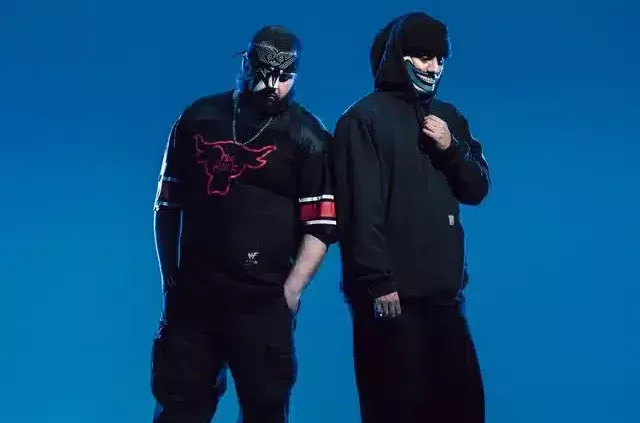

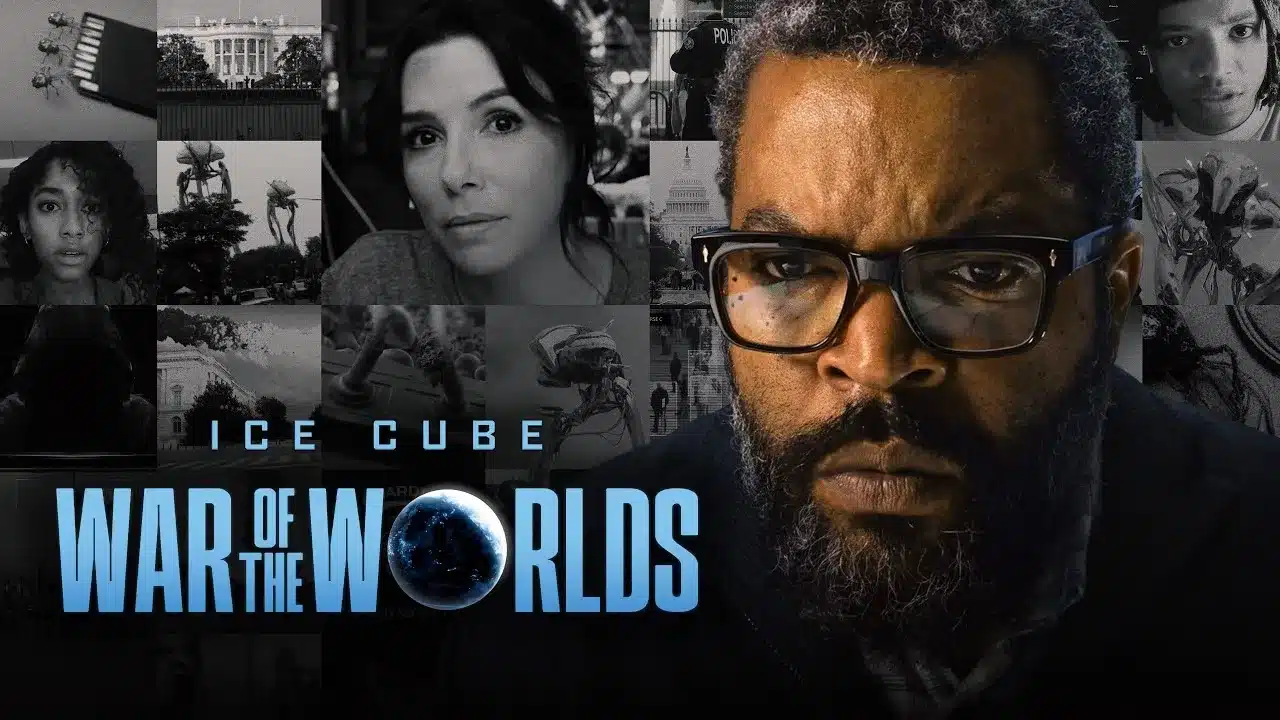

Him, the Jordan Peele-produced splatter movie directed by Justin Tipping, attempts to reinvent the sports movie genre by combining psychological horror with America’s most iconic pastime – tackle football.

Rather than presenting a biting commentary on the cruelty and exploitation that characterize the sport, the film trips over its own implausibility, tonal inconsistency, and narrative excess.

