- Since nearly two decades, 50 villages and hamlets in Rajasthan are suffering from the impacts of the polluted Jojari river.

- Experts say that the untreated chemicals from the steel and textile industries that flow into the river, affect the health of people, especially women. The same unsafe water is used for farming too.

- The National Green Tribunal has asked the government to prepare an action plan for the conservation of the river. A budget has been allocated for constructing sewage treatment plants, but challenges remain.

Thirty-year-old Dhanni Devi moved to Doli-Rajguro, a village located about 60 kilometres from Jodhpur, Rajasthan, a decade after her marriage. Since then, she has not been able to escape the chemical-laden, foul-smelling waters of the Jojari river. A mother of two, she has been deeply affected by this water. The polluted river adversely impacts not only the health of her children and family, but hers too, as a woman.

“Despite installing the mosquito net, both the children are bitten by big mosquitoes at night. When they cry, I have to hold them in my lap. I am unable to sleep properly. I have become so weak that my head and legs ache. I feel dizzy. I am taking multi-vitamins,” says Dhanni Devi, while adjusting her veil.

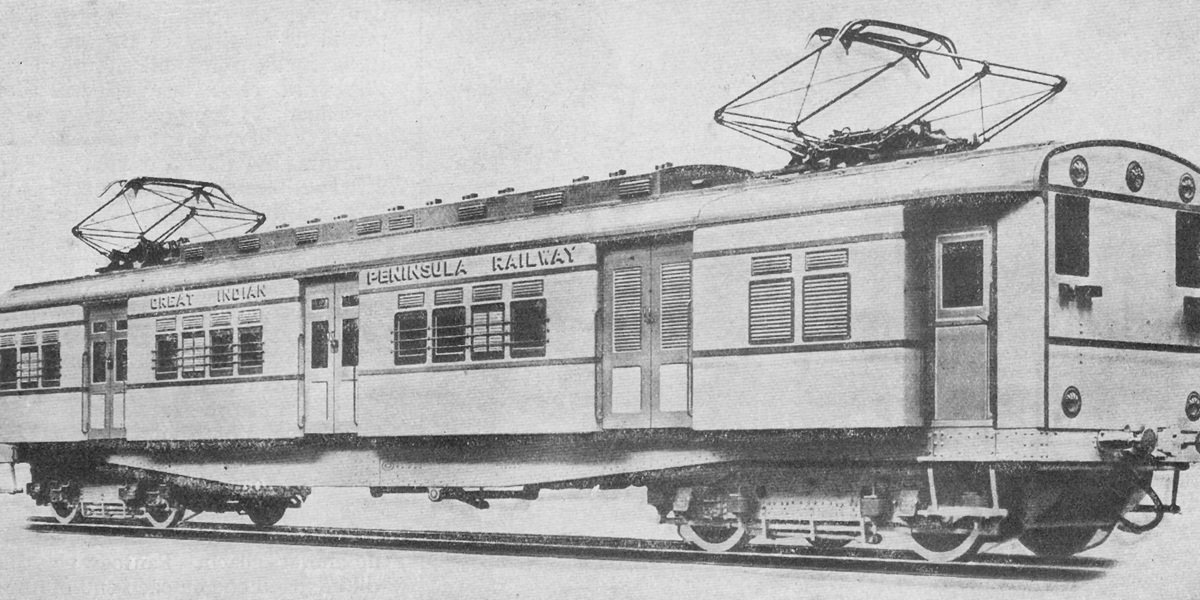

Jojari — a seasonal river — originates in Pandalu village of Nagaur and joins the Luni river in Balotra. When it flows through the limits of Jodhpur, the polluted water filled with chemicals from the textile and steel industries of Jodhpur flows into it.

About 50 villages and hamlets along the 100 km stretch of the Jodhpur-Barmer highway, including Doli-Rajguro, have been suffering from the side effects of the pollutants of the Jojari river since 2007, which is spread across a three-kilometre area.

Impacts on human health and livelihoods

According to Union Minister and Jodhpur’s Member of Parliament Gajendra Singh Shekhawat, about 16 lakh (1.6 million) people are impacted by the river.

“I am not able to eat anything after evening because of the foul smell all around. This is also making me weak,” shares Dhanni Devi.

