The recent US inflation report was hailed with celebrations, but not all are assured the economy is on solid ground.

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics said that the Producer Price Index (PPI) dropped 0.1% in August, but year-over-year growth remained at 2.6%. Prices for final demand services were down 0.2%, and final demand goods were up 0.1%. The news forced the S&P 500 to all-time highs and motivated the Federal Reserve to slash interest rates by 25 basis points on Sept. 17.

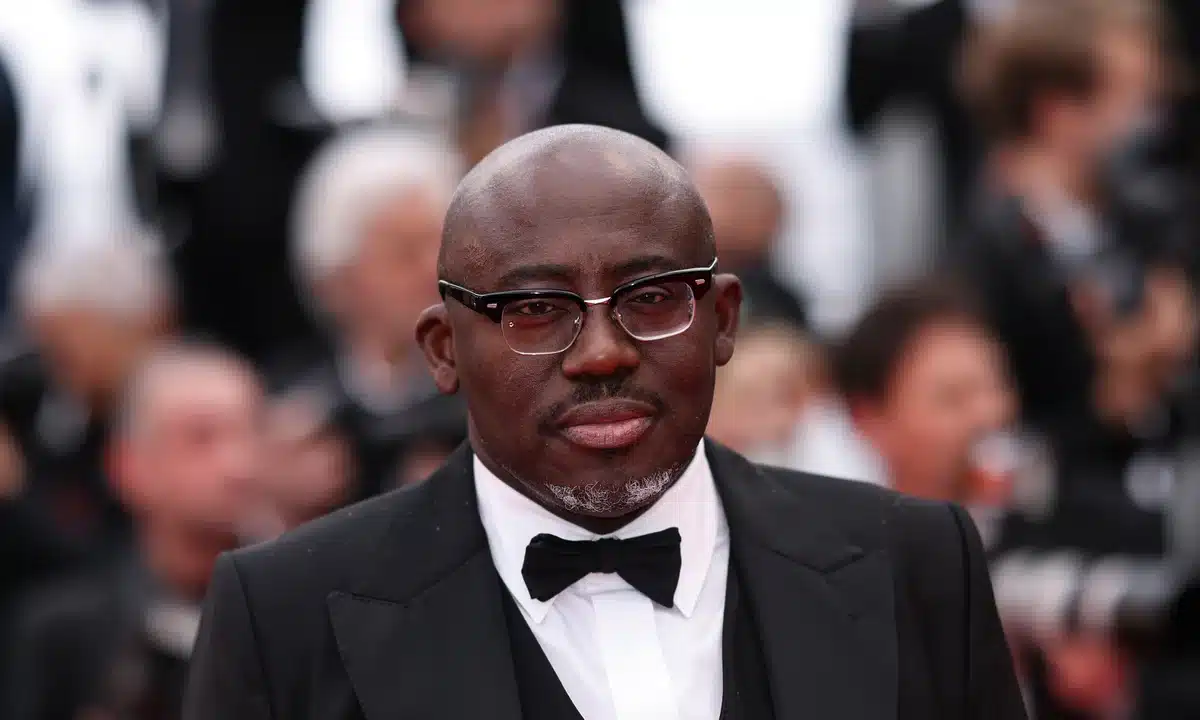

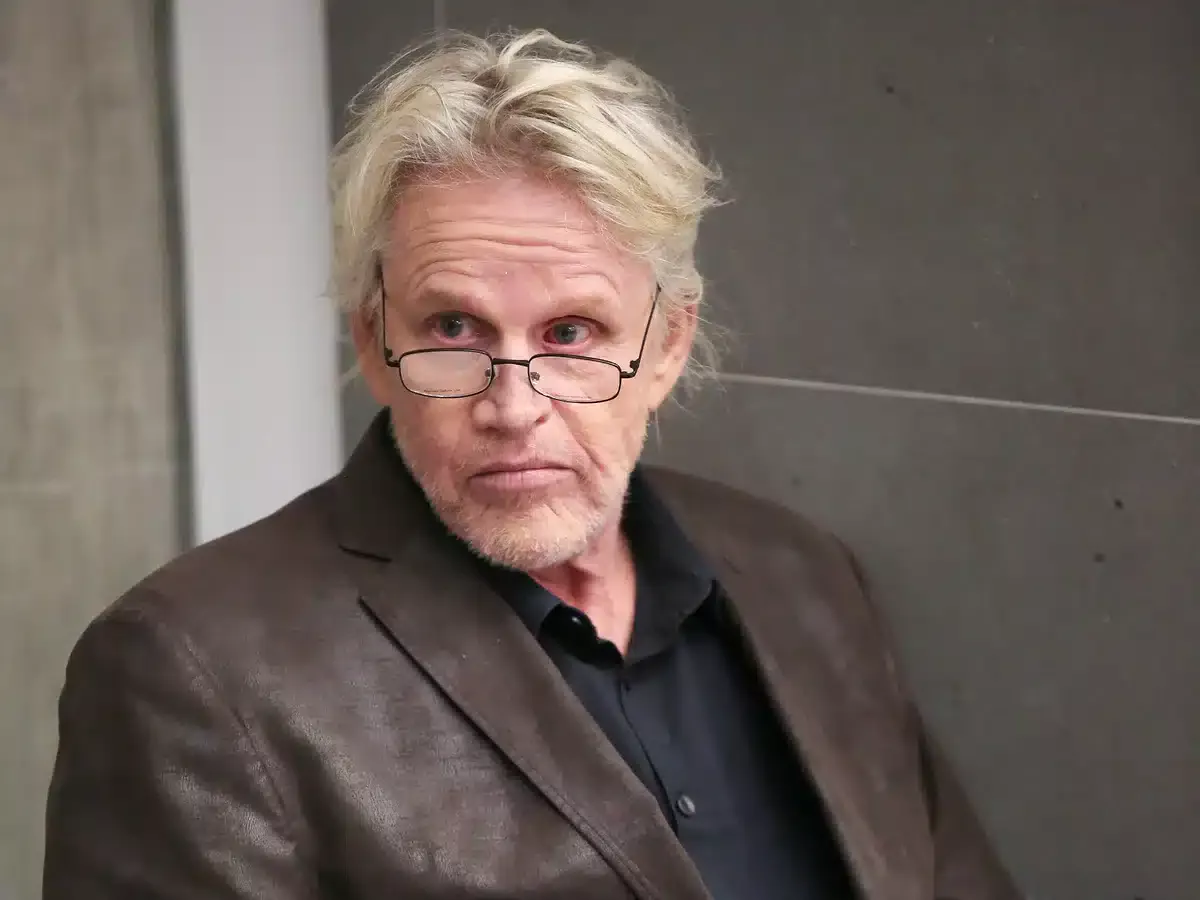

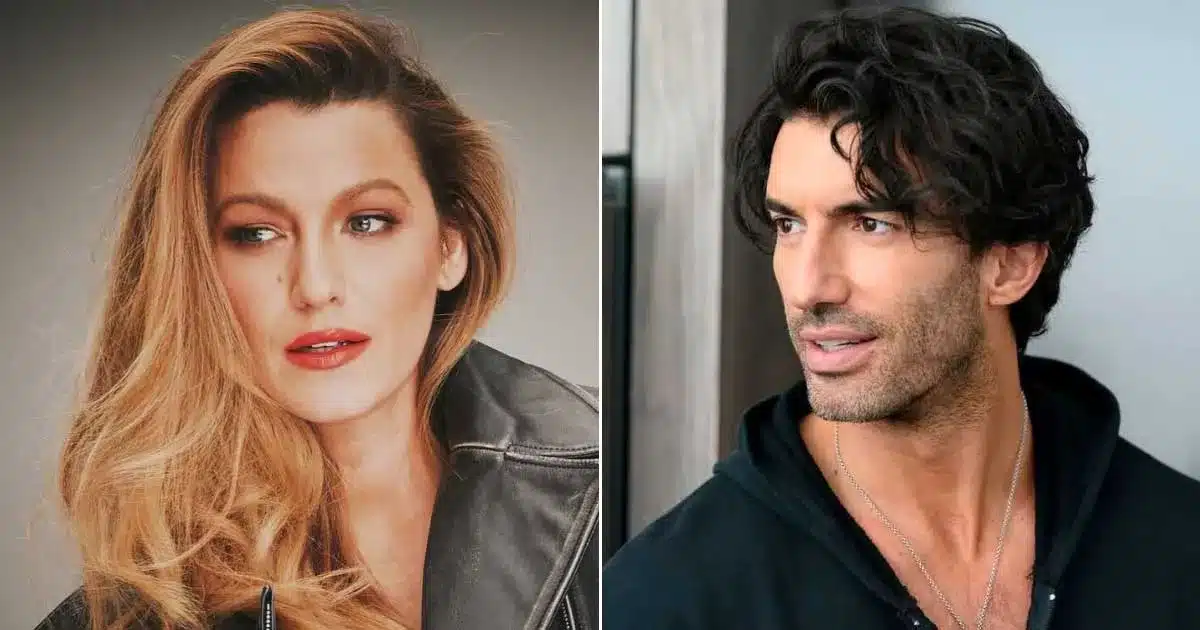

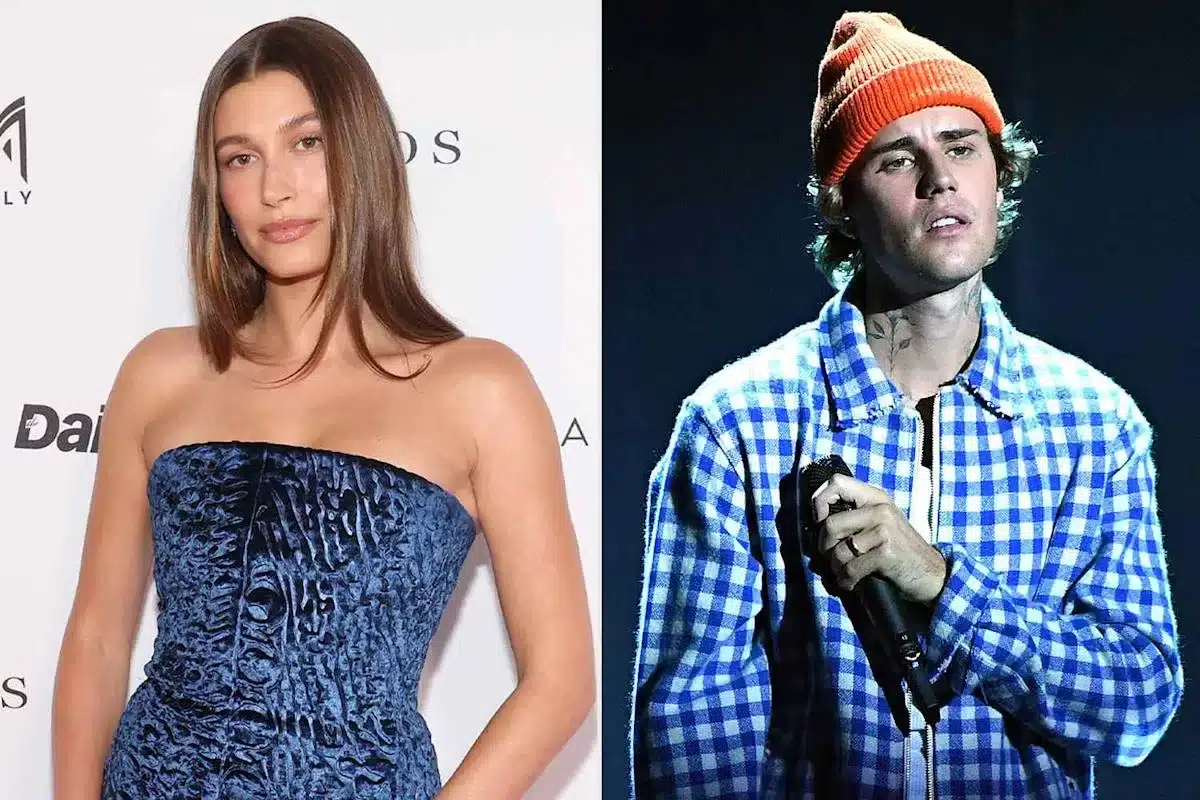

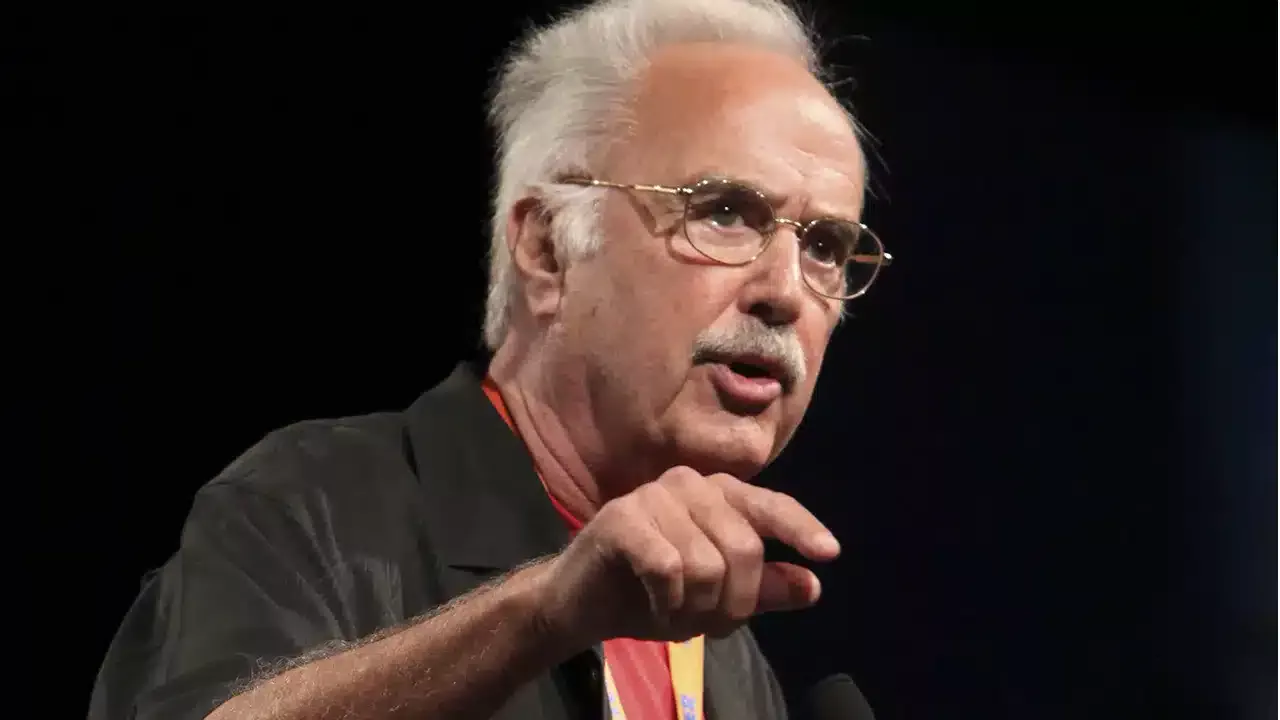

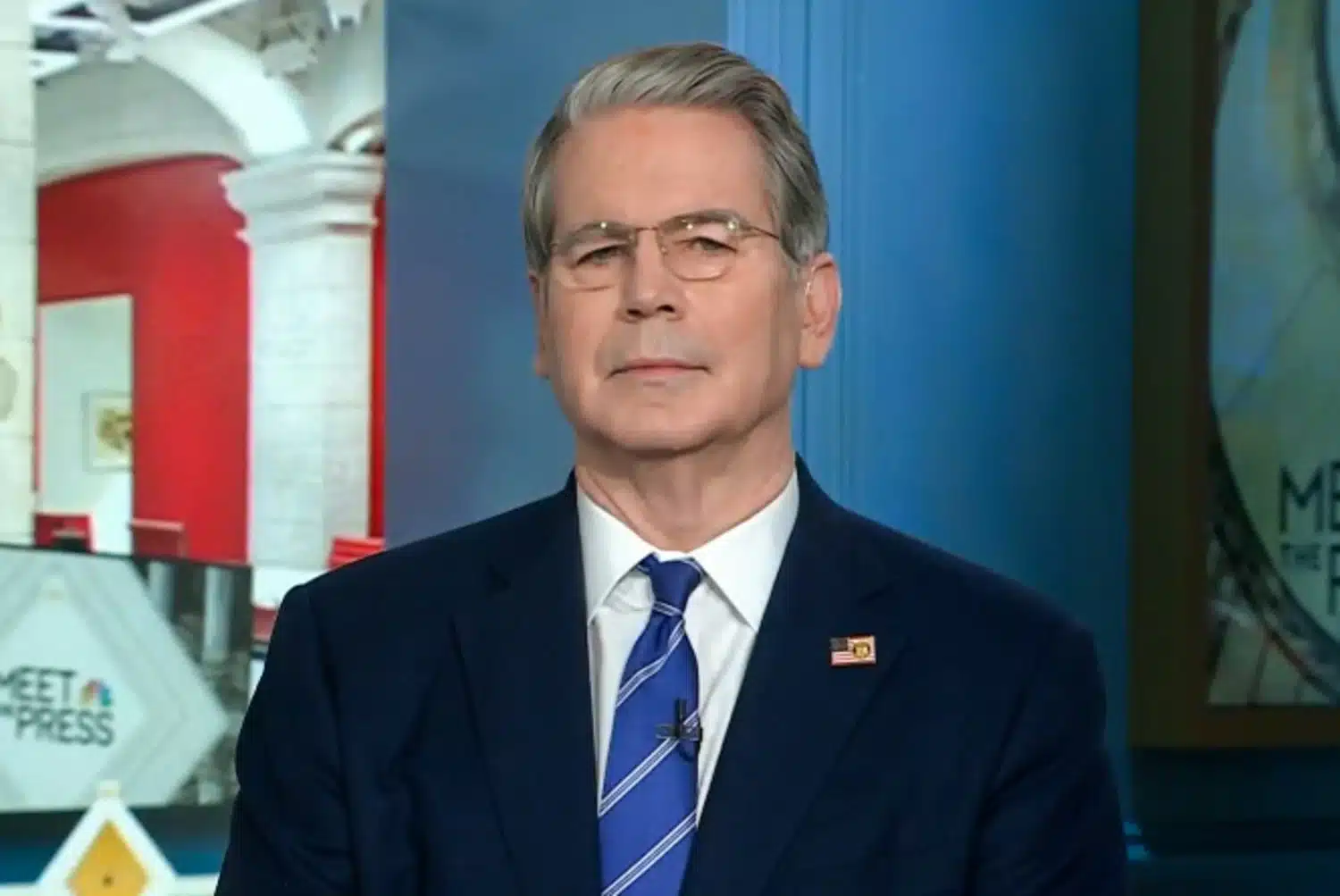

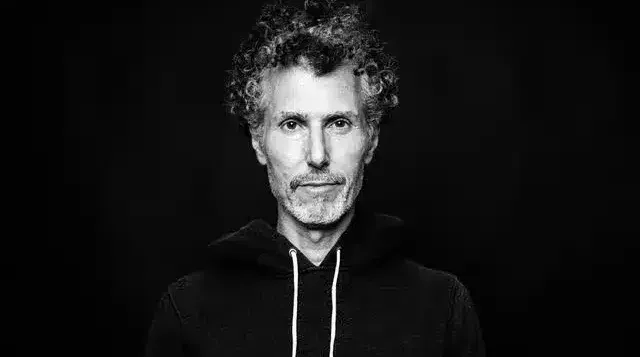

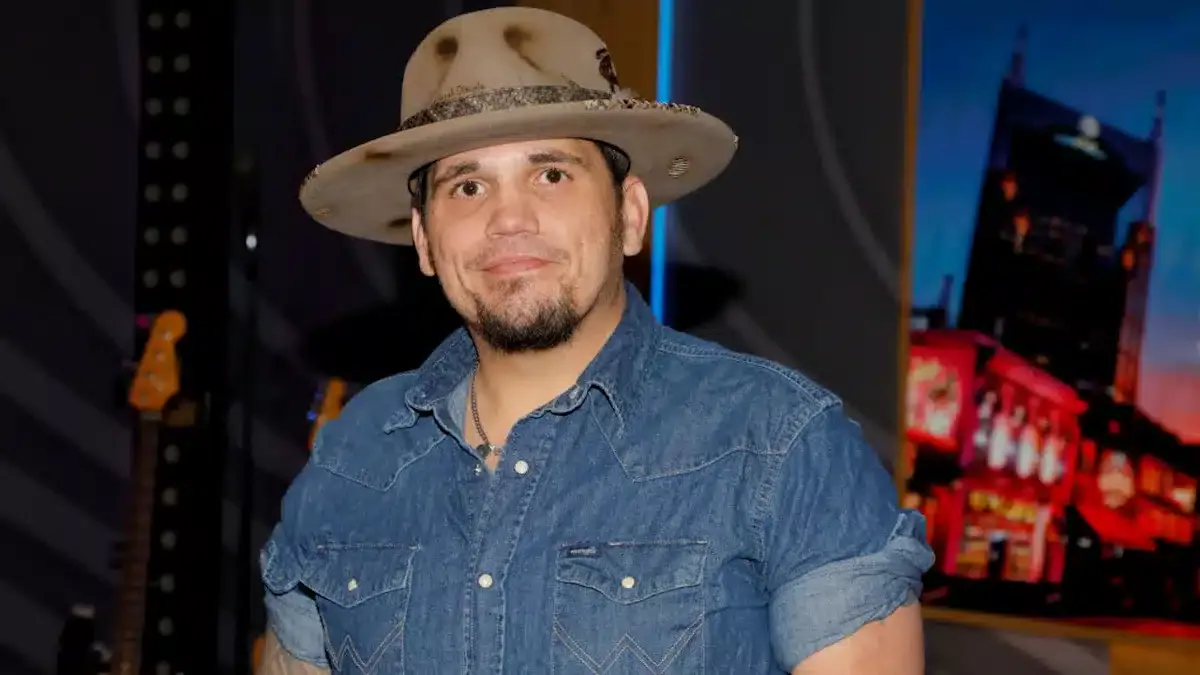

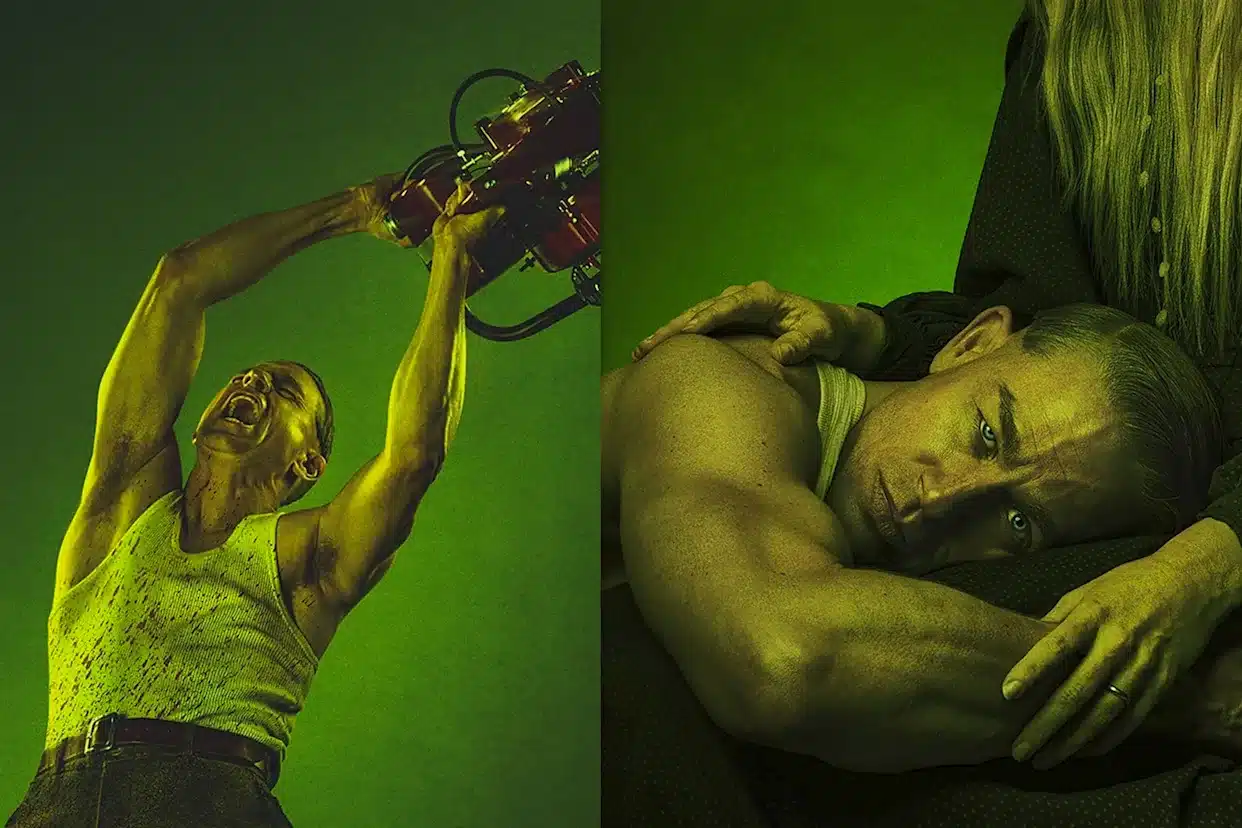

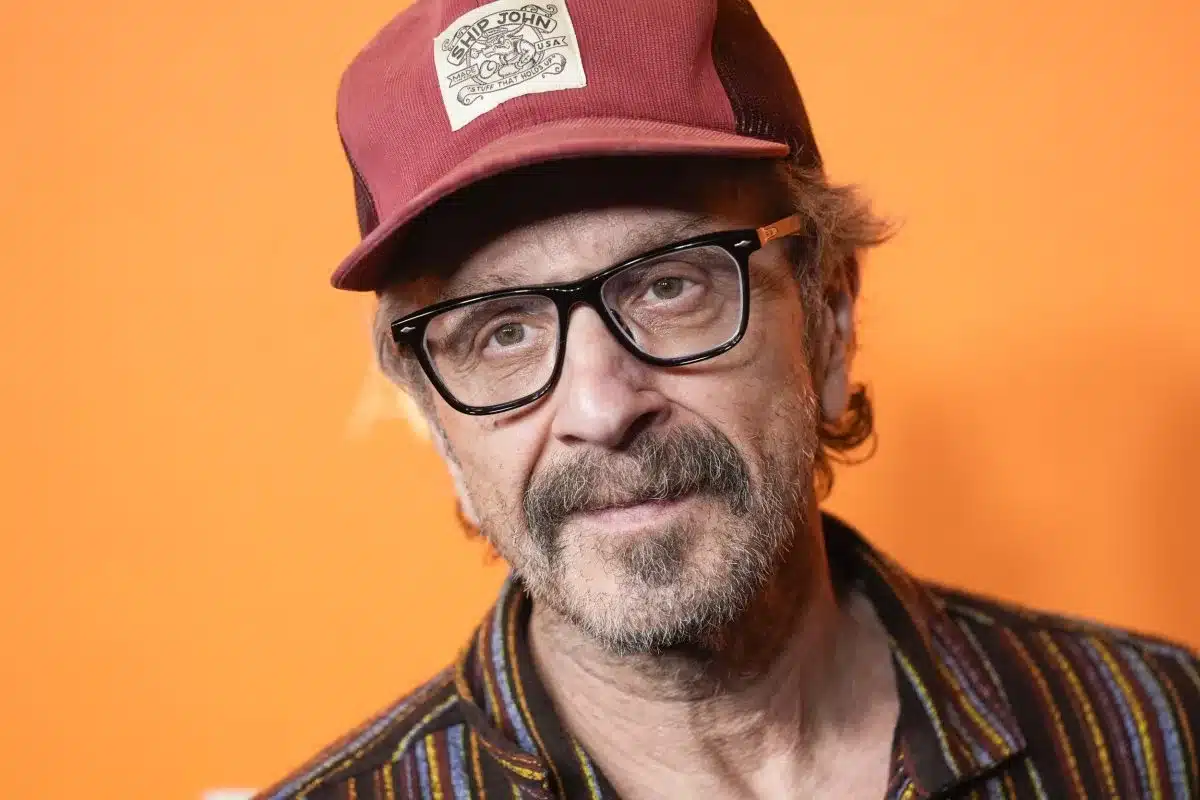

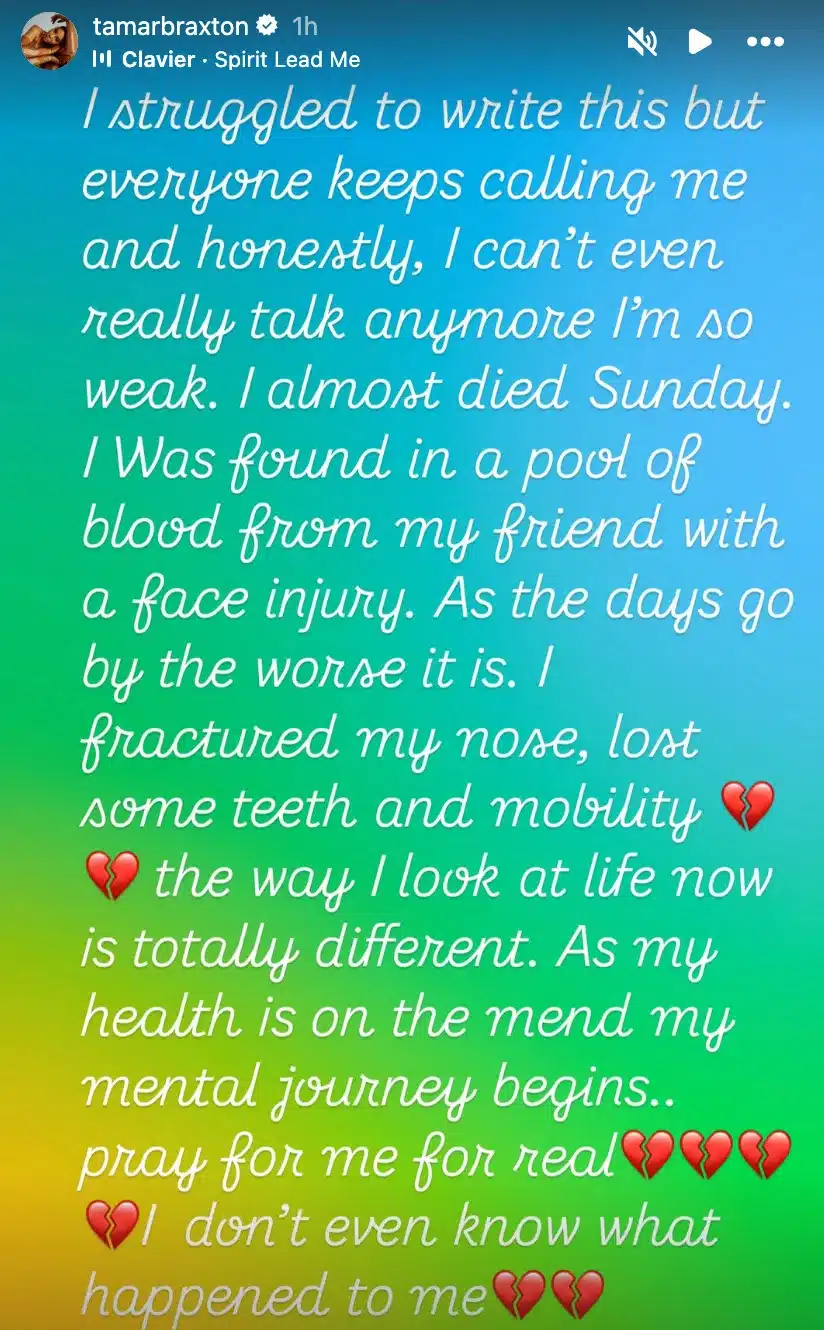

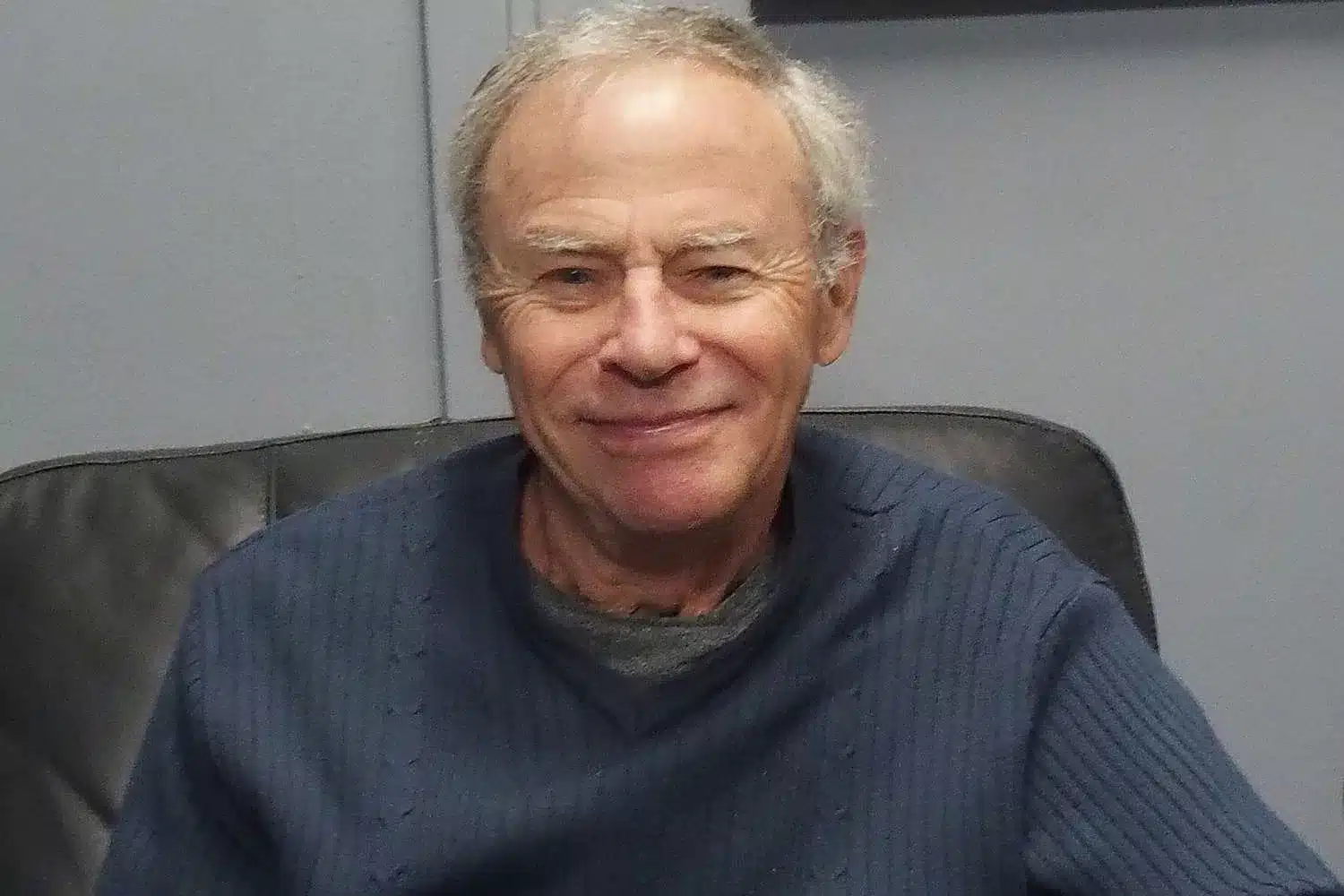

