The story so far:

All is fair in love and war is a phrase that has literary roots and rhetorical appeal, suggesting that in matters of passion and conflict, rules can be discarded, and morality suspended. But in the realpolitik of nation-states, especially when it comes to shared natural resources, such romantic notions may be specious. Water, unlike territory or ideology, is not merely a symbol of sovereignty — it is a lifeline. Now that India has held the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) with Pakistan in abeyance, in the aftermath of the Pahalgam terrorist attack, the question is not only about what is fair but also about what is legal and sustainable. Can water be wielded as a weapon without collateral damage to international credibility and long-term national interest?

What is the history of the treaty?

The IWT was born not out of goodwill, but necessity. In 1947, the Partition carved two nations out of British India but left the rivers of the Indus basin awkwardly distributed. The headworks of the system —crucial for irrigation — fell within Indian territory, while Pakistan was downstream and entirely dependent on river flows. When India briefly halted water supply to Pakistan in 1948, alarm bells rang across the region. It was in this context that the World Bank stepped in to mediate what has now become one of the most successful water-sharing agreements in modern history.

Signed in 1960, the IWT allocated the eastern rivers — the Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej — to India, and the western rivers — the Indus, Jhelum, and Chenab — to Pakistan, while allowing India certain non-consumptive uses such as generating hydropower, provided they meet stringent design and operational conditions. It was a carefully calibrated compromise that reflected not just geography, but also the broader imperative of regional stability.

The treaty has withstood three major wars (1965, 1971, and 1999), repeated border skirmishes, and complete diplomatic breakdowns. Its durability lies in its technical framing and the insulation it provides from political upheavals. Annual meetings between the Permanent Indus Commissions continued even during times of war. The IWT’s dispute resolution mechanism — which includes bilateral consultations, neutral expert analysis, and, if needed, mediation through a Court of Arbitration— has enabled the treaty to function despite deep mistrust between the two countries.

Yet in recent years, the insulation of the IWT from larger geopolitics has come under increasing strain.

What about India’s hydro-infrastructure development projects?

India’s renewed scrutiny of the IWT has come in the wake of terrorist attacks which have been claimed by Pakistan-based groups. The 2016 Uri attack and the 2019 Pulwama bombing catalysed calls from within India to re-examine the treaty. Some voices, particularly in political circles, suggested that water could be used as leverage, arguing that it was morally untenable to continue honouring an agreement with a state that encourages cross-border terrorism.

This shift in tone has coincided with India’s increasing hydro-infrastructure development in Jammu and Kashmir. Projects like the Kishanganga (on the Jhelum) and Ratle (on the Chenab) hydroelectric plants have been flashpoints of contention between both countries. While India insists these are compliant with treaty provisions, Pakistan argues that the design features give India excessive control over water flows, especially during the lean season — potentially threatening Pakistan’s agricultural and ecological security.

Pakistan has, therefore, invoked the IWT’s adjudicatory mechanisms. In the Kishanganga dispute, Pakistan challenged India’s diversion of water to a power plant. The Court of Arbitration, constituted in 2010, ruled in 2013 that India could proceed with the diversion, provided that it maintained a minimum downstream flow. The court also imposed limits on how India could manage its reservoirs.

In the Ratle case, a fresh procedural conflict emerged. India sought the appointment of a neutral expert, considering it a technical issue while Pakistan wanted a Court of Arbitration. In 2016, the World Bank, tasked with administering the treaty’s dispute process, paused both requests to avoid parallel proceedings. However, in 2022, it allowed both to go forward, prompting India to boycott the arbitration proceedings while participating in the neutral expert process.

This precedent is significant. It confirms that the legal architecture of the IWT is not only active but likely to be triggered again if India were to withdraw from the treaty. Far from giving India decisive leverage, such a move could backfire by inviting a flurry of legal, diplomatic, and reputational consequences.

Can a third party mediate?

India has long maintained, especially since the Simla Agreement in 1972, that all disputes with Pakistan must be resolved bilaterally. This has been New Delhi’s consistent position, particularly with regard to third-party mediation on Kashmir.

