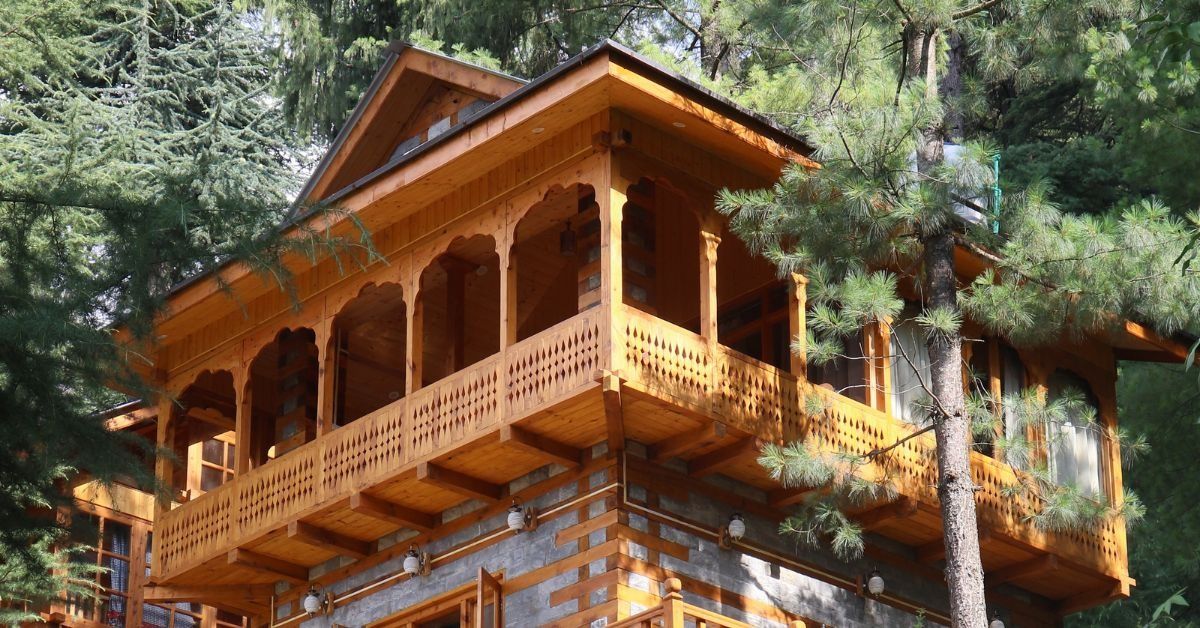

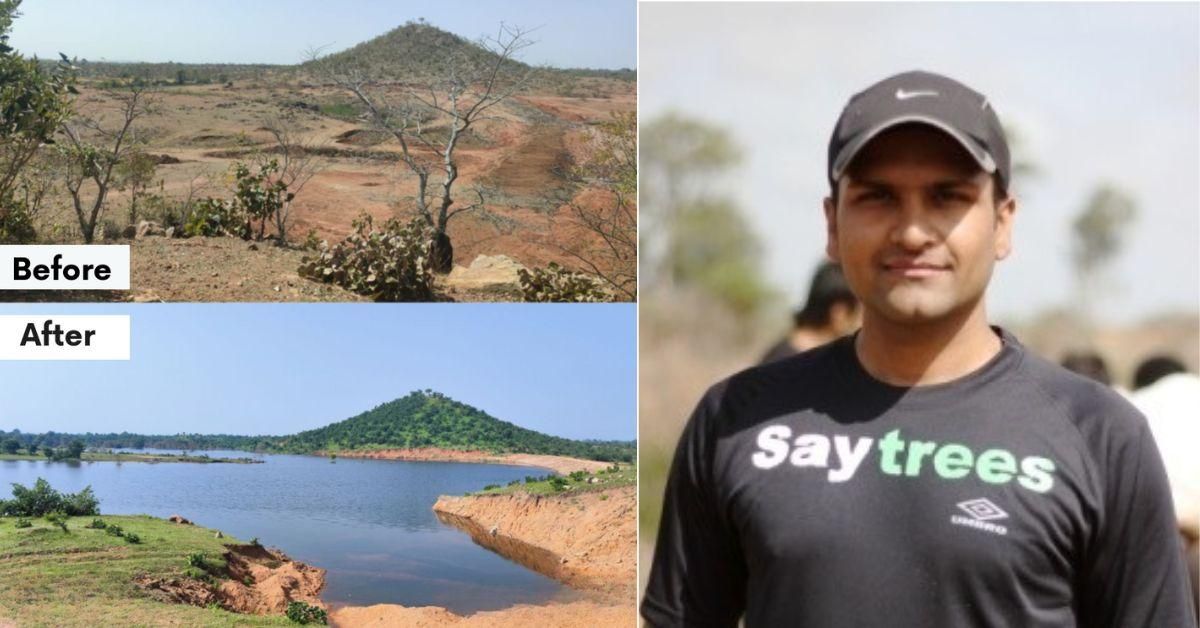

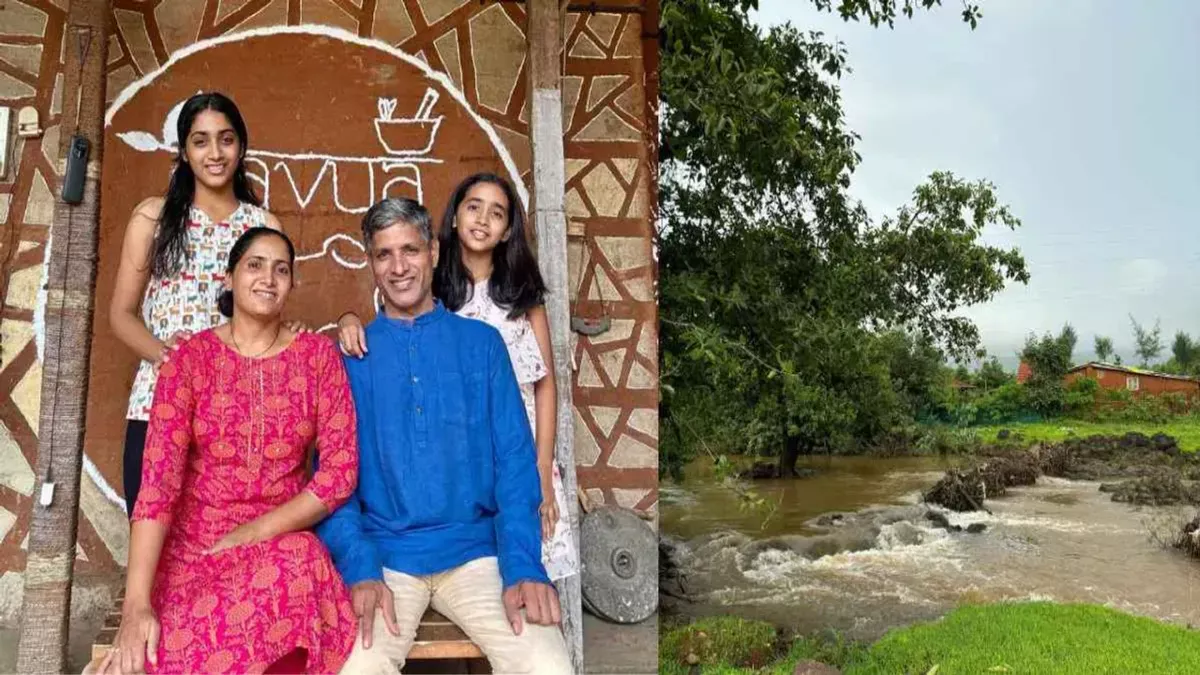

A verdant sprawl greets anyone who reaches Shillim, a village cosied in the breathtaking Sahyadri mountain ranges in Maharashtra.

Would you believe the land is a corollary of a family trip in 1985?

