- Recently, a tiger and her four cubs died in the Malai Mahadeshwara Hills Wildlife Sanctuary, evidence pointing to retaliatory poisoning in response to a case of cattle killing.

- Preliminary investigation reveals negligence by the forest department.

- Increased protection since the declaration of the wildlife sanctuary has led to a stable and increasing tiger population, but unchecked livestock grazing poses a major challenge.

- In the face of increasing human-wildlife conflict, conservationists call for efficient forest administration, greater protection and involvement of local communities.

The recent deaths of five tigers by alleged poisoning reveals gaps in wildlife protection and the challenges of conserving forests traversed by people and livestock.

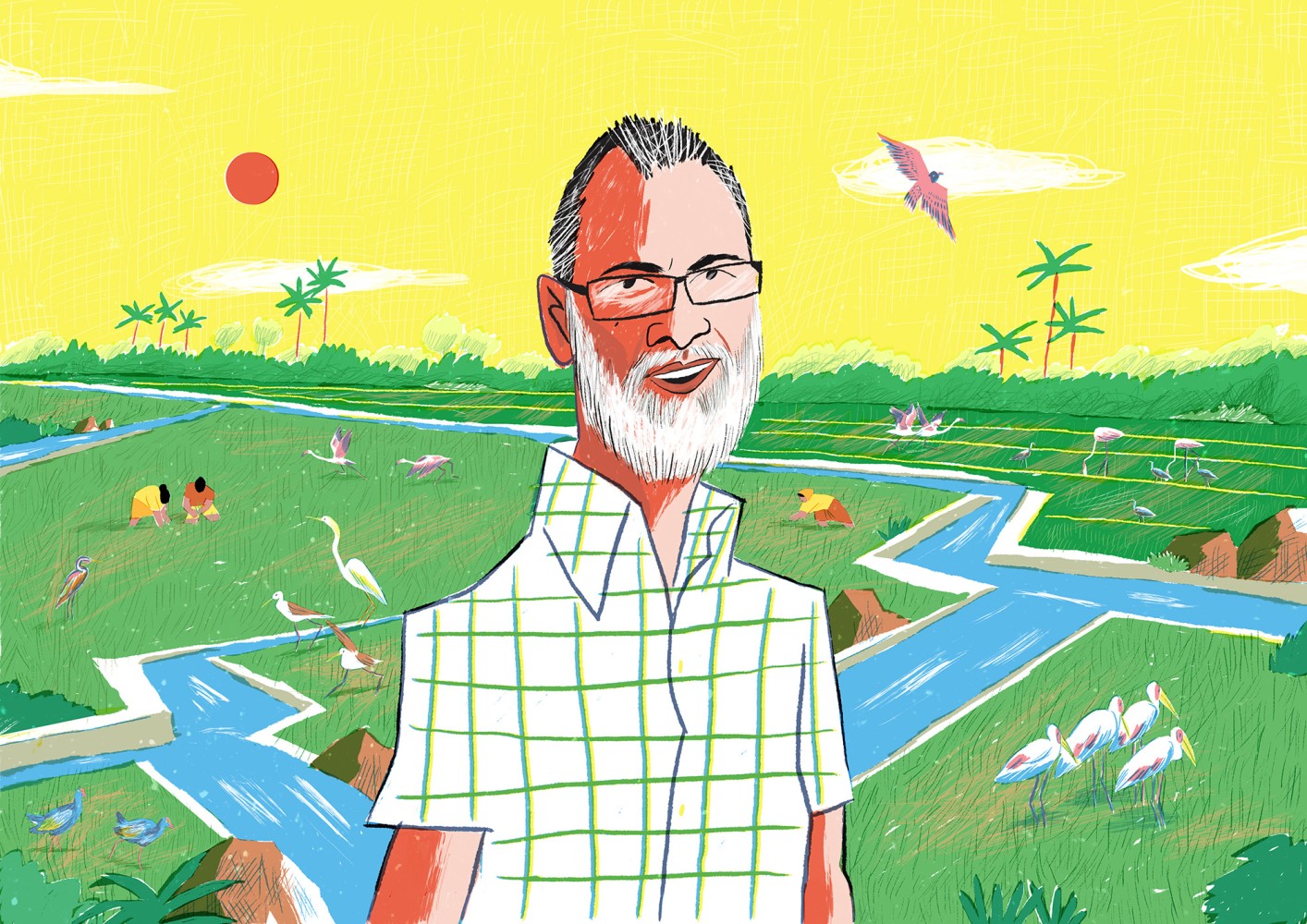

On June 26, an adult tiger and her four cubs were found dead in the Malai Mahadeshwara (MM) Hills Wildlife Sanctuary in Karnataka, prompting investigations. Three people were arrested on the accusation of lacing the carcass of their cattle with poison to target the carnivore that killed it. A preliminary report by an inquiry committee confirms the poisoning, pointing to dereliction of duty by forest officials and raises the issue of cattle grazing within the sanctuary. As details emerge, the incident has brought to light systemic issues with wildlife protection in a unique landscape where conservation challenges have evolved over time.

