In Pedavegi, a non-descript dot on the map of West Godavari district in what was then undivided Andhra Pradesh, an act of symbolism took root, literally, way back in 1986. Then Chief Minister N.T. Rama Rao knelt on a patch of farmland and planted a palm sapling. At that point, it may have seemed like just another photo op. But that simple act would outgrow its moment in history, rooting itself into the soil, and the future, of two States.

Four decades later, that one sapling has morphed into a sweeping oil palm culture that now sustains thousands of farmers across Andhra Pradesh and Telangana.

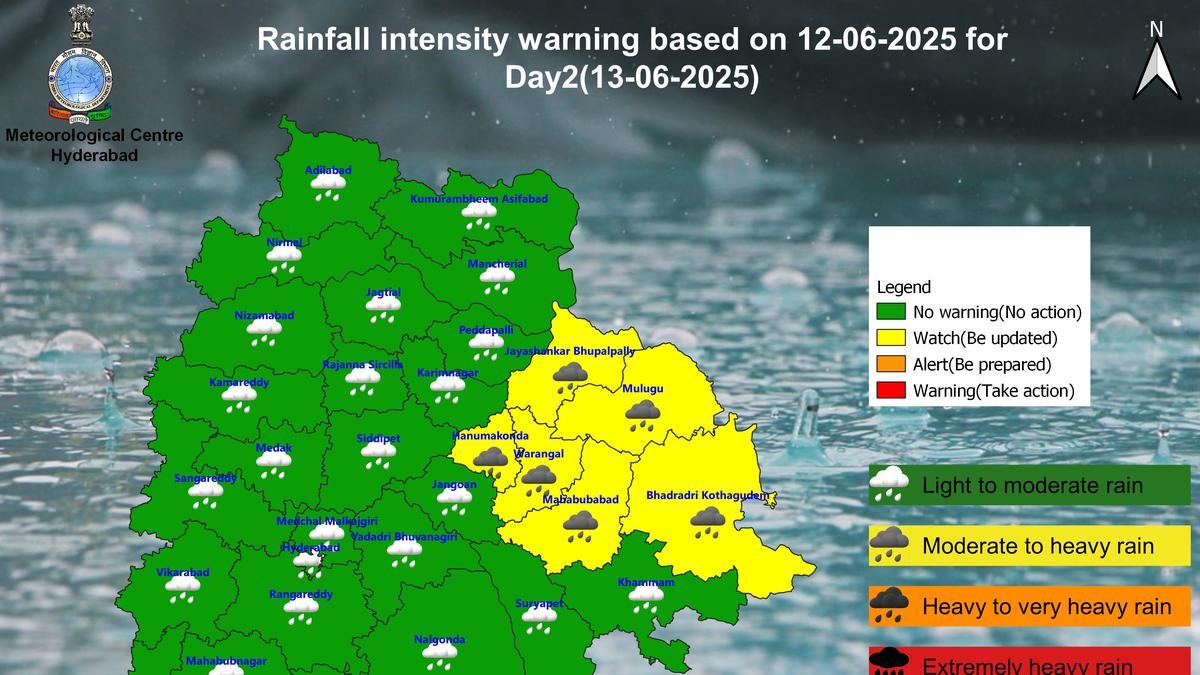

What started in the lush delta districts of West and East Godavari soon crept into Krishna, before leaping across the newly-drawn State borders into Telangana. Khammam was the first to embrace it, followed by Adilabad and Nalgonda, where farmers looked westward for inspiration, and returns too.

Among the early adopters was Gutta Venkatarama Rao, a farmer from Malkaram village in Dammapeta mandal, now in Telangana’s Bhadradri Kothagudem district. He vividly remembers the early 1990s, not just for the gamble he took, but also for what it gave back.

“It was N.T. Rama Rao’s vision of promoting oil palm cultivation that lit the spark,” says the 69-year-old. “He wanted farmers to have a stable income and the country to become self-reliant in edible oil. That is what pushed me to plant oil palm in 1994.”

And that decision paid off. For over two decades, oil palm gave him what few crops could: predictability, prosperity and peace of mind. His success did not go unnoticed. Soon, other farmers in Dammapeta followed, turning the region into a hub for oil palm cultivation.

It wasn’t long before word spread beyond Dammapeta and Aswaraopeta, also in the same district. Farmers from across the State began travelling to these mandals to see the transformation firsthand. Among them was V. Veerya, a tribal farmer from Singaram village in Mahabubabad district.

Once a chilli grower, Veerya had battled erratic yields and constant crop damage by monkeys. But after a study tour to the oil palm heartlands in 2019, he returned home with a plan, and four acres of land waiting to be repurposed. “Seeing what they had built there, it opened my eyes,” he recalls. With support from the Horticulture Department and subsidies for seedlings and drip irrigation, he made the switch.

