- Karnataka’s plan to rehabilitate over 100 tribal families in a 20-acre plot adjacent to the Brahmagiri Wildlife Sanctuary has sparked concern among environmentalists.

- Experts warn that establishing a human settlement requires large-scale tree felling and infrastructure development on a site that falls in the eco-sensitive zone.

- Resettling families, along with livestock and domestic dogs, in the area could increase human-wildlife conflict, spread diseases like rinderpest and canine distemper, and disrupt critical wildlife corridors.

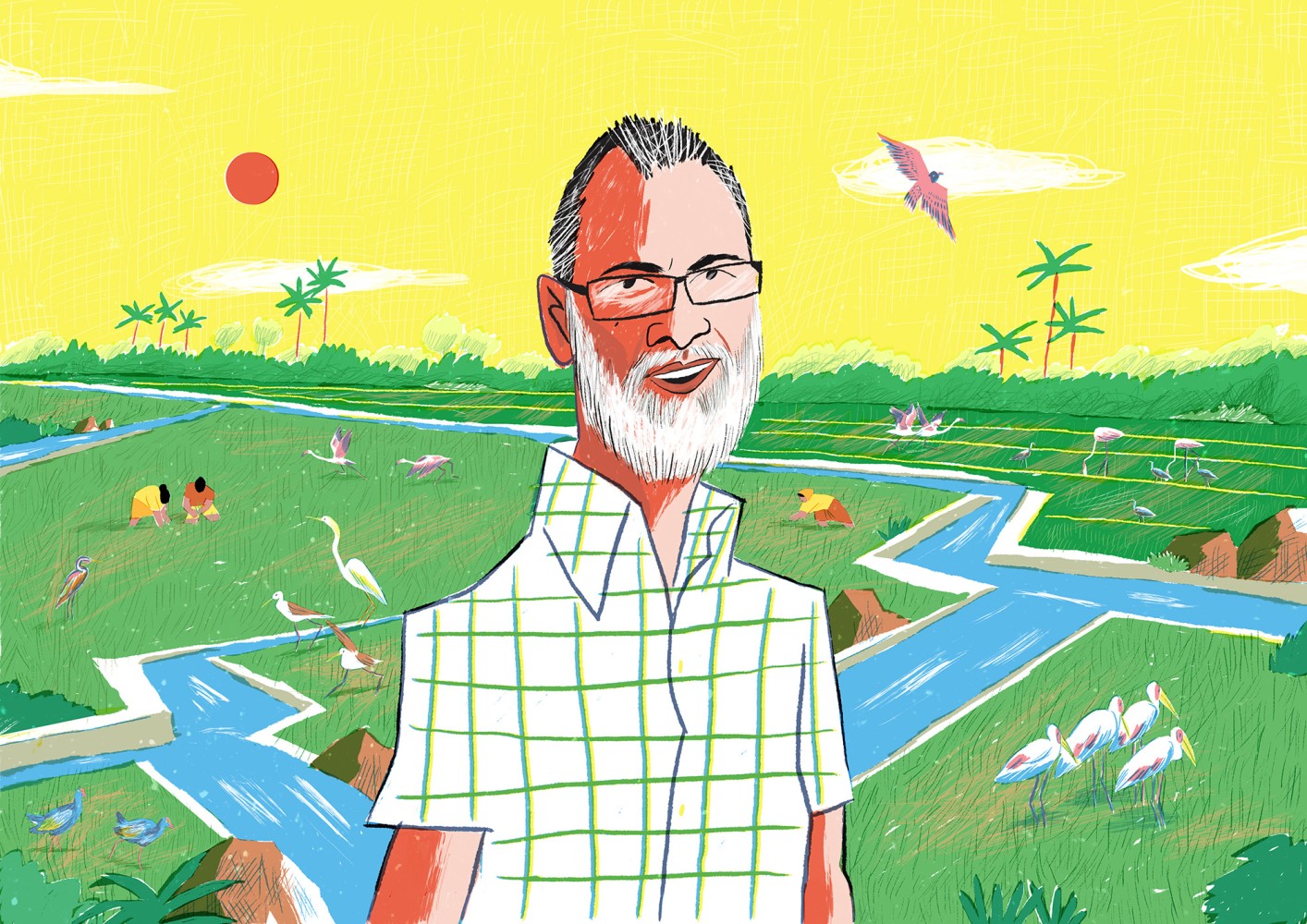

If the Karnataka government has its way, 20 acres of pristine land adjacent to the Brahmagiri Wildlife Sanctuary in Kodagu district will soon be converted into a large tribal colony to house more than 500 people — a decision that has wildlife activists and locals in a bind.

The land in question lies in Survey No. 147/2 at Theralu village in Virajpet taluk. This parcel of the revenue land borders the Brahmagiri Wildlife Sanctuary, where the Barapole river originates. It has been handed over to the Karmika Kalyana Ilake, or the Labour Welfare Department.