Why, what, and who

The Karnataka Forest Department faced a crisis on June 26, when five tigers were found dead in the Hoogyam range near the southern boundary of the MM Hills Wildlife Sanctuary. Reports confirmed that a cow carcass was found close to the tigers, raising suspicions that the tigers may have been intentionally poisoned in response to a killing of livestock.

The Karnataka Forest Minister ordered an investigation by a six-member team consisting of senior forest officials, a veterinarian, and a wildlife biologist. The Centre formed a team of representatives from the National Tiger Conservation Authority and the Wildlife Crime Control Bureau for a parallel probe.

As more details emerged, negligence by forest officials came to the fore. The tiger carcasses were discovered two days after they had died, despite being less than a kilometre from an anti-poaching camp and very close to a road. Two days later, news broke of the arrest of three people who had allegedly admitted to poisoning the carcass of their cow to avenge its death. A week after the deaths made headlines, the state-level investigation team revealed its preliminary findings. It confirmed that the tigers had died after consuming a toxic chemical based on veterinary analysis and statements from the accused and ruled out poaching as the cause. Some news reports suggest that the poison may be the highly toxic insecticide carbofuran, though the final investigation report is awaited.

The preliminary inquiry report also highlighted systemic failures in the forest department. Several vacant positions for frontline personnel, including beat foresters and forest watchers, has led to a severe shortage of staff. Among those who are employed and carrying out challenging on-ground patrolling, none have received salaries for the last three months, revealing administrative apathy in the processing and disbursement of funds. Following the report, four forest officers, including the Deputy Conservator of Forests of the MM Hills Wildlife Sanctuary, were suspended.

“Had they [forest watchers] been paid, they would have been in the field and known about this tigress with cubs. They would have been on alert and more watchful,” says Joseph Hoover, a wildlife activist and former member of the Karnataka State Wildlife Board. “The person whose cow was killed may not have dared to come into the forest for grazing.”

A long view of protection

The MM Hills are an extension of an arc of contiguous tiger reserves at the heart of the Western Ghats landscape, boasting more than 800 tigers across forests of Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, and Kerala. The MM Hills Wildlife Sanctuary extends eastwards from BRT Tiger Reserve, skirting the Tamil Nadu state line; it lies wedged between the Sathyamangalam Tiger Reserve to its south-west and the Cauvery Wildlife Sanctuary to its north-east. These two sanctuaries are thought to be important sinks for tigers spilling over from the adjoining tiger reserves.

Before the MM Hills area was declared a wildlife sanctuary in 2013, less than a third of its area was protected. The region, a mosaic of scrub, savanna and deciduous forest crisscrossed by riverine habitats and evergreen patches on hill tops, harbours many endangered animals. Around 900 sq km of its area was brought into protection, with improvements to infrastructure and increases in the number of forest staff patrolling the area. Around the same time, the adjoining Cauvery Wildlife Sanctuary was also expanded considerably.

“It brought focus on wildlife conservation in the area, while this place was only known for granite quarrying and extraction in the past,” says wildlife biologist Sanjay Gubbi, who has been involved in conservation efforts in the landscape and is a part of the state investigation team. In the following years, news reports from the region documented confrontations between forest officials and poachers, arrests, and crackdowns on quarries and resorts around these sanctuaries.

During this period, a camera trap study by Gubbi’s team identified at least 11 adult tigers and three cubs in the MM Hills and Cauvery Wildlife Sanctuaries. Among these, a tigress with three cubs was spotted in the MM Hills Wildlife Sanctuary, offering evidence for a breeding individual and hope for a growing population. “The tiger numbers have remained stable with a marginal increase (12-15 individuals). Tigers are breeding and raising cubs within the MM Hills Wildlife Sanctuary, which is an excellent indicator of recovery,” says Gubbi.