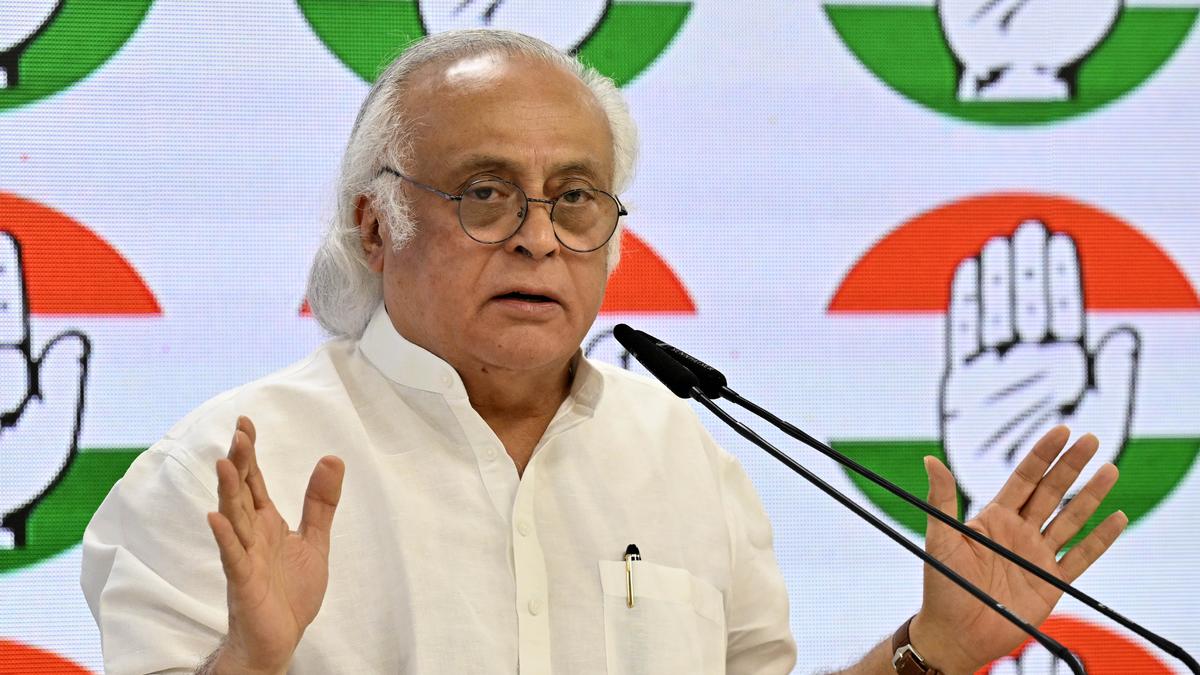

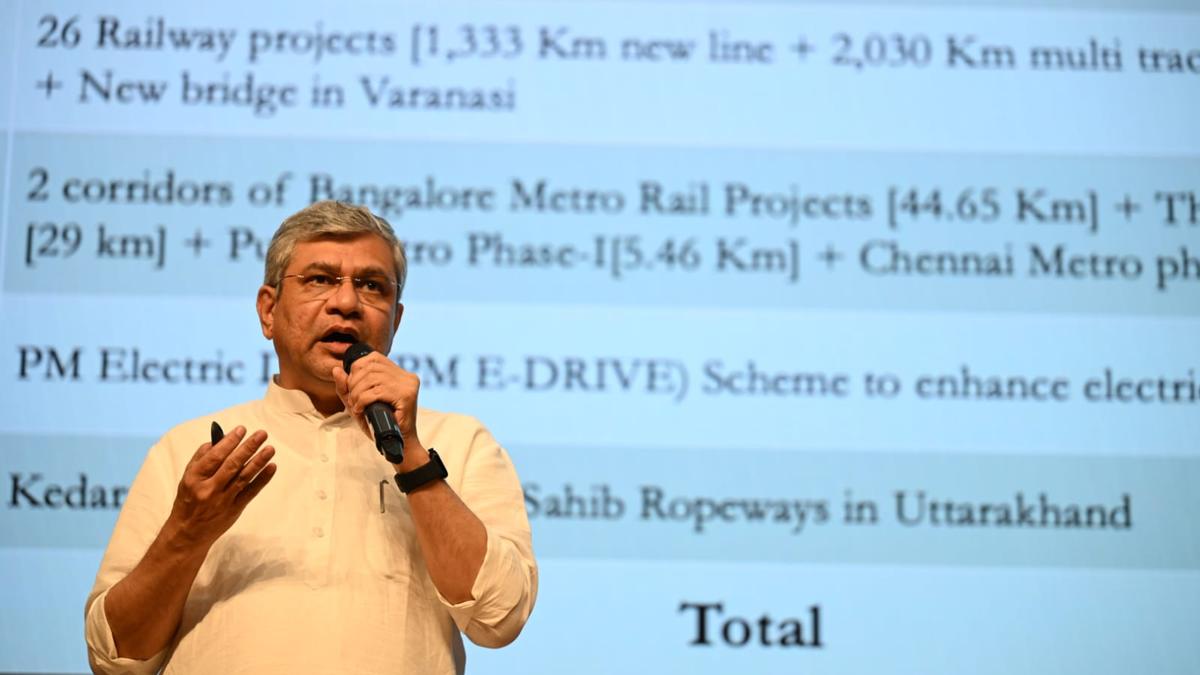

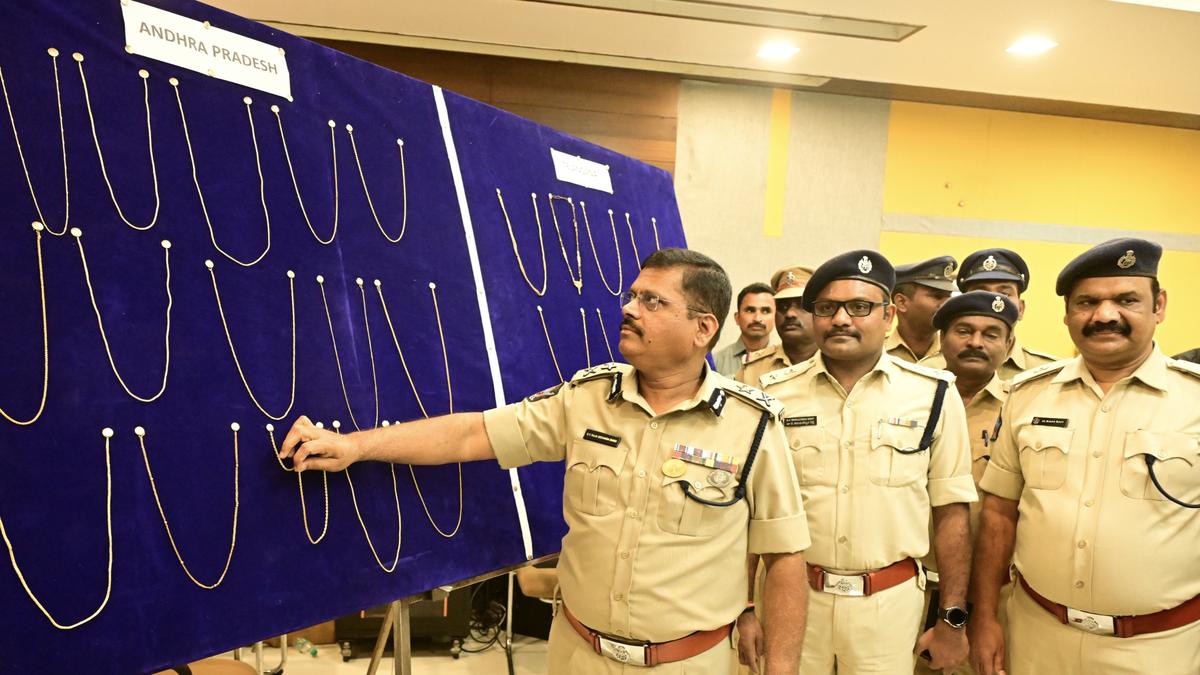

A man working at an oil palm farm in Allipuram of Khammam district.

| Photo Credit:

File Photo

Today, the results speak for themselves. On June 10 this year, Veerya harvested his first oil palm crop — six tonnes of fresh fruit bunches. “It not just a harvest, it is security. No longer do I have to fear not having a sustainable income.”