The decision to allocate the land was taken in 2017 by the then Deputy Commissioner, B.C. Satish, to resettle 100 landless tribal families belonging to the Kuruba and Yerava communities, most of whom were evicted from the Diddahalli forest in 2016. The process has gained momentum following a recent push from Kodagu MLA A.S. Ponnanna. Forest officials stationed near the site informed Mongabay India that they stopped a group of people from initiating land conversion work in June.

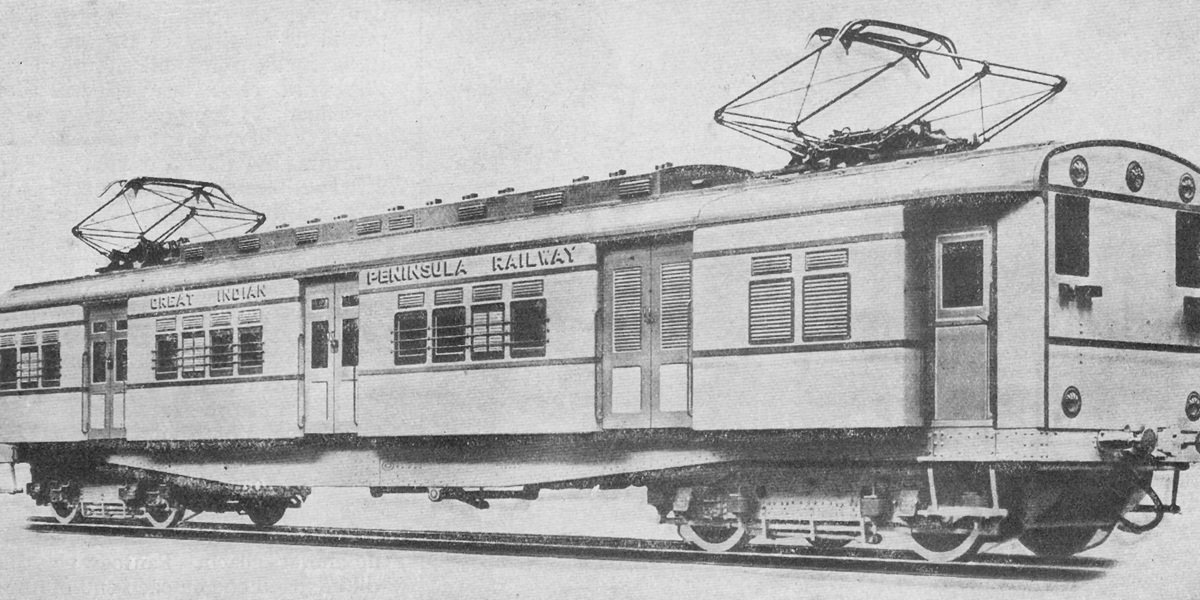

Brahmagiri Wildlife Sanctuary, notified in 1974 under the Wild Life (Protection) Act, covers 181.29 square kilometres in southern Kodagu district, Karnataka. Located in the core of the Western Ghats, the sanctuary features rugged terrain and receives high annual rainfall ranging from 2,500 to 6,000 mm. It harbours rich biodiversity with a high rate of endemism and is home to several critically endangered species.