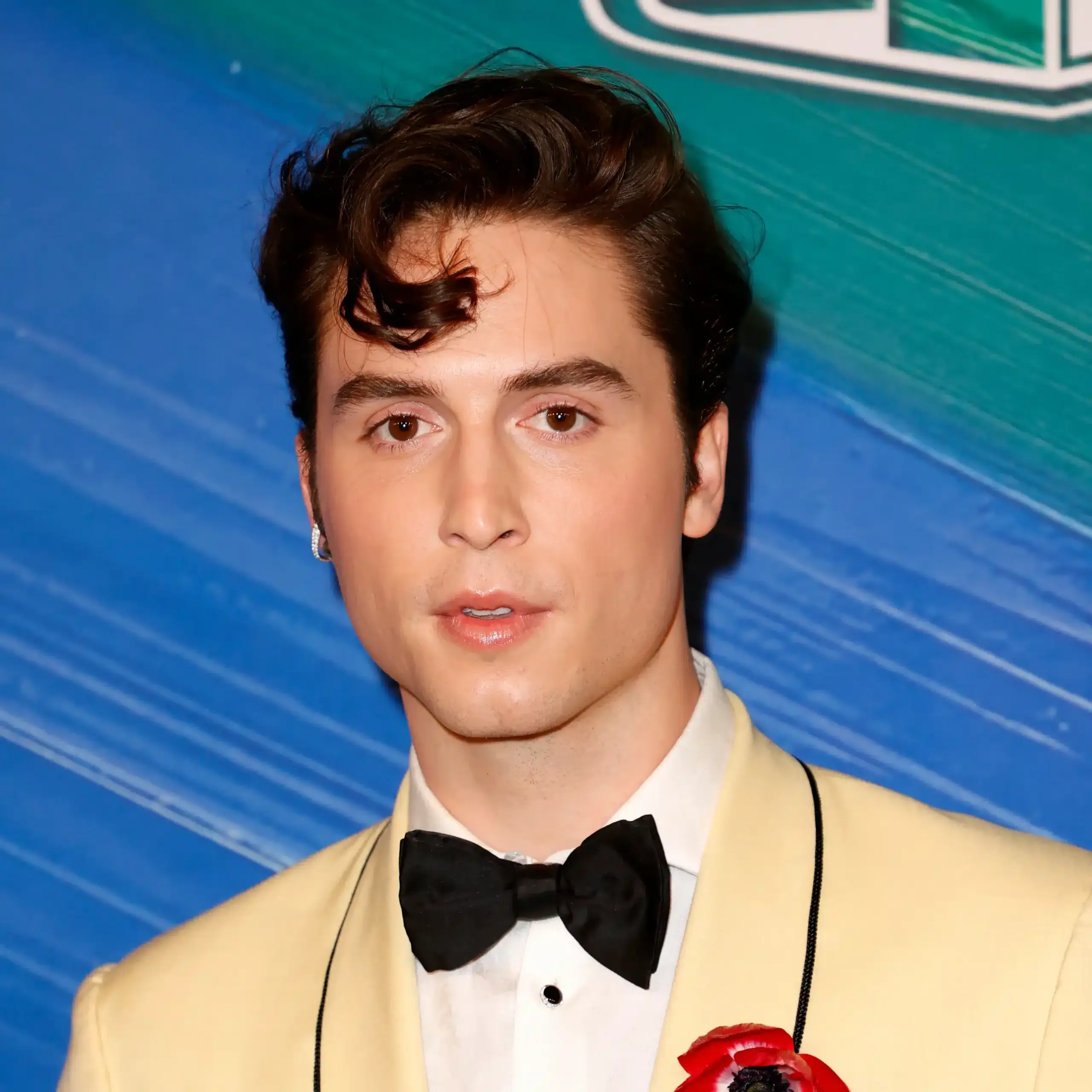

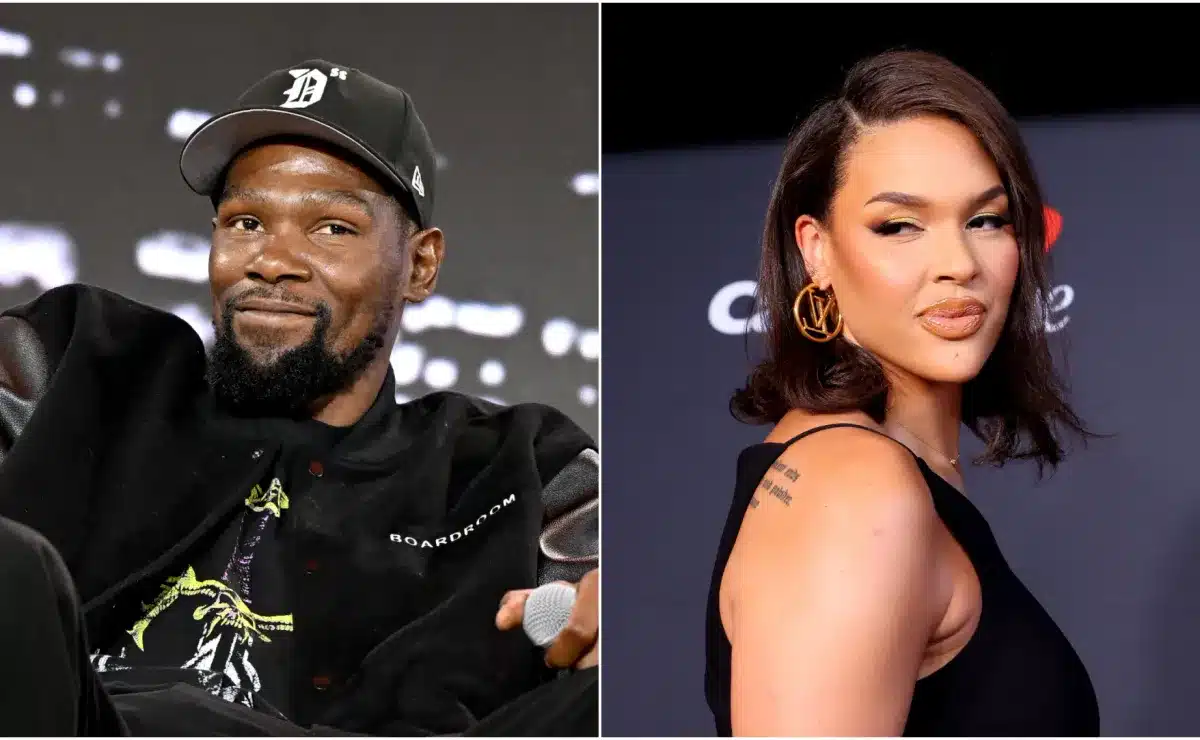

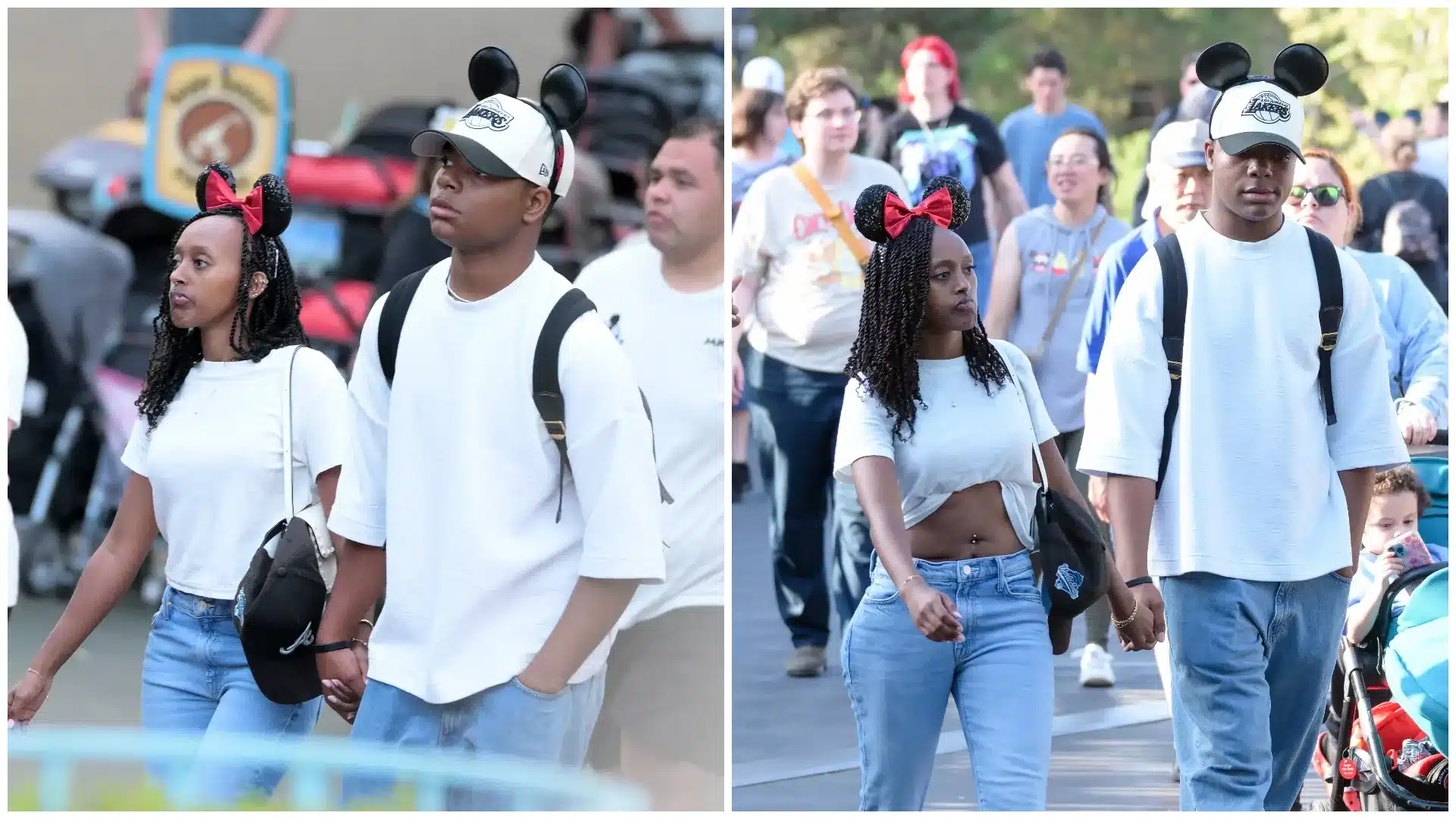

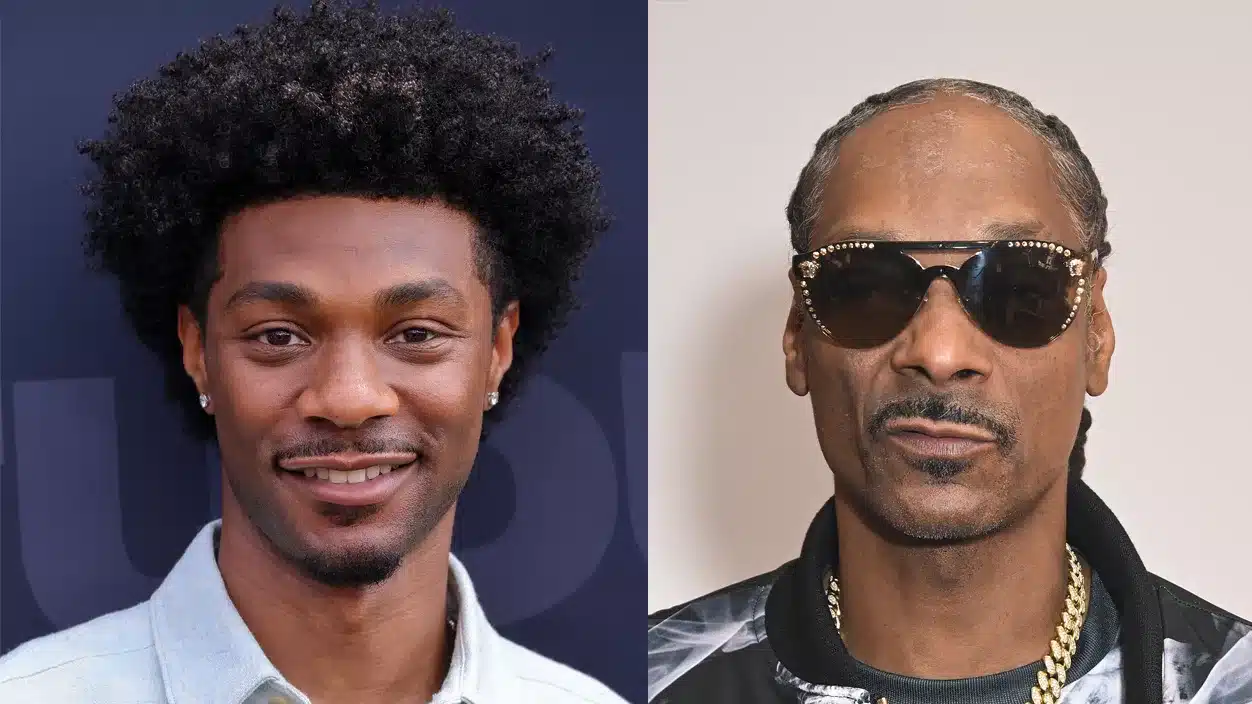

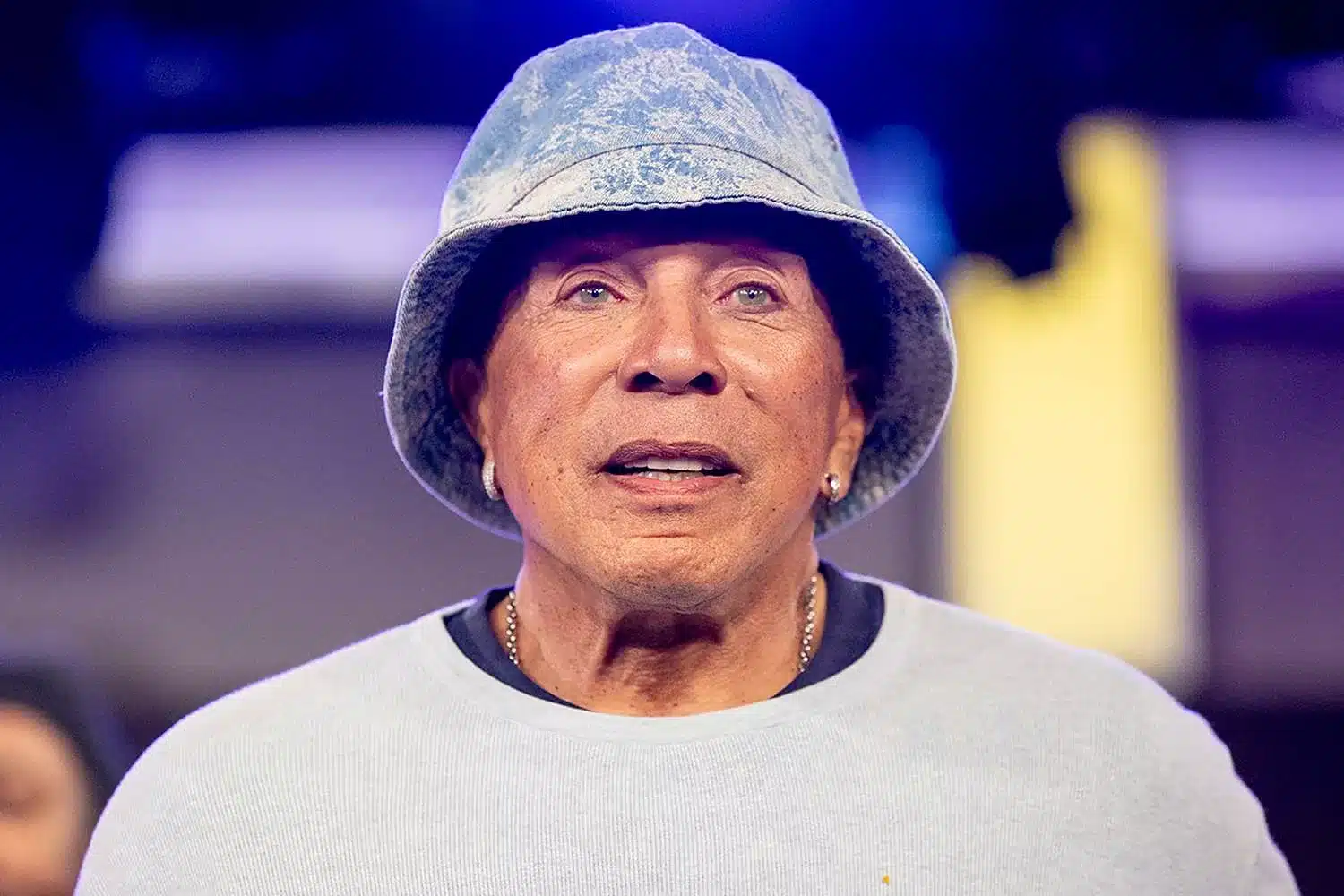

Cameron Cade (Tyriq Withers) is the next-generation college quarterback who is next in line to follow Marlon Wayans’s Isaiah White, the Tom Brady-type legend of this alternate world. But when a head injury threatens Cameron’s multimillion-dollar future, he goes to Isaiah’s desert compound to rehabilitate and prepare. The location soon turns into a haunted house of depravity, duplicity, and mental abuse, capable of engulfing Cameron.

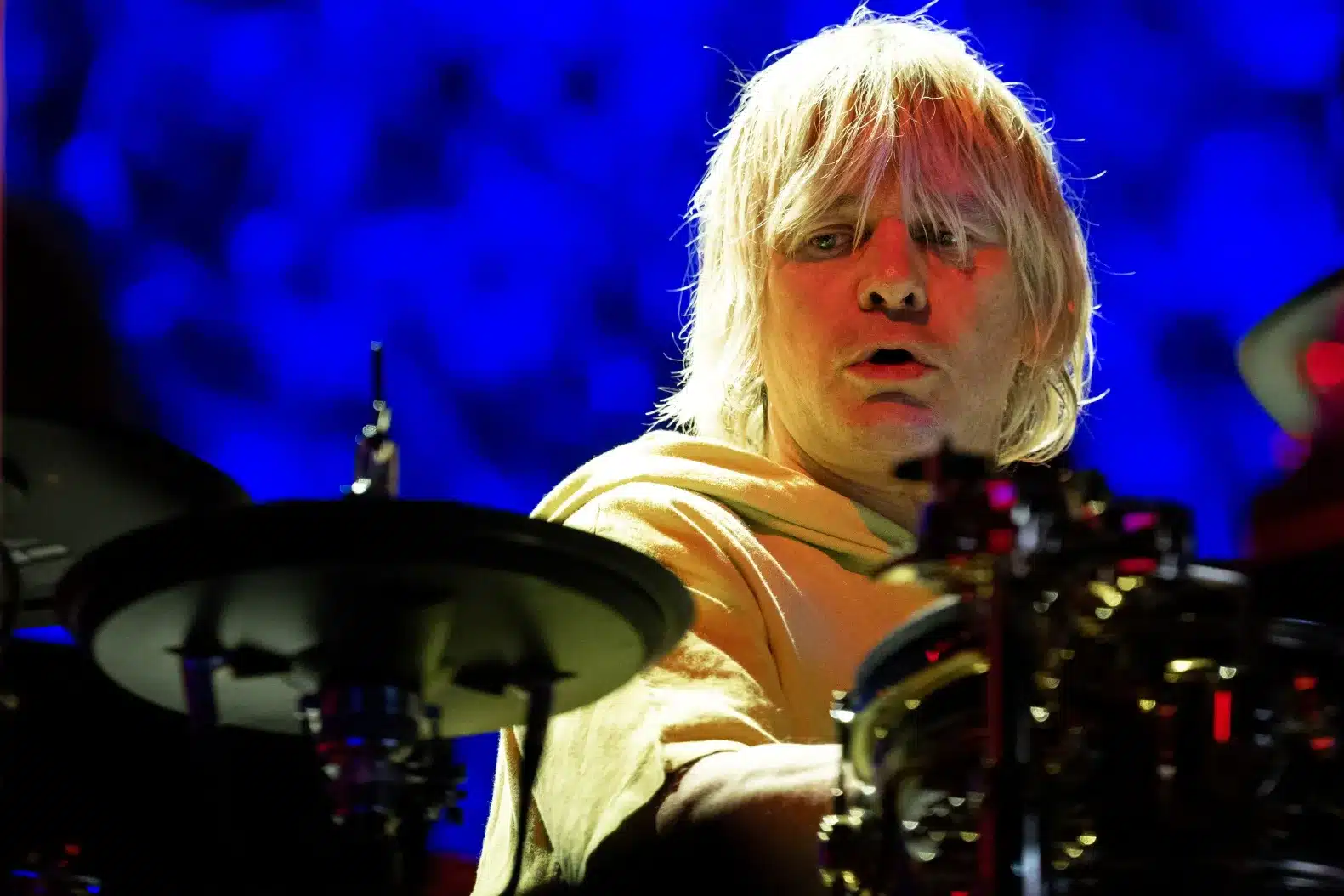

From its beginning, Him declares itself a hard-hitting critique of football culture. The first scene shows Isaiah shattering his leg during a championship drive, with young Cameron observing the nasty injury as his father pounds the words “no guts, no glory” into him. It is not a subtle criticism – football is presented as a veritable meat grinder where players are made into commodities, parsed like chattel. Tipping even uses X-ray vision imagery to highlight the unseen destruction from constant crashes.

But where the film tries to be daring, it is undermined by unfeasibility. In racing movies like F1, American viewers can abridge reality. In football, though, its realities are too well-entrenched in American society. People recognize quarterbacks hold a privileged niche, and the idea of a prospect like Cameron going through the same brutal ordeals as journeymen wide receivers or defensive linemen stretches credulity.