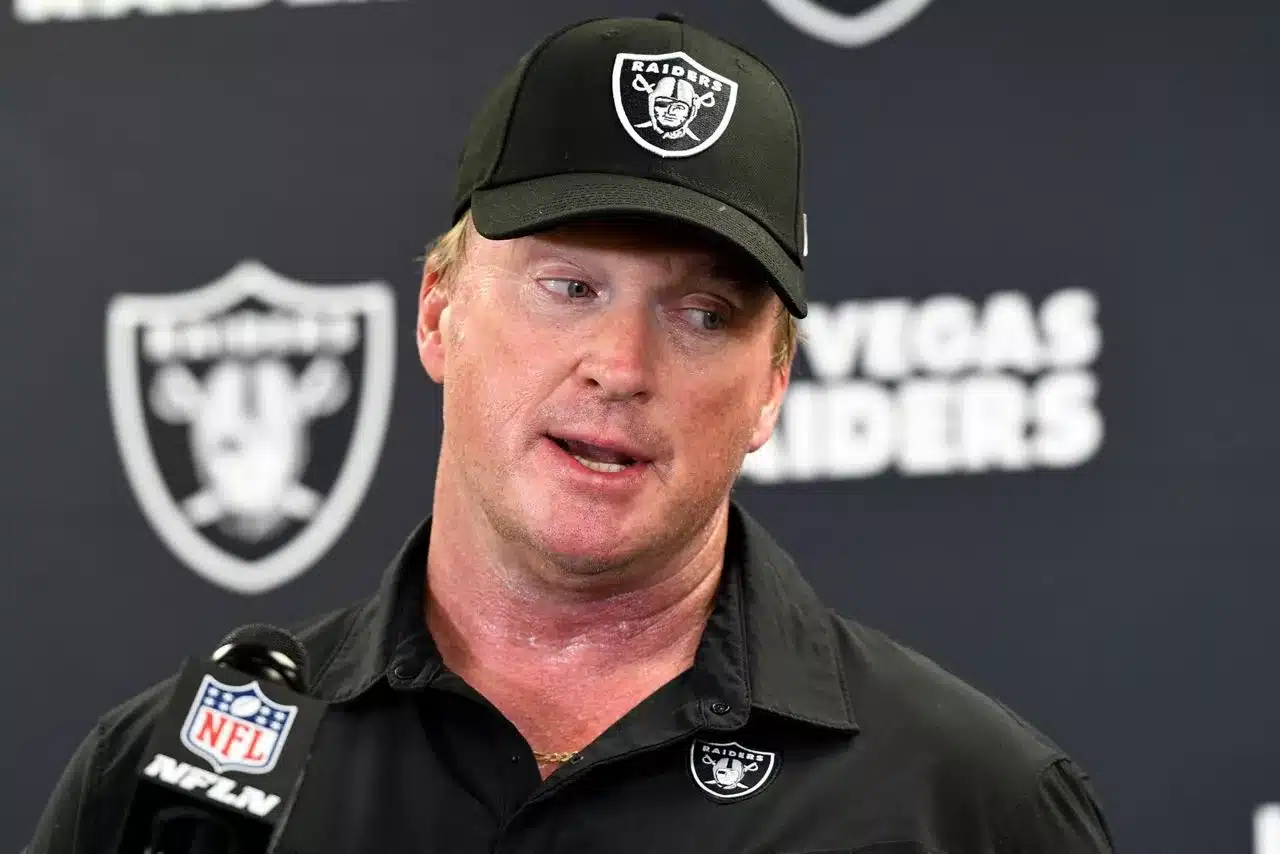

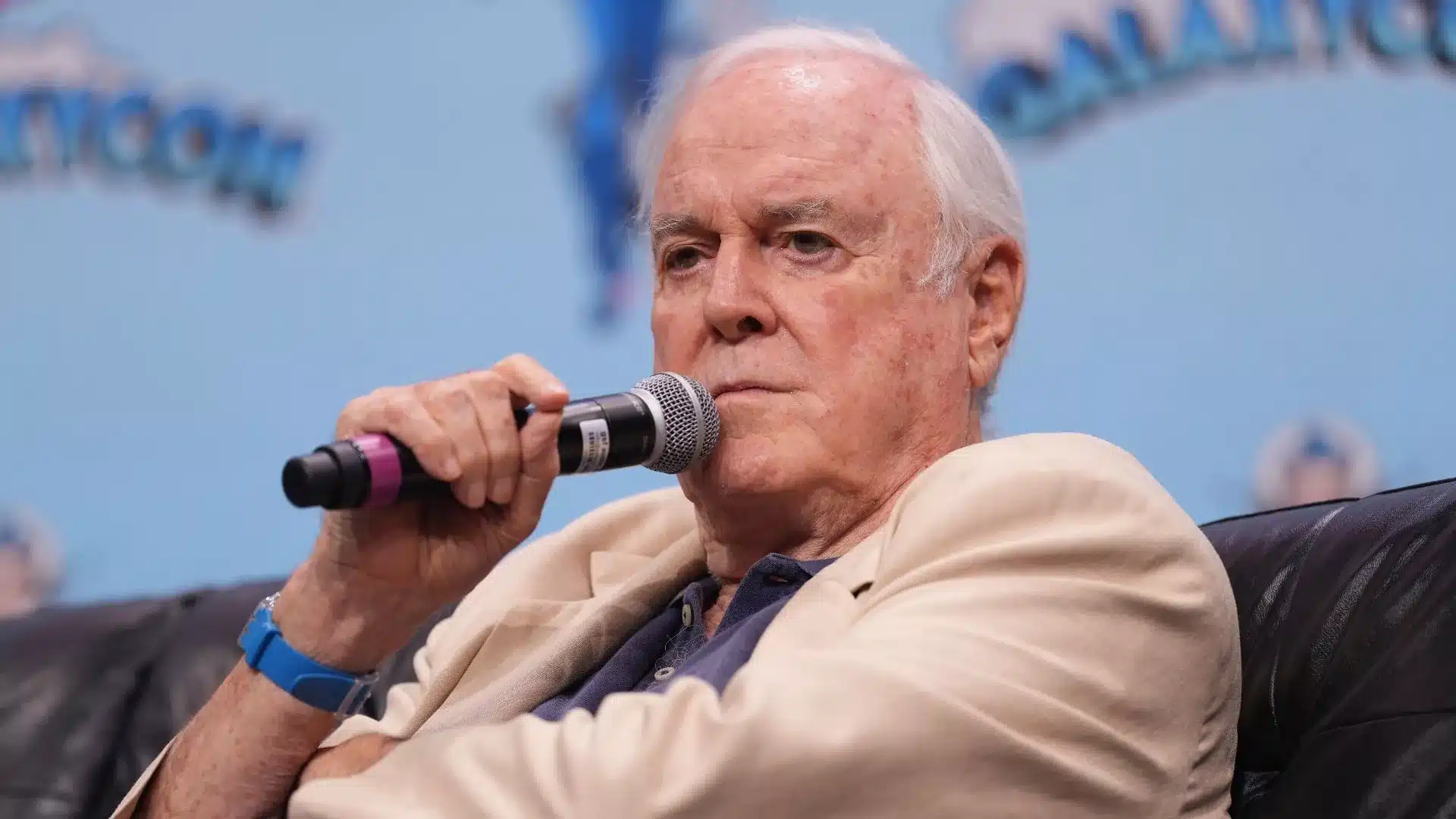

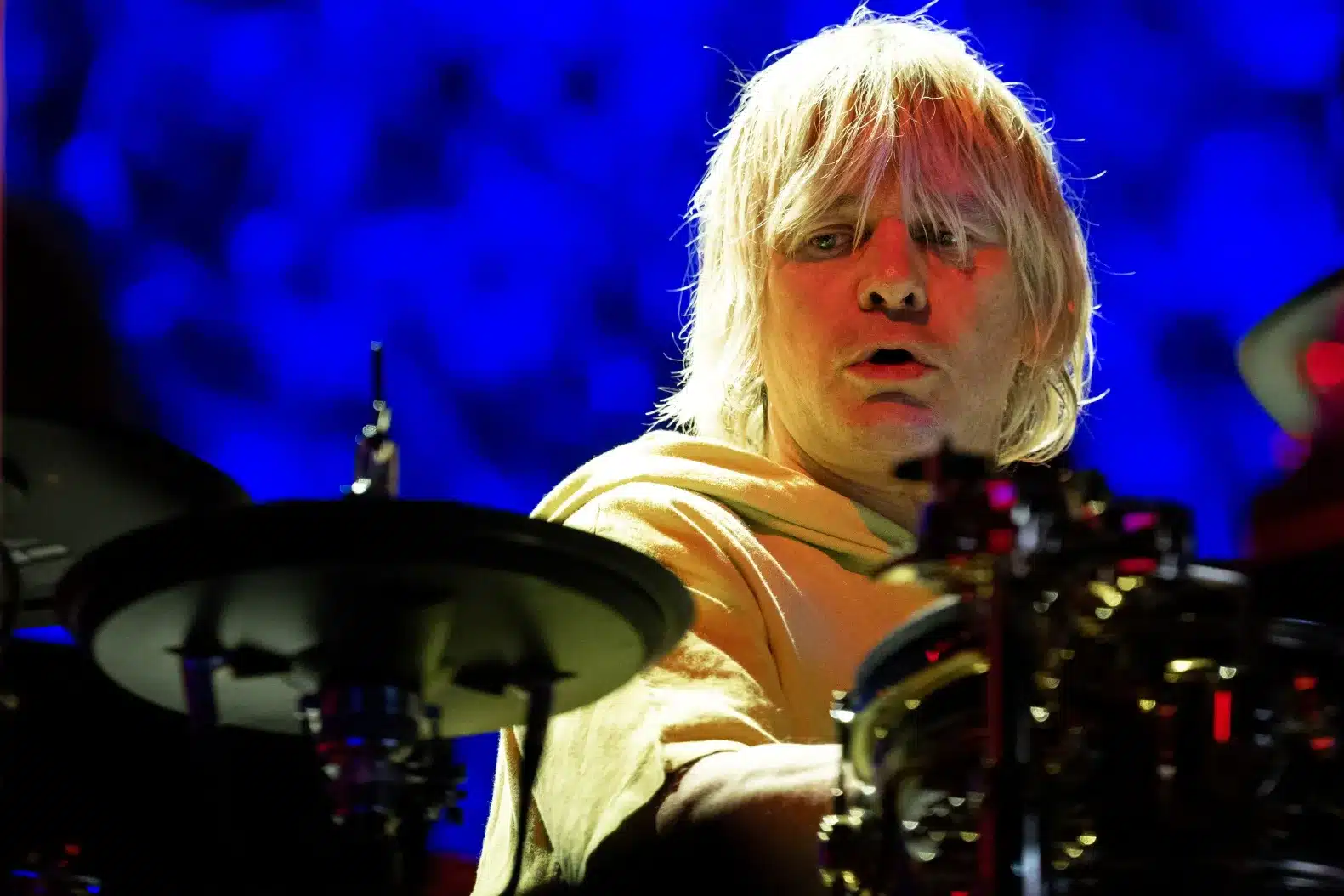

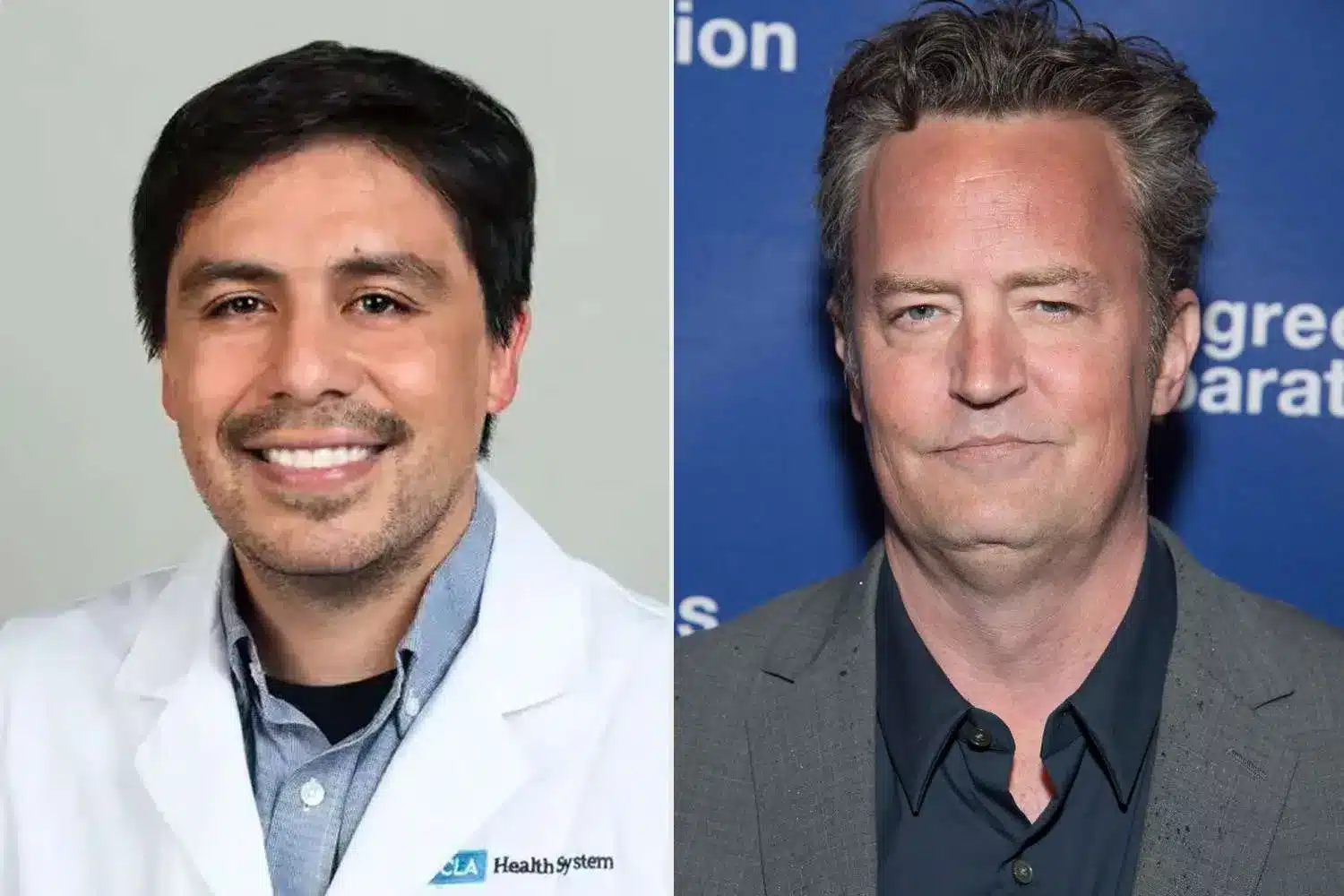

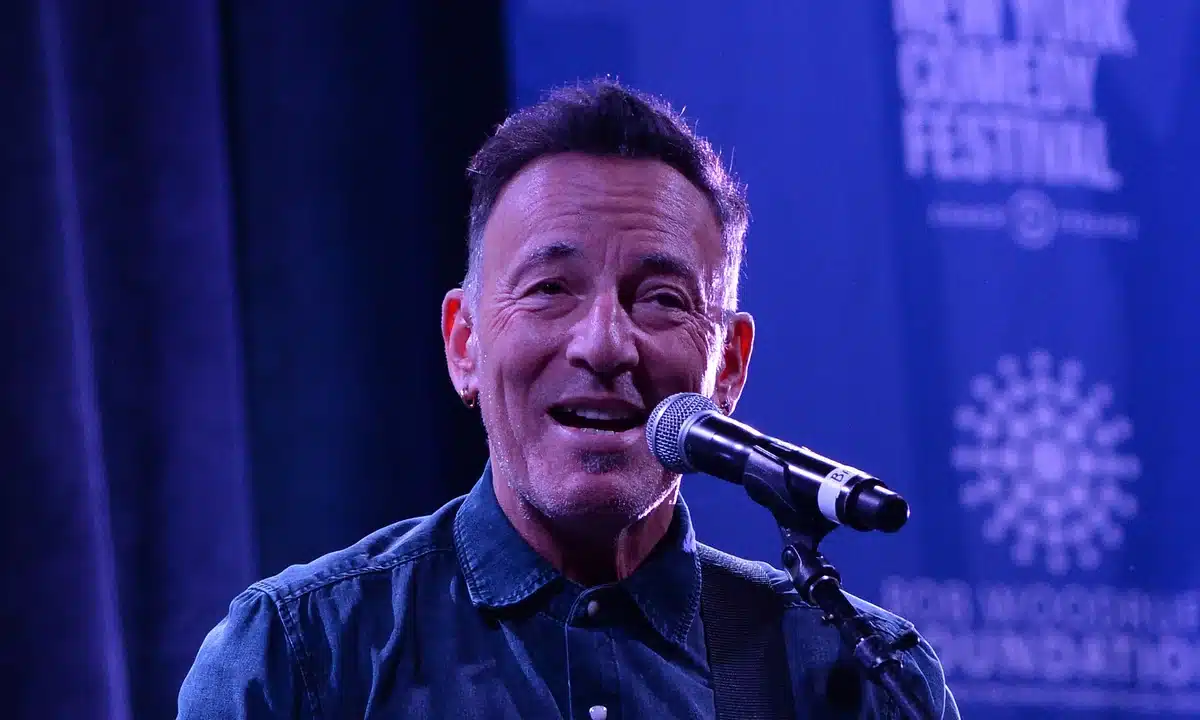

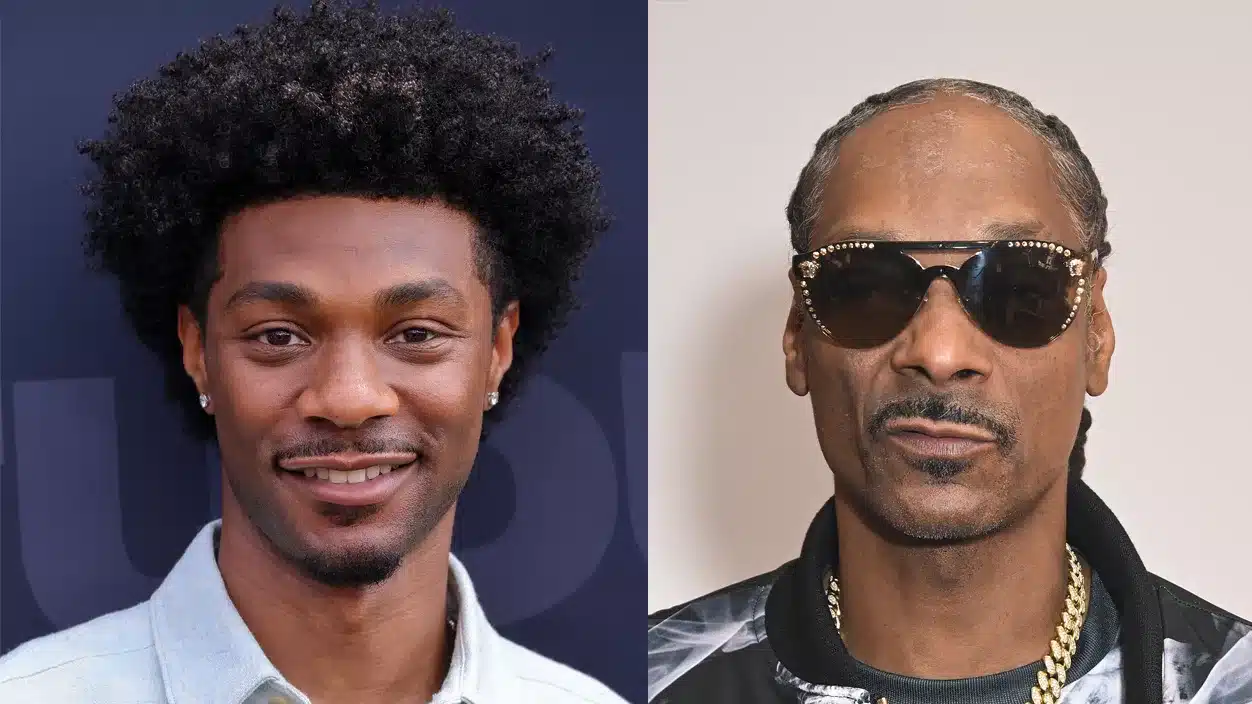

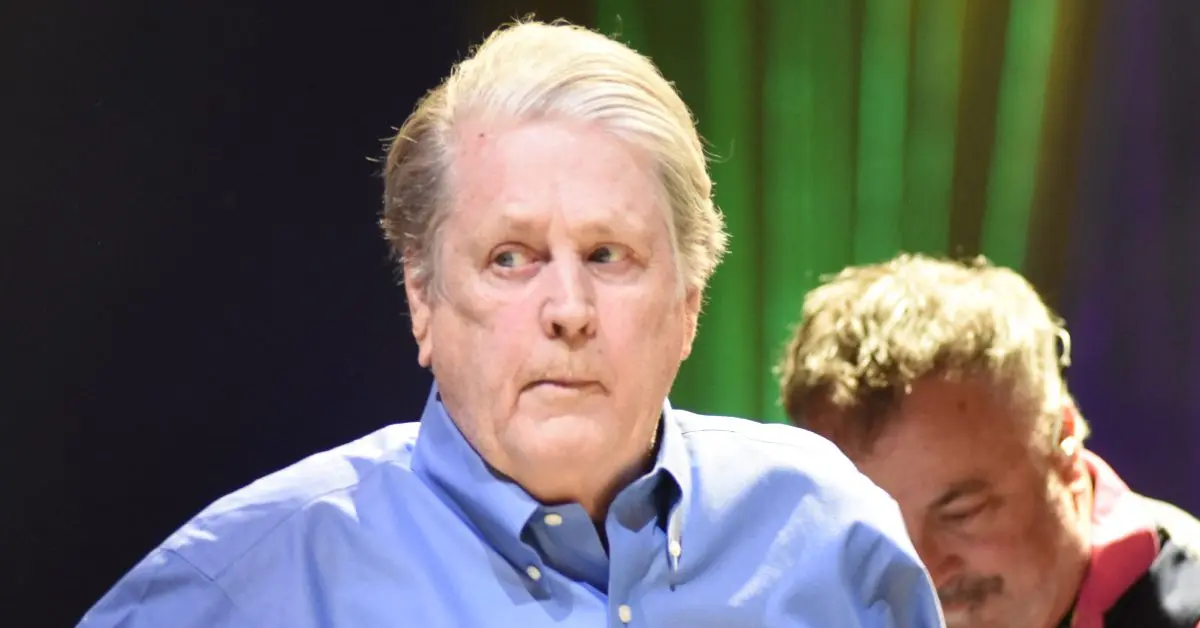

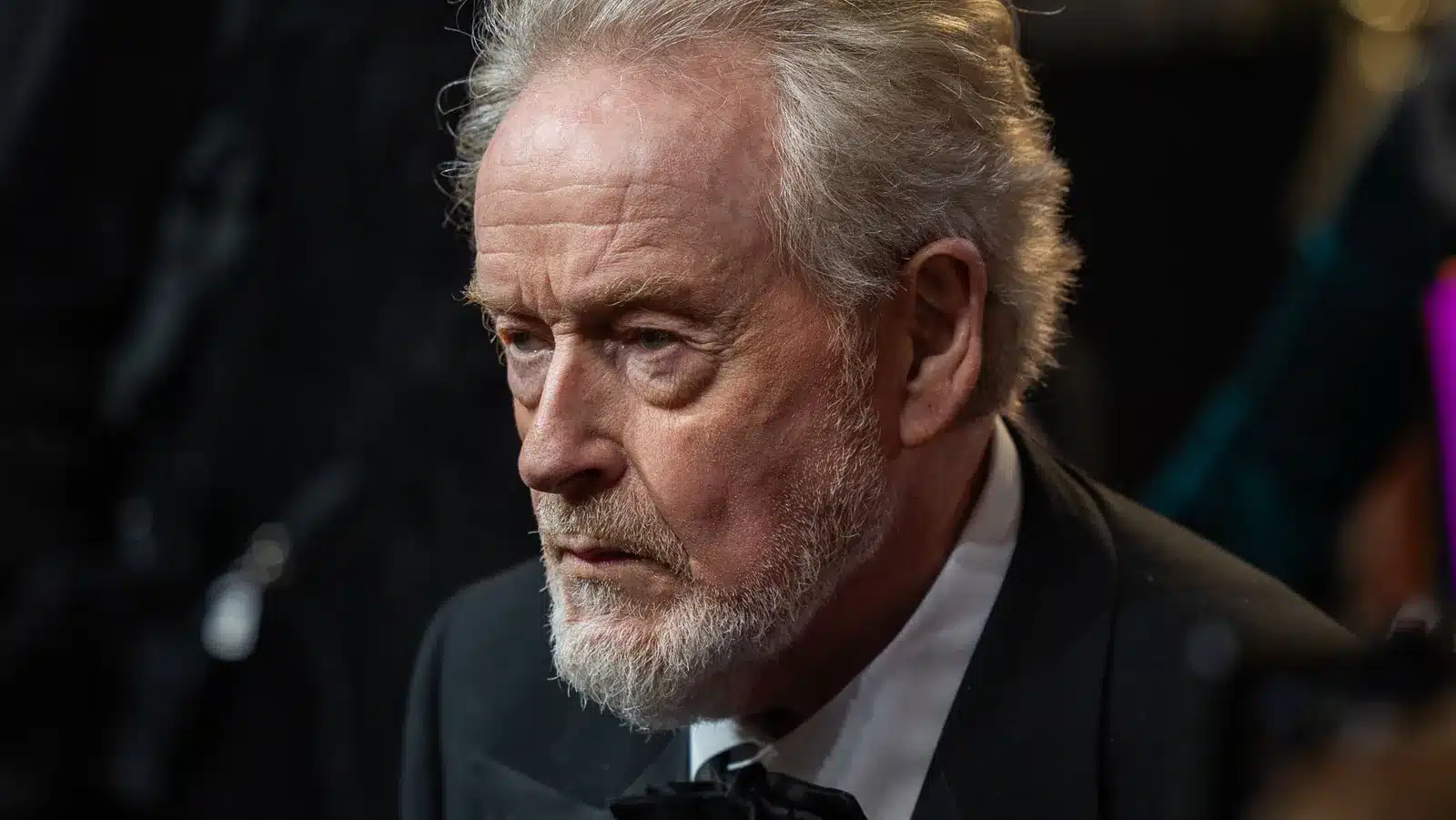

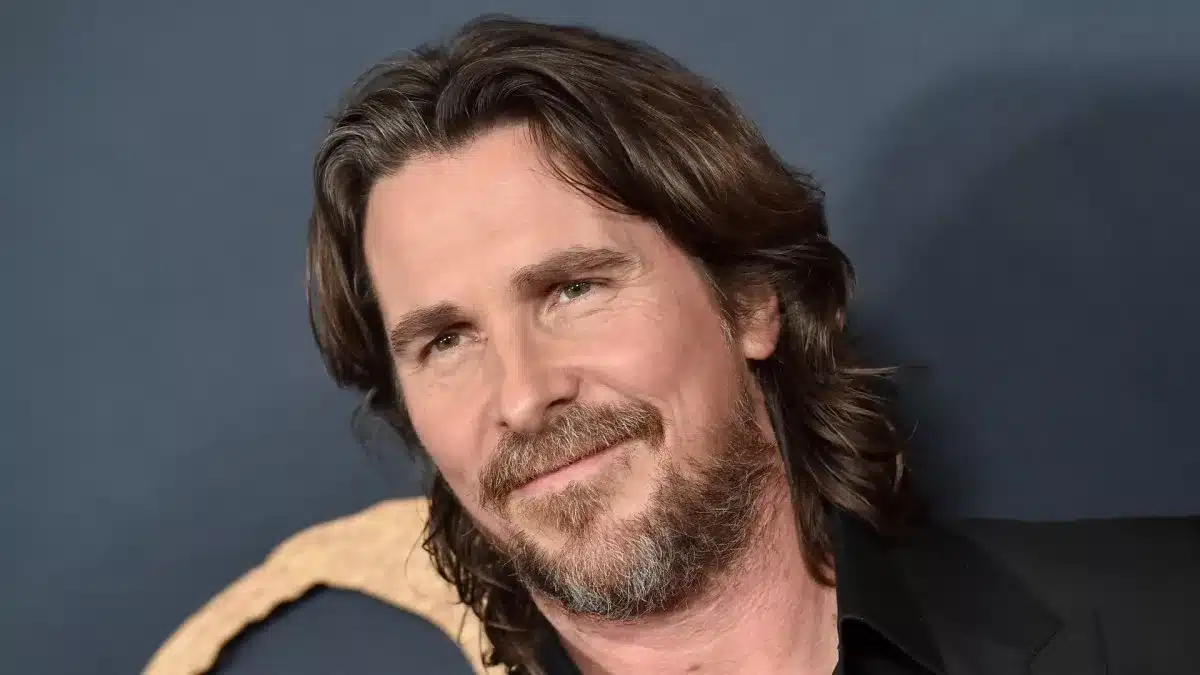

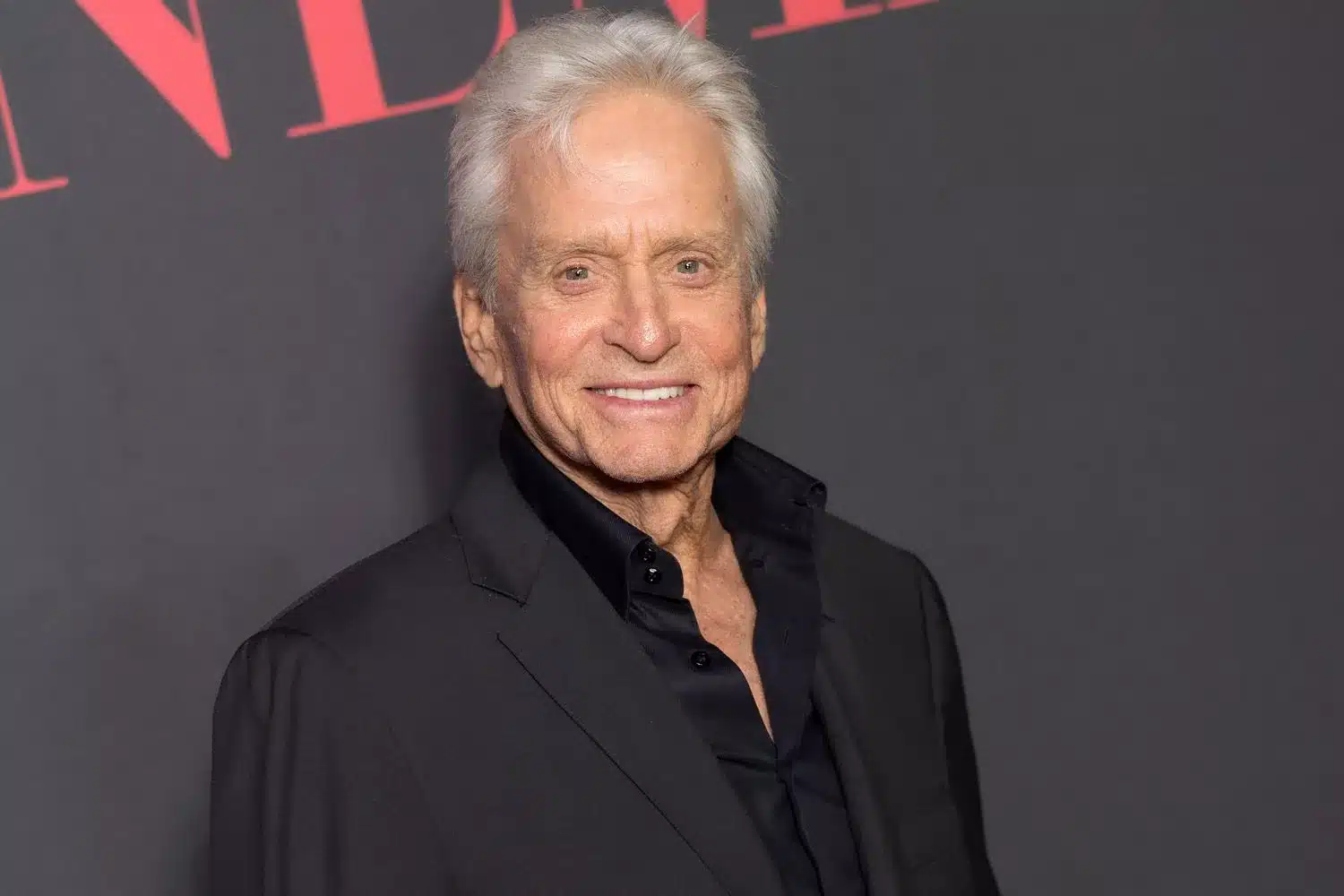

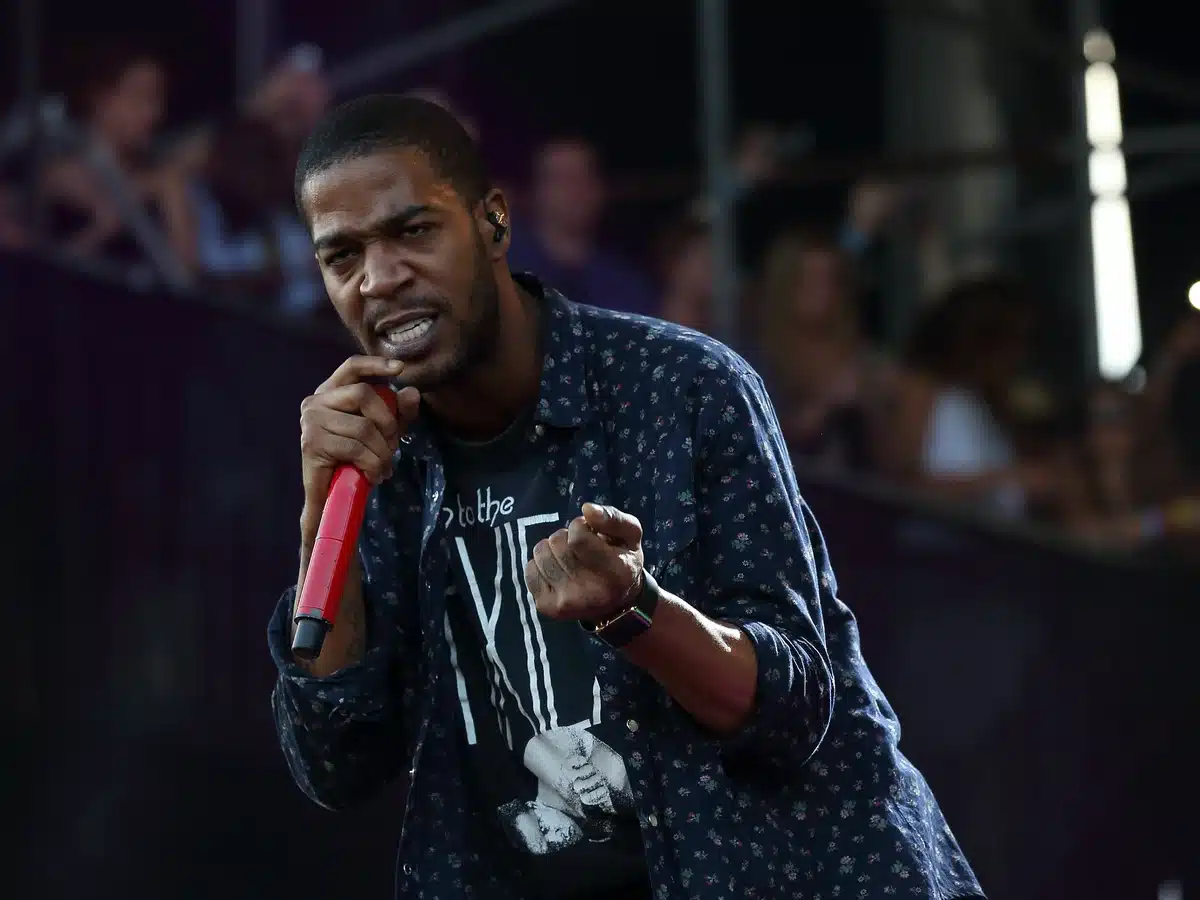

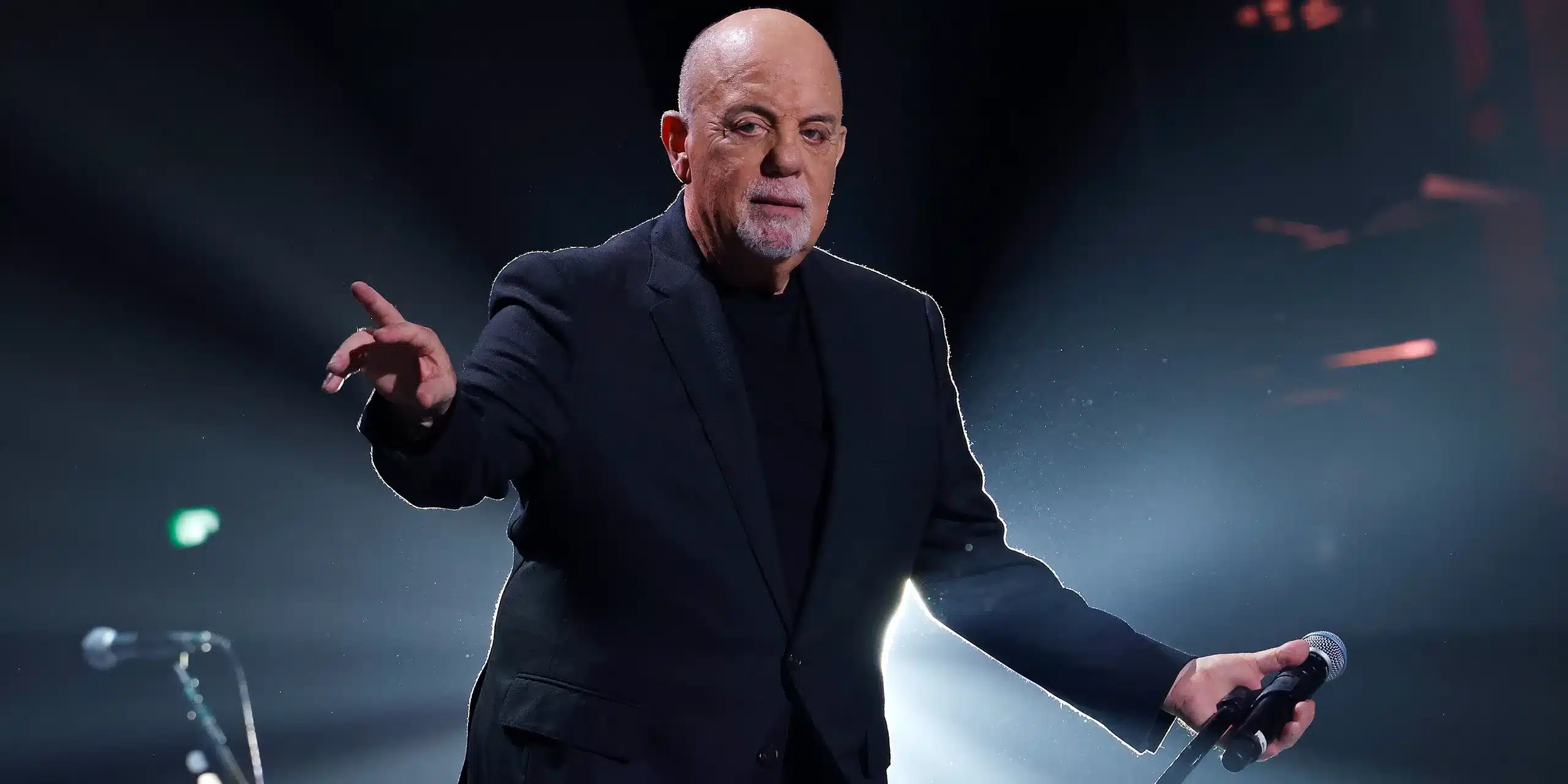

