Growing up in Kolkata in the 1970s, caste was not a big part of my life. You knew it existed of course, from the bride wanted ads and occasional distasteful references to somebody being chhoto jaat (lower caste) as an explanation for their ‘misbehaviour’. But mostly, we lived in the comfortable world of Banerjees and Mukherjees, Ghoshes and Boses, Sens and Sahas, barely aware of the differences in caste.

Caste was unavoidable in JNU. Starting with a classmate who introduced himself and added, brahman, with an ‘r’ creeping into the final ‘n’. He added, like you. I didn’t have the heart to tell him that I was a mere half-caste, a product of a proscribed union.

Caste was everywhere: from very abstruse discussions of the role of caste in Marxist analysis (not clear) to whether there were actually hostel mafias that enforced caste segregation (also not clear), we talked about it all the time.

That is when I started to wonder why things were different in Kolkata, and it occurred to me that in my entire school and college cohorts, there was no one whose family name was identifiably from the scheduled castes. It was almost surely not true — there were probably a small number but I didn’t know them — which didn’t make me feel any better. It started to dawn on me that in Bengal, the lower castes are particularly invisible relative to other parts of India. Much later, I found an emphatic recognition of this point in Monoranjan Byapari’s searing ‘Interrogating my Chandal Life’, based on the author’s extraordinary life experience. A penniless refugee from East Pakistan and member of one of the lowest castes, he made himself into a writer while making a living as a rickshaw puller.