From trial to triumph

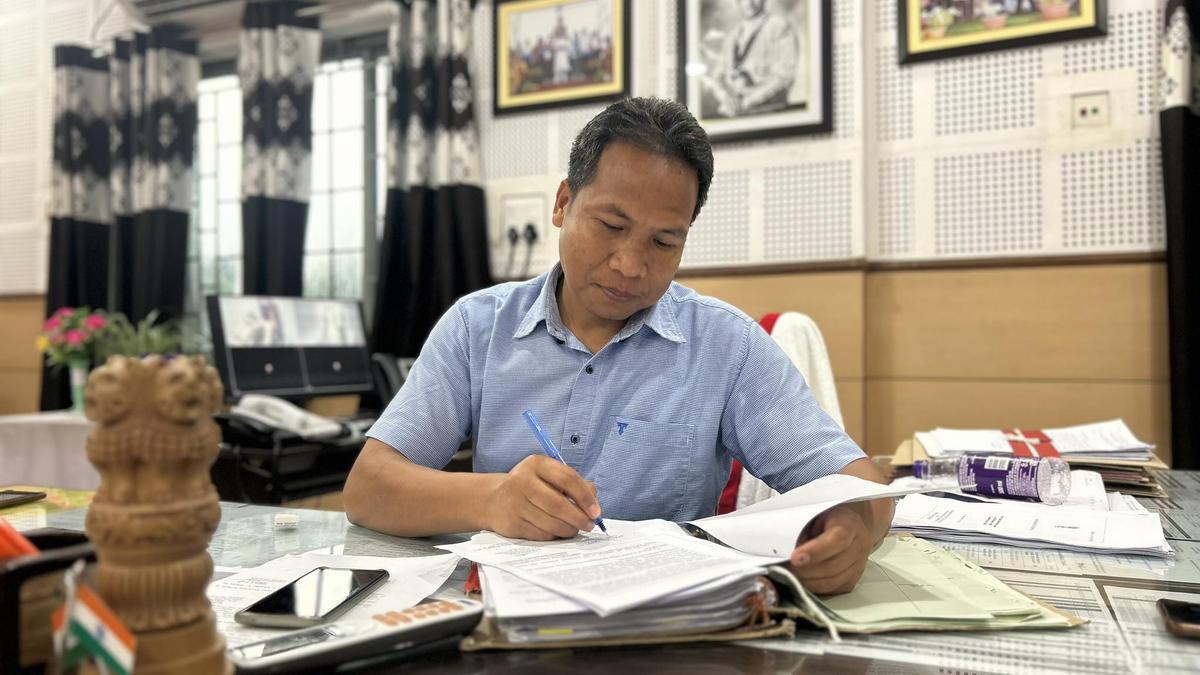

What’s fuelling this quiet agricultural shift is not just curiosity, it is a strong support system backing the crop. Subsidies, assured buyback arrangements, functional processing units and a farmer-friendly environment have turned oil palm into a serious option in Mahabubabad district, says District Horticulture and Sericulture Officer J.Marianna.