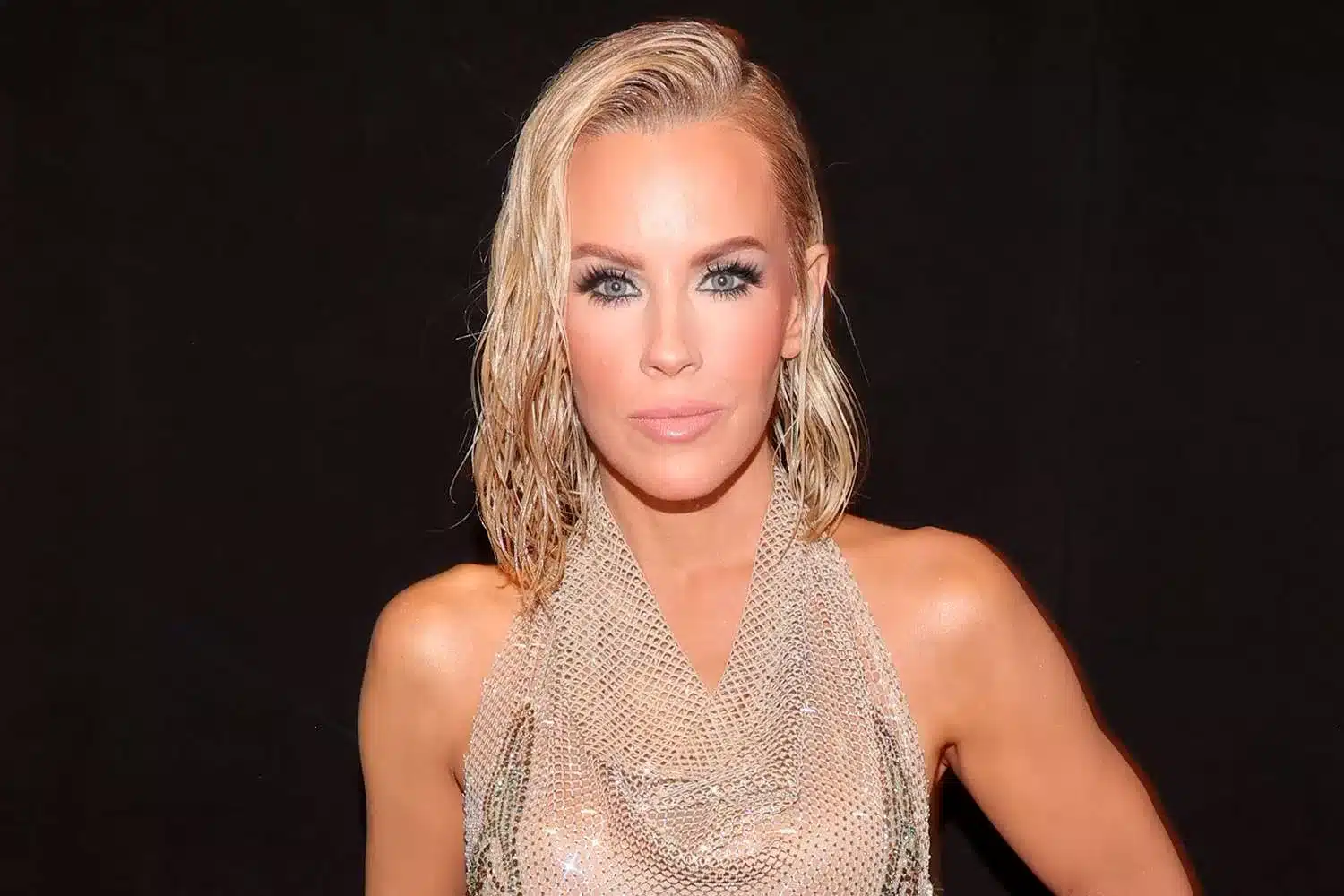

But New York University professor and podcaster Scott Galloway cautioned that the numbers are a false narrative. In his Prof G Markets newsletter, Galloway pointed out that when food, energy, and trade services are stripped away, core PPI actually increased 0.3% in August – its fourth straight month of gains. In his opinion, manufacturers’ expenses continue to be elevated, even if wholesalers and retailers sometimes shave margins to absorb tariffs. Equipment and vehicle margins, for example, dropped 3.9% in a single month, hiding the fact that production costs are going up.

Galloway also cited the Consumer Price Index (CPI), which rose 0.4% in August, to bring the annual inflation to 2.9%. Housing costs were in the lead, followed by airfare, autos, and clothing prices. He contended that the underlying pressure indicates inflation isn’t slowing down nearly as much as the headline figures.

To appreciate his concerns, one must realize what these measures entrap. The CPI accounts for the movement of prices of goods and services that consumers usually purchase, like food, shelter, and gasoline. It is the most popular indicator of consumer inflation. The PPI, however, monitors the price changes firms experience when purchasing raw materials and wholesale merchandise. While it does not directly measure consumer inflation, it is usually a precursor, as companies inevitably pass on increased costs to consumers.

Even as markets cheered the Fed’s move, Galloway pointed out that reducing rates can exacerbate the issue. “Inflation remains 90 basis points above the Fed’s 2% objective,” he said, highlighting that customers keep spending a lot and demand remains robust. He invoked visions of crowded stores in New York City as proof that the demand is not the problem. Rather, he views tariffs and supply-side limitations as the actual cause of higher prices. Raising rates, he reasoned, accomplishes little to correct these issues and might even spur more demand while costs of inputs continue to be high.