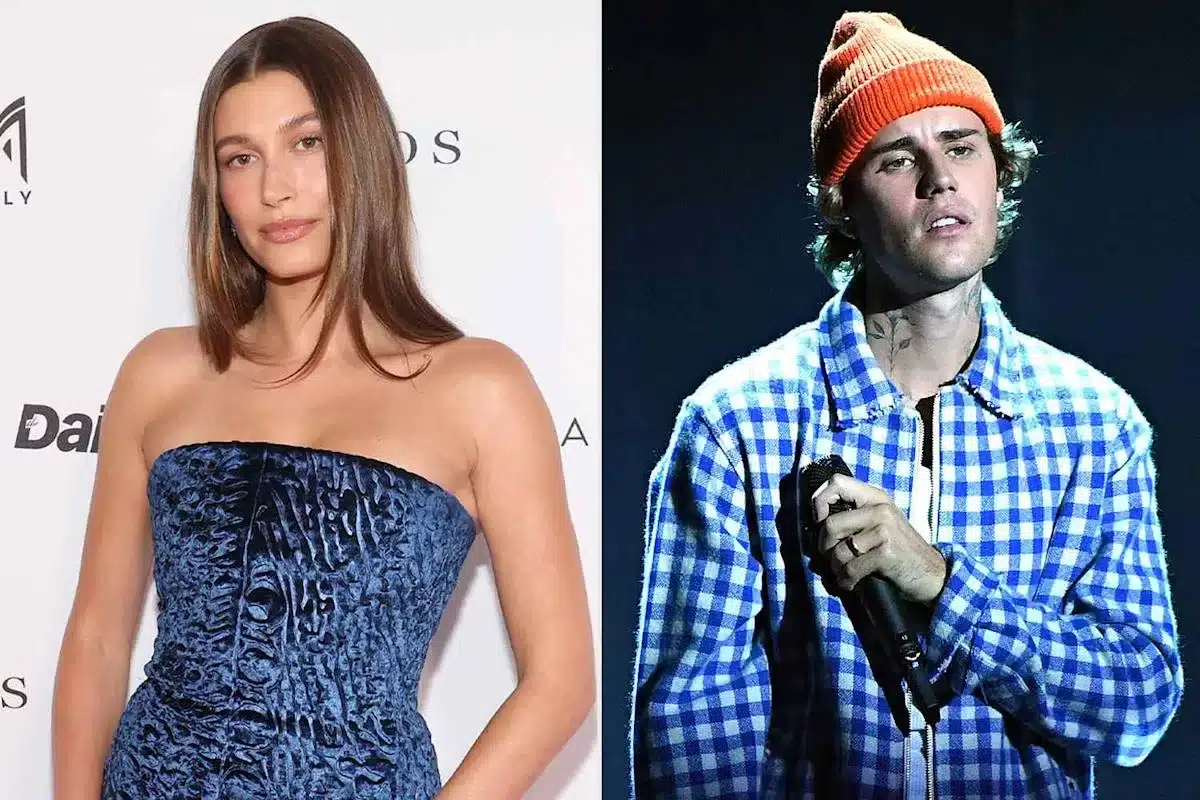

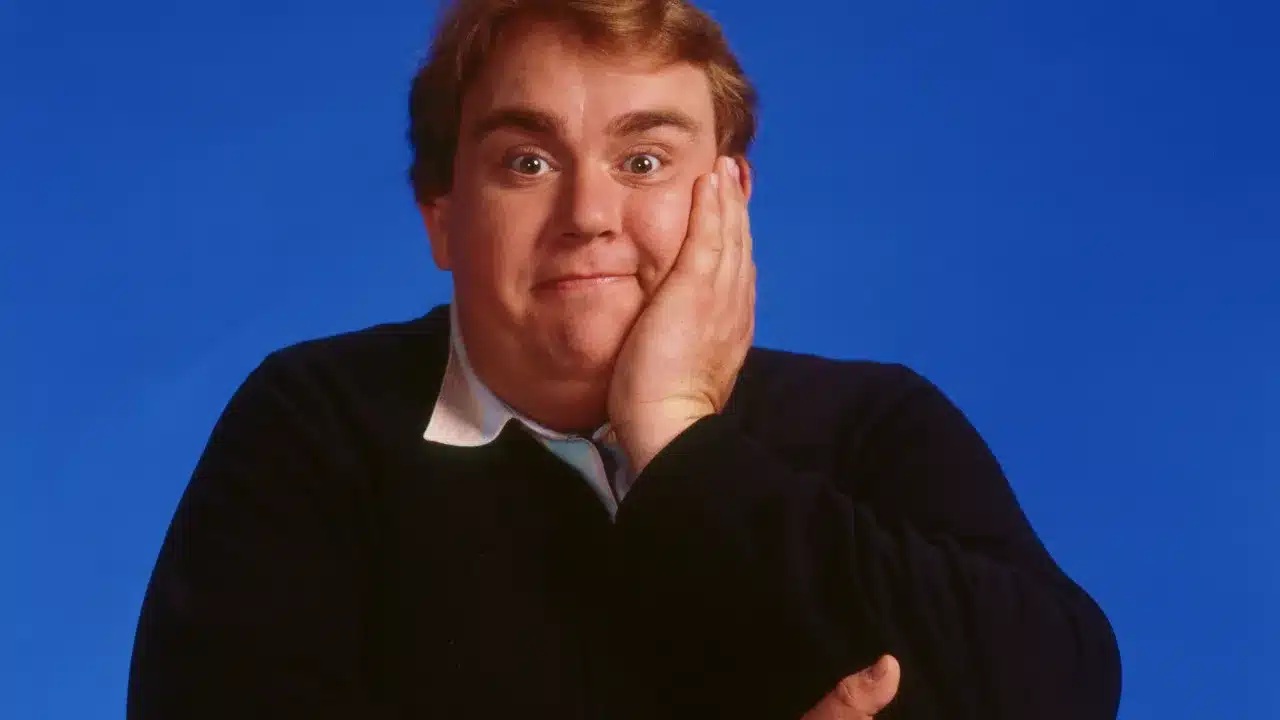

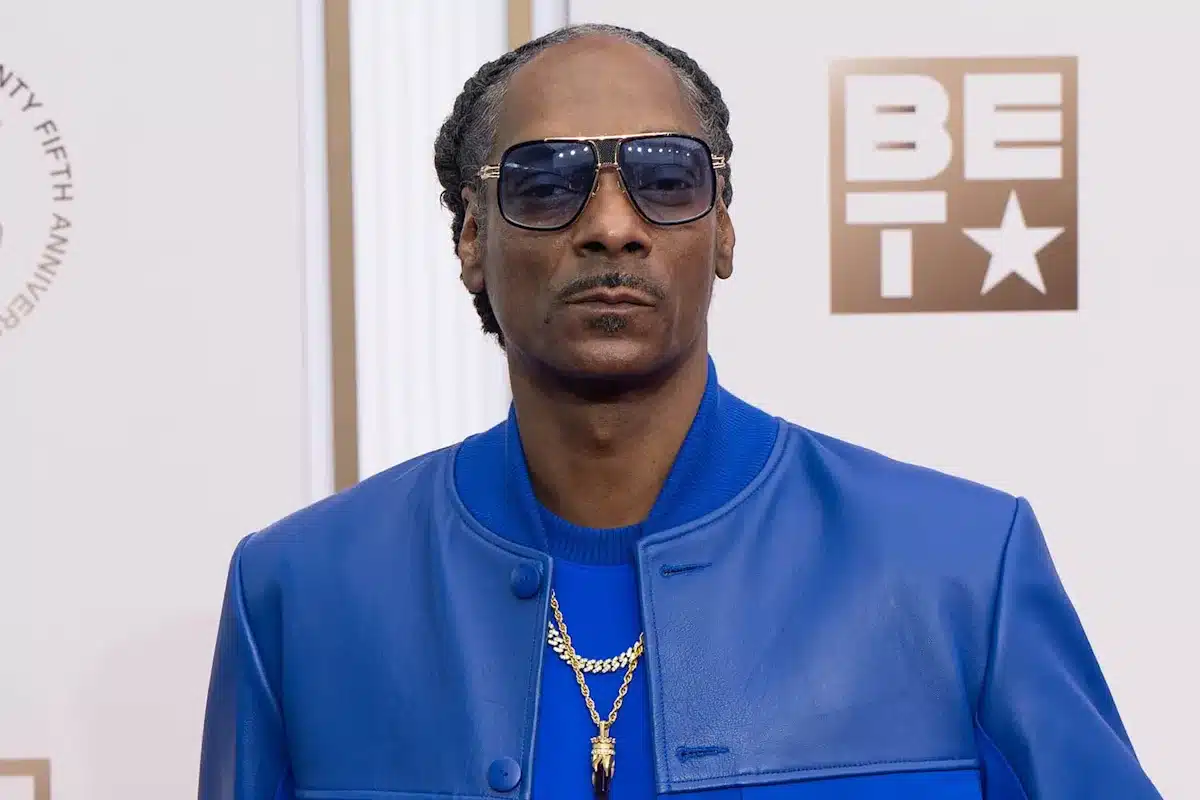

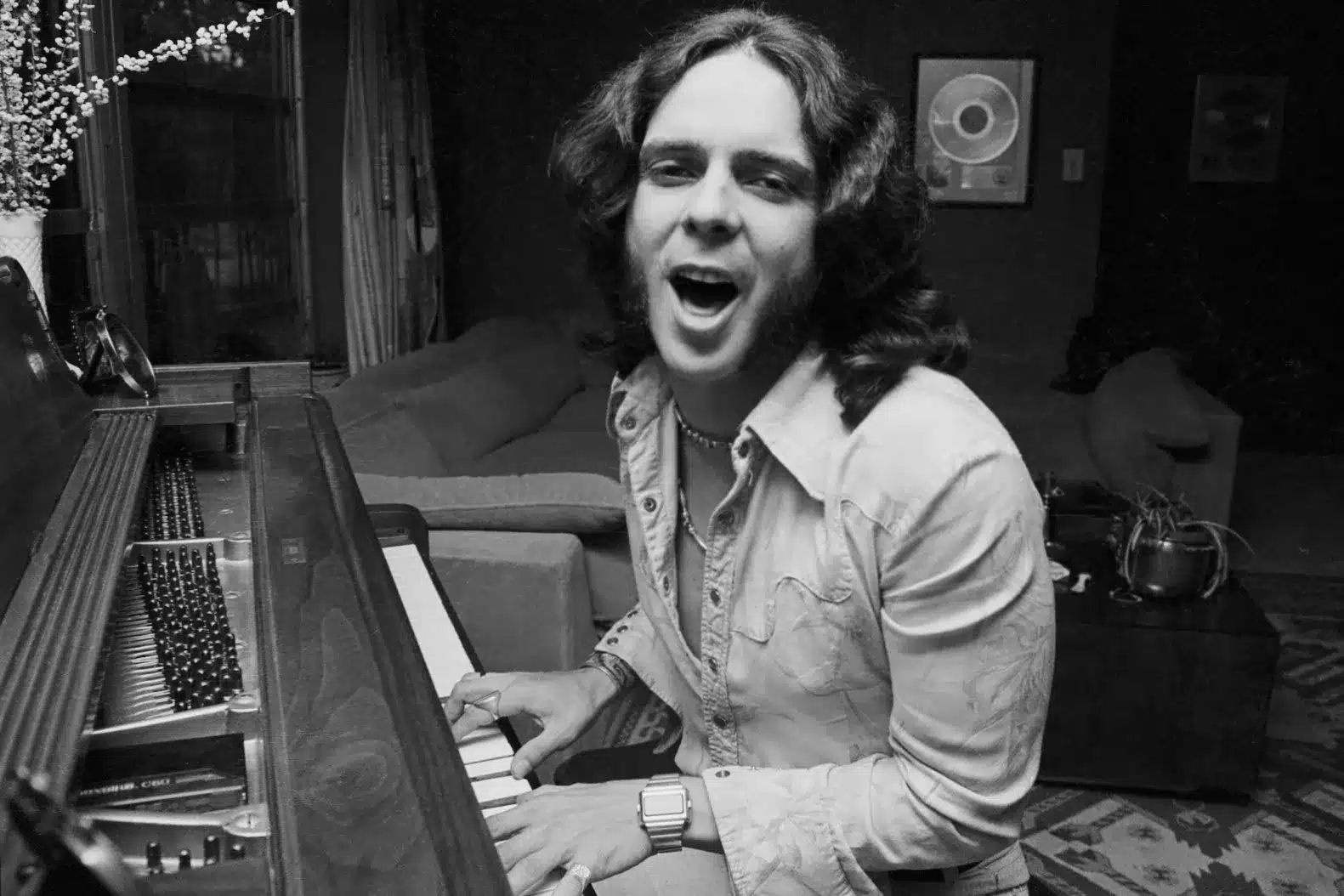

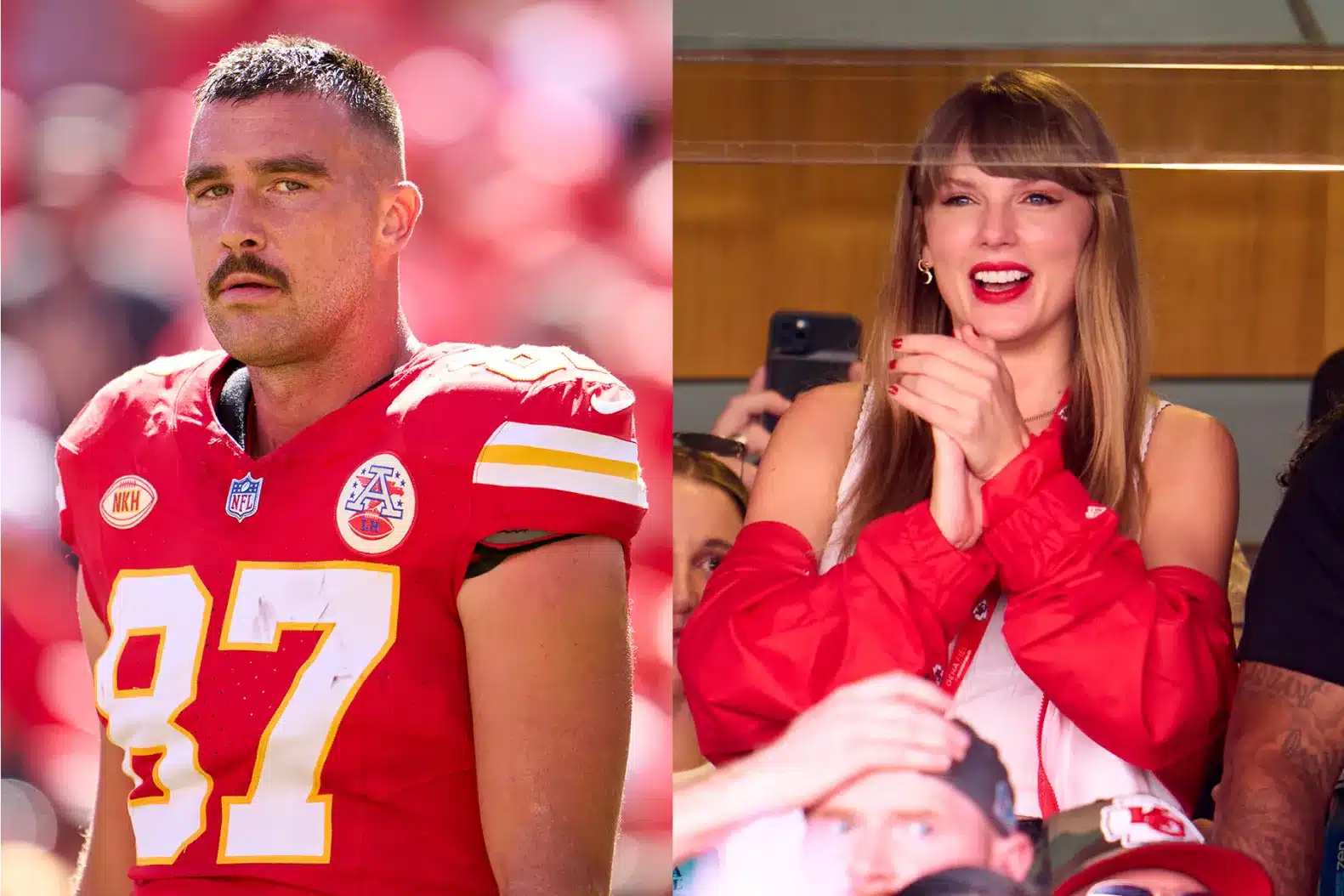

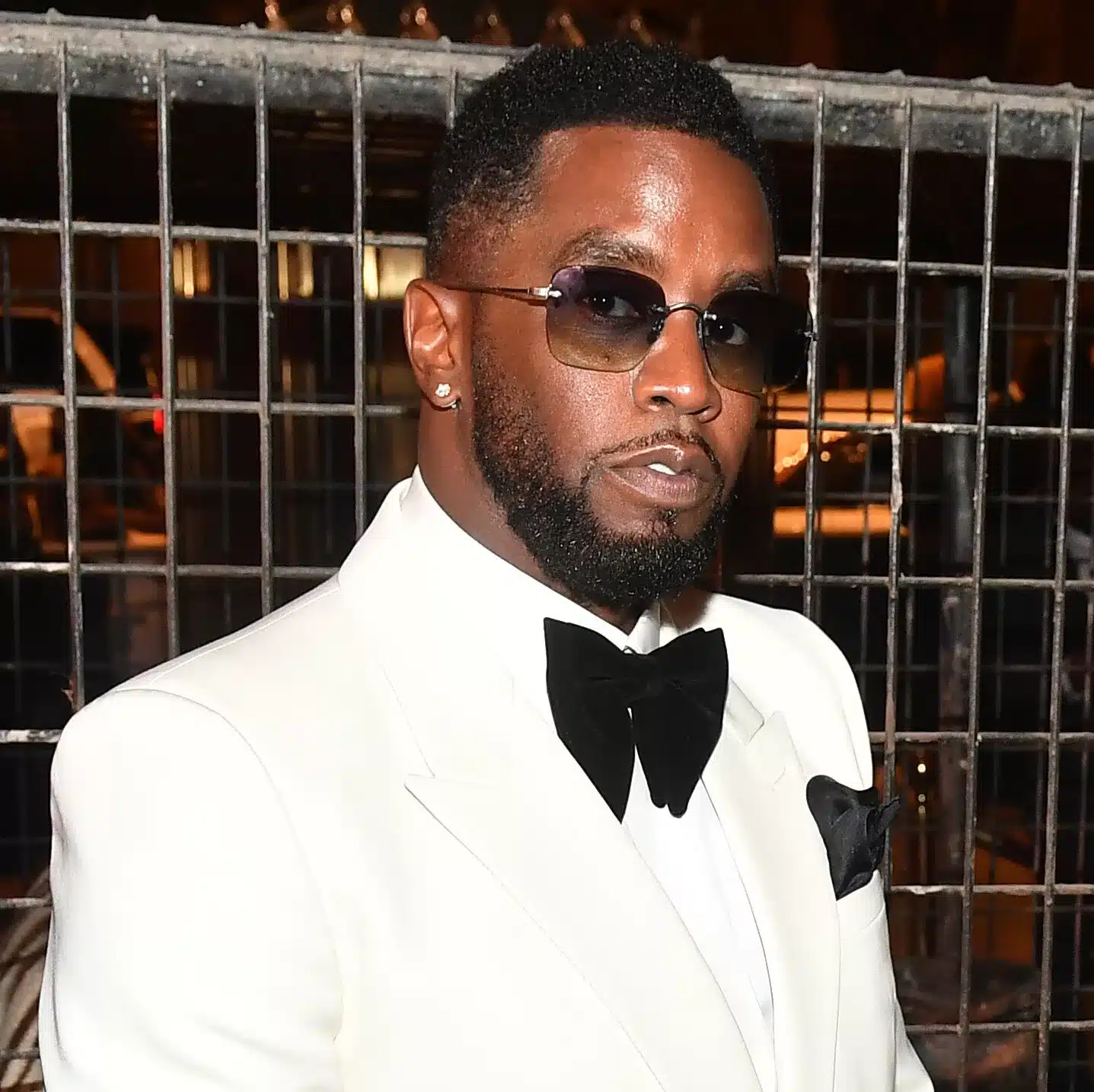

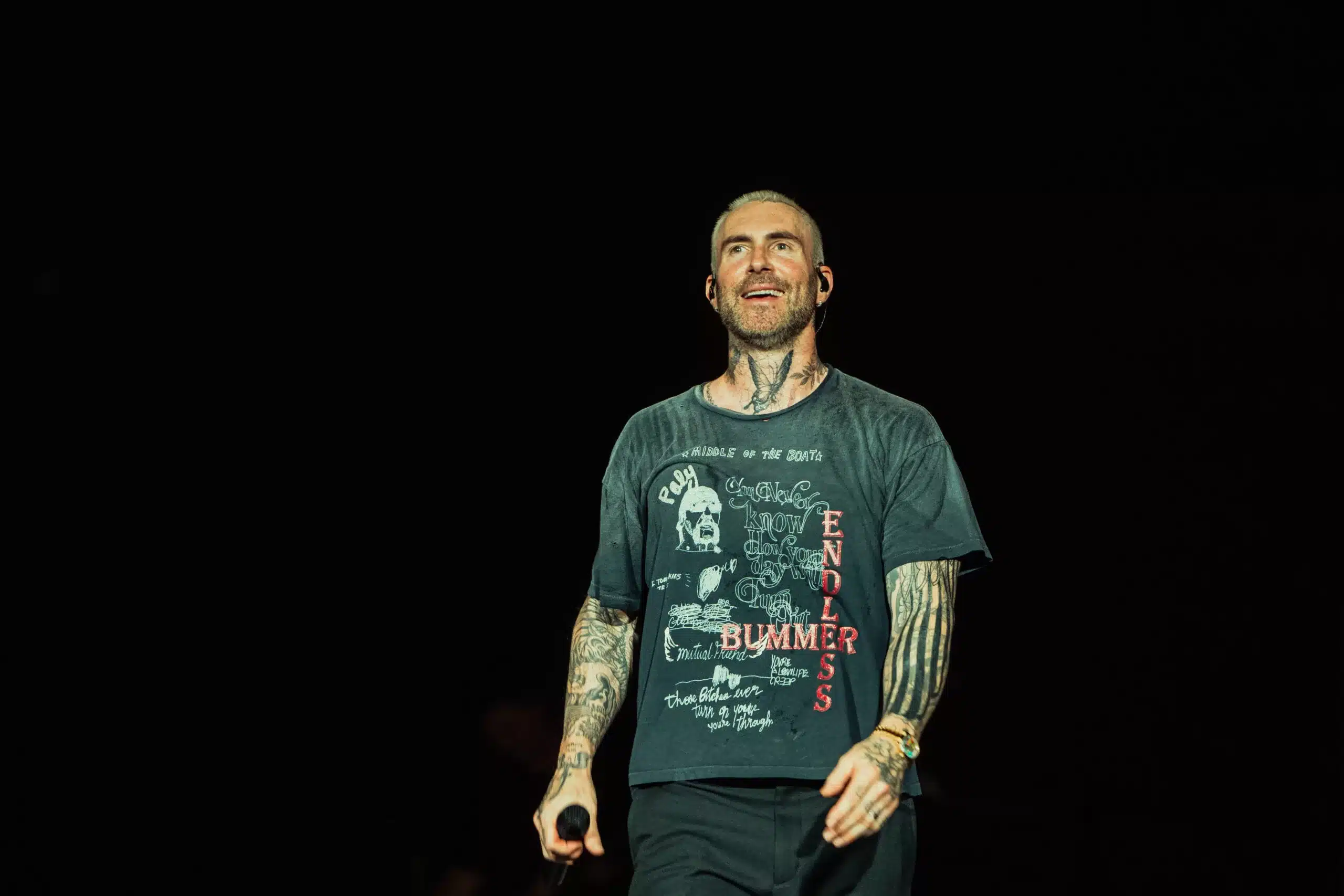

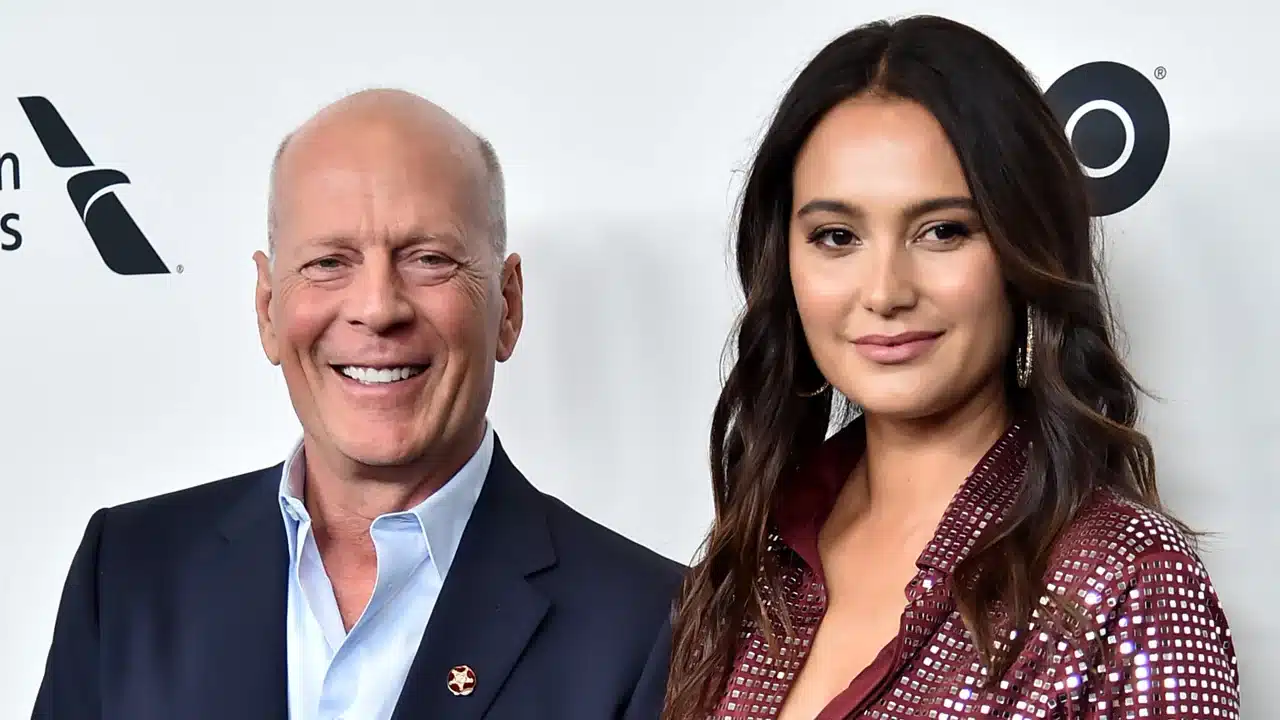

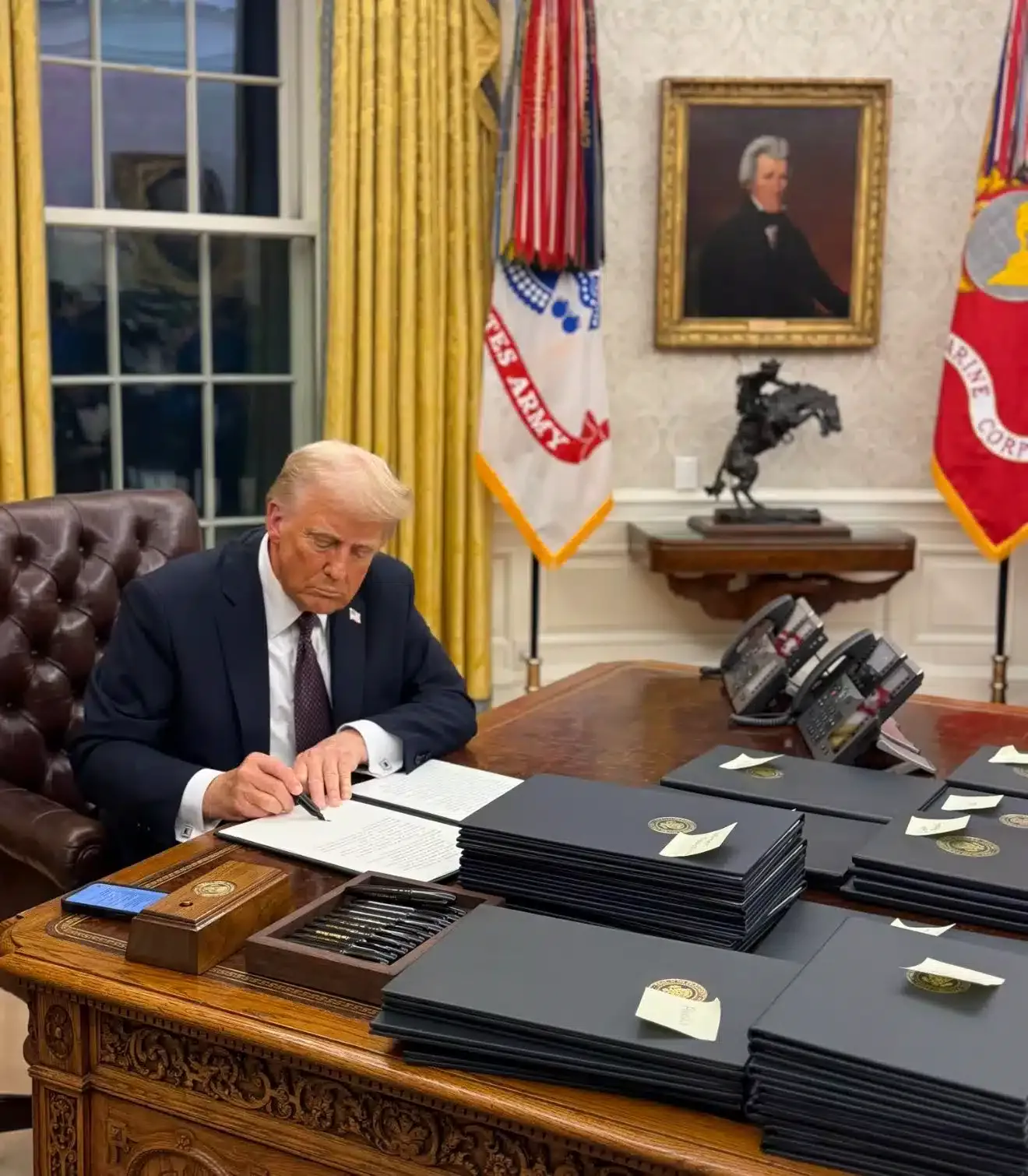

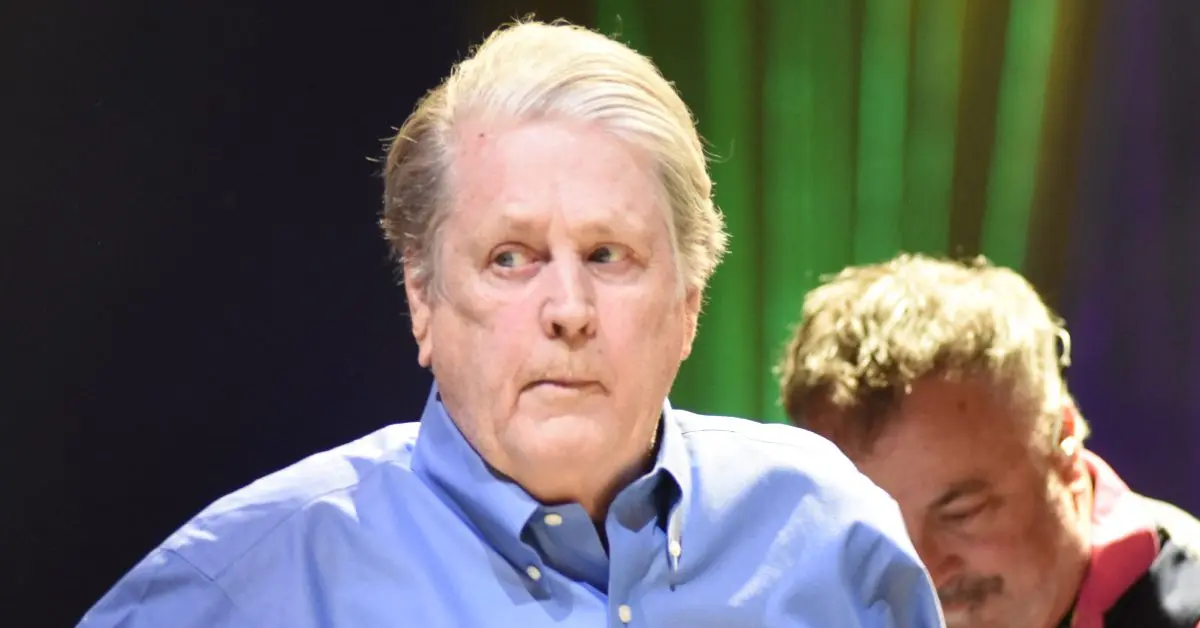

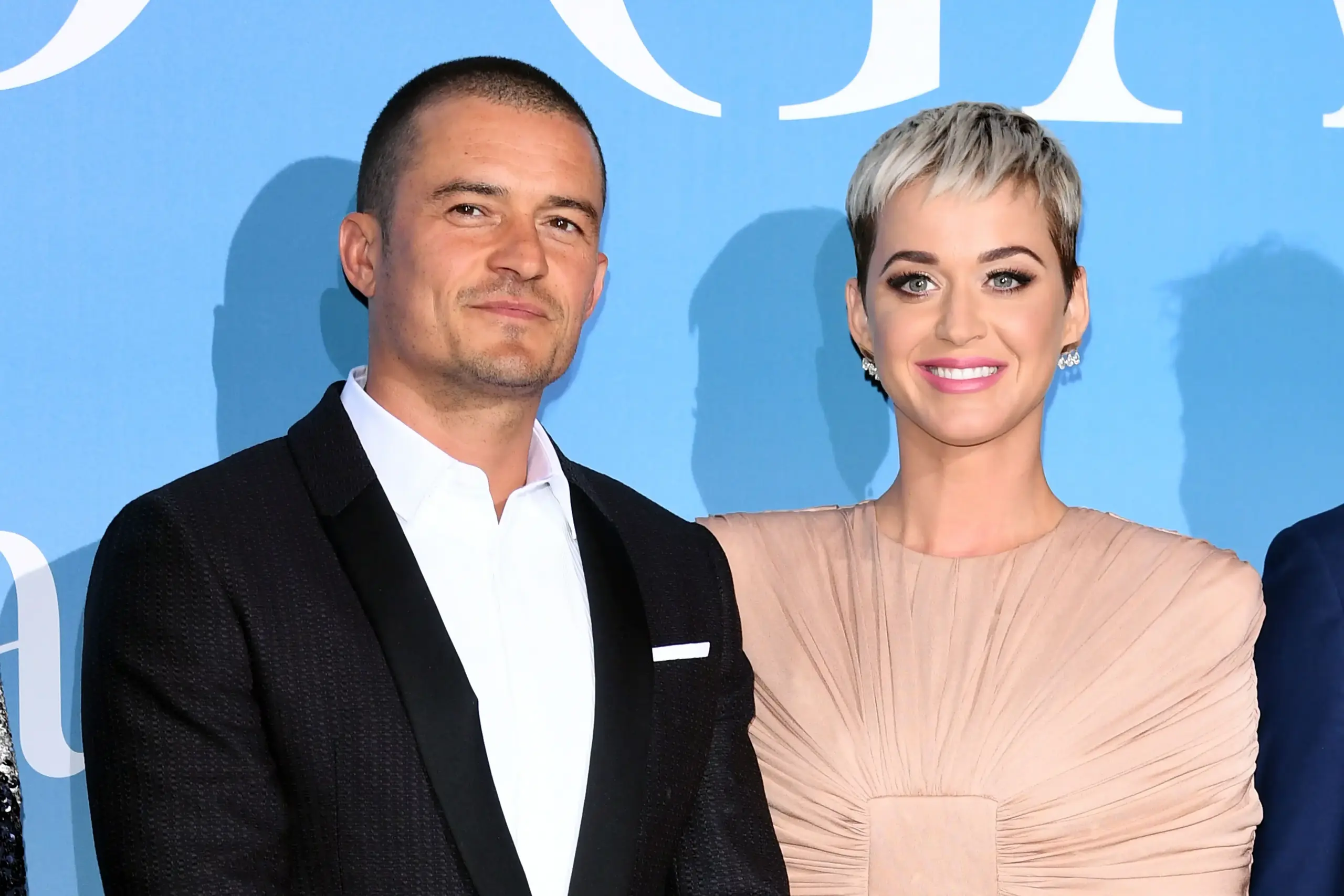

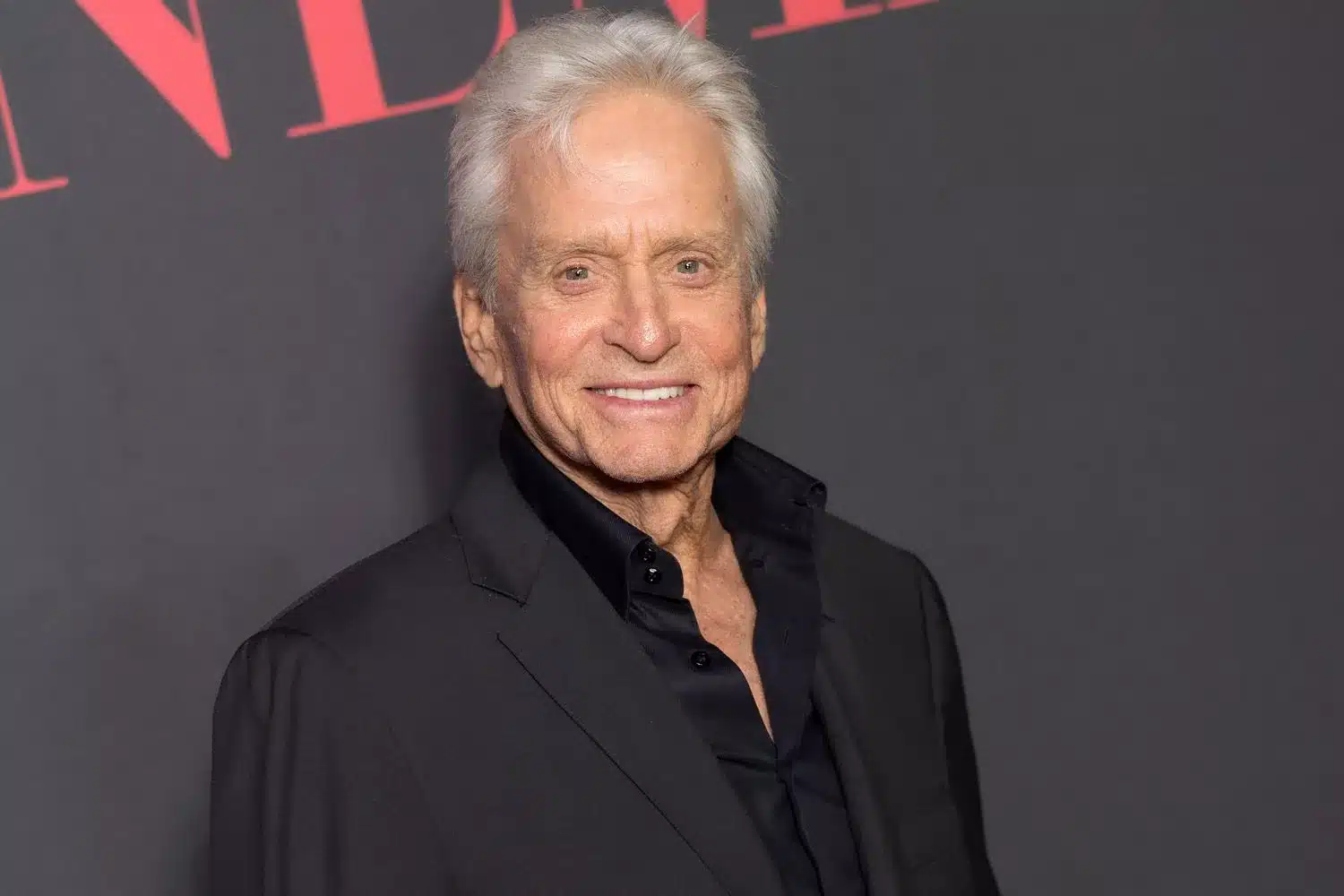

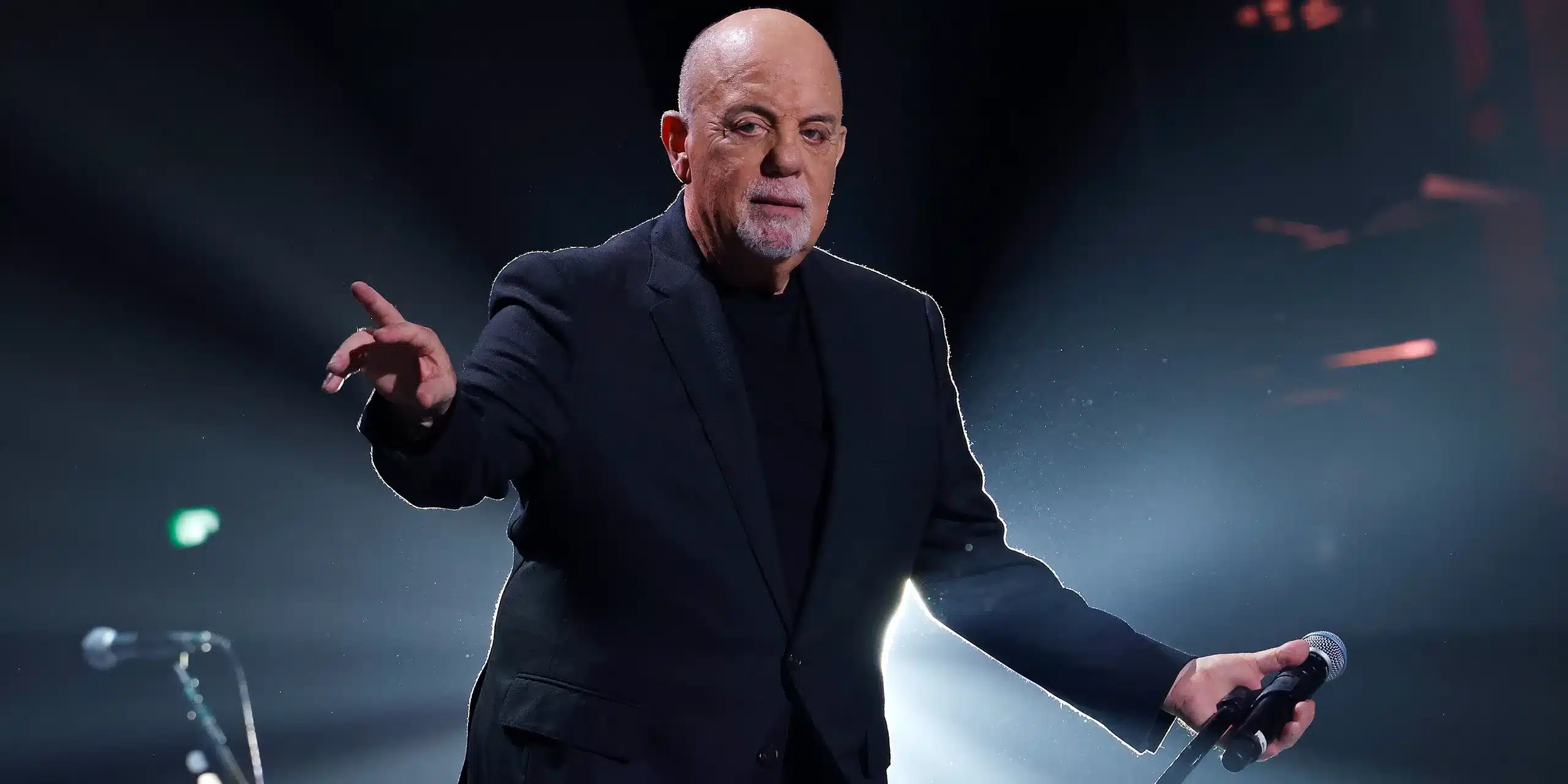