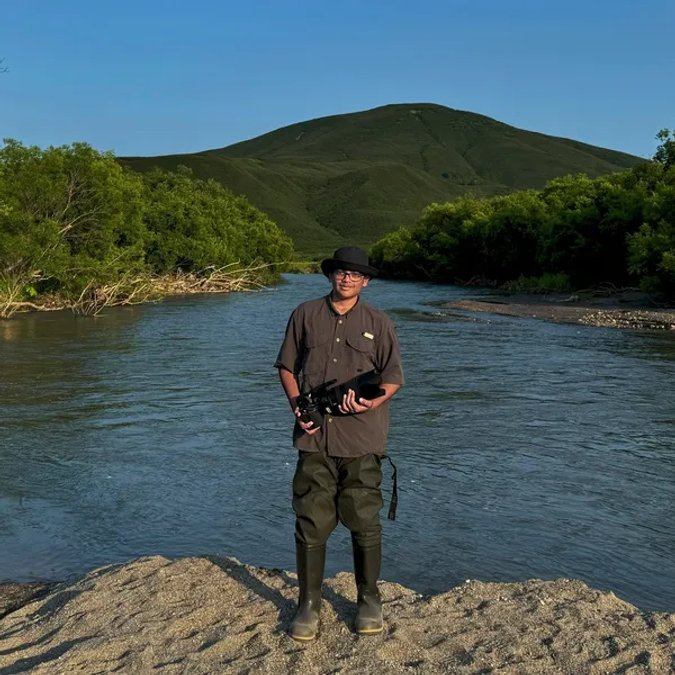

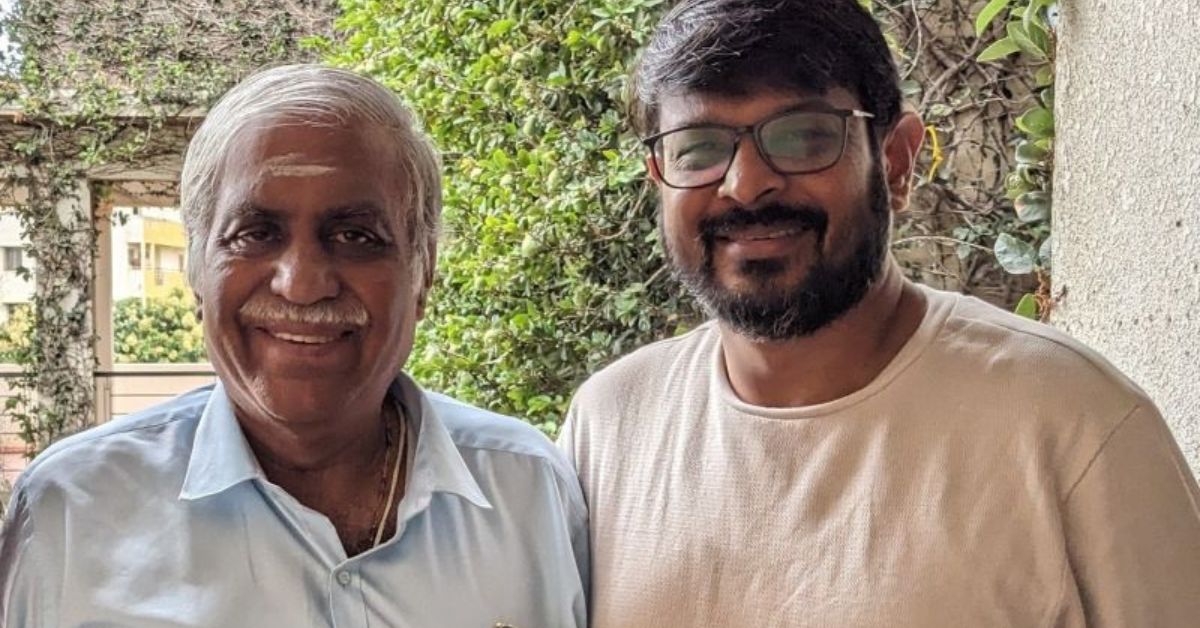

Gavin de Souza, who is now leading Dharana at Shillim — a retreat nestled in the crook of the valley’s arm — tells the story of how his father William and uncle Denzil had bought a home in Khandala that year. The duo spent many an idyllic weekend there; their itineraries stretched to capacity with fruit picking, bird watching, and mountain hikes.

But against the green was an eyesore, a smoke that would continually rise into the air. As the brothers discovered, the haze emanated from paddy being burnt.

The Adivasis(tribal people native to this region) explained to the curious duo that this practice was essential to their traditions. The burning produced ash, which supposedly infused the soil with nutrients, they explained. But the brothers tried to explain that perspective was missing the point. The benefit to the land was only temporary. Once the effects ebbed, the weeds and pests would come back in full force.

But coaxing the tribes out of old habits couldn’t be done overnight. And so, William and Denzil deduced the only sure-shot way of preserving Shillim — “a third of the valley was already scorched, and the entire forest was at risk”, recalls Gavin, from what his father shared with him — was to buy the land.

/filters:format(webp)/english-betterindia/media/media_files/2025/09/15/dharana-at-shillim-2025-09-15-18-55-41.jpg)

Today, the family’s resolve to regreen an erstwhile barren piece of land is visible across 2,500 acres, with more than one million trees standing proud and tall on the Shillim estate.

