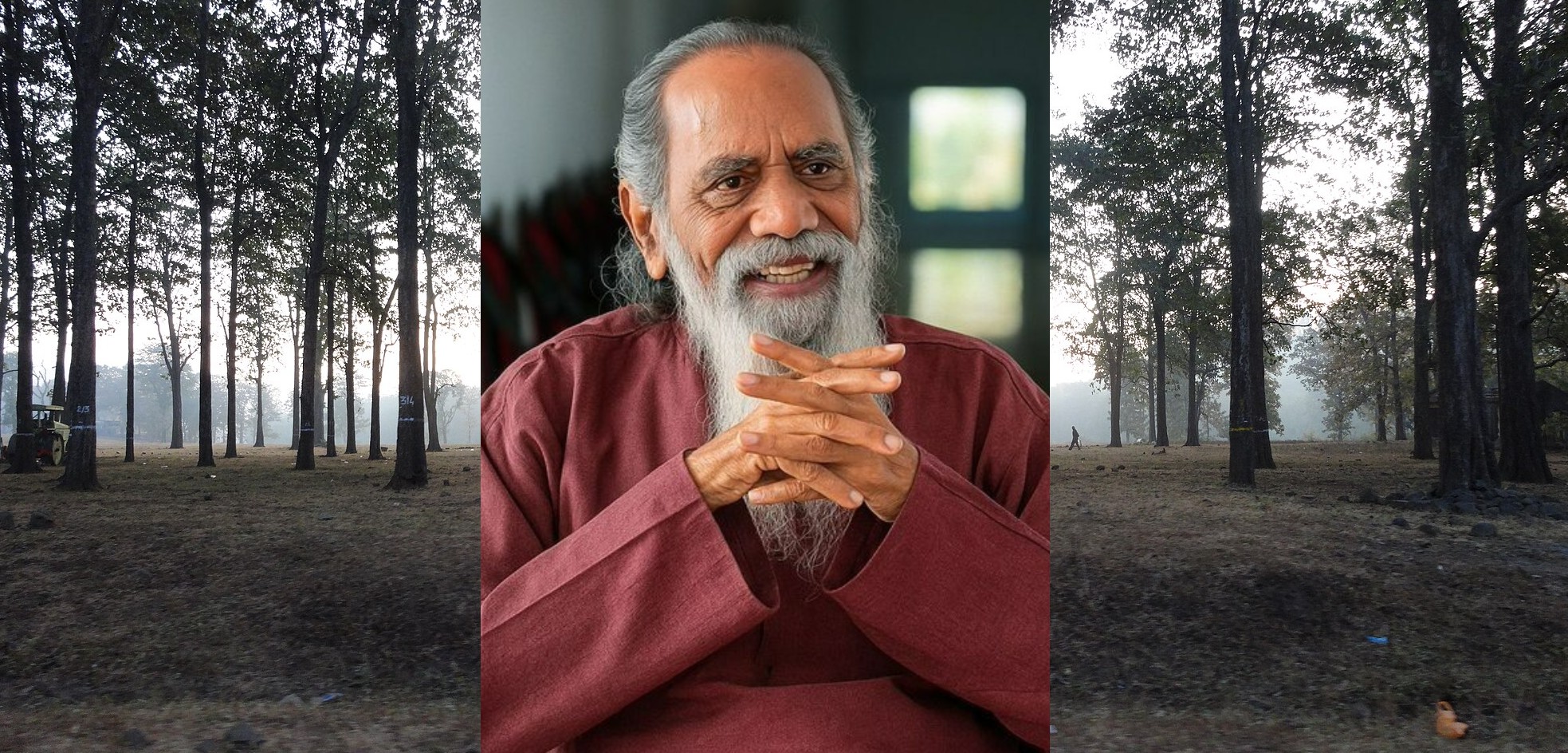

India is stepping up efforts to ensure a steady supply of rare earth elements and magnets—materials that are key to its clean energy push, greening transport, and defence sector—in light of China’s recent decision to tighten exports of these critical resources.

China dominates the rare earth market, producing around 60% of the global supply and processing nearly 90%. Reacting to the export curbs, Union Commerce Minister Piyush Goyal, during an interaction with the media, called the decision a “wake-up call for the world”. Automakers worldwide are increasingly concerned, with early signs of production adjustments already visible in some markets.