Kodagu has witnessed land conversions in the past that have altered the human-wildlife interface, often leading to increased interactions between humans and wild animals. The construction of the Harangi dam in the 1980s and the subsequent resettlement of communities closer to forest areas is a case in point. Villages like Yadavanadu, located near the reservoir, have become the epicentres of human-elephant conflict which the local communities attribute to the dam construction and their displacement into wildlife habitats.

A corridor for wildlife movement

The sanctuary serves as a crucial corridor for large mammals like the tiger and Asiatic elephant, linking protected areas in Karnataka and Kerala. It is also part of the Mysore Elephant Reserve under Project Elephant. The area is ecologically significant due to its exceptional floral and faunal diversity.

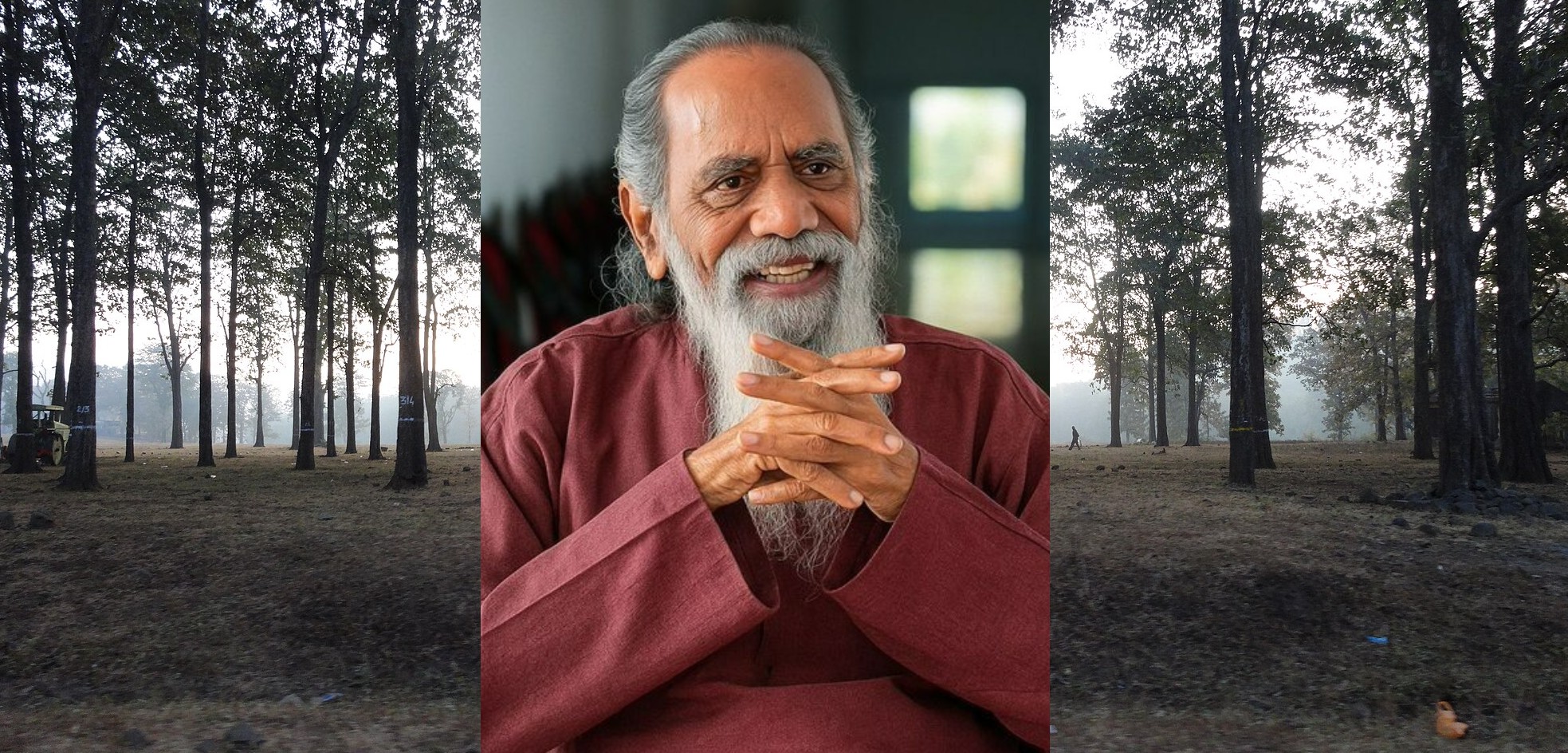

Environmentalists have raised serious concerns about the ecological impact of the proposed project. “The site falls within the eco-sensitive zone, as it is less than 500 metres from the Brahmagiri Wildlife Sanctuary, a legally protected area,” former honorary wildlife warden of Kodagu and president of Coorg Wildlife Society K.N. Bose Madappa, tells Mongabay India. While he expressed support for providing housing to tribal communities who rightfully deserve it, he questioned the suitability of the location.

Activities such as road widening, tree felling, and increased air and vehicular pollution are regulated under the Eco-Sensitive Zone (ESZ) guidelines issued by the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC). Moreover, the Brahmagiri Hills, where the Barapole river originates, makes the area ecologically fragile. Construction, sewage, and litter here could jeopardise water quality and affect downstream habitats. These concerns have also prompted resistance from the Forest Department.

Kodagu Deputy Commissioner Venkat Raja, however, maintains that since the land falls within the ESZ, no activities prohibited under the ESZ guidelines will be carried out in the area. “The environment is for everyone. We cannot abandon the needs of the tribals. At the same time, no rules or laws will be violated to accomplish that,” Raja affirms.

Tiger presence a cause of concern

