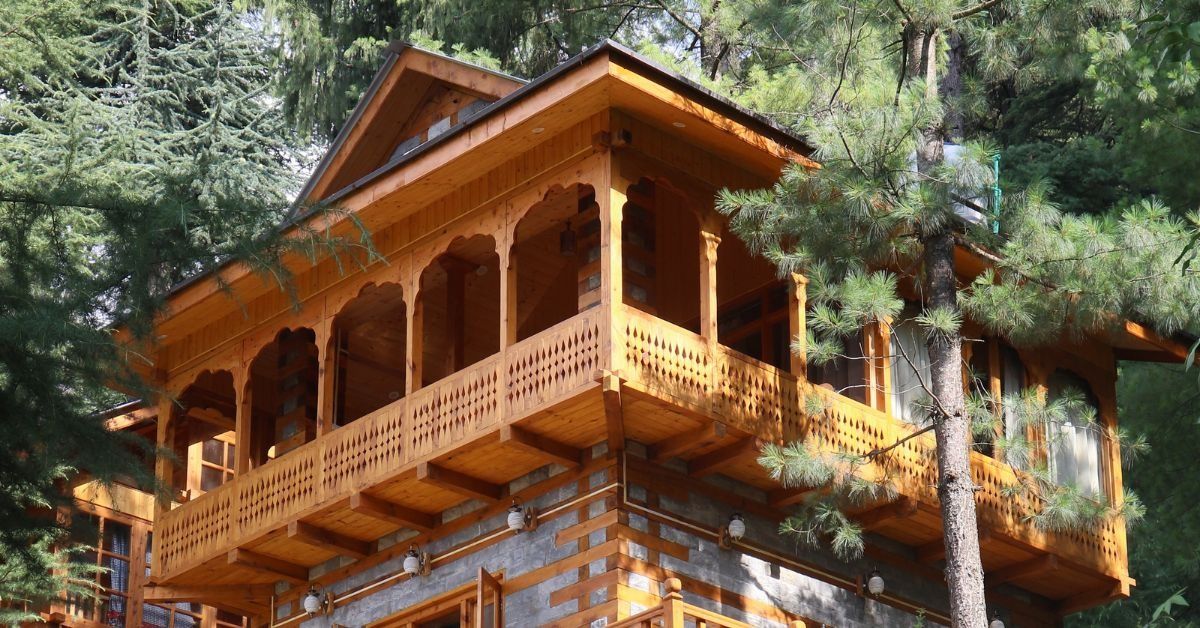

As successive cloudbursts, flash floods, and landslides battered Himachal Pradesh — claiming over 370 lives and damaging 6,300 houses, 461 shops, and factories — symbols of resilience stood tall in the form of homes built with kath kuni and dhajji dewari architecture.