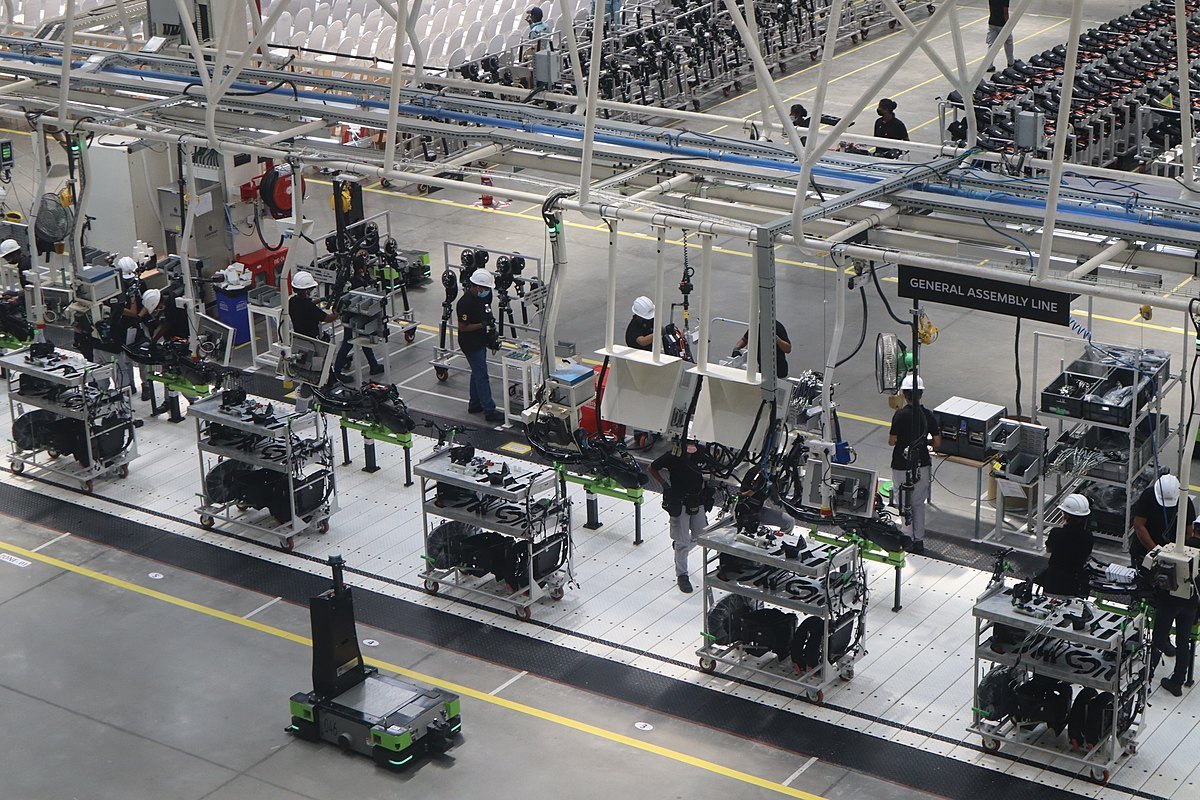

“Electric vehicles will be the worst hit, with production delays of two to six months and price hikes of 5-8%. For a ₹1.6 lakh (₹160,000) electric scooter, that means an increase of ₹8,000-13,000,” says Ravi Bhatia, President and Director of automotive market intelligence firm JATO Dynamics India. Even conventional vehicles rely on rare earth magnets for components such as power steering systems and wipers.

The disruption in the supply chain of rare earths could slow down India’s electric vehicle plans and hurt the economy. To deal with this, India is looking for new supply partners in other countries.

According to media reports, the Indian government is likely to ask the public sector company IREL (India) Limited to stop sending rare earths to Japan to conserve them for domestic use. At the same time, talks with China are ongoing to ease the situation.

But true independence can’t come through diplomacy alone, Bhatia notes. “It needs strong policy support, risk capital, and time. Even if we establish some domestic production in 6-7 years, it will be a significant step forward. The key is to look beyond China—and start now.”

The demand for rare earths extends far beyond the automotive industry. For India to meet its 2070 net-zero target, a reliable supply of rare earth elements, alongside lithium, cobalt, and nickel, is crucial. Neodymium and dysprosium are especially important for wind turbines, with each megawatt of wind capacity requiring about 200 kg of rare earth materials.

Despite having the world’s fifth-largest rare earth reserves—estimated at 6.9 million metric tonnes—India remains a major importer. In 2023, it ranked 17th globally, importing rare earth compounds worth $13.1 million.

So why hasn’t domestic production scaled up? “Setting up a rare earth mine requires a massive investment and a gestation period of nearly a decade,” says Bhatia.

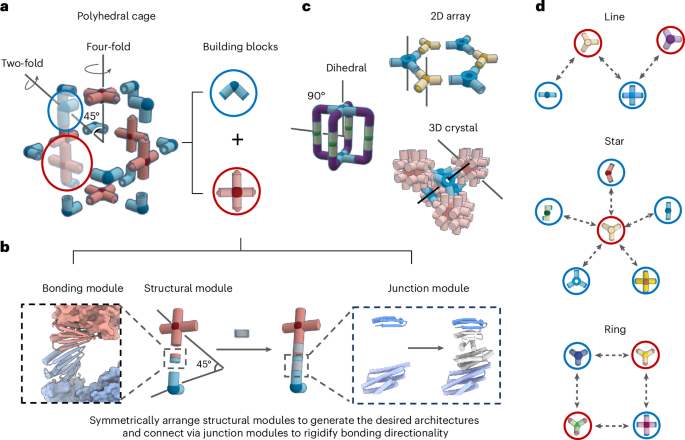

Banner image: Electric scooter manufacturing unit. Image by Gnoeee via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).