Exposure visits to oil palm clusters in Aswaraopeta and Dammapeta gave local farmers more than just inspiration; they offered a hands-on understanding of the crop’s lifecycle, from planting to profit. The district now plans to ramp up cultivation from 8,000 to 12,500 acres in the 2025-26 financial year. To ease the transition, farmers are being offered ₹2,100 per acre annually for the first four years to support intercropping while the palms mature.

Meanwhile, Bhadradri Kothagudem continues to lead Telangana’s oil palm march, with over 75,000 acres already under cultivation. The goal is to expand to one lakh acres and make the crop a central pillar of rural income. The district’s edge lies not just in its soil and climate, but also in infrastructure — two factories run by the Telangana Co-operative Oil Seeds Growers Federation at Aswaraopet and Apparaopeta, capable of crushing 30 tonnes and 60 tonnes of Fresh Fruit Bunches (FFBs), respectively, per hour, ensure that farmers have a reliable place to process their harvest.

In the districts of Nalgonda and Suryapet — regions better known for their citrus orchards — a new class of oil palm growers is emerging. From NRIs and retired officials to big landowners, many are making the switch, drawn by the promise of higher returns. “In four years, oil palm can fetch ₹1 lakh per acre in profit,” explains Narasimha Reddy, vice-president of the Nalgonda Oil Palm Farmers Association, adding, “That is nearly three times what paddy offers.”

But even here, challenges remain. A lack of trained harvesters has forced farmers to pay up to ₹1,200 a day per labourer to cut the heavy bunches. “We need to set up processing facilities and train locals to ease this burden,” Reddy says.

Still, the numbers tell a story of momentum: from 2016-17 to 2024-25, over 10,800 acres in Nalgonda have been brought under oil palm, cultivated by some 2,450 farmers.

Returns, resilience and ripple effect

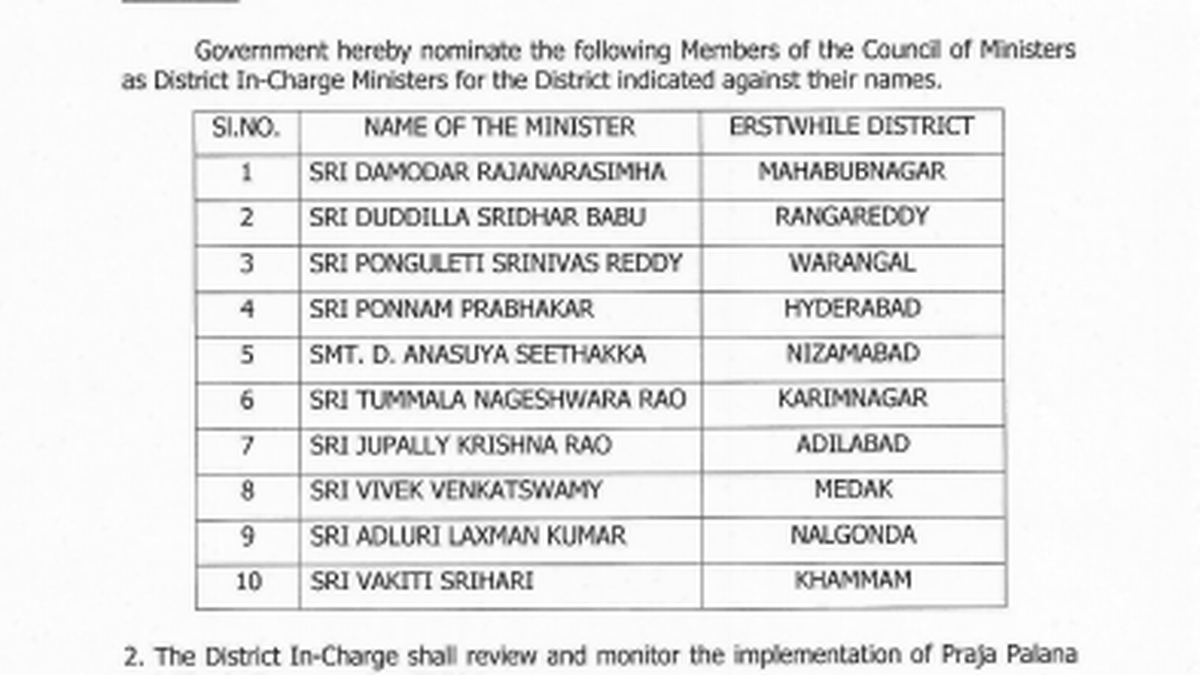

Backed by policy muscle and political will, Telangana is now betting big on oil palm. Under the Telangana State Oil Palm Mission, which is part of the National Mission on Edible Oils-Oil Palm (NMEO-OP), the government has unveiled an ambitious plan: expanding cultivation from the existing 2.45 lakh acres to 20 lakh acres.