Dharana at Shillim: Transforming 2,500 acres into a living lab for conservation

One million trees. That’s how many stand proud and tall on the Shillim estate.

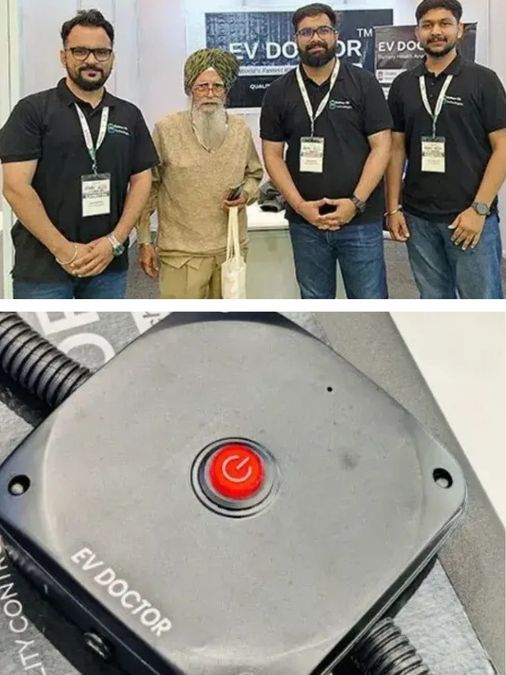

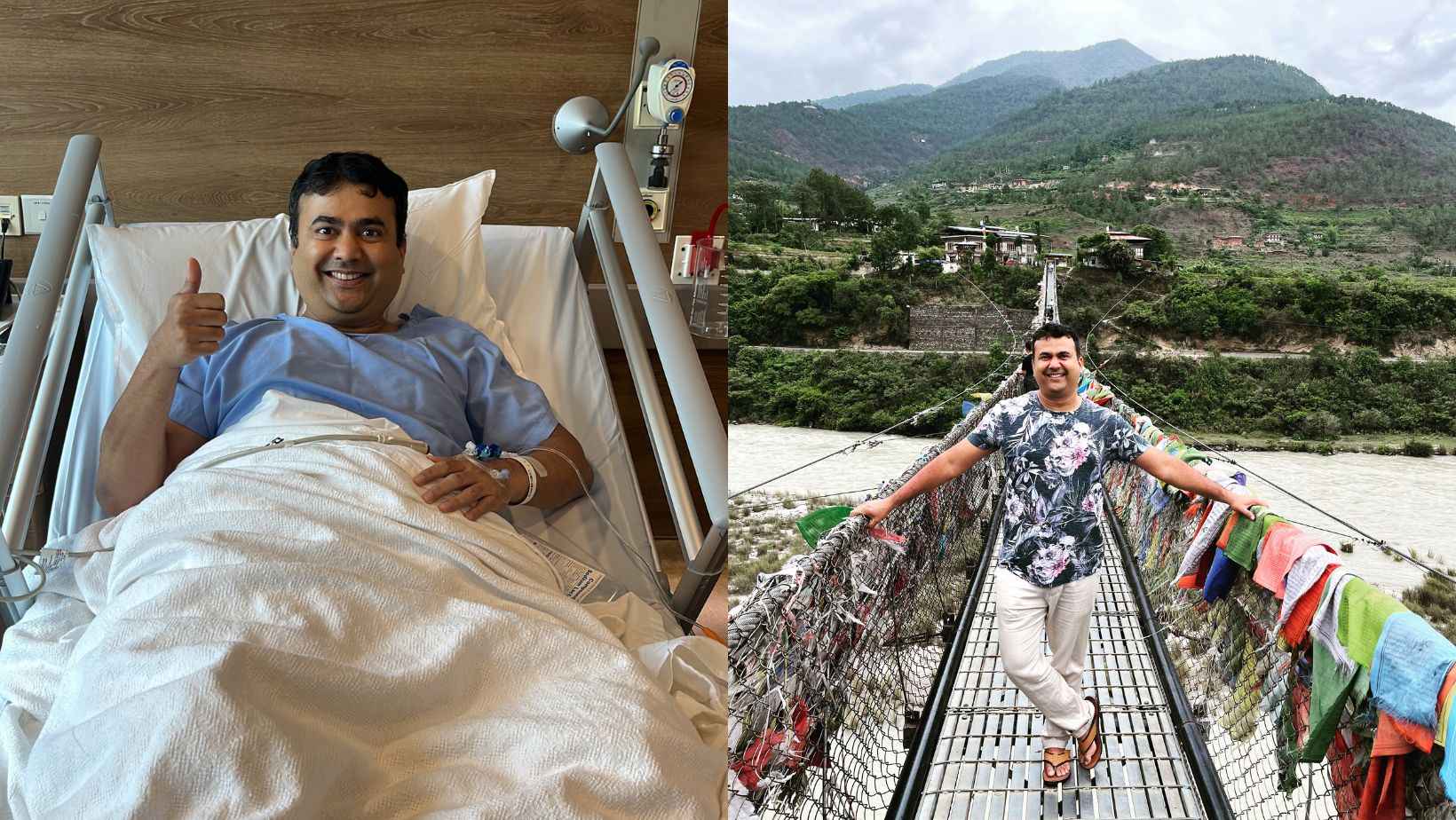

It took 25 years to acquire and conserve the valley and a decade to build the project, Gavin shares, reasoning that their driving force was their deep love for nature. This is reflected in the 100-odd villas that run on energy that is harnessed from the sun.

/filters:format(webp)/english-betterindia/media/media_files/2025/09/15/dharana-at-shillim-4-2025-09-15-19-04-35.jpg)

“Around 70 percent of the estate’s energy needs are fulfilled by solar energy through the 500 megawatt solar plant on the land. All waste is treated through an aerobic technology, while all food waste is turned into compost. This ensures the food goes back into our fields.” Around 50 percent of the produce comes from the fields on the land.

Creating this universe of self-sufficiency was intentional.

/filters:format(webp)/english-betterindia/media/media_files/2025/09/15/dharana-at-shillim-1-2025-09-15-18-59-28.jpg)

Explaining how they have never strayed far from their ecological conscience, Gavin shares, “We’ve never used pesticides on the property; the soil here is pure.” He adds that they have a fleet of EVs (electric vehicles) for the pickups for their guests from both international airport hubs of Mumbai and Pune. But what is now a picture of sustainability, four decades ago, looked quite different.

It was heartbreaking for William and Denzil to watch a pristine parcel of green being destroyed through jhum (slash and burn) cultivation. The ancient technique is not without consequences. It takes its toll on the land’s health. To encourage a positive shift on the land, the family had horticulturist Radha Veach set up a nursery on the backwaters of Pawna Lake. The technique was simple: to collect seeds from the forest and initiate a planting programme hinged on letting native species thrive.

Rewilding a land guided by the rhythms of nature

Picture a forest in its prime. Picture it burnt to the ground, all in a matter of days. The devastating loss of tree cover will take years to recover. The ecology will take decades to be nursed back to health.

But simply pointing out these outmoded sensibilities to the villagers wasn’t enough.

