- The Supreme Court struck down two government amnesties allowing ex-post facto environmental clearances, calling them illegal and harmful to the environment.

- Legal experts and practitioners say this judgment is unlike other Supreme Court judgments about ex-post facto environment clearances and will have far-reaching consequences.

- The environment ministry is considering filing a review petition against the judgment or amending the Environment Protection Act, 1986, to make provisions for dealing with projects that violate the EIA notification.

On May 16, a Supreme Court judgment struck down two amnesties issued by the Union Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change (MoEF&CC) for violators of the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) notification.

One amnesty was notified in 2017 and another in 2021, both drafted by the environment ministry to regularise projects that had started without prior environmental clearance (EC) or had extended beyond approved clearances. The court criticised the 2017 notification and the 2021 Office Memorandum (OM), declaring them illegal as they allowed authorities to grant ex-post facto environmental clearances — an action the court found contrary to law and harmful to the environment.

Commenting on the 2021 OM, the two-judge bench of Justice Abhay S. Oka and Justice Ujjal Bhuyan observed, “The 2021 OM talks about the concept of development. Can there be development at the cost of environment? Conservation of environment and its improvement is an essential part of the concept of development. Therefore, going out of the way by issuing such OMs to protect those who have caused harm to the environment has to be deprecated by the courts, which are under a constitutional and statutory mandate to uphold the fundamental right under Article 21 and to protect the environment. In fact, the courts should come down heavily on such attempts.” The court was equally critical of the 2017 amnesty, stating, “…what was sought to be done was to protect the project proponents who committed gross illegality by commencing construction or commencing operation or process without obtaining prior EC as provided in the EIA notification.”

The court directed the government not to issue any amnesty for violators of the EIA notification in the future. Environmentalists welcomed the judgment, while industry groups and companies expressed concern over its potential impact on business.

In late April, Mongabay India had reported that the Confederation of Real Estate Developers’ Associations of India (CREDAI), India’s oldest mining company, Tata Steel, and a real estate firm Goel Ganga Developers, had sought to intervene in the case, pushing to reinstate the 2021 amnesty and requesting legal directions in favour of violators.

New judgment breaks precedent

On the penultimate page of its 41-page judgment, the bench led by Justice Abhay S. Oka issued a direction that legal experts have described as significant.

“We restrain the Central Government from issuing circulars/orders/OMs/notifications providing for grant of ex post facto EC in any form or manner or for regularising the acts done in contravention of the EIA notification,” the court stated.

Multiple environmental law experts and practitioners told Mongabay India that this direction — along with the court’s order to scrap the 2017 and 2021 amnesties — leaves no scope for the government to shield violators. They said this has created legal consequences for violators, unlike at any other time in the past when one amnesty was replaced by another in a few years.

“The significance of the judgment is, first, that the court has seen that it’s not once, twice, but multiple times that the MoEF&CC has come out with these notifications allowing for amnesty and ex-post facto clearances,” said advocate Vanshdeep Dalmia, who represented the petitioner Vanashakti, a Mumbai-based nonprofit organisation, in the Supreme Court. “Therefore, most importantly, the court has, in a way, passed a mandamus restraining the government from coming out with similar notifications, similar circulars, similar amnesty schemes. So, this is important so that, tomorrow, a repeat can’t be done…”

Debadityo Sinha, who leads the climate and ecosystems team at the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy, a legal think tank, noted that previous judgments — such as Common Cause v. Union of India (2017) and Alembic Pharmaceuticals v. Rohit Prajapati (2020) — had also ruled ex-post facto clearances to specific projects as legally unsustainable.

However, the Vanashakti judgment differs in one key aspect. “In contrast, this latest judgment takes direct aim at the institutionalised practice enabled by the (MoEF&CC) through its 2017 notification and 2021 Office Memorandum, both of which sought to regularise environmental violations via retrospective clearances without using the word ‘ex post facto EC’ but attempting to do the same,” explained Sinha.

Big implications

The Supreme Court’s judgment striking down the 2017 and 2021 amnesties for environmental violations has far-reaching legal and commercial consequences for companies and infrastructure projects, as revealed by interviews with industry and government officials.