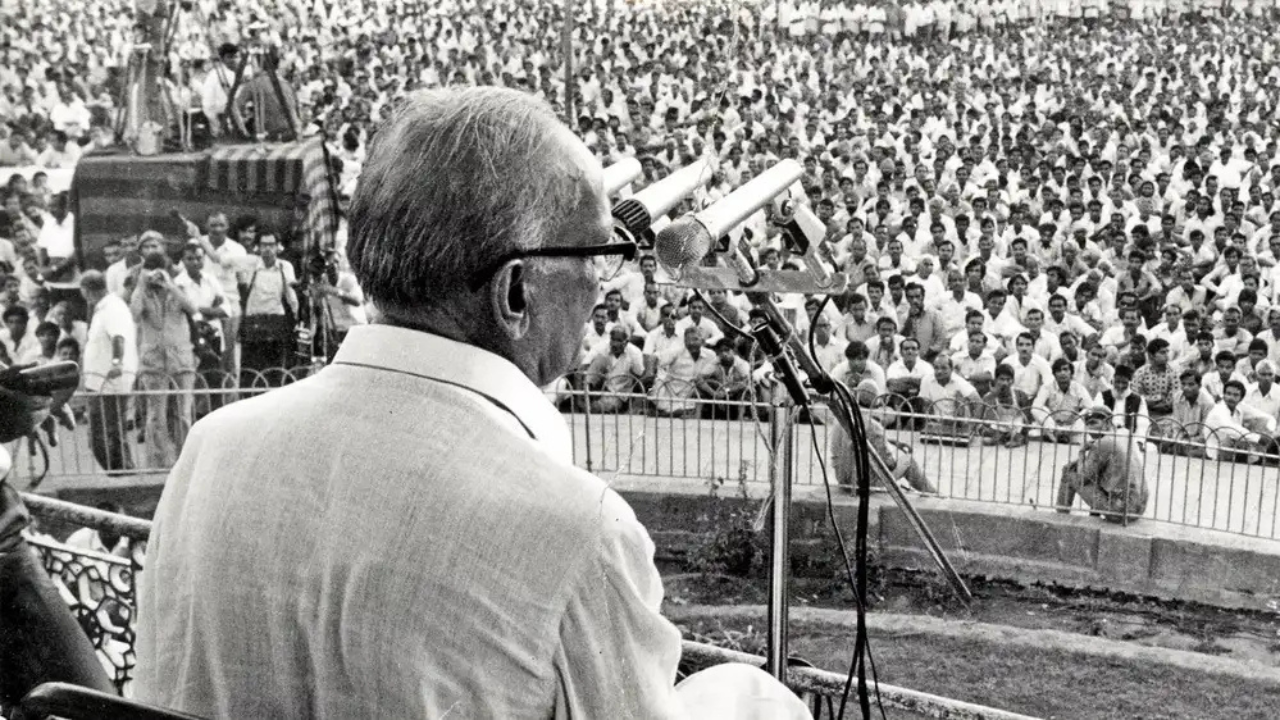

This is not because they are not numerous: Bengal has the second highest share of the overall scheduled caste population, after UP and before Bihar. Yet, unlike in UP, where Mayawati was several times the chief minister, and Bihar, where Jitan Ram Majhi had a brief tenure as CM as well, I am unable to name a leading Bengali politician from Byapari’s world. This includes the Communists, where prominent leaders carried names like Jyoti Basu, Promod Dasgupta, Buddhadev Bhattacharya, Biman Bose, Asim Chatterjee and Kanu Sanyal, all identifiably from the elite castes.

Indeed, before the 2011 publication of ‘Interrogating my Chandal Life’, even someone relatively well-read (like me) would have been hard-pressed to name a major literary piece in Bangla by someone outside the usual elite castes, with the one exception of the justly celebrated ‘Titash Ekti Nodir Naam’ (A River called Titash) by Advaita Mallabarman. By contrast, there is an enormous body of Dalit literature in Marathi that seems to be widely known and read.

Growing up, when we complained about the food, my mother would often fall back upon the fact that in their family, they were expected to eat what the cook produced, which often turned out to be pithla (see recipe below) and bhakri with some palé bhaji (spinach fried with onions) on the side. I knew this was peasant food, and now I find the recipes in Shahu Patole’s fascinating ‘Dalit Kitchens of Marathwada’. My mother’s family was rich by our standards, with a big house and a giant American car. The equivalent family in Bengal might have cooked some Dalit food once in a while as part of a culinary adventure (shutki machher ambal, a sweet-sour chutney made from dried fish), but their day-to-day diet always aspired to something more elaborate and ‘refined’.

This is clearly partly the result of the permanent settlement and the resulting concentration of money and power in a zamindar class, mostly also upper caste for historical reasons. The fact that it was mostly rental income that didn’t need to be earned meant that they had plenty of time to ‘refine’ their cultural moves, thinking up 50-course menus (panchasbyanjan) for family celebrations, putting distance between the Bengali elite and the rest. In Maharashtra, by contrast, much of the land was peasant-held, with no overlords (other than the colonial state).

However, this doesn’t explain why Bengal is politically so different from Bihar and UP, which were also mostly zamindar-dominated. My hunch, and it is no more than that, is that it has something to do with the fact that the Bengali elite castes — the brahmins, the kayasthas, the vaidyas and the vaishyas — mostly got along with each other, at least since the beginning of the 19th century. There were other conflicts, for example, between conservative and liberal Hindus, but not along caste lines. This is unlike in UP and Bihar, where intra-upper-caste cleavages are well-documented. Indeed, Mayawati’s successful 2007 campaign explicitly united the lowest castes with the highest, the brahmins, against the rest. Perhaps this need to find allies in a multi-cornered fight has the limited advantage of bringing some visibility to people who would not otherwise have it, and the absence of overt caste conflict in Bengal creates a false sense of unity, where there is only exclusion.