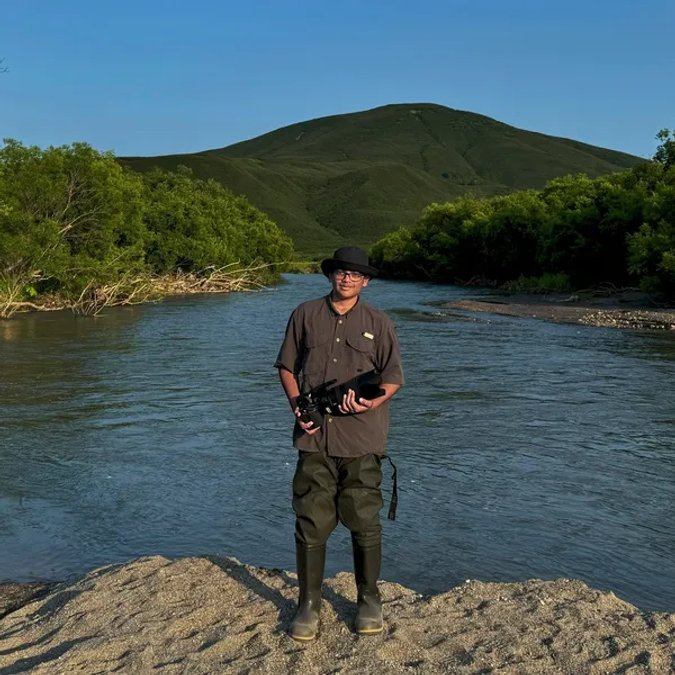

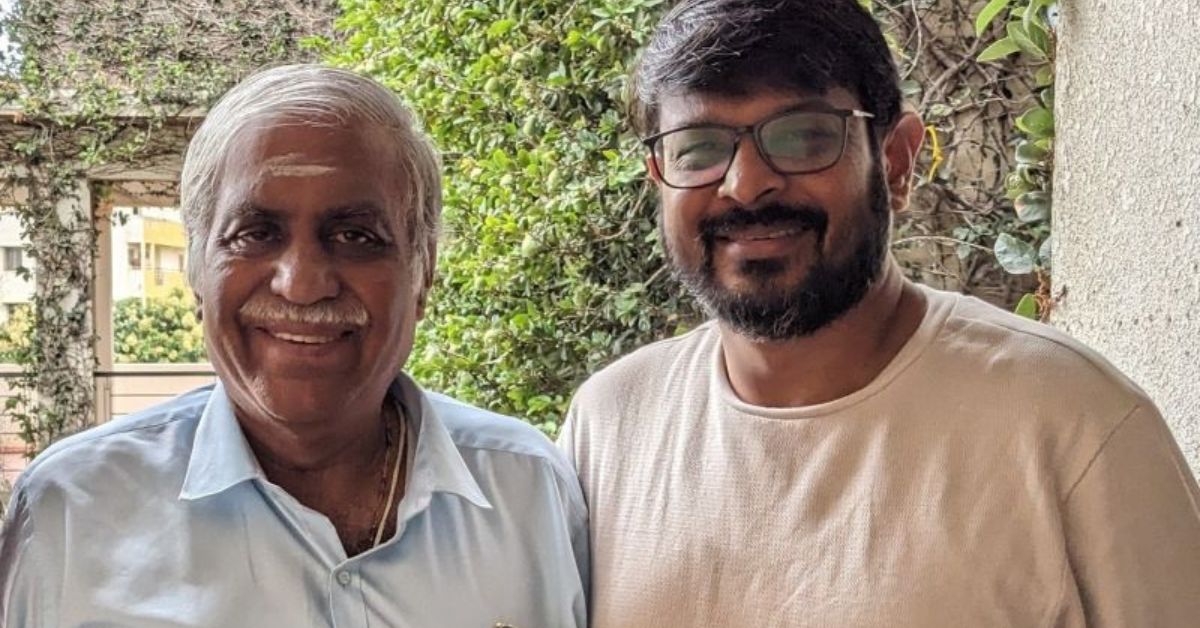

Unmoved by nature’s fury, these structures endured where many others crumbled. The credit lies in their time-tested construction techniques, says architect Rahul Bhushan, who offers a keen lens on how traditional methods continue to withstand the test of time.

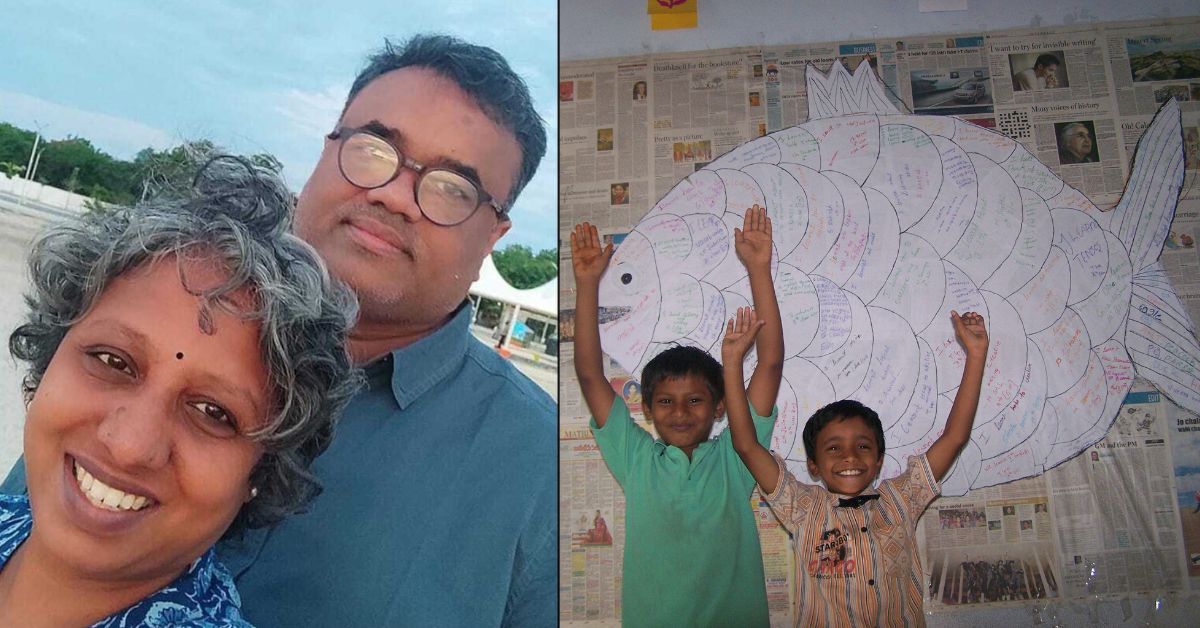