The casting selection doesn’t assist. Wayans, who is now 53, doesn’t quite work as an aging football legend still hanging on to his profession as well as tutoring the next superstar. Having him pay for a massive desert training facility seems like something more reserved for baseball players, where deals are secure. The scouting combine scene, previously a necessary proving ground, also seems passé – contemporary top quarterbacks increasingly opt out of it altogether. And whereas true NFL legends such as Tom Brady once came into the league with humble physiques, Him is fixated on Cameron’s physique as if it were the only metric that mattered.

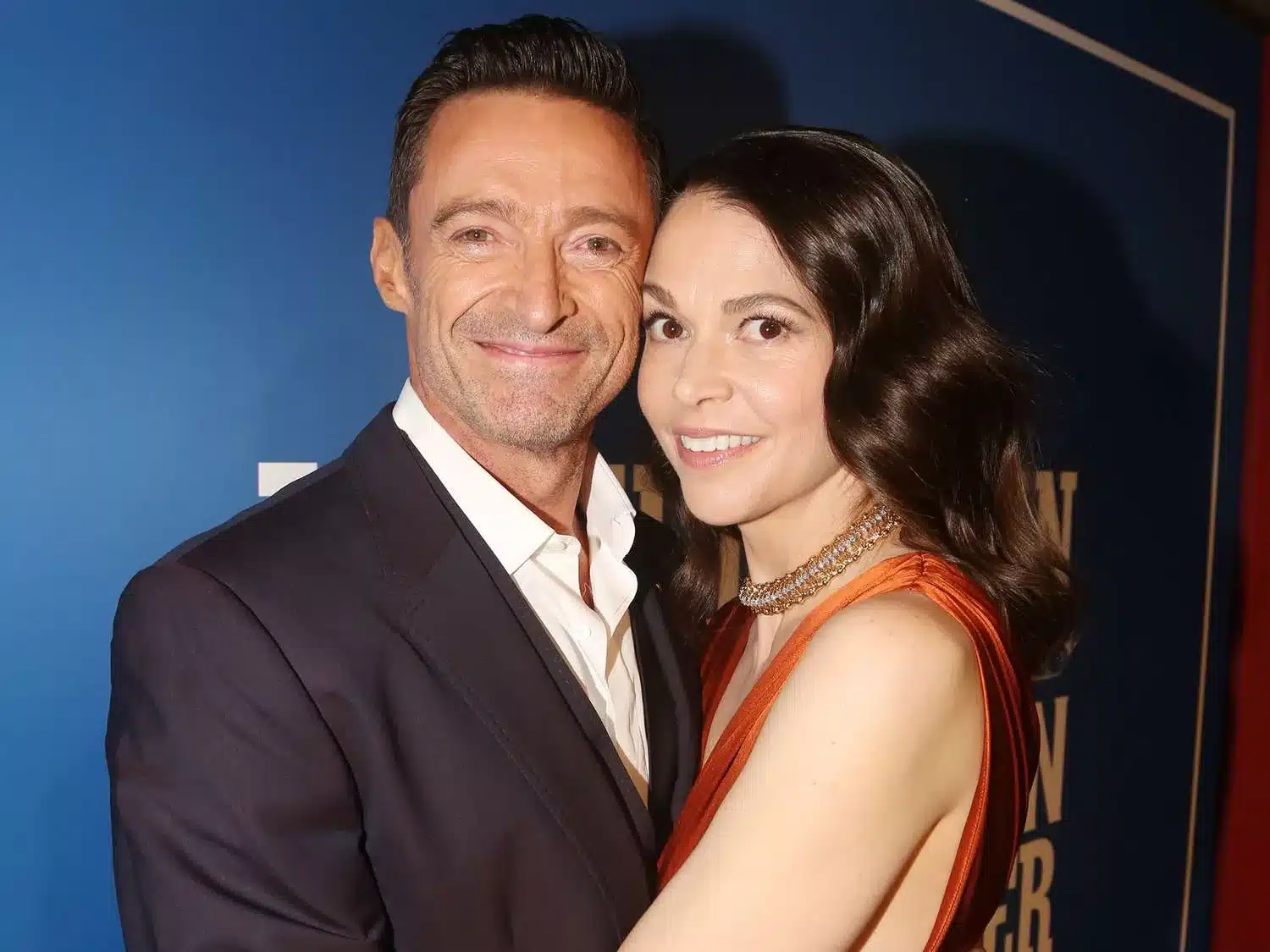

The protégé–mentor dynamic between Isaiah and Cameron falters upon close inspection. In real life, a quarterback struggling against Father Time would not be likely to spend his energy mentoring his successor. Oliver Stone’s Any Given Sunday developed this tension much more convincingly, basing its criticism of the brutality of professional football on plausible character dynamics. Him stumbles into melodramatic hyperbole instead, leaving its football commentary confused.