However, the IWT predates the Simla agreement and contains its own provisions for third-party adjudication. Neutral experts and arbitrators are not external interlopers but treaty-sanctioned mediators agreed upon by both parties. India’s participation in the Kishanganga arbitration and the neutral expert process for Ratle — however begrudgingly —acknowledges this reality. The invocation of the Simla agreement cannot nullify what the IWT permits.

What about other such disputes?

Inter-country water disputes are not unique to South Asia. Europe, too, has witnessed water tensions, particularly in the aftermath of war. After World War I, disputes arose between Hungary and Czechoslovakia over the use of the Danube river. These were largely managed through negotiated settlements under the League of Nations framework. More recently, the Gabčíkovo–Nagymaros case between Hungary and Slovakia, related to a dam project on the Danube, was taken to the International Court of Justice (ICJ). The ICJ ruled in 1997 that both parties had breached aspects of their treaty obligations and urged cooperative implementation. Though slow, the resolution process underscored the importance of legal frameworks over unilateral action.

Another example is the Mekong river dispute in Southeast Asia. Countries like Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam, and Thailand share this crucial river, and tensions have flared over hydropower projects. Yet the Mekong River Commission, a multilateral framework for dialogue, has helped avert conflict through transparency and data-sharing.

In both cases, the central lesson was this: when nations retreat into unilateralism, the result is stalemate or escalation. But when legal and diplomatic channels are preserved, even deeply rooted disputes can be managed — if not fully resolved.

What are the risks of withdrawing from the IWT?

Unilaterally withdrawing from the treaty would likely invite sharp international censure. India’s image as a responsible regional power would be undermined, especially at a time when it seeks a greater role in global governance. The World Bank, which served as guarantor to the treaty, would be compelled to intervene diplomatically, if not legally. Such a move could also alarm neighbours in the Himalayan basin, such as Nepal and Bangladesh, who might become vary about any future water cooperation.

Legally, the IWT is a binding international treaty. There is no provision for withdrawal. Under the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, unilateral exit is only possible under extreme and narrowly defined circumstances.

Moreover, water is not just a strategic asset — it is a basic human right. Using it as an instrument of retaliation raises ethical questions that go beyond borders. Cutting off or even reducing water flow could devastate downstream communities, especially during lean periods. Even in the theatre of national security, collective punishment violates moral norms. India’s true strength lies not in weaponising water, but in showcasing its commitment to a rules-based order.

What should be done?

India has every right to maximise its permitted usage under the IWT, including building hydropower projects within the framework of the treaty. It has already done so in Kishanganga, and is doing so in Ratle —albeit amid legal contestation. But abandoning the treaty would erode legal high ground and may place India on the defensive internationally.

The IWT stands as a rare monument to cooperation in an otherwise fractious relationship. It demonstrates that even in adversarial contexts, nations can agree to share what is vital and sacred — water. To undo that would not only undermine decades of diplomacy but also set a dangerous precedent for how natural resources are used — or misused— in conflict zones.

In war, not all may be fair, and in love for peace, some things must remain sacred.