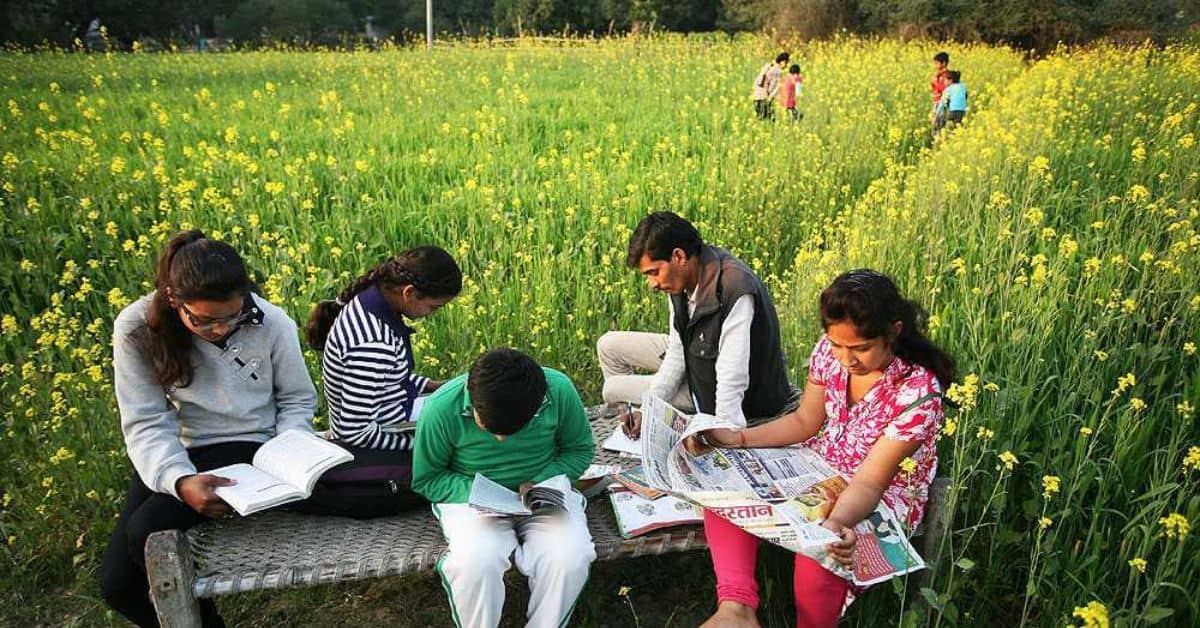

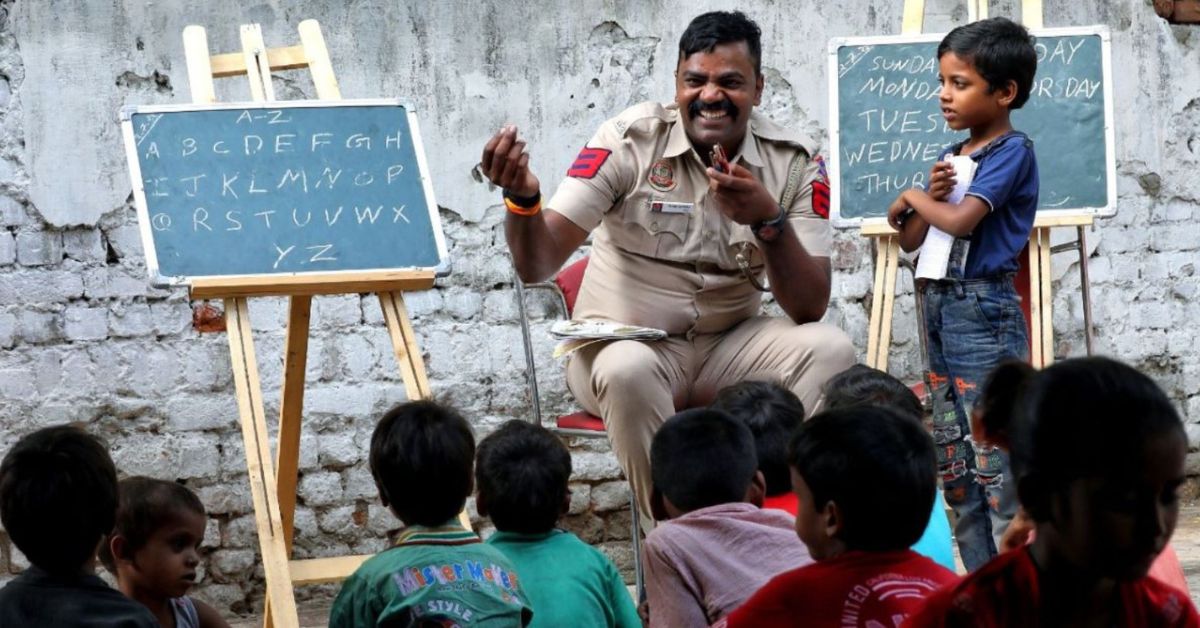

Thus began the journey of turning the locals into custodians of their land. “Village men were engaged to protect the land, prevent forest fires, curb slash-and-burn practices, and stop wildlife hunting, while women managed the nursery and took charge of the annual monsoon planting,” Gavin explains.

/filters:format(webp)/english-betterindia/media/media_files/2025/09/15/dharana-at-shillim-2-2025-09-15-19-00-48.jpg)

/filters:format(webp)/english-betterindia/media/media_files/2025/09/15/dharana-at-shillim-3-2025-09-15-19-02-08.jpg)

Simultaneously,efforts were on to resurrect the forest that had died. “We first had to understand what species of flora existed there back in the day, and then replant a specific species native to that region,” Gavin explains. The family worked closely with the Savitribai Phule Pune University to understand the land’s behaviour through surveys.

One of the first things he learnt was the importance of controlling soil erosion before commencing any growing.

“We started to plant local grasses to create channels for water to go back into Pawna Lake.” Decades of doing this yielded success. A good indicator of a successful rewilding programme, they deduced, is when birds like the hornbills or the endangered Malabar squirrel started to reoccupy the land.