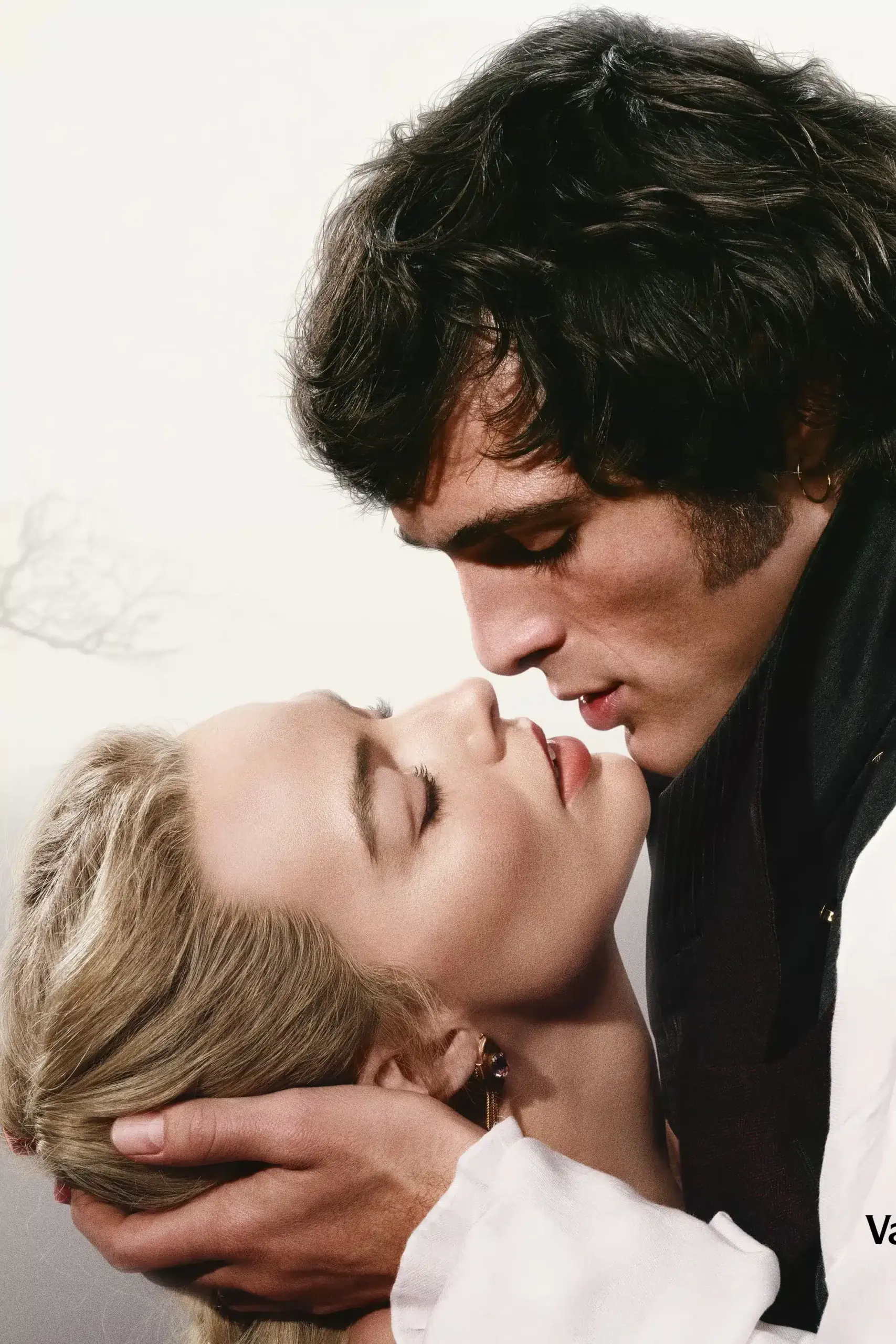

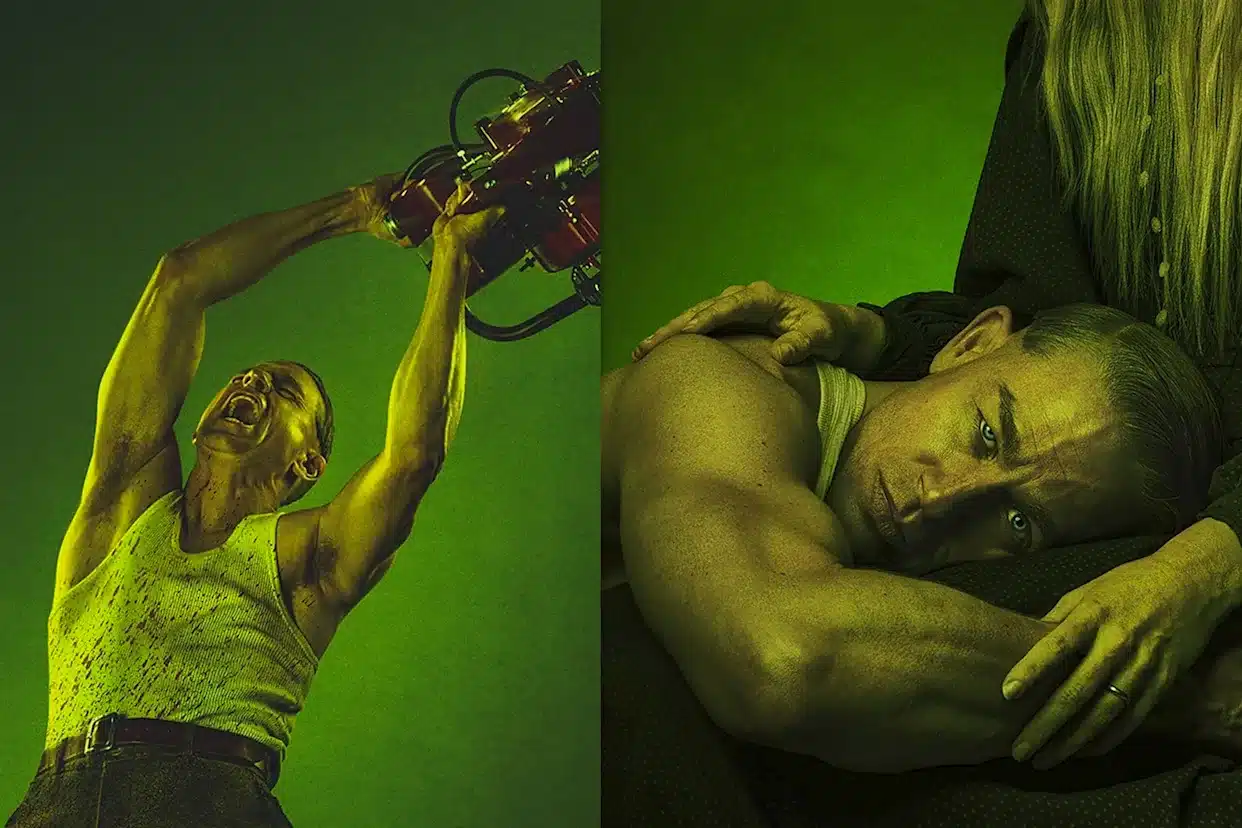

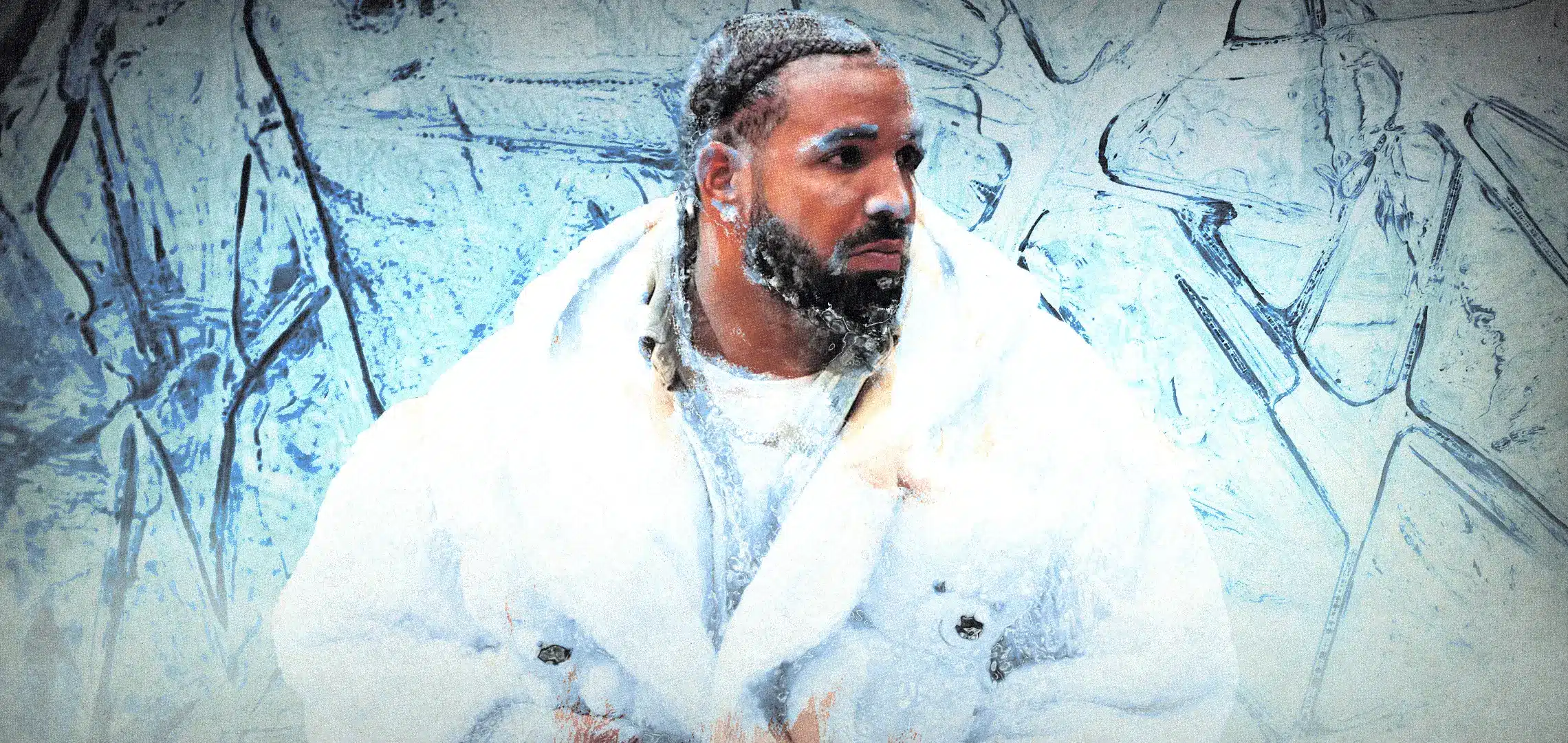

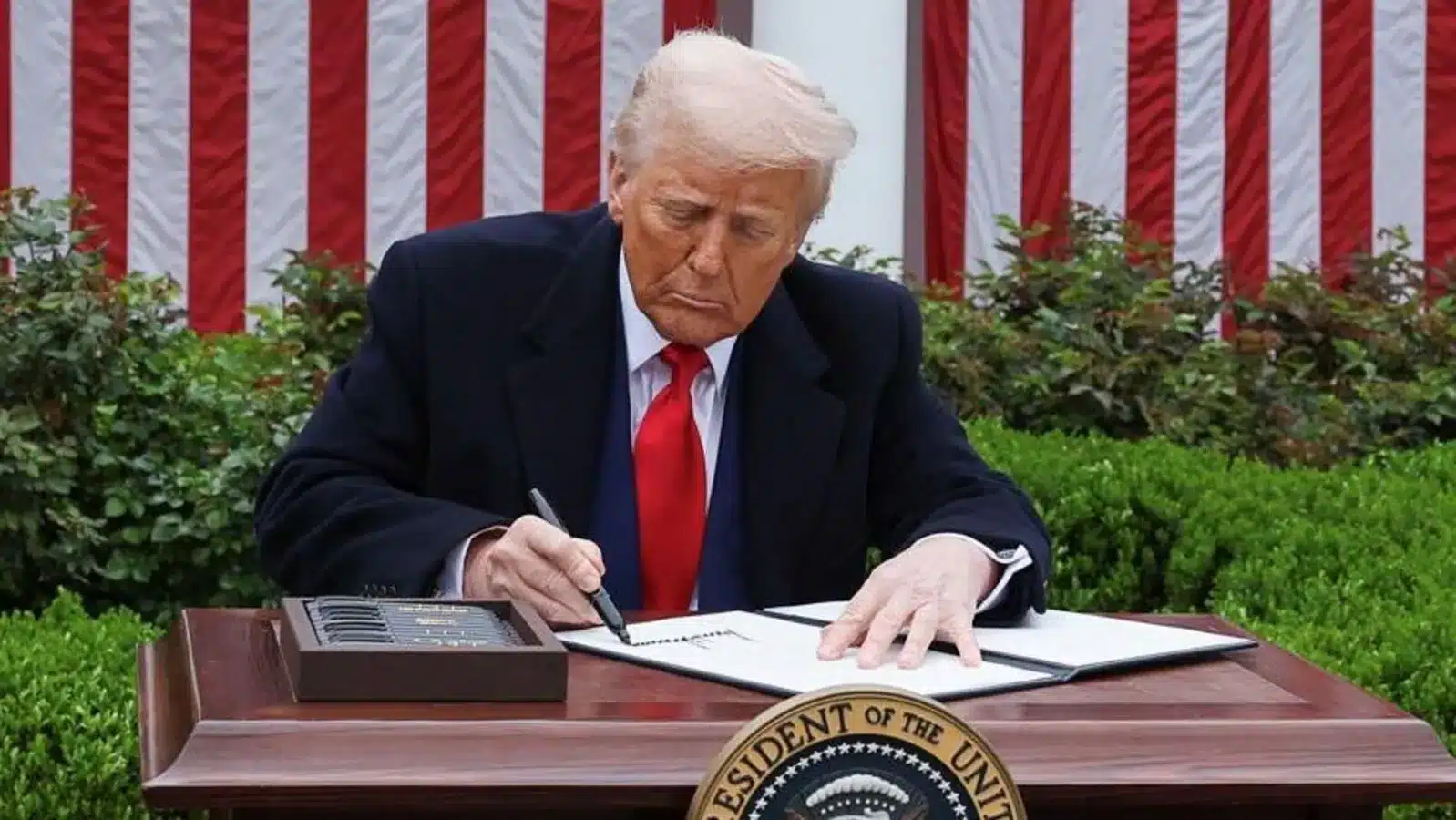

Yet, Tipping and his co-authors try to raise the movie with daring thematic hooks. They position football as a sort of pagan cult, mixing Christian imagery with satanic symbolism. Isaiah rails against worshipping the sport instead of God, saying to Cameron, “He died for us so I play for Him.” The team is actually named the Saviors, and Isaiah’s picture hangs among Cameron’s trophies like a saccharine relic. The movie invokes the acronym GOAT (greatest of all time) as if it were a sacramental name, interweaving visions of blood rituals and sacred sacrifice.

One notably transgressive moment – a Last Supper-like photoshoot with Cameron standing in for Jesus – apparently caused walkouts during its Atlanta preview. For God-fearing soccer supporters, ostensibly the film’s natural audience, such depictions threatens outright alienation. Rather than playing as satire, the series comes across as heavy-handed and alienates far more than it informs.