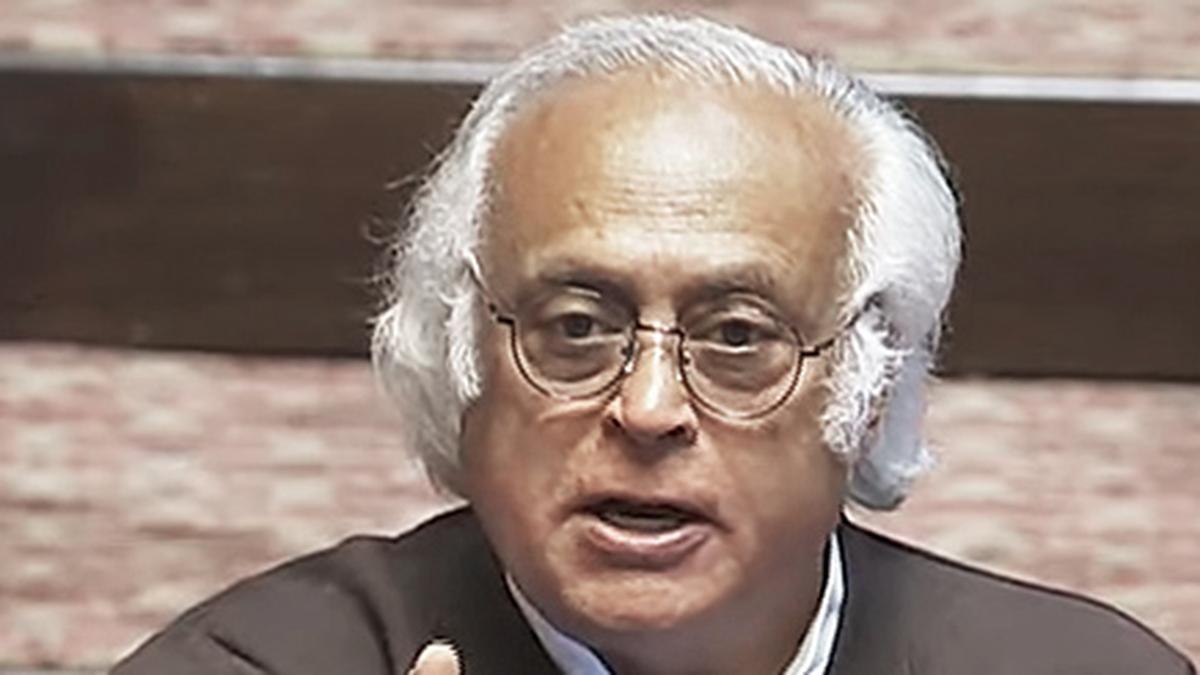

To make this leap, the State has done more than roll out subsidies. It has opened farmers’ eyes to the possibilities. In a strategic move, delegations of farmers and officials were sent on exposure visits to countries like Malaysia to understand modern oil palm farming techniques. The initiative was led by Agriculture Minister Tummala Nageshwar Rao, who hails from Khammam, the district where Telangana’s oil palm journey began.

Even during the BRS regime, the push was palpable. Then-MLA Balka Suman not only championed the cause but led by example. He launched oil palm cultivation on 20 acres of his own land, sparking a ripple effect among neighbouring farmers.

At a recent awareness event in Husnabad of Karimnagar district, Minister for Backward Classes Welfare and Transport Ponnam Prabhakar pitched oil palm as a resilient, high-return crop. “It keeps monkeys at bay and withstands unseasonal rains and hailstorms, which are major concerns for our farmers,” he had said, highlighting income potential ranging from ₹60,000 to ₹1.5 lakh per acre annually.

The numbers back the intent. Since 2022, the State has aggressively expanded cultivation across 26 districts, targeting five lakh acres by 2025 out of a total identified potential of 20 lakh acres — an exponential leap from just 45,000 acres in 2014. The NMEO-OP scheme, with 60:40 funding ratio between the Centre and State, has identified 246 of Telangana’s 563 rural mandals as viable zones for oil palm.

To facilitate this expansion, the government has roped in 14 private companies, each assigned a factory zone to ensure farmers aren’t left with unprocessed harvests. Hindustan Unilever is setting up a palm oil processing unit in Kamareddy district, while 12 acres in Incherla of Mulugu district have been earmarked for another unit. These initiatives are aimed at easing the burden on farmers who have started harvesting but do not have processing infrastructure within a 50-km radius.