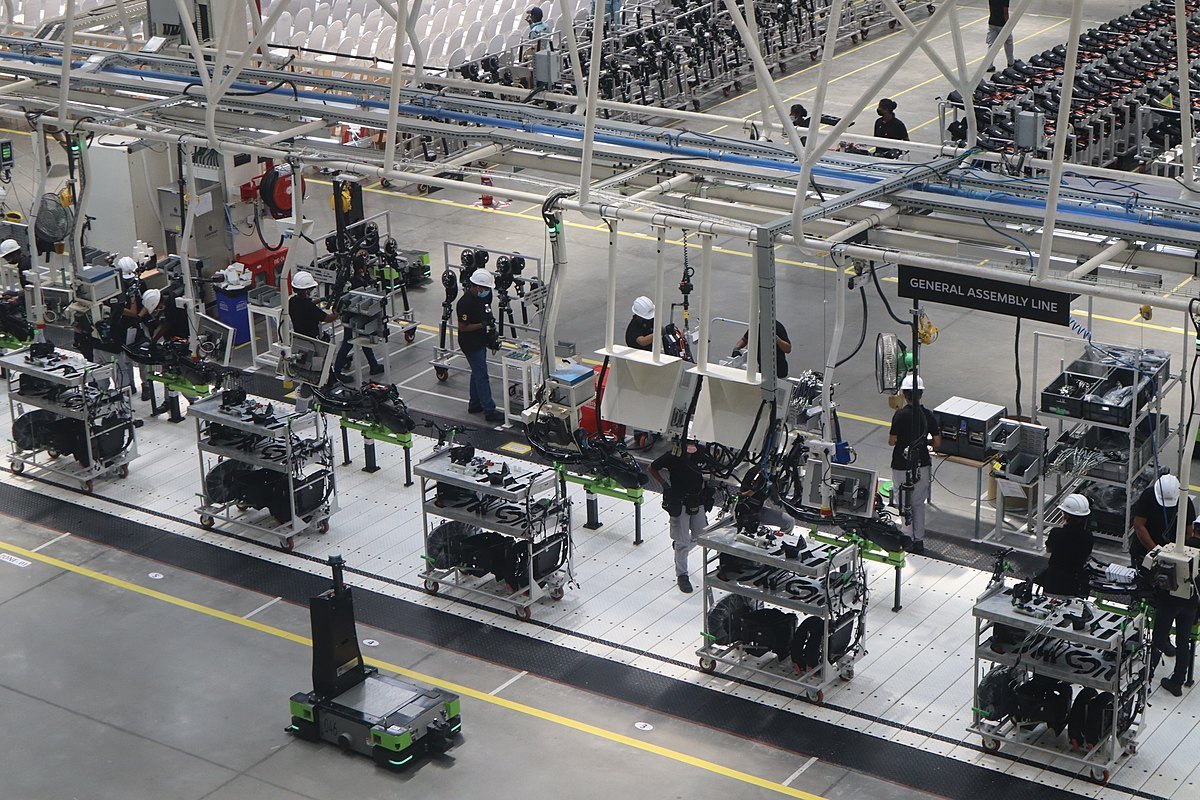

Take, for instance, the case of Kerala-based English Indian Clay Limited (EICL). According to its court submissions, the company operates “Asia’s largest mining and processing facility” with an installed capacity of 300,000 tonnes per annum, producing hydrous and calcined kaolin (China clay) — a raw material for the paper, pharmaceutical, cosmetic, and light-diffusing industries.

EICL submission in the Supreme Court, underlines that it had mined China clay without an environmental clearance and in violation of a mining plan it was committed to follow. The company was trying to get a clearance for its mining project in the Thiruvananthapuram district. The regulators in Kerala cited the Apex Court’s interim stay on the 2021 Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) to refuse its request for clearance. With both amnesties now struck down, the fate of its ₹180 million project in Thiruvananthapuram district, detailed in a 2021 pre-feasibility report, remains uncertain. EICL’s legal team declined to comment, but a lawyer involved in this case and still assisting one of the parties said the company is exploring legal options to restart operations. His contractual obligations prohibit him from making such details public.

A similar situation unfolded in Jharkhand, where Anjaneya Ispat Limited was operating a mini blast furnace at its Jamshedpur plant without the required environmental clearance. The company had initially applied under the 2017 amnesty and was later advised to apply under the 2021 version. However, the Supreme Court’s verdict has nullified both options. A source familiar with the case said the company is considering filing a review petition and exploring other legal avenues to regularise operations, which are currently suspended.

Even the state-run real estate giant, NBCC (India) Limited, appears to have been affected adversely by the Vanashakti case. According to an application the company filed in the Apex Court in September 2024, the top court’s interim stay granted in early 2024 on the 2021 amnesty, “restricted the State Level Environment Impact Assessment Authority, Kerala, from accepting penalty under the Office Memorandums dated 07.07.2021 and 28.01.2022 issued by the MoEF&CC and in the absence of the EC, the Applicant is not in position to obtain the consent to operate from Kerala State Pollution Control Board for the Project of Valley View Apartment, Ambalamedu, Karimugal P.O. Kochi, Kerala.” This is a prominent real estate project pursued by the state firm.