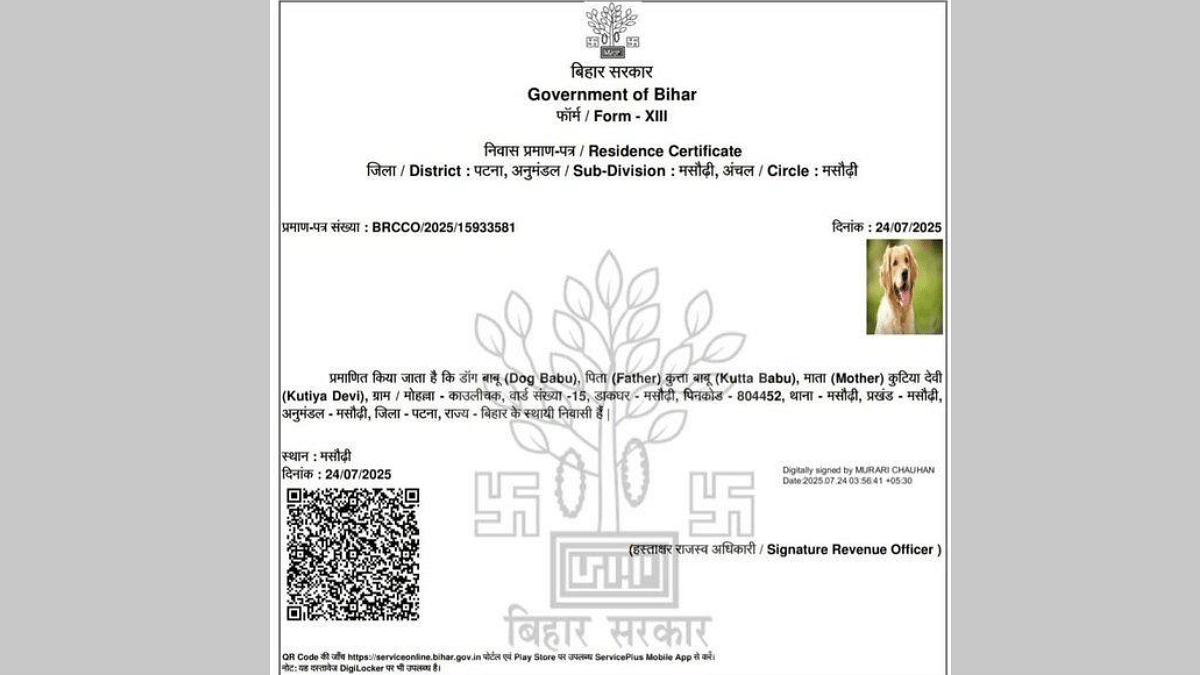

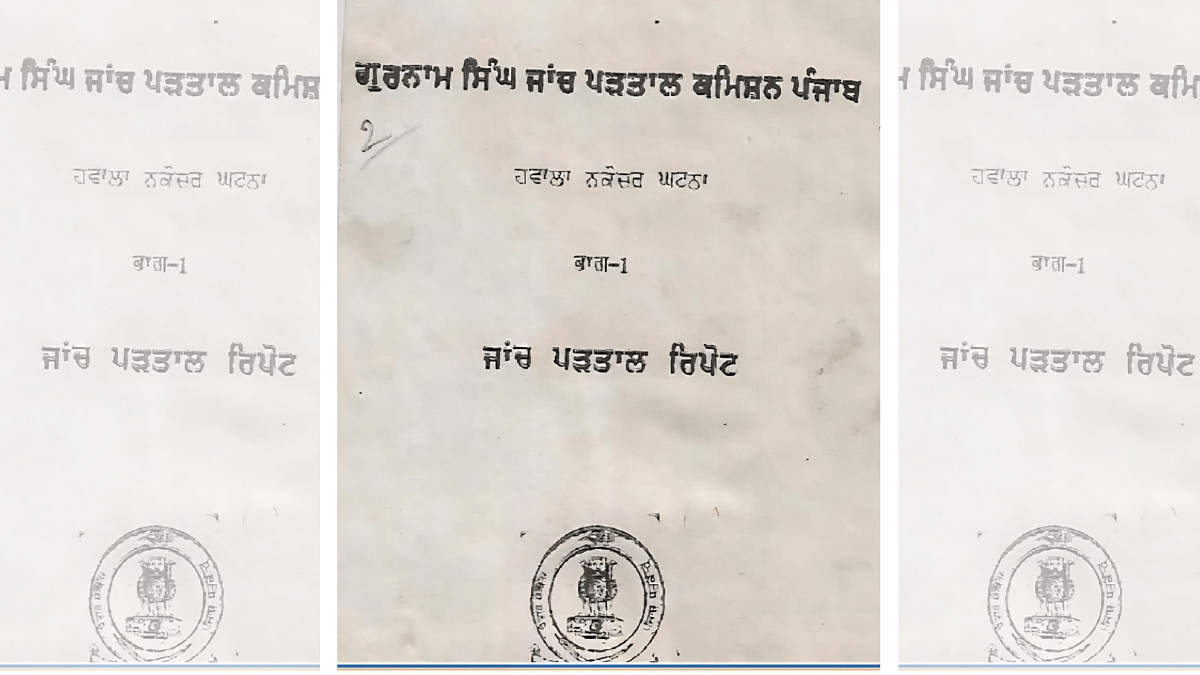

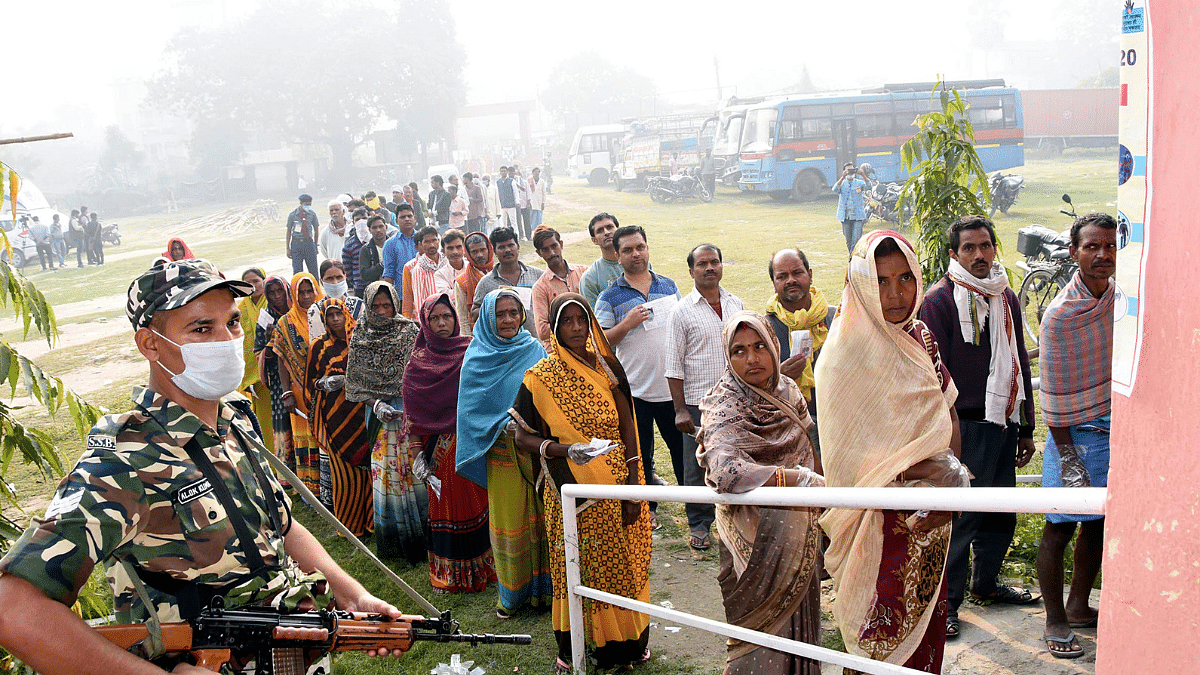

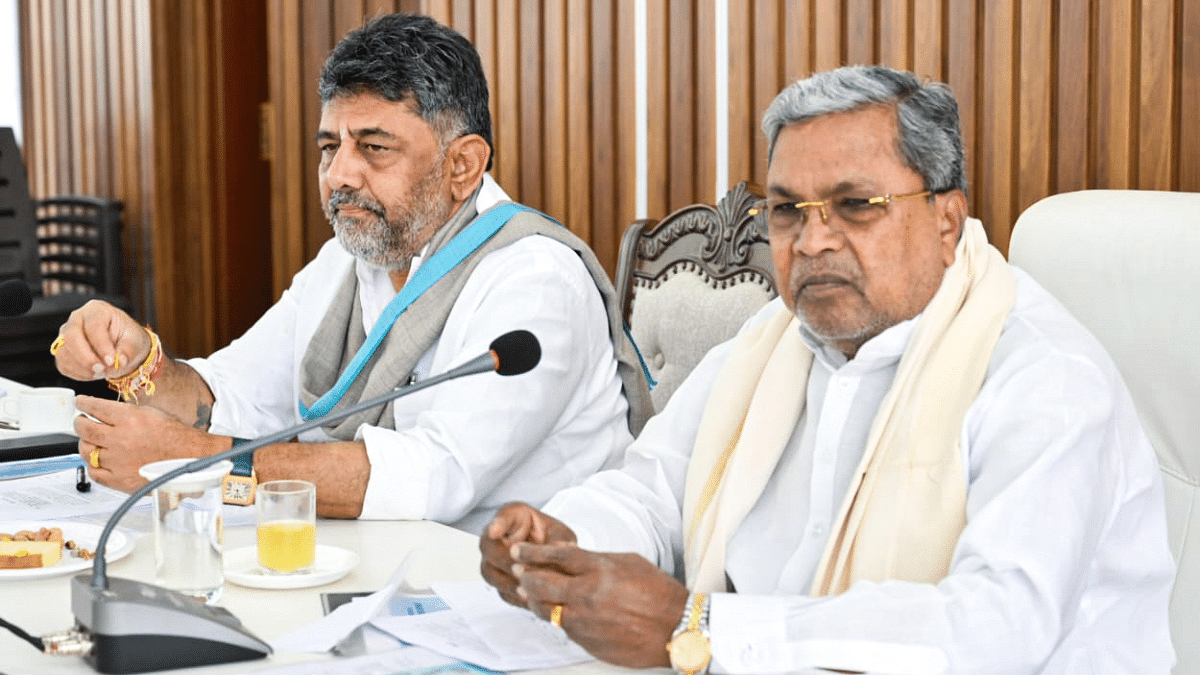

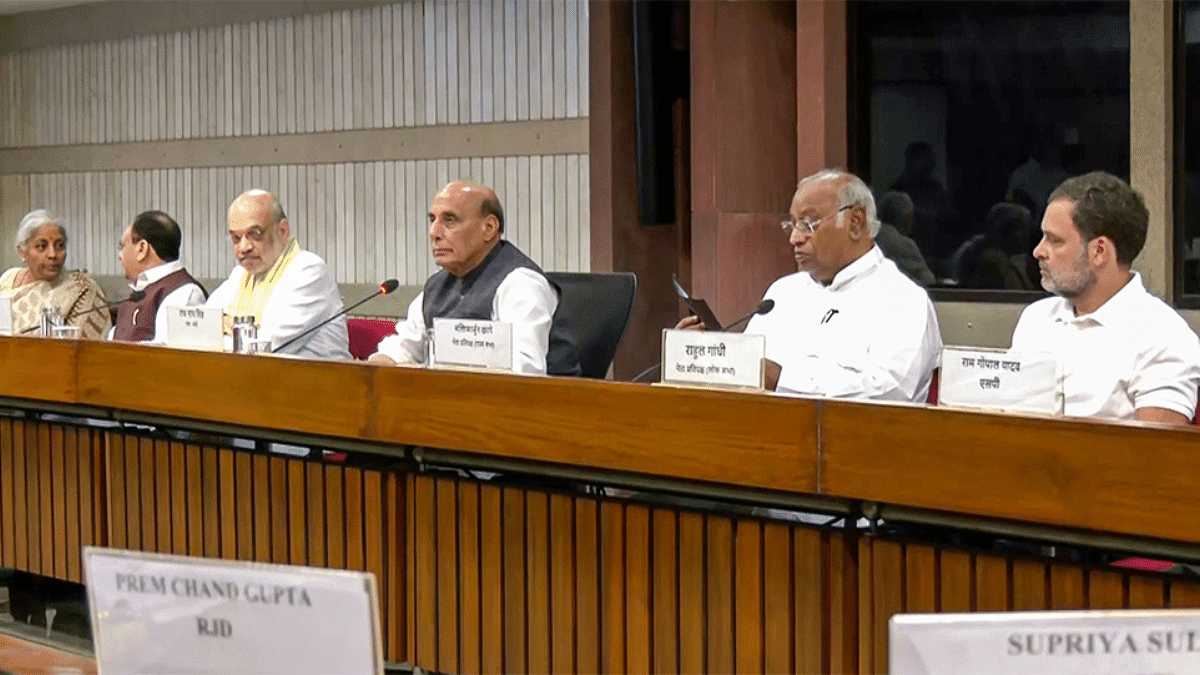

The demand for a caste census, which is now accepted by all major parties, is in part a reaction to this kind of invisibility. Thanks to the Karnataka version of it, we now know that in that state, there is a vast gap in the education levels of Brahmins, Bunts, and Christians on one side and the rest, including the prosperous Vokkaligas and Lingayats. This is handy, especially when dealing with a member of the Indian elite assuring me, usually based on anecdotes, that caste differences are a thing of the past. However, regrettably, these educational gaps get very little weight in the way the press reacts to the various caste censuses (Bihar, Karnataka, Telangana). Those revolve around the population shares of different caste groups as a way to ask whether those groups are getting their appropriate quota of government jobs. Given just how few people have even a moderate chance at these jobs, this might seem like an odd obsession, especially given the scale of unfairness and violence represented by caste.