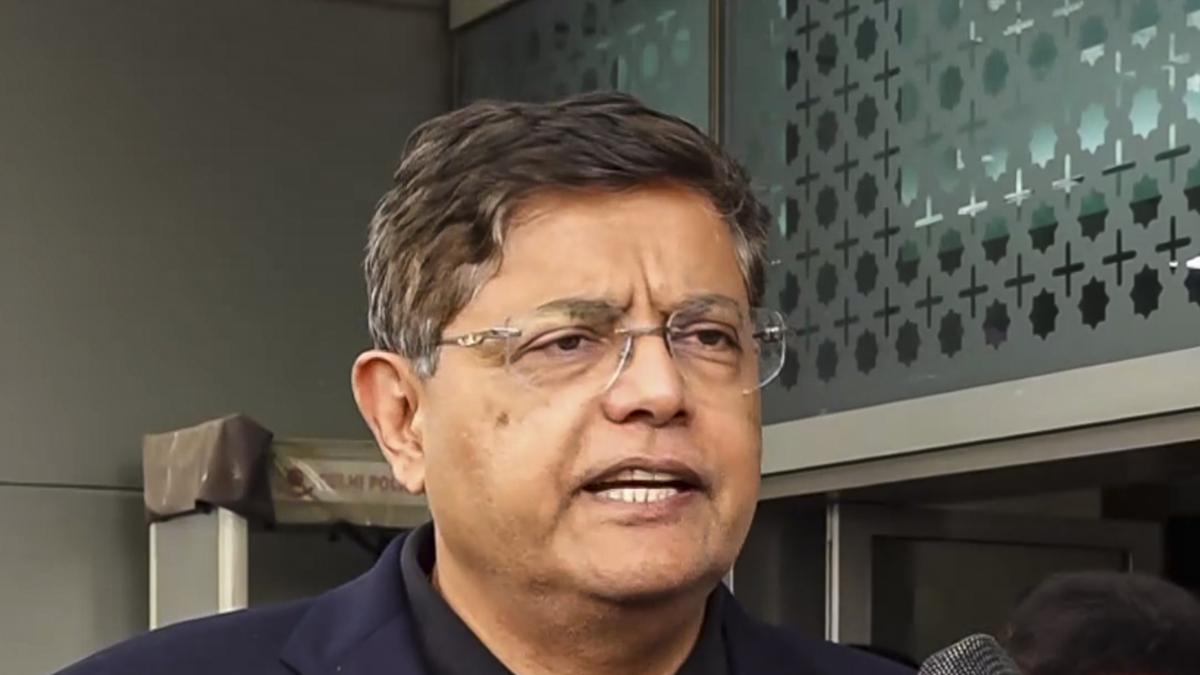

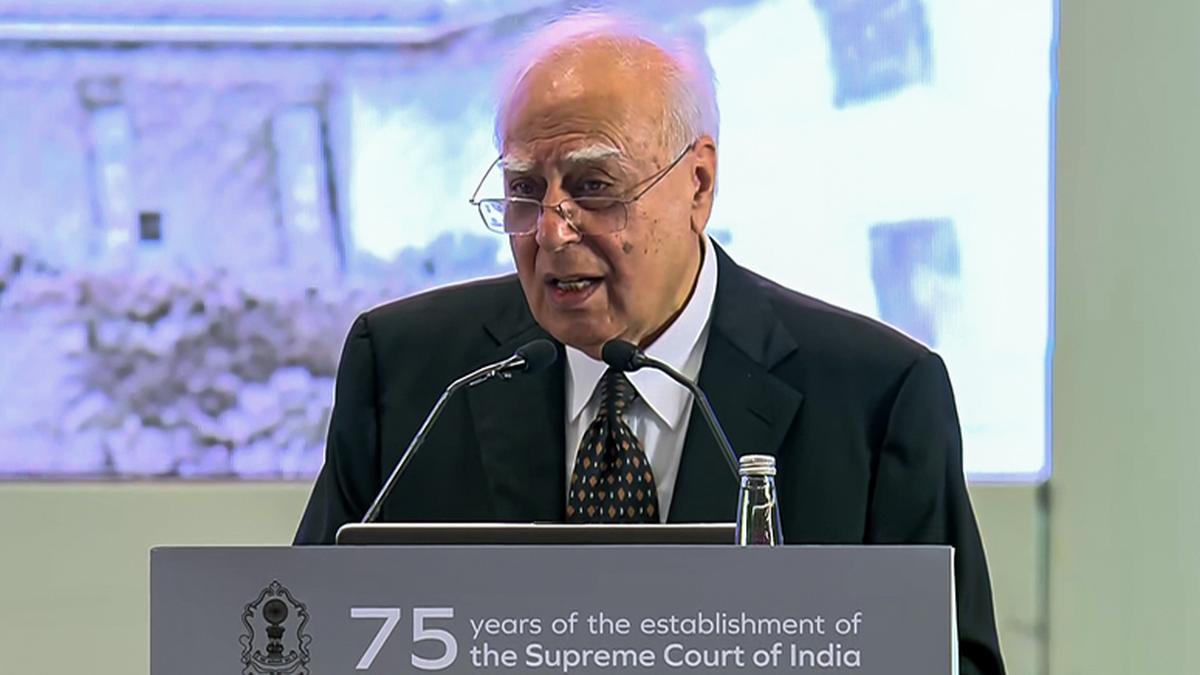

K. Kannan is Senior Counsel/mediator and a former judge of the Punjab and Haryana High Court.

Published – May 22, 2025 08:30 am IST