Mohan Lal, a resident of the nearby Doli Kalan village, tells Mongabay India, “Pregnant women have to be taken to the doctor every other day. Either the pregnancy does not last or women have to be sent to a better location to save the newborn.”

Dhanni Devi’s neighbour Mirga Devi tells Mongabay India that water accumulates in the village as there is no provision for the river to flow beyond. The entire village is flooded with polluted water during monsoons. Residents do not get regular water supply in the village, and spend ₹1,200-1,500 to get tankers. Heera Devi of Doli-Rajguro says that the situation is so severe that even their storage tanks are filled with polluted water.

Shravan Patel, a wildlife conservationist in the area and a resident of Melba village, tells Mongabay India, “In every house, you will find someone suffering from some disease. Initially, there were more malaria patients here. Now, the climate of the area has changed from dry to acidic humidity and this is rotting our lungs.”

Commenting on this alarming situation, Sangeeta Lunkad, the dean of Faculty of Science at Jai Narayan Vyas University, Jodhpur, says that chemicals such as nickel, chromium, copper and iron from the steel industry and dyes from the textile industry, along with other chemicals, have been detected in the waters of the Jojari.

Gynaecologist Veena Acharya, the chairperson of the Indian College of Maternal and Child Health says, “Lead, cadmium and sulphur compounds have been found in the Jojari river. Lead enters the foetus through the umbilical cord, causing impaired brain development, low birth weight and neurological disorders. Cadmium affects the ability of the placenta and reduces the nutrients available to the foetus, which hinders physical development. On the other hand, high amounts of sulphur compounds can make water toxic and indirectly affect the overall health of women.”

Polluted water and farming

The waters of the Jojari also enter farms. Dhanni Devi’s father-in-law, Ghevar Ram, says, “My 20-bigha farm is submerged in dirty water. Now, we have to buy millet and eat it. The situation is the same in the entire village.”

Most of Ukaram Patel’s farms in Dhawa village are located next to the Jojari. When this correspondent reached the culvert built on this river in the month of May, it was difficult to stand there because of the foul smell. Black water was flowing in the Jojari below.

Ukaram Patel tells Mongabay India, “I have been forced to sow jowar for fodder. When the river overflows (due to siltation), dirty water spreads into the fields.”

In this area of the Thar desert, farming is done only during the rainy season. However, traditional crops such as millet and moong cannot be sown during this time as rainwater enters the fields through the river. Ukaram Patel says, “The issue has become more severe in the last eight to ten years. Out of 50 bighas, farming has completely stopped in 40 bighas.”

Ramesh Bishnoi, who lives in the neighbouring Dolikalan village, has 50 bighas of land submerged in dirty water. Now he works as a sharecropper in other villages. He says, “The problem has become worse due to stagnant water.”

Dimaram Bishnoi, former village head (sarpanch) representative and a resident of Dolikalan, says, “About 60% of the land in Doli Kalan, 99% of the land in Rajguro gram Panchayat and 70% of the land in Doli Khurd has been damaged. Doli and Rajguro gram panchayats are the most affected. We keep highlighting our problems, but no one has any solution.”

Shravan Patel says, “Four years ago, dirty water entered my field as well. When the water level reduced, I sowed mustard in eight bighas. In the first year, I got 20 sacks of mustard. Last year, the yield reduced to just one-fourth. I think that mustard has more chemicals than oil.”

According to a report by the Rajasthan State Pollution Control Board, “Farmers use the water of Jojari river for farming. Consumption of such agricultural products can have adverse effects on the human body as toxic heavy metals are present in the wastewater.”

Apart from the pH value, the total suspended solids, chemical oxygen demand, biochemical oxygen demand, and oil and grease quantities in the samples taken from Jojari were also found to be much higher than the prescribed standards, the report notes.

“The land around Jojari river is turning barren. One of my students brought a sample of onion leaves from there. When I dried them in the microwave, the whole house smelled of chemicals,” says Sangeeta Lunkad.

People are migrating from many villages, forced out by the impacts of the river’s pollutants. Rakesh Dewasi, who lives in Doli-Rajguro, says that his house in this village has been closed for 14 years. However, since the last five years, polluted waters are encroaching upon his new house too, which he built one kilometre away from the old one. “Our biggest issue is that there is water all around, but there is not even a drop of clean water to drink,” he says.