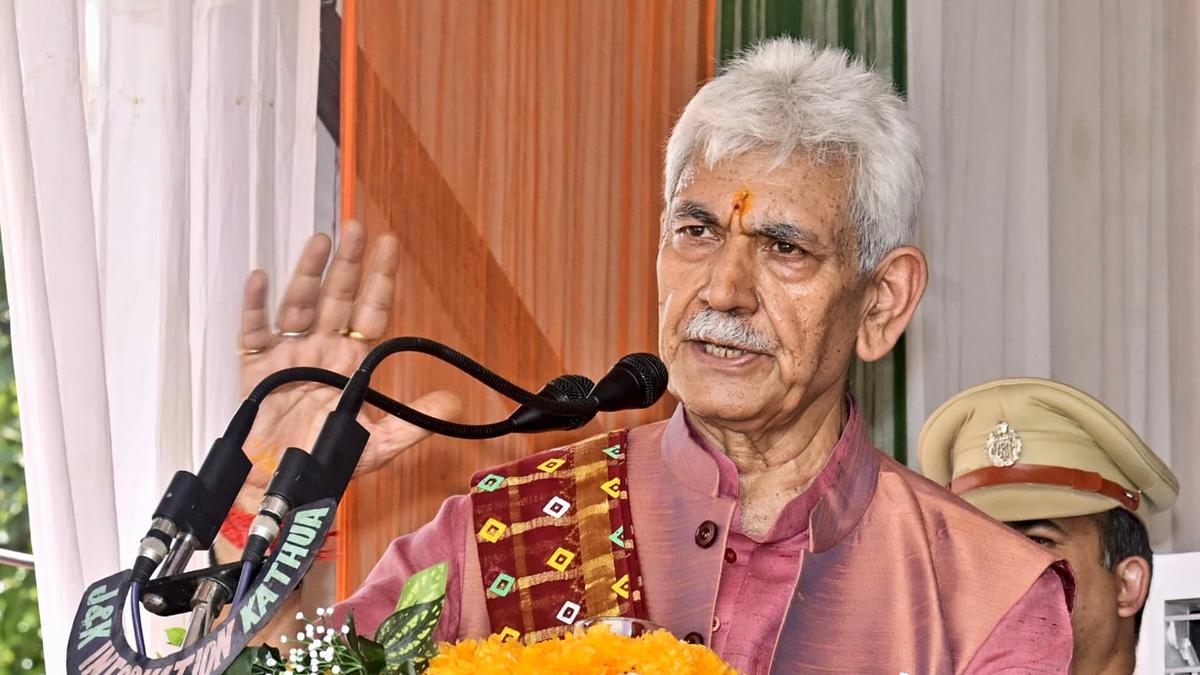

Farmer R. Gopal Reddy at his oil palm plantation in Aleru village of Nellikuduru mandal of Mahabubabad district.

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

So far, approximately 2.43 lakh acres are under oil palm in the State, with 1.97 lakh acres added under NMEO-OP between 2021 and 2024 alone. To make the transition attractive and viable, farmers are being offered subsidies of up to ₹50,918 per acre over four years. Of that, ₹22,518 goes toward drip irrigation in the very first year, an essential input for this water-intensive crop.

The momentum is strong, but the clock is ticking. The Agriculture Minister has urged officials in the Horticulture Department and partnering oil palm companies to accelerate efforts and ensure that the five lakh-acre mark is reached by the end of this financial year.

But there is a shadow of uncertainty. NMEO-OP, the backbone of the State’s oil palm push, is set to expire at the end of this fiscal. “We are hopeful it will be extended. If not, farmer enthusiasm may take a hit,” shares a senior official.

While the atmosphere is largely favourable, the road ahead is far from smooth. At the heart of the concern lies a recent policy shift: the Centre’s reduction of import duty on crude and refined palm oils — from 27.5% to 16.5% in May — has sent ripples of worry across the farming community. Many fear this move could depress the price of FFBs, which currently fetch about ₹20,000 per tonne, potentially cutting deeply into profits.

Bonthu Rambabu, district secretary of Telangana Rythu Sangham in Khammam, flags not only the volatile pricing but also the ageing of existing plantations and patchy returns as key issues that could undermine long-term farmer confidence.

According to Rambabu, the onus is now on government agencies and departments to step up, by ensuring timely supply of high-quality seedlings, expanding localised processing capacity and delivering consistent support to cultivators at the grassroots.