Beyond these three documented cases, a review of legal filings and interviews with representatives from industry bodies suggests that several other projects — especially in the real estate and mining sectors — are similarly affected by the ruling. According to its intervention application, real estate lobby group CREDAI had claimed that 99,300 ongoing real estate projects were “prejudiced” by the interim stay, the apex court has put on these amnesties. Now that the apex court has turned down any amnesty for violators, the future of these projects will also be uncertain.

B.K. Bhatia, Director General of the Federation of Indian Mining Industries, said the judgment could have wide-reaching economic effects. “The judgment will adversely impact the number of mines, particularly smaller mines, which will affect the economy and livelihood,” he said.

Systemic nature of violations

The Supreme Court was particularly critical of the environmental track record of the real estate and mining sectors. “The persons who acted without prior EC were not illiterate persons. They were companies, real estate developers, public sector undertakings, mining industries, etc. They were the persons who knowingly committed illegality. We, therefore, make it clear that hereafter, the Central Government shall not come out with a new version of the 2017 notification which provides for the grant of ex-post facto EC in any manner,” the court stated.

Environmentalists underscored the importance of this observation. “The Supreme Court’s observations indicate a deeply troubling pattern of deliberate non-compliance within the real estate and mining sectors. This highlights the systemic nature of violations in these industries, where regulatory processes are frequently bypassed or misused to facilitate unauthorised development and extractive activities and supported by the government,” said Debadityo Sinha of the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy.

However, representatives from both sectors voiced concern in their interviews with Mongabay India. “Our sector is badnaam [infamous] because of legacy issues, but that doesn’t mean it should be treated unfairly or like an outcast,” said a senior office bearer of a prominent real estate lobby group on the condition of anonymity as he is not authorised to speak to the media. “This judgment leaves no remedy for addressing violations, no matter how minor. It essentially means projects must shut down, stop operations, or face demolition. A one-size-fits-all approach is not a solution,” he added.

B.K. Bhatia argued that applications for ex-post facto clearances already under consideration should have been allowed to proceed. “Ex post facto applications which were under consideration by the ministry should have been permitted to be processed since the memos allowed these with penalties,” he said.

According to multiple officials in the MoEF&CC, the ministry is considering two legal options in response to the particular judgment. One involves filing a review petition before the Supreme Court against its judgment, and the other is amending the Environment Protection Act, 1986, to make explicit provisions for dealing with projects and companies that violate the EIA notification, which is issued under provisions of this law. While the review petition may not necessarily succeed in persuading the court to revisit its judgment and reinstate the amnesties, the amendment to the parent act may cause public controversy, said an official in the ministry, requesting anonymity as he is not authorised to speak to the media.

Read more: Industry pushes for reinstatement of amnesty for environmental violations