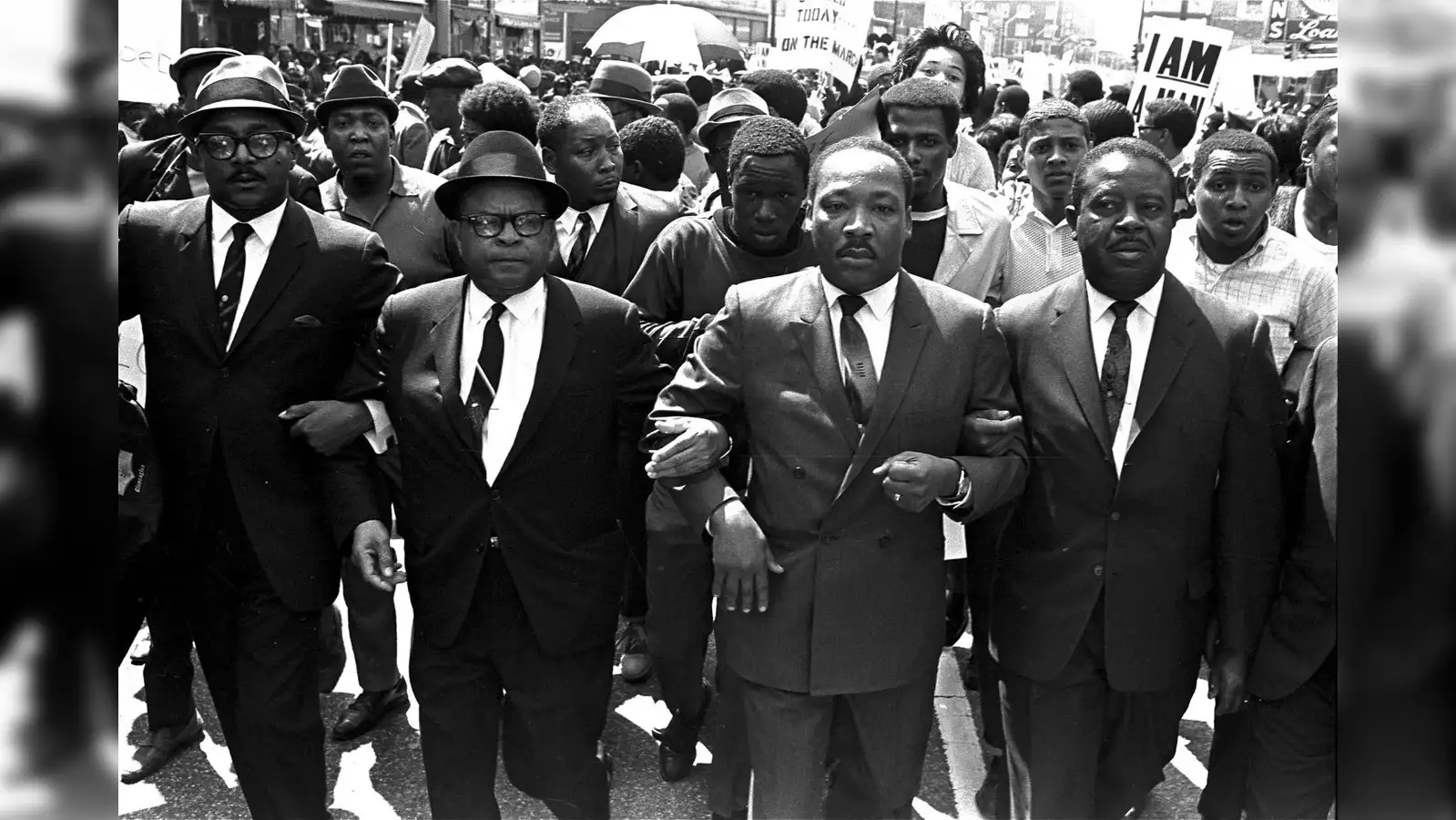

This brings him to his larger concern: stagflation. The 1960s-coined term explains the unusual and agonizing occurrence of slowing growth, increasing unemployment, and inflation. Unlike an average recession, in which decreasing demand means reduced prices, stagflation combines slow growth with escalating prices. America witnessed it in the 1970s, when an OPEC embargo drove energy prices skyward even as growth came to a halt. The crisis resolved only when Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker aggressively increased interest rates in 1979.

Now, Galloway feels supply shocks and tariffs pose the same threats. Stagflation is notoriously difficult to cure because central banks have to decide whether to raise interest rates to combat inflation or lower them to boost growth. Either course of action threatens to exacerbate one issue at the expense of the other. Economists quantify its damage through the “misery index,” which topped historical highs in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

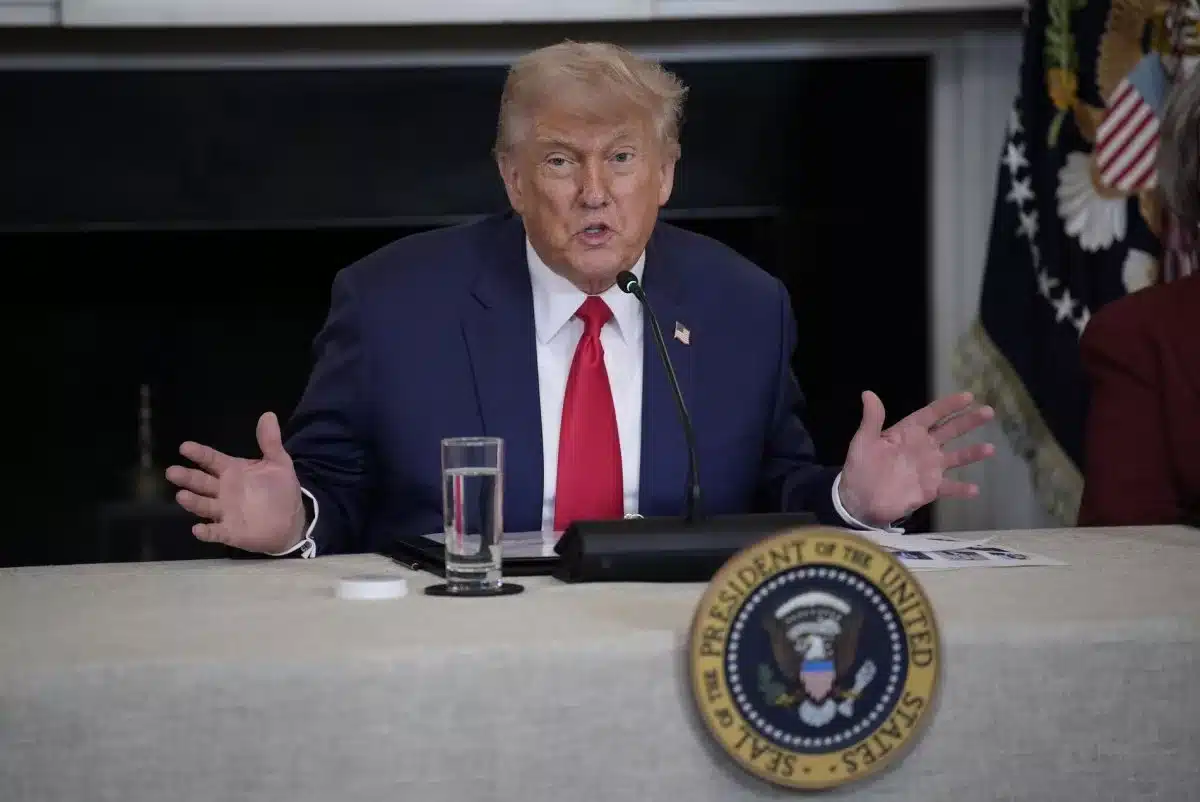

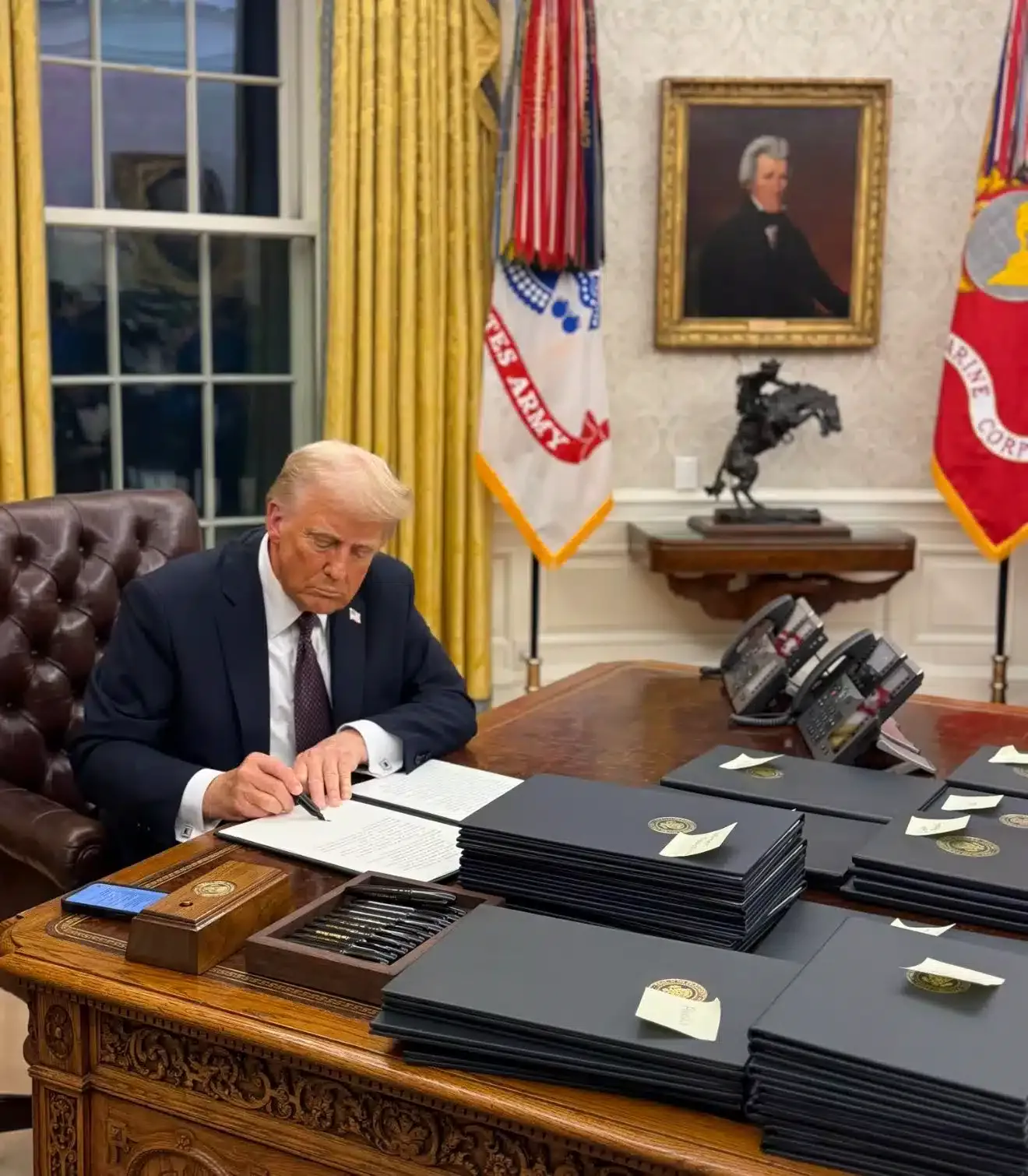

The Fed’s Sept. 17 action came on the heels of eight months of waiting in the wings. Although the 0.25% reduction in the interest rate was modest, most investors had been expecting a bigger cut to offset decelerating labor market trends. Looking forward, there is a division of opinion among Fed committee members: nine anticipate two additional cuts this year, while seven foresee one or none in 2025. The Trump administration has placed added pressure on the Fed, challenging the central bank’s independence in determining monetary policy.

For the moment, investors are optimistic about the short-run impact of cheaper borrowing, but Galloway contends the real problem has not disappeared. Increased input costs, ongoing tariffs, and ongoing CPI increases can still cause Americans to endure a worst-case scenario. If stagflation gains traction, the economic suffering can be considerably worse than the transitory comfort provided by cheaper interest rates.

As Galloway concluded, reducing rates “doesn’t mean it makes sense.” The threat, he cautions, is forgetting the underlying inflationary pressures that are alive and well under the surface.