But, Gavin points out, the blueprint for their work in eco-restoration rested on a bedrock of scientific information that came from the Shillim Institute, the “conscience keeper of Shillim” as he describes the NGO, which is headed by his sister Karen de Souza.

Integrating scientific knowledge into eco-restoration

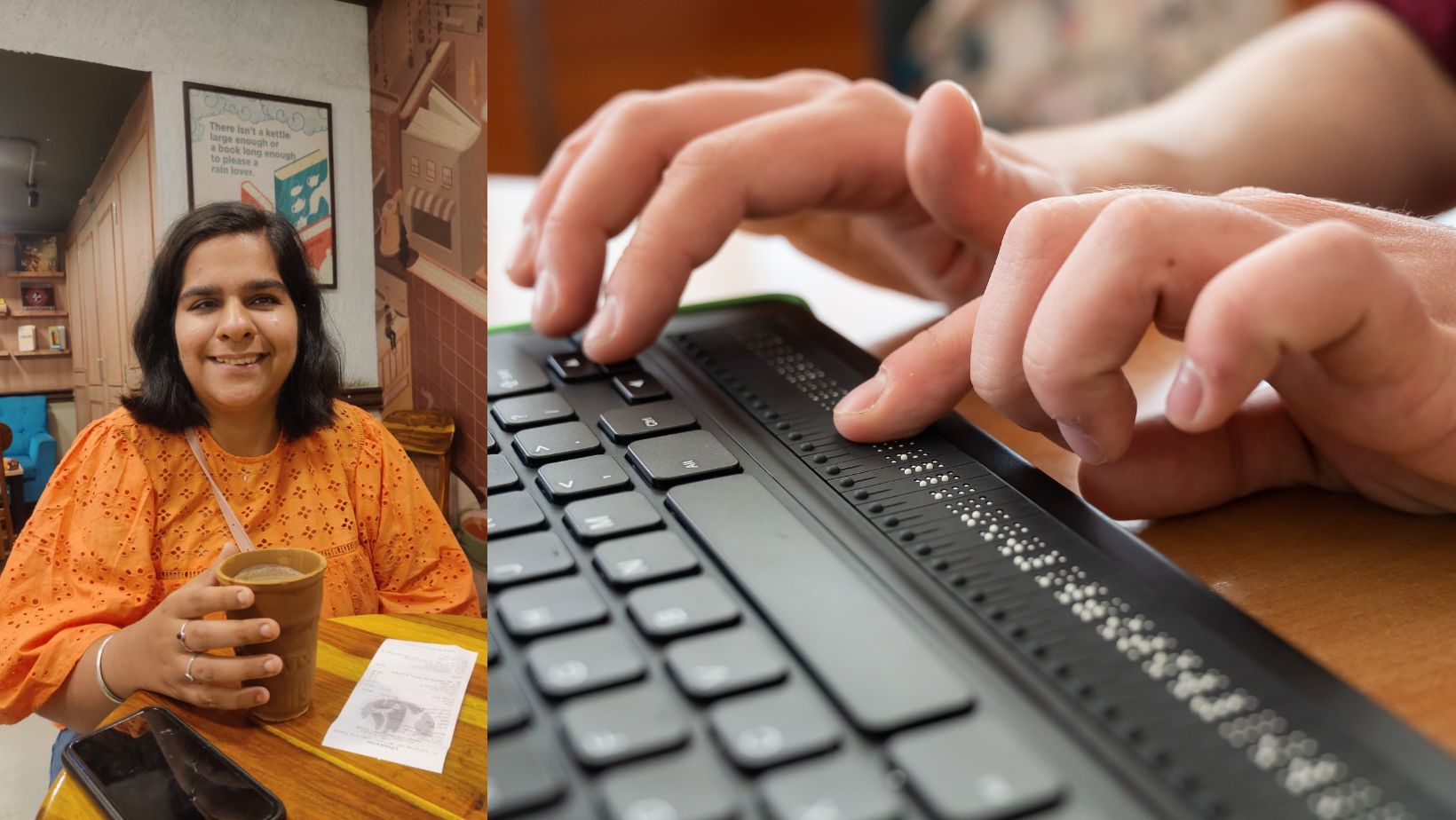

Out of the different types of trees that were native to the land — dense forests, semi-deciduous forests, among others — Karen underscores the importance of the sacred groves, sharing that there are more than 20 of these on the land, sacrosanct among the local communities.