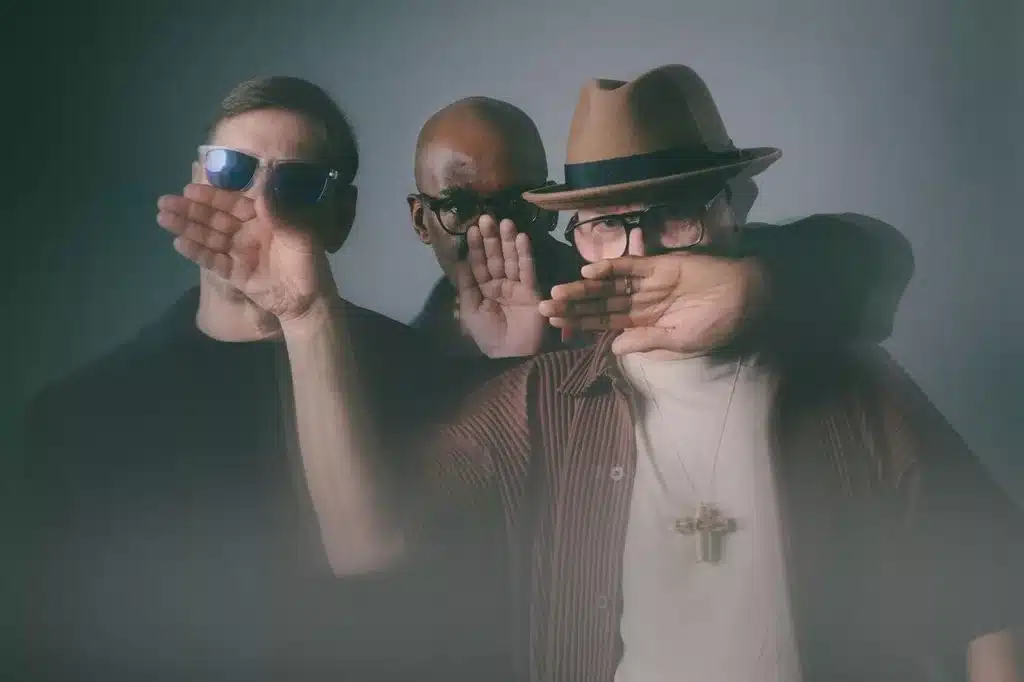

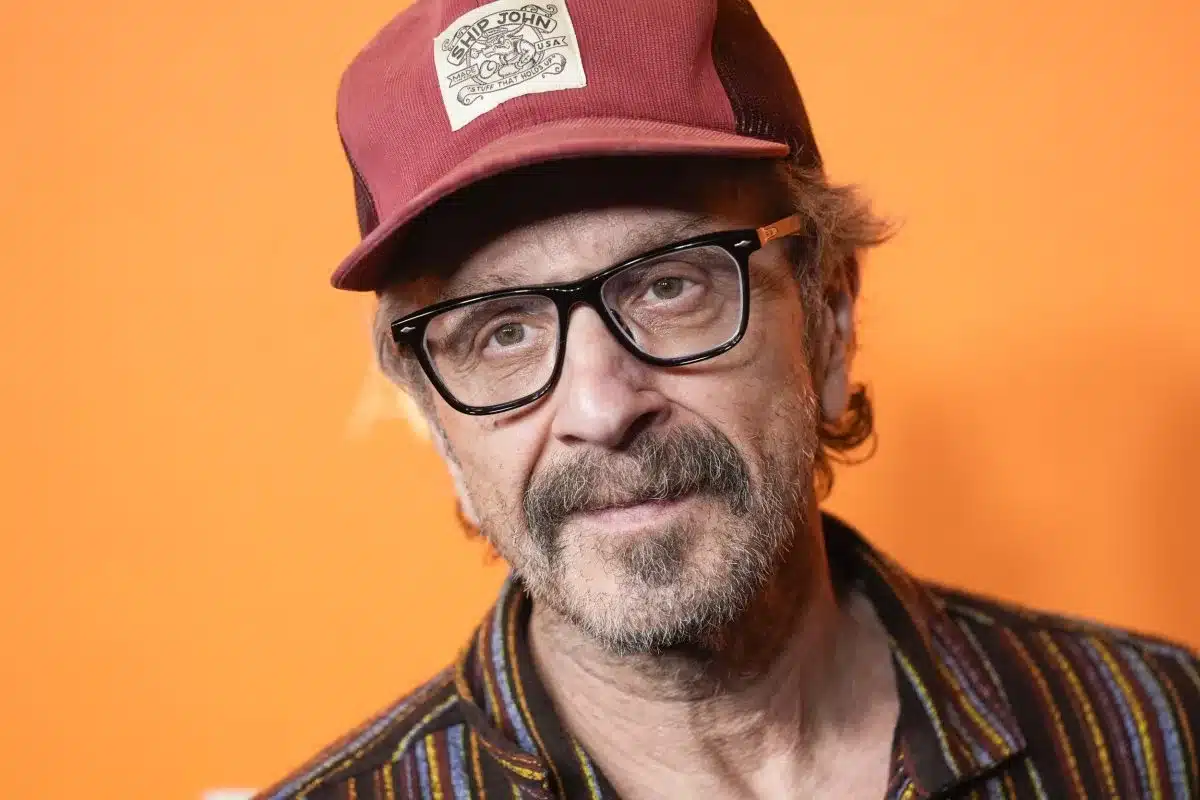

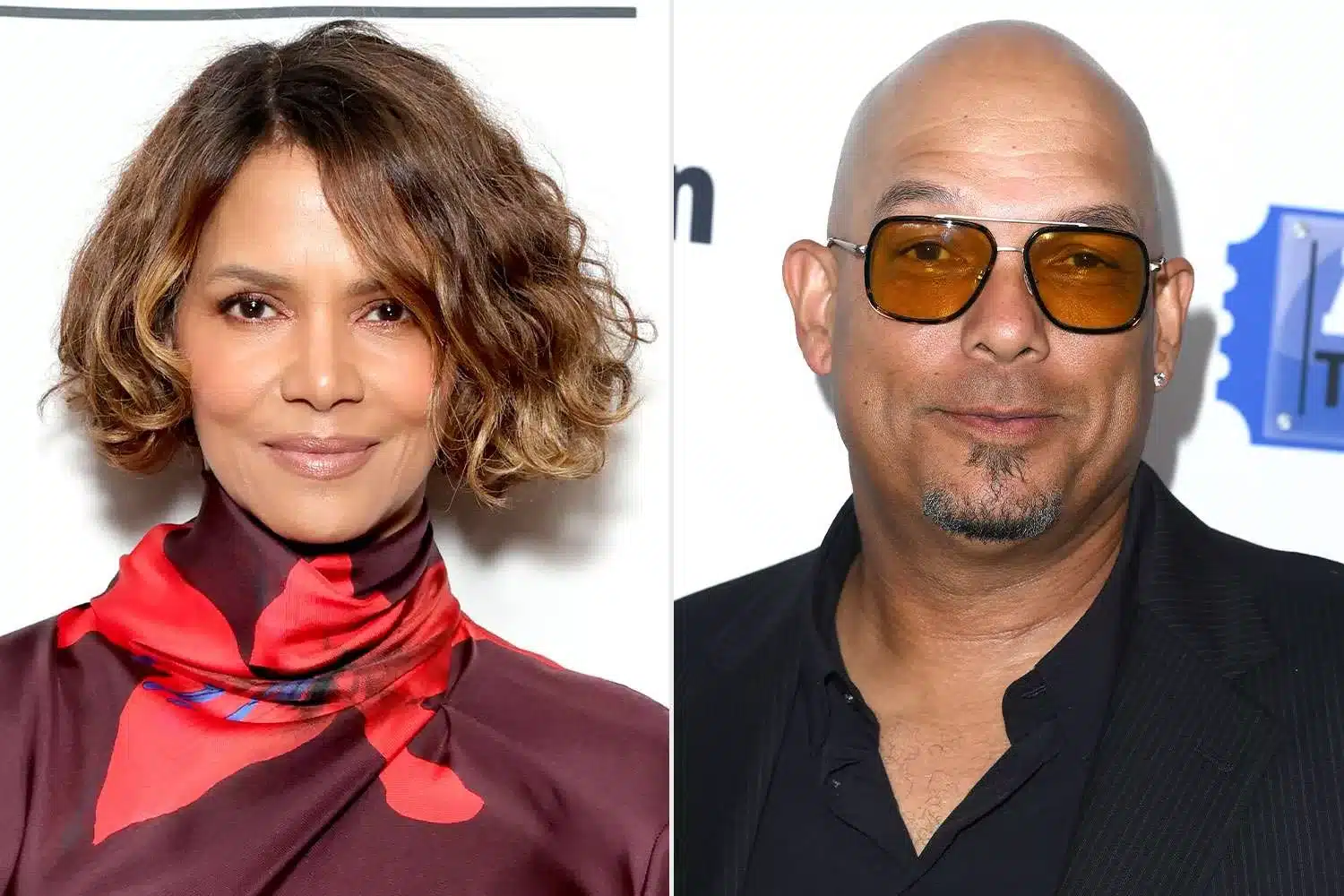

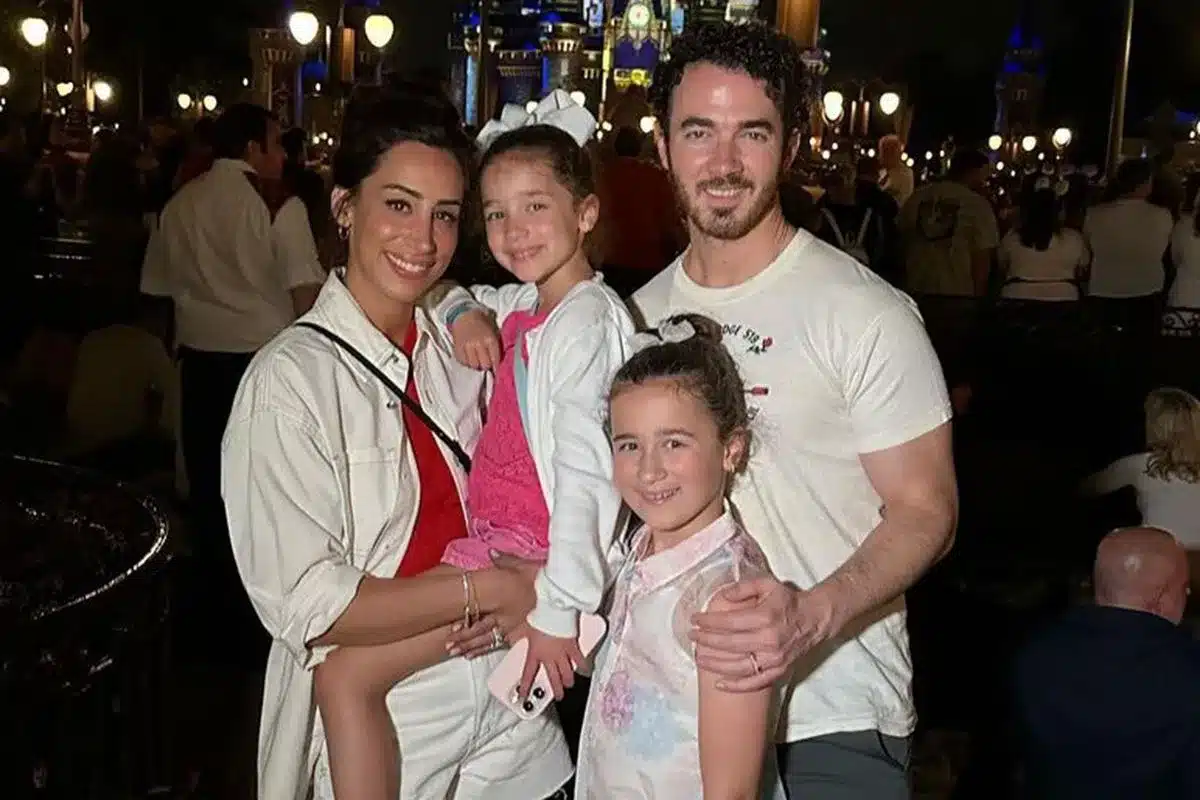

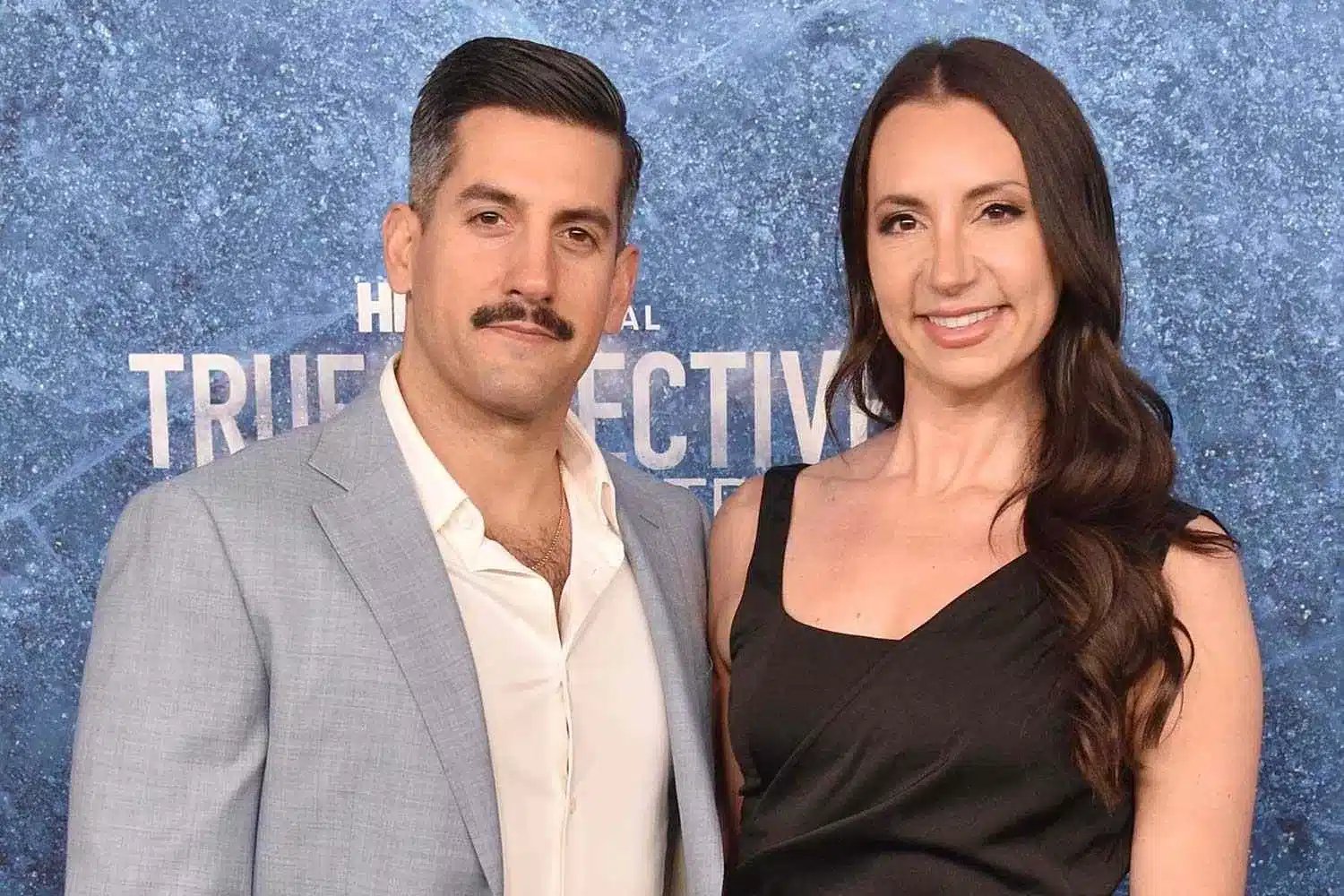

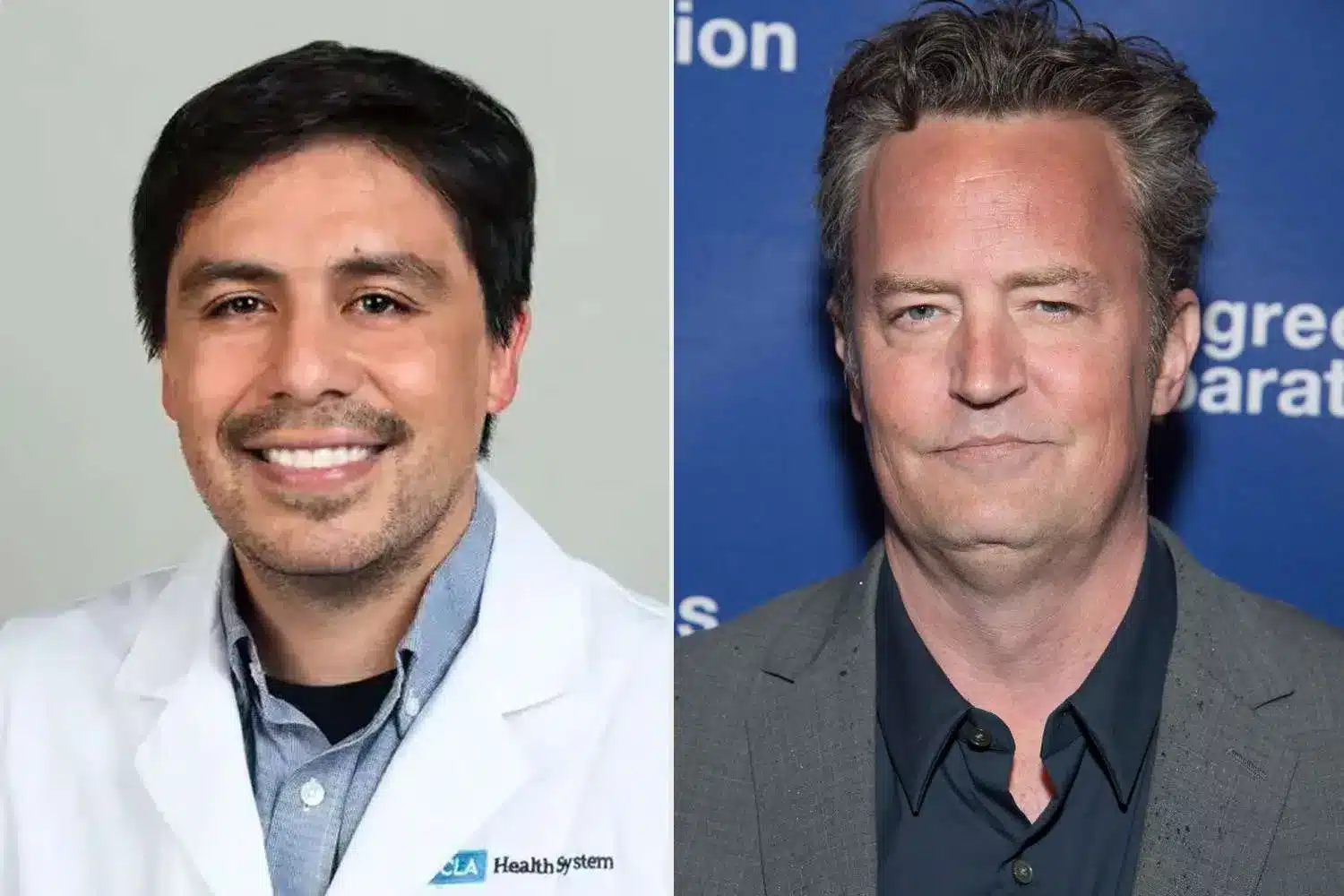

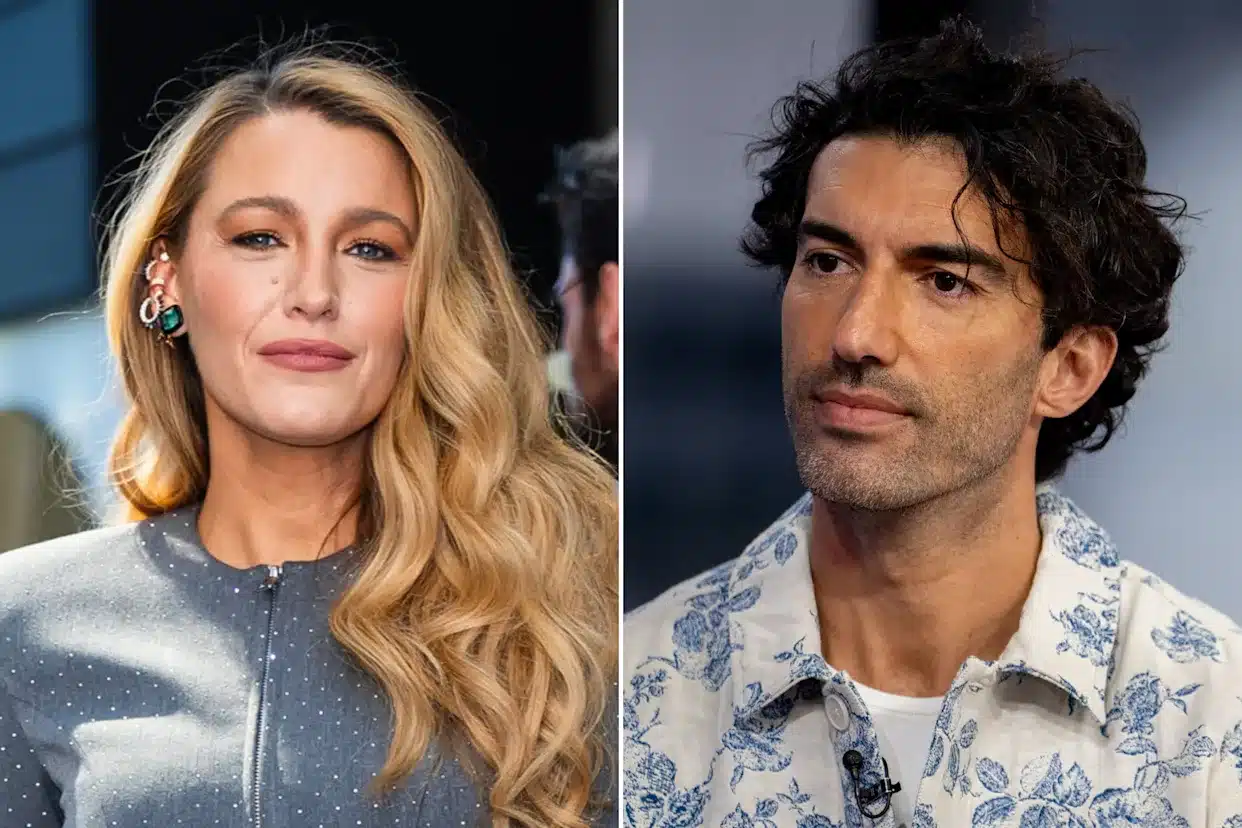

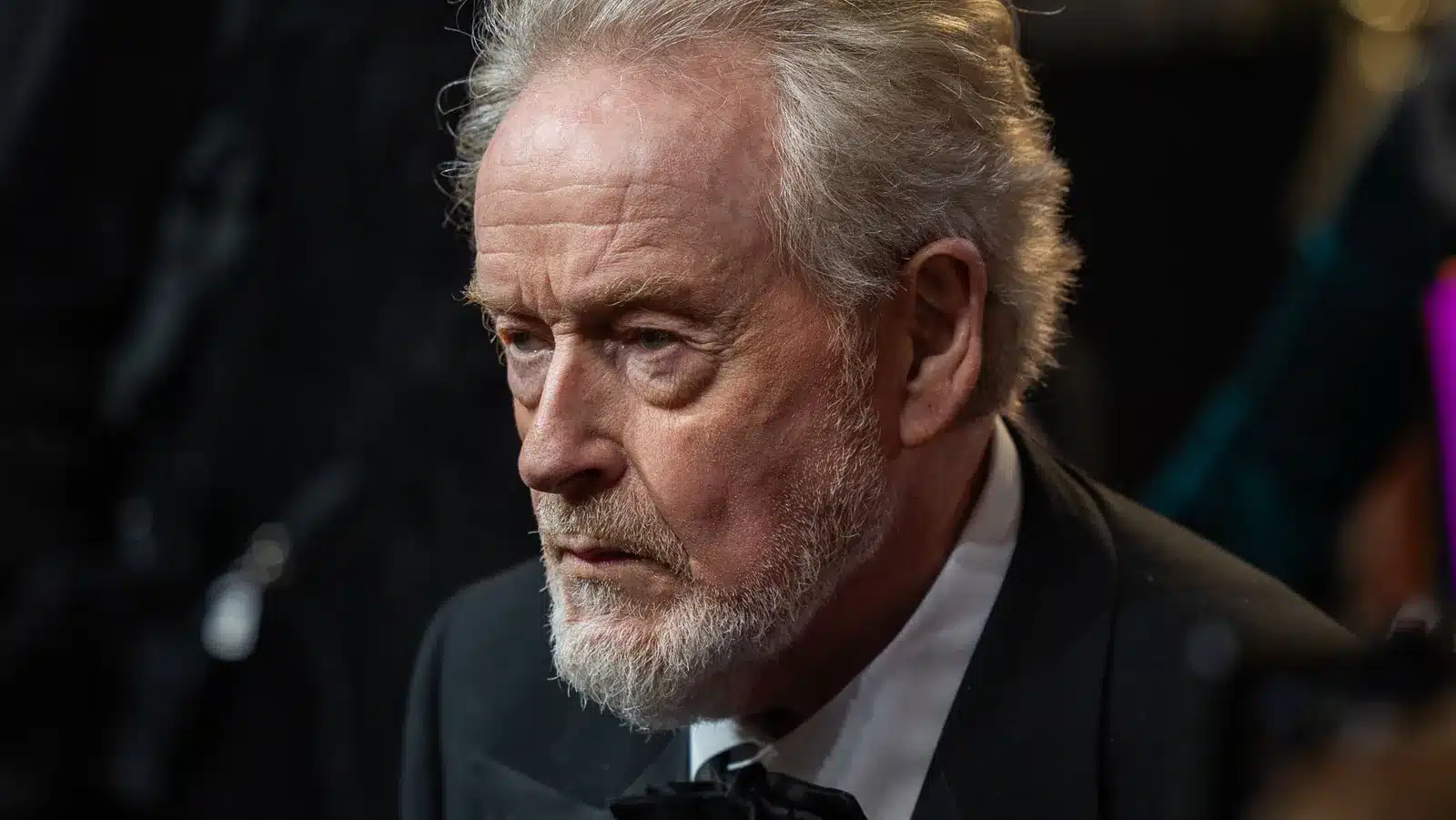

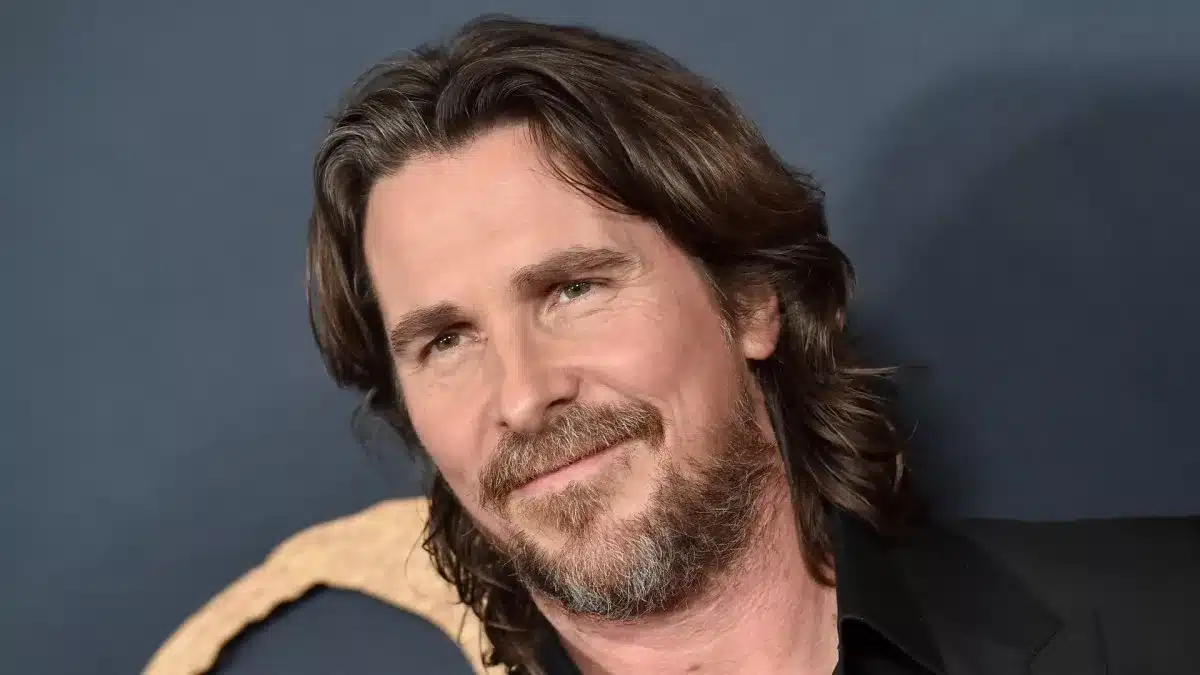

The rest of the cast provides hints of potential. Tim Heidecker is good as Cameron’s agent, Jim Jefferies impresses as Isaiah’s doctor, and Julia Fox is surprising as Isaiah’s wife. These are not enough, however, to offset Wayans’s overacting or make up for the incoherence of the plot. The upshot is a movie that caters to the very hunger for violence and spectacle it professes to decry.

Ultimately, Him can’t choose between being a snappy commentary on the football-industrial complex or a gory sports slasher meant to quench audiences’ gore cravings. It suggests brilliant concepts – the mixing of Christian ethics, nationalism, and football culture – and then serves them up in clunky allegories and impossible situations.

What might have been a biting dissection of America’s love affair with football turns instead into a mess of over-the-top spectacle. As either sports drama or horror, Him fails to get the ball in the end.

Him is currently in U.S. theaters as of 19 September, with Australian releases on 2 October and U.K. releases on 3 October.