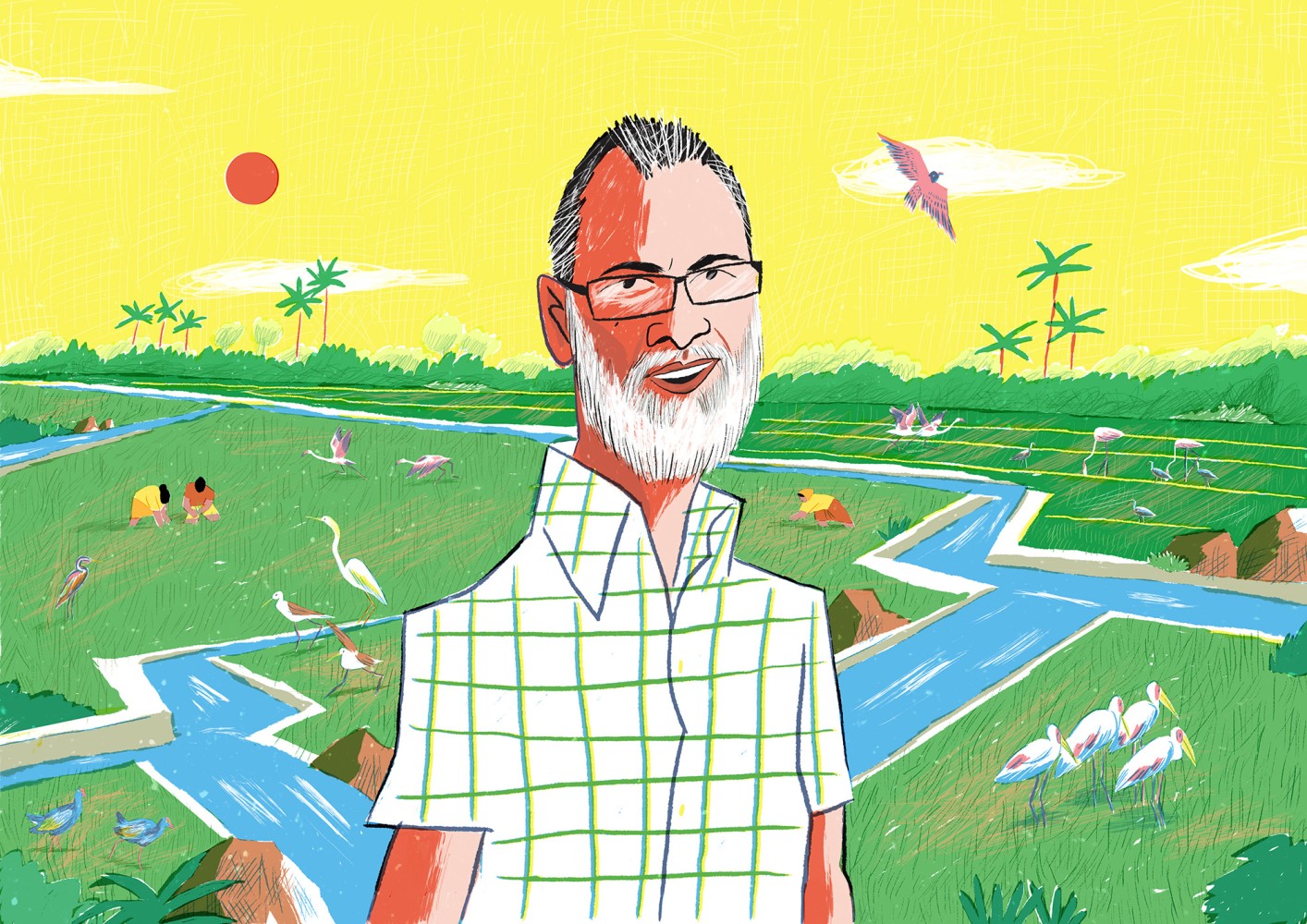

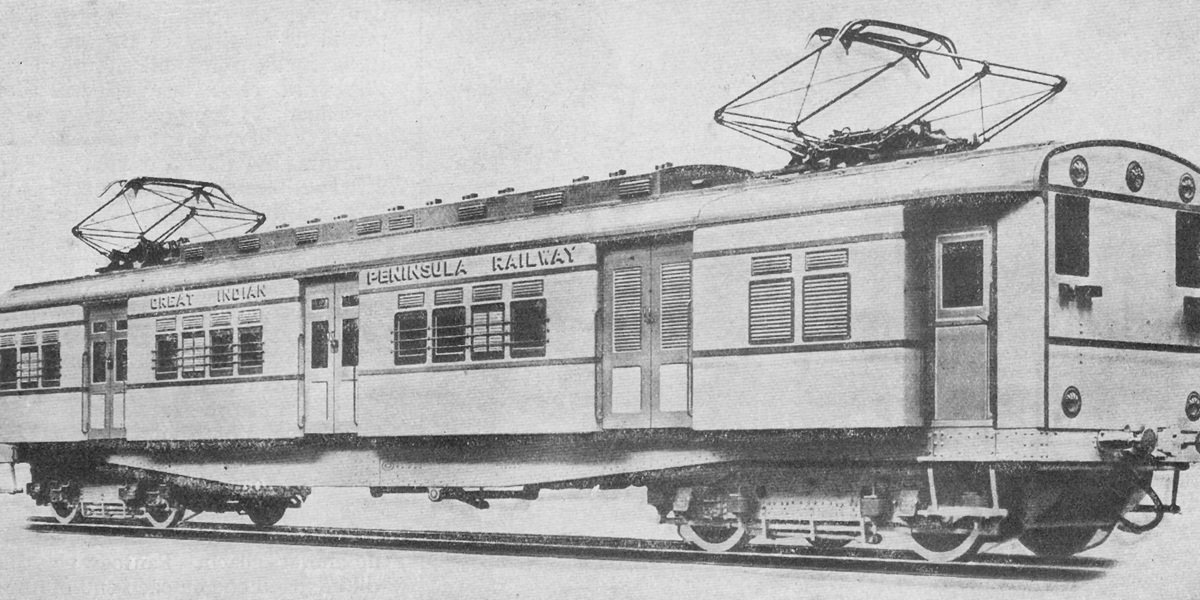

Banner image: Aerial view of sand mining. The Supreme Court’s verdict striking down the 2017 and 2021 amnesties for environmental violations has significant legal and commercial implications for companies and infrastructure projects. Image by Saiphani02 via Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-SA-4.0).