The waters of Jojari are also engulfing new areas. Dimaram says that wherever there is a way, the water flows there. Shravan Patel says that when there is a lot of water in the river during rains, it is entering new villages.

Declining biodiversity

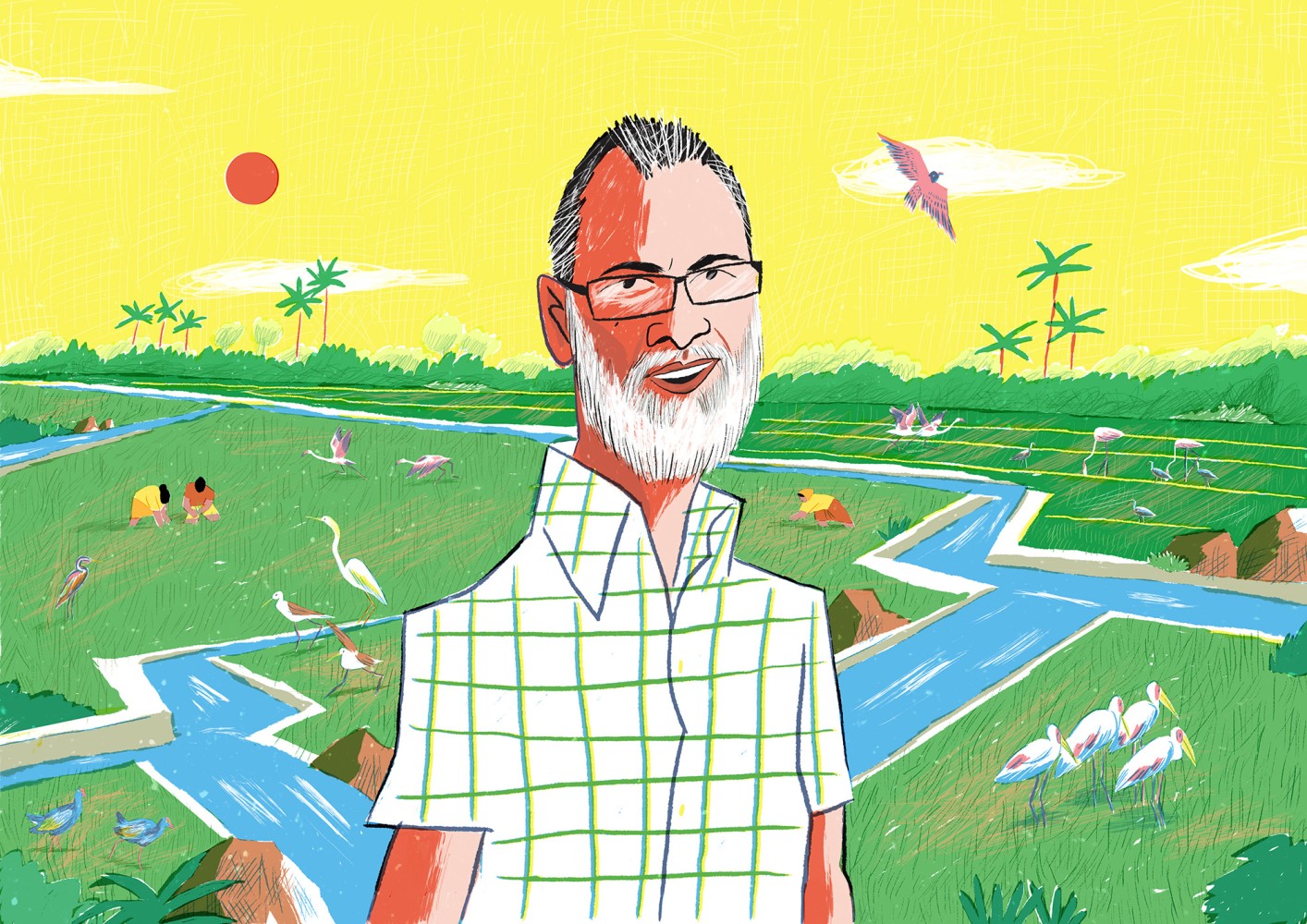

The Dhawa-Doli area outside Jodhpur, once supported wildlife and desert vegetation. Local trees like khejri, ker and the state flower rohida were found in abundance here. The area was populated by blackbucks, chinkara and migratory birds.