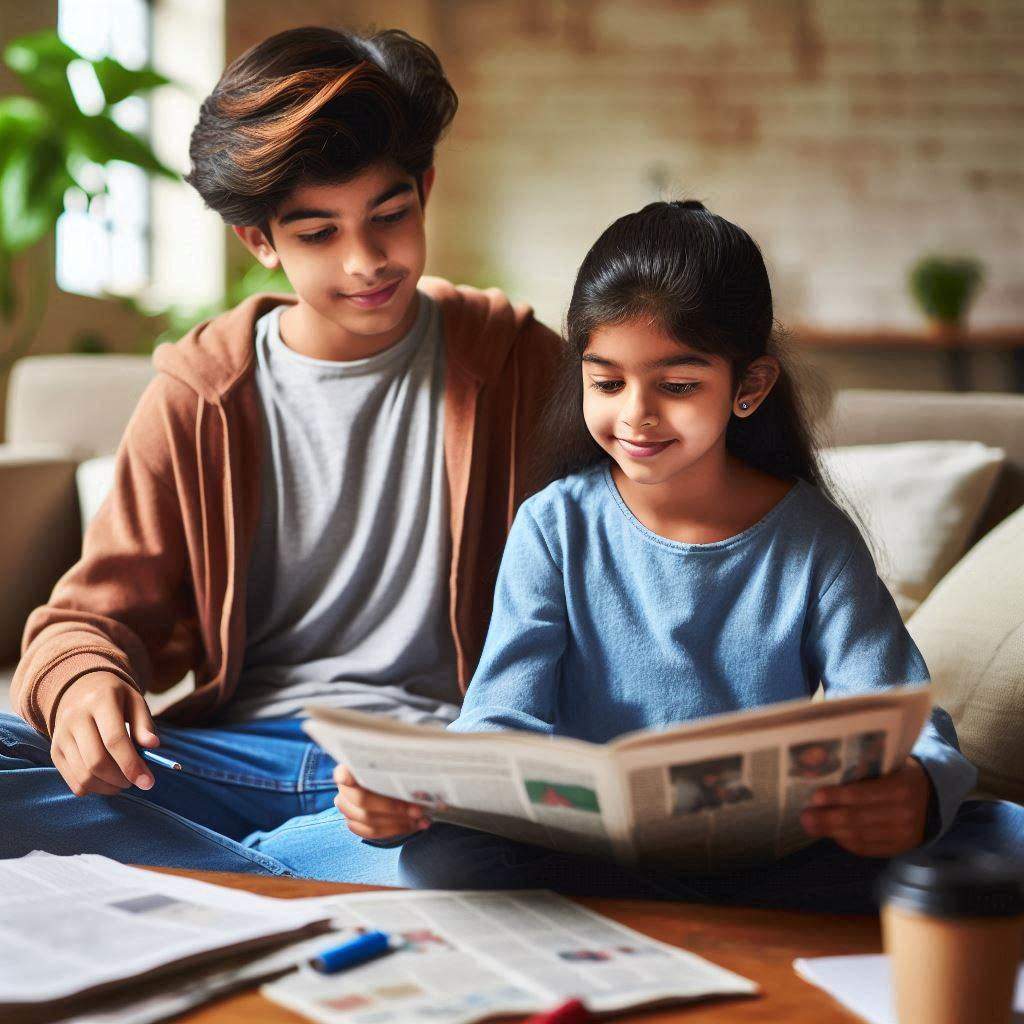

While there is a reasonable case for the quotas themselves as a tool for mobility in a sclerotic society, the fact that they play such a central role in the policy response to caste discrimination seems unfortunate. The zero-sum nature of quotas and the emphasis on competitive exams to get those jobs must contribute to resentment and anxiety rather than building solidarity across groups. A paper in the American Economic Review from nearly two decades ago by Karla Hoff and Priyanka Pandey, provides a vivid example. Karla and Priyanka got 300+ kids across a number of UP villages to solve mazes for prize money. The authors placed some children in groups that combined low and high castes and others that had only one caste. For some of the mixed groups, chosen at random, they got every child to say their whole name, including their caste identifier. In others, it was anonymous. It turned out that this made a huge difference — the lower caste kids solved 20% less mazes than the upper caste kids once they were reminded of their caste differences, but not when they were all anonymous. On the other hand, in all low-caste groups, being reminded of their caste did not affect the performance of the children. In other words, even though there was no actual competition, just the idea of (implicitly) competing with their ‘social betters’ paralysed lower-caste children. Moreover, high-caste children performed the best when they were in the mixed group and they knew they were competing with lower castes. The need to affirm their ‘superiority’ made them try harder.