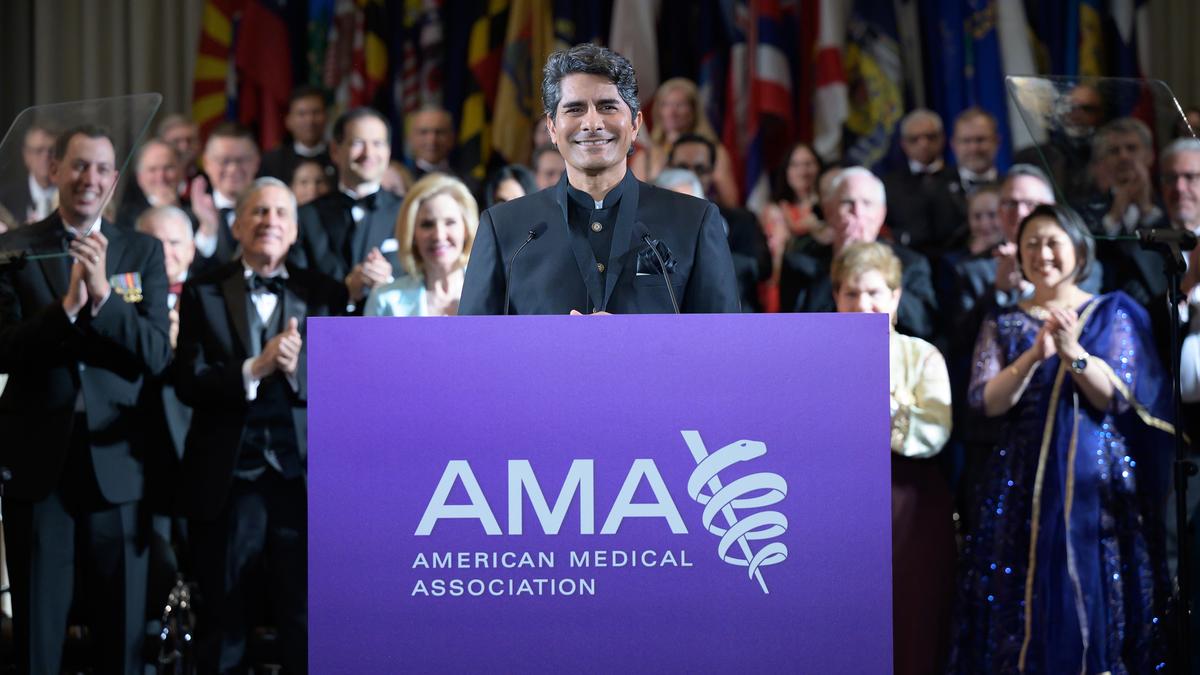

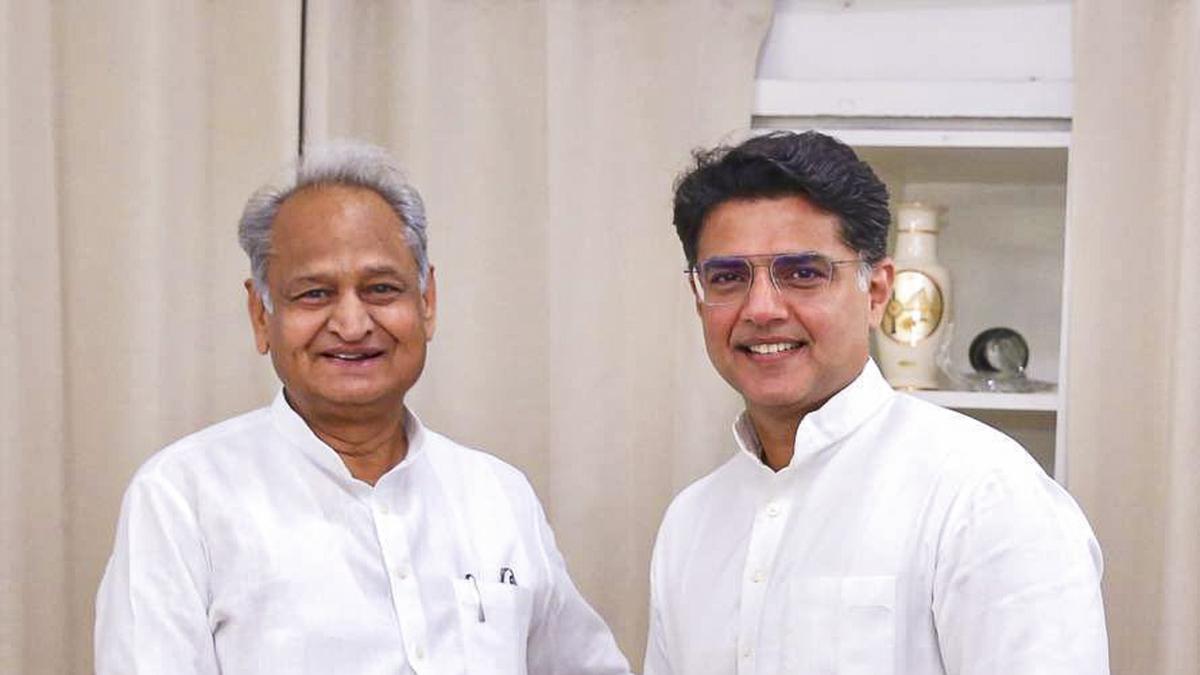

Echoing these concerns, Telangana Oil Palm Growers Association President Alapati Ramachandra Prasad says that Minister Nageshwara Rao had recently taken the matter to the national stage. In a meeting with Union Agriculture Minister Shivraj Singh Chouhan, he pushed for a fixed procurement price of ₹25,000 per metric tonne for FFBs — an ask that, if met, could safeguard farmer margins and morale.

In his representation, Nageshwara Rao also made a larger point that oil palm is not just another cash crop; it holds the key to self-reliance (achieving the objective of Atma Nirbhar Bharat) in edible oil production. With a high oil yield of 4-5 metric tonnes per acre and a perennial lifecycle, it offers unmatched productivity. But for it to fulfil that promise, farmers need more than just seeds and subsidies, they need assurance that their investment will pay off.