Being close to a legally protected area and a 300-acre private reserve, the SAI Sanctuary, the land witnesses high wildlife activity, which is a cause of concern for wildlife experts. Cattle lifting by tigers is frequently reported from nearby villages. “Just last month, a tiger lifted a cow from nearby,” says Madappa. According to N.H. Jagannath, Deputy Conservator of Forests (DCF), Virajpet taluk, around 50-60 cattle kills are reported annually from the area.

Human settlements in such zones can increase the likelihood of human-wildlife conflict, warns wildlife researcher Thammiah Chekkera, coordinator of the human-elephant coexistence programme at the Humane World for Animals India Foundation. Jagannath adds that such settlements could lead to significant territorial issues, as the area lies within vital wildlife corridors. “Elephant movement is high here, and Kodagu is already dealing with numerous conflict cases, spending nearly ₹5 crore annually on compensation,” he says.

Moreover, the area is a biodiversity hotspot, supporting rare and vulnerable species like the Nilgiri marten and Nilgiri langur. Human presence, especially with livestock and domestic dogs, can severely impact wildlife through habitat degradation, disease transmission from domestic animals such as canine distemper, and increased poaching pressure. Chekkera refers to the case of a rinderpest outbreak that wiped out the gaur population in Bhadra Wildlife Sanctuary in the early 1990s. “It was spread from the cattle,” he says.

Madappa has identified alternative land parcels away from protected areas that are more suitable for resettlement. “Setting up a colony for over 500 people would require significant infrastructure such as roads, electricity, and water, and could cost more than ₹20 crores. It would also lead to large-scale felling of trees and disturbances near the forest,” he says. “We remain committed to inclusive development and tribal welfare, but not at the cost of ecological integrity.”

Read more: Experts conflicted over the hard decision to soft release problem jumbos

Banner image: Brahmagiri serves as a crucial corridor for elephants and tigers, raising concerns about human-wildlife conflict that could intensify if the tribal colony is established. The proposed land witnesses high wildlife activity and cattle lifting by tigers is frequently reported from nearby villages. Image by Bose Madappa.