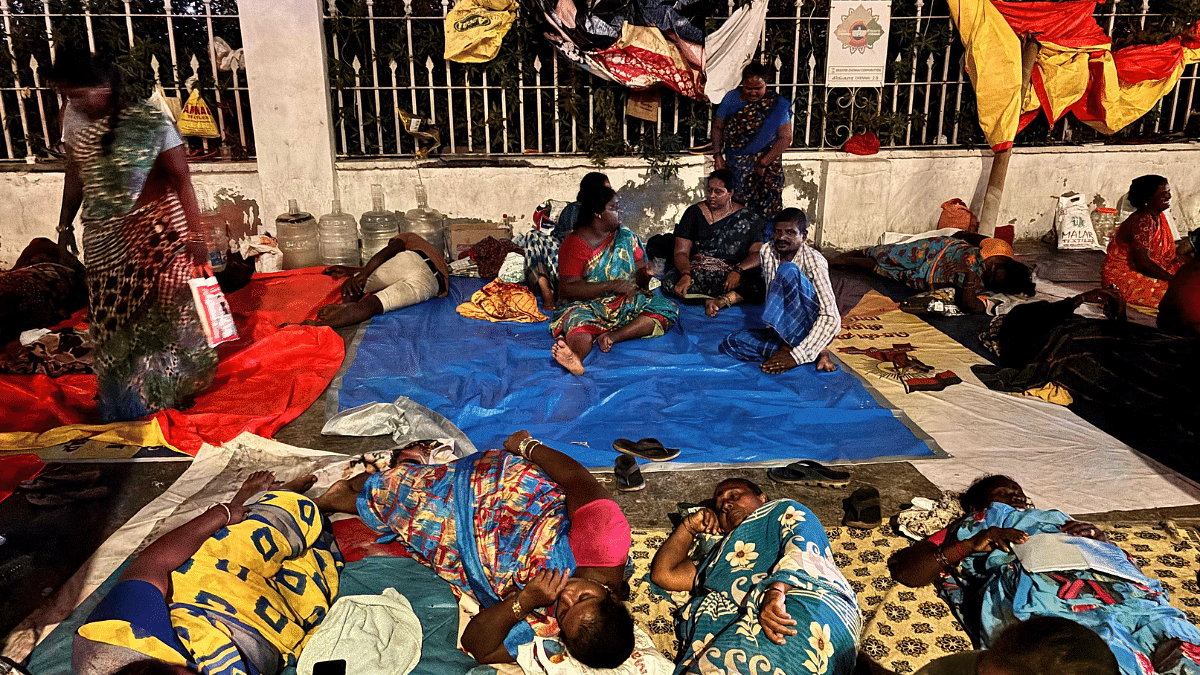

If the ultimate goal is a society where all castes see each other as brothers, then this emphasis on competition for jobs seems inappropriate. On the other hand, I am not able to think of many large-scale social policies in India that try to build bonds across the castes. The nearest thing might be the school meals, which are now more or less universal in government primary schools. When they were introduced, there was a great to-do about whether the upper castes would allow their children to share meals with the rest, especially if the cook was also from the wrong caste. They might even, it was suggested, take their children out of school, better illiterate than impure. While the available data is patchy (or worse), whatever assessment I have seen, by Jean Dreze and others, suggests that, despite occasional flare-ups, this has mostly got sorted. Who they eat with seems less of an issue for the kids today than the quality of the food (ghoogri again? no eggs?). And as I know from years of complaining about the food at MIT to my colleagues, this can be a powerful bonding experience.

This is part of a monthly column by Nobel-winning economist.

Disclaimer

Views expressed above are the author’s own.

END OF ARTICLE