Through the ecological surveys conducted, she points out, the goal was to gauge the habitats that these sacred groves supported with respect to the mammals, birds and reptiles. Aside from eco-restoration, too, Karen shares that the Shillim Institute prides itself on its many programmes that are directed towards having an impact on the locals’ lives.

Take, for instance, the Forest Guard program by way of which training sessions are conducted to teach essential knowledge and skills for prompt and effective responses to snake bite incidents. This kind of training not only bolsters public health measures but also strengthens community safety, while supporting conservation efforts for these vital reptiles, Karen shares.

/filters:format(webp)/english-betterindia/media/media_files/2025/09/15/dharana-at-shillim-5-2025-09-15-19-06-35.jpg)

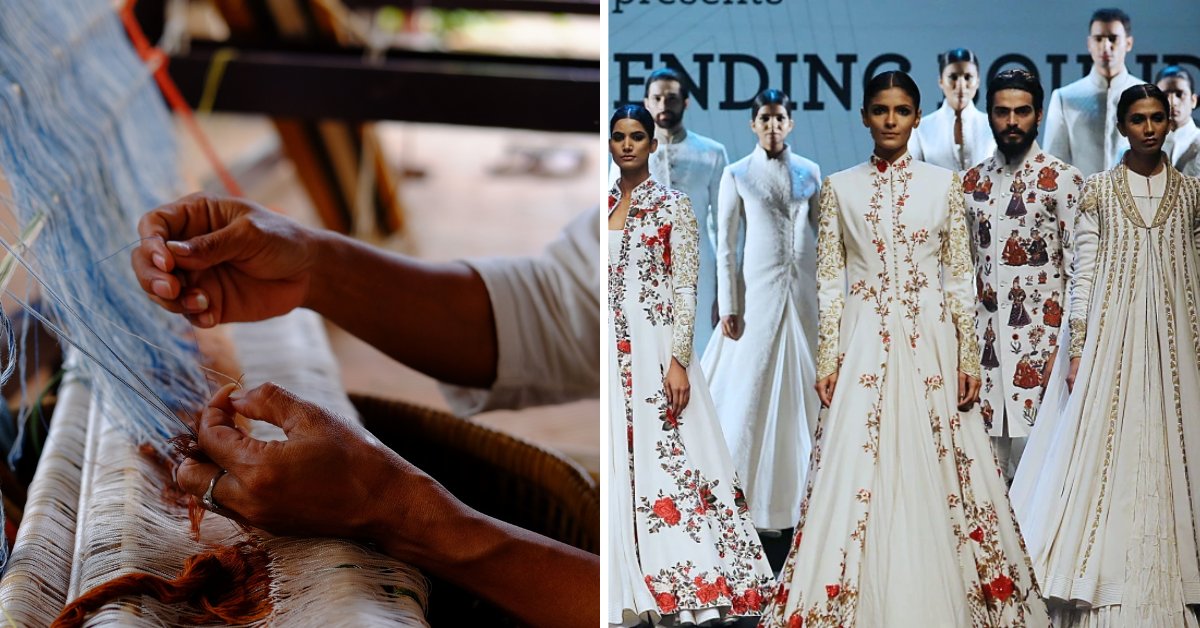

Meanwhile, their rural craft program preserves traditional crafts and engages the local community culturally. The initiative promotes cultural conservation and provides economic opportunities by promoting artisanal skills. They conduct crochet workshops for women from neighbouring communities, offering practical guidance, personalised feedback, and opportunities to experiment with diverse techniques and projects.

Their conservation initiatives include tree plantation drives with native saplings to the construction of watershed structures like gully plugs, stone bunds, and percolation ponds, which encourage the natural growth of grass, and vegetation management practices, including local seed dispersal, hardy tree planting, and invasive species removal, further contribute to the ecosystem’s health.

You’ll be able to see the tangible impact of their work during your stay at Dharana at Shillim. Your stay at the retreat will also offer you numerous chances to detox through the many programmes offered here, such as the Panchakarma programme, which includes a lymphatic cleanse, dietary programmes targeting gut health and immunity-boosting programmes.

But while you let yourself relax, maybe find time now and then, for a stroll through the green acres. Let the forest serve as a reminder to shed old habits and embrace new ways of living. This time with nature.

Edited by Vidya Gowri Venkatesh, All pictures courtesy Dharana at Shillim