With the increasing pollution of the Jojari, flora and fauna started disappearing. When Mongabay India visited Rajguro, many nilgai were found drinking the polluted water.

Shravan Patel says, “When the water was clean, there were about a hundred trees of rohida in each field. Today you will find very few. Rohida is so sensitive that it dries up within a month of the arrival of poisonous water.”

According to a study conducted in 2021, a total of 49 species of plants were recorded on the banks of Luni, Bandi (which joins Luni from Pali) and Jojari rivers. Of these, the least number of plants were seen on the banks of Jojari.

G. Singh, who was part of the research and is the former head of forest ecology and climate change at the Arid Forest Research Institute, tells Mongabay India, “Due to pollution, the diversity of traditional vegetation around the river is decreasing and saltwater vegetation is increasing. Pollutants from the water are getting into the vegetation and reaching the bodies of wildlife. The stagnant water for most of the time can increase the threat to traditional vegetation. Rohida can be more affected than faras and khejri in the submerged state.”

The status of blackbucks is similar. Shravan Patel recalls a time in his childhood when blackbucks used to come in herds of about 300, but today their herd has reduced to just 30. Citing research by conservationist Asad Rehmani, he says that at that time there were about 3,700 blackbucks in Dhawa-Doli, while their number in Tal Chhapar was only 2,000. Now, Tal Chhapar sanctuary has 4,223 black bucks as per the 2021-22 census and the population in Dhawa-Doli has reduced.

Elaborating on the causes for the local extinction of the blackbuck, he says, “First, the fields were fenced. This stopped the free movement of wild animals. The number of dog attacks went up. Then from 2007-08, water containing chemicals started coming and the number of deer kept decreasing.”

Previously, wells and ponds were the only source of drinking water in this area. However, they have become polluted as well. Ramesh Bishnoi says that out of the six ponds in his village, four are filled with dirty water. There are two ponds that still have clean water, but they are very far.

A pressing need for solutions

A concrete solution has not been found yet to the pollution of the Jojari, which has been worsening for the last two decades. The residents of the villages in its vicinity are tired of protesting. They have met senior officials, but it has amounted to nothing.

The matter also reached the National Green Tribunal (NGT) and last year, the court asked the state government to prepare an action plan to stop pollution in the river. According to the data, 230 megalitres of domestic waste is generated in Jodhpur per day (MLD). Out of this, only 120 MLD is treated, while the remaining 110 MLD is dumped straight into the river. According to data from the Rajasthan Pollution Control Board, the amount of industrial waste being released is approximately 20 MLD; while the treatment plants can handle this quantity, only 11 MLD reaches them, with the rest ends up leaking or being washing away due to inefficient pipeline networks.

Jodhpur’s District Collector Gaurav Agarwal tells Mongabay India, “The central government has allotted a budget of ₹176 crore. Four Sewage Treatment Plant (STPs) will be built and the sewerage line will also be repaired. The construction work is going to start soon. The old 100 MLD plant in Salawas is being upgraded.”

There are 312 registered textile industries in Jodhpur and 94 steel re-rolling mills. There are also 13 other industries. On the other hand, there are about 2,100 industrial plots in the Jodhpur cluster of Rajasthan State Industrial Development and Investment Corporation Limited (RIICO).

A new pipeline part of the sewage network, set to be approximately 23.5 km long, is now being laid to ensure that wastewater reaches the treatment plan directly. The construction work for about 5.5 km of the line has been completed. Agarwal says, “The Common Effluent Treatment Plant of both the industries is built using old technology. The steel industry’s one is being upgraded, but the work of the textile industry is stuck due to lack of funds.”

Meanwhile, Sukharam Patel, the president of the Dhawa Market Association, suggests that if the river is deepened (by removing silt) and widened by 50 feet in the three-kilometre stretch between Lunawas and Doli, then 80% of the farms will not be submerged by polluted water.