Conservation challenges, old and new

The same study mapped the abundance of wild prey species and documented the widespread presence of livestock across the two sanctuaries. Competition for shared food sources with livestock can lead to declines of wild herbivores, many of which form the prey base of carnivores. It can also lead to the transmission of disease from domestic to wild animals. A recent study in the MM Hills using environmental DNA revealed that over a third of the plants eaten by domestic cattle are also food sources for wild herbivores, with a 68% overlap in the diets of cattle and sambar deer.

“Before it was declared a wildlife sanctuary, local people used to take a lot of cattle for grazing and had cattle camps inside the forest,” says Sidappa Setty, from the Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and Environment, Bengaluru, who studies resource use and conservation in this landscape. “There are two indigenous communities within the MM Hills Wildlife Sanctuary, the Soligas and Lingayats, who vary in their dependence on non-timber forest produce. Outside [the sanctuary], there are many more non-indigenous communities who take their cattle for grazing to the forest,” he says.

A senior forest officer familiar with the landscape explains that there were over two dozen cattle pens along the riverbanks in the past, each with hundreds of cattle that grazed in the forest before these camps were banned over a decade ago. However, in recent years, there has been an increase in grazing pressure from large numbers of cattle that are not owned by local communities but brought into graze in the forest from neighbouring regions.

“Though livestock losses are frequent, herders do not report these to authorities,” says Gubbi. The preliminary investigation into the tiger deaths in MM Hills recommends a complete ban on grazing by “non-local cattle” and a review of grazing rights. However, areas in the forest that historically served as livestock grazing sites for cattle owned by local communities have been overrun by the invasive shrub Lantana camara. Studies have found that facing alternatives of migration or purchasing expensive fodder, herders are walking farther into the forest in their search for grazing sites.

Human-animal conflict in the landscape

In recent years, the numbers of human-wildlife conflict have increased in the Chamarajanagar circle, which administers the BRT Tiger Reserve and MM and Cauvery Wildlife Sanctuaries. The number of compensated cattle kills in this circle have increased from 268 to 406 in 2023-2024, according to Karnataka Forest Department data. Last year, more than half of the 406 cattle kills occurred in the Cauvery Wildlife Sanctuary, while 37 took place in the neighbouring MM Hills. Of the 14 human deaths in Chamarajanagar circle last year, eight incidents occurred in the BRT Tiger Reserve, and three each in MM Hills and Cauvery Wildlife Sanctuaries. Crop raiding by elephants has also been a major concern.

Since 2021, there have been 67 tiger deaths in Karnataka, 46 of which have been within tiger reserves, according to data from the National Tiger Conservation Authority. Two of these involved the seizure of poached tiger parts, while the rest were attributed to either natural deaths, or unnatural deaths not related to poaching. Across India’s tiger reserves, close to a third of tiger mortality cases from 2012-2014 are pending (96 pending cases in 2023 and 85 in 2024), which leave the underlying causes unresolved.

The only tiger deaths reported from MM Hills Wildlife Sanctuary in the last five years were the recent deaths attributed to retaliatory killing. Gubbi says that they first spotted the adult tiger in camera trap images over a decade ago. “We have documented her with multiple litters and consistently with four young cubs. She has been a very productive individual,” he adds. Among the four cubs that died, three were females. “Their contribution to the tiger recovery of the landscape would have been huge, and that is the larger loss,” Gubbi says.

The way forward

In the aftermath of this blow to tiger conservation, calls for addressing gaping issues with forest administration and tightening protection are being made. Talks of reviving the proposal to notify the MM Hills Wildlife Sanctuary as a tiger reserve, which was accepted by the NTCA in 2021 but shelved by the state, are also ongoing. “Once it is a tiger reserve, protection improves and also spills over to adjacent areas,” says Hoover.

“They [the forest department] need to immediately hire people and fill up vacancies,” he stresses. He adds that higher officials in the forest department must be held accountable for administrative failures such as unfilled positions and delays in payment of salaries to the frontline staff.

“Disbursals of compensation [in cases of conflict] are better now but need to be improved further and more compensation needs to be given,” says Malleshappa, a former State Wildlife Board member who is involved in conservation around the BRT Tiger Reserve. “We should take into consideration people who are inside and on the fringes of the forest. It is not possible for the forest department to protect the forest without the support of local people. Everybody should be sensitised,” he emphasises.

Read more: Tiger death highlights strained human-wildlife interactions

Banner image: The recent deaths of a female tiger and her four cubs in the Malai Mahadeshwara Wildlife Sanctuary comes as a blow to tiger conservation. It reveals lapses in forest protection, unchecked livestock grazing, and brewing human-animal conflict in the landscape. Representative image of tiger cubs by Gurdeep Singh via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).