Price of oil palm ambition

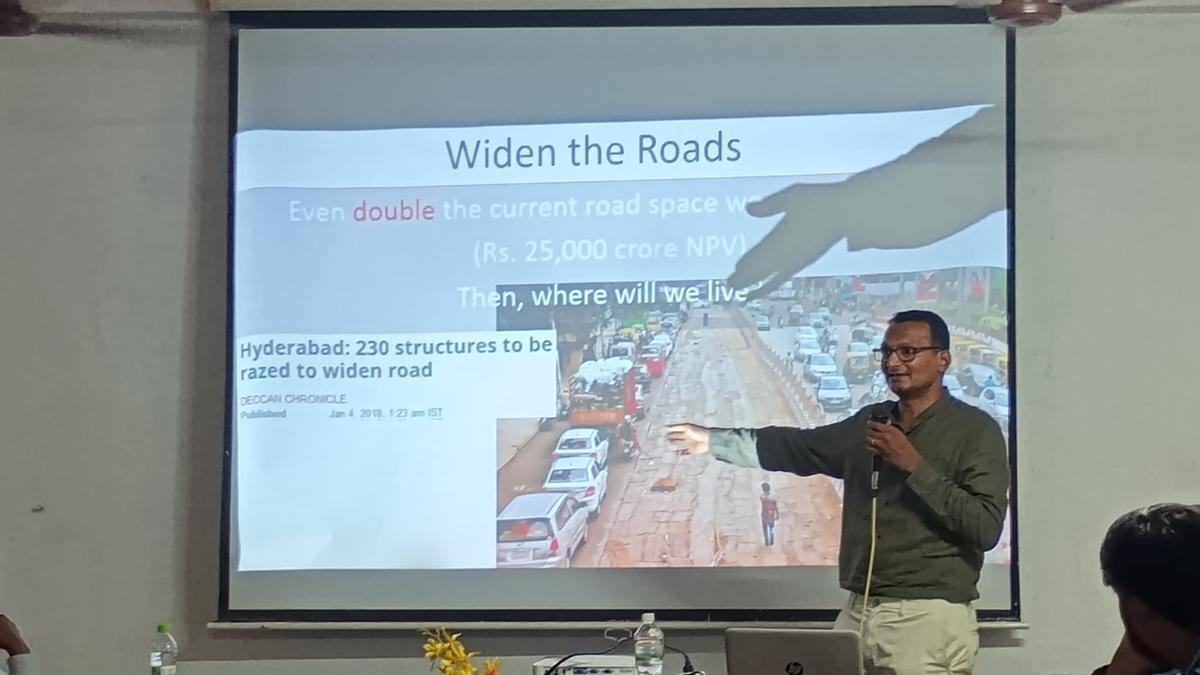

Yet, even as oil palm promises economic transformation, environmentalists and grassroots organisations are raising red flags. A mature oil palm, typically aged 8 to 10 years, requires approximately 250 litres of water per day in red soil and 150 litres per day in black soil. According to the Indian Institute of Oil Palm Research in Pedavegi (West Godavari), the recommended planting density is around 57 plants per acre.

In Telangana, where borewells remain the lifeline for irrigation, such water-intensive cultivation raises serious sustainability questions, especially during peak summer.

Farmer G.Srider Reddy (left) with his harvest.

| Photo Credit:

NAGARA GOPAL

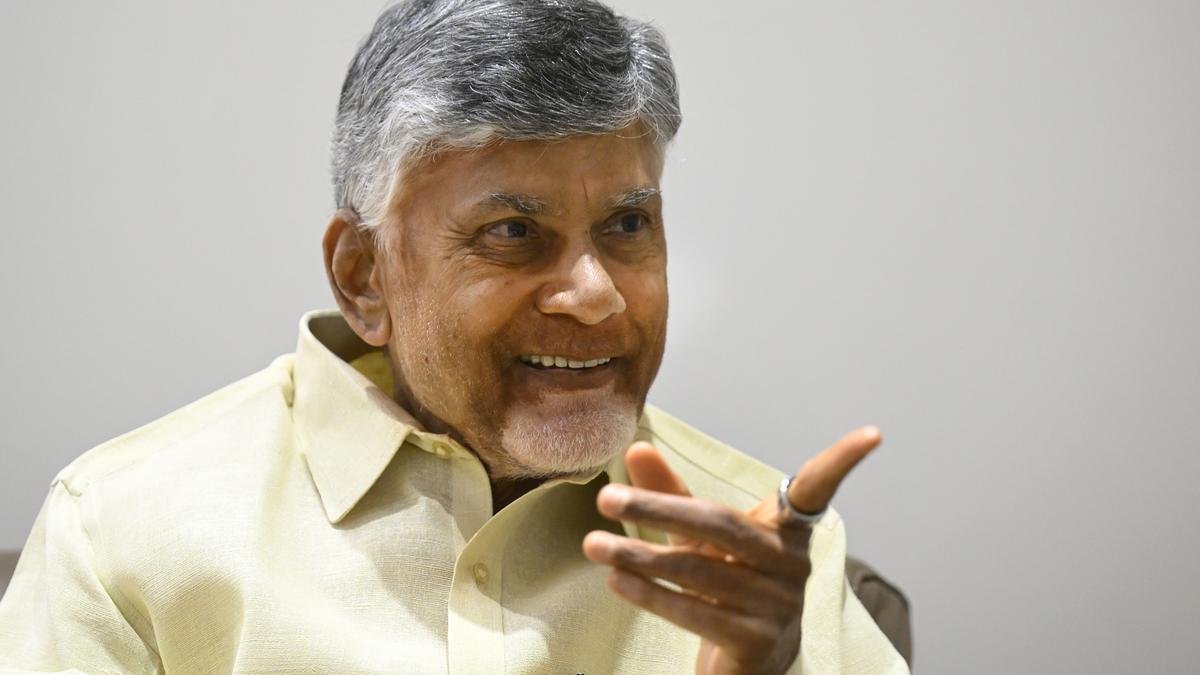

“Telangana is inherently dry. Pushing for a crop that thrives in humid, high-rainfall regions could prove ecologically disastrous,” says farmer leader Kanneganti Ravi, vice-president of Rythu Swarajya Vedika. He warns that aggressive oil palm expansion could degrade soil health, diminish biodiversity and push groundwater levels further into distress.

Ravi also questioned the wisdom of putting all of Telangana’s eggs in one oily basket. By focusing so heavily on oil palm, he argues, the State risks edging out diverse, possibly healthier and more resilient alternatives that could offer long-term sustainability.

India’s oil palm map is already lopsided. Andhra Pradesh, Telangana and Kerala together account for 98% of the country’s oil palm output. Telangana’s recent thrust, powered by policy and protected under the Oil Palm Act, 1993, is undoubtedly a bold leap toward redefining that dominance. But ambition must be balanced with ecological foresight.

The sapling once planted by N.T. Rama Rao has grown into something far more symbolic than a productive tree — it now represents a turning point in Telangana’s farming economics. For thousands of paddy-dependent farmers, oil palm holds the promise of higher, more stable returns. But success won’t be measured by yield alone. Market stability, processing infrastructure, responsible water management and a diversified cropping strategy will be just as critical.

For that, the government must act swiftly and decisively, with strong extension services, sustained subsidies and assured buyback mechanismsto ensure that oil palm doesn’t become a short-lived boom or an ecological bust.

Until then, the journey from a hopeful sapling to a truly sustainable plantation may still remain a slippery slope.

(With inputs from R.Ravikanth Reddy)

Published – June 13, 2025 09:17 am IST