Cleaning up the Jojari is a pressing need that must be acknowledged. During the monsoons, polluted waters from Jojari and Bandi reach the only major river of the desert and pollute it too — the Luni. Increasing pollution in the Luni spells disaster for farmers in the region, as it is a vital source of irrigation in the desert.

Read more: India’s polluted rivers are a global pollution problem

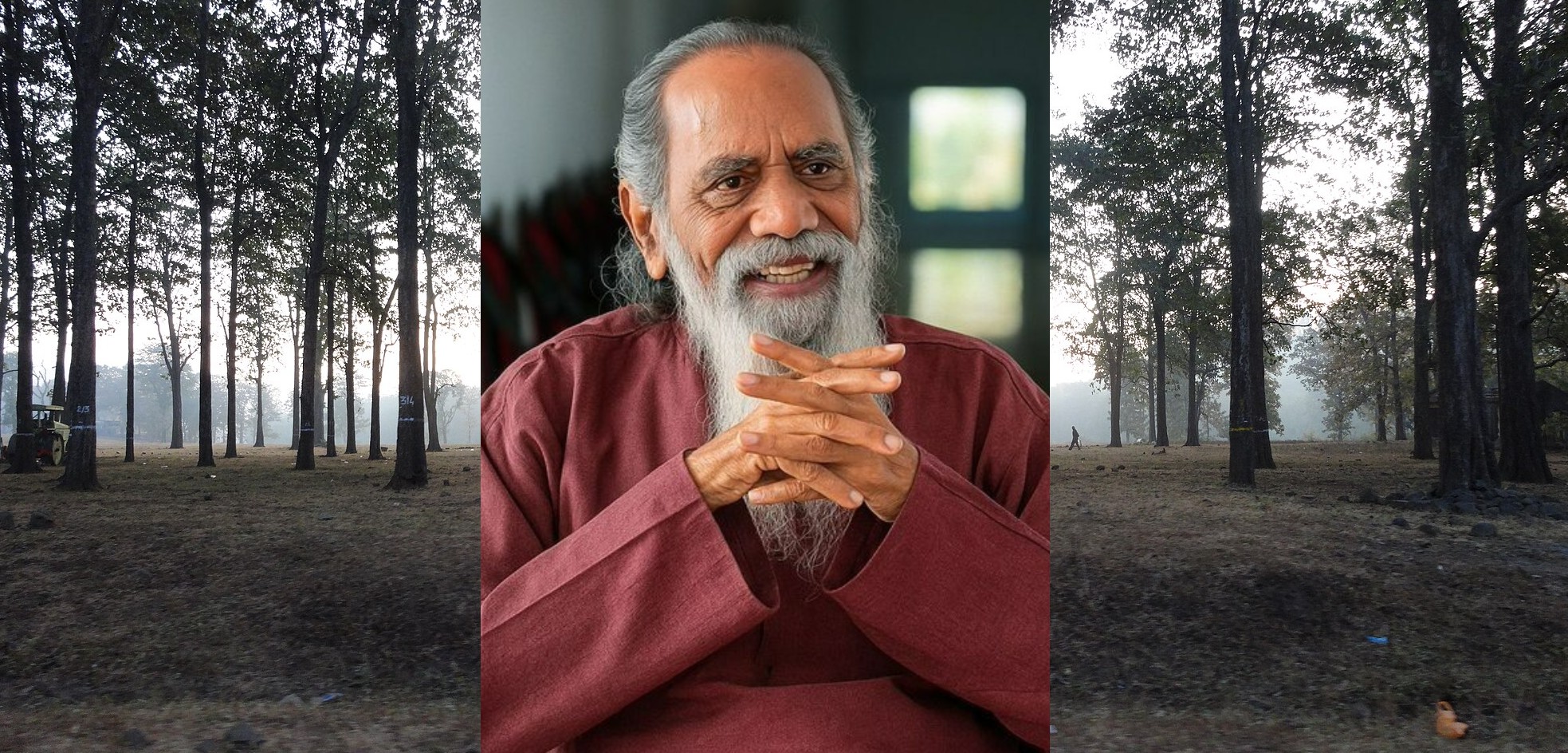

Banner image: About 50 villages and hamlets along the Jodhpur-Barmer highway have been suffering from the side effects of the pollutants of the Jojari river since 2007. Image by Nirmal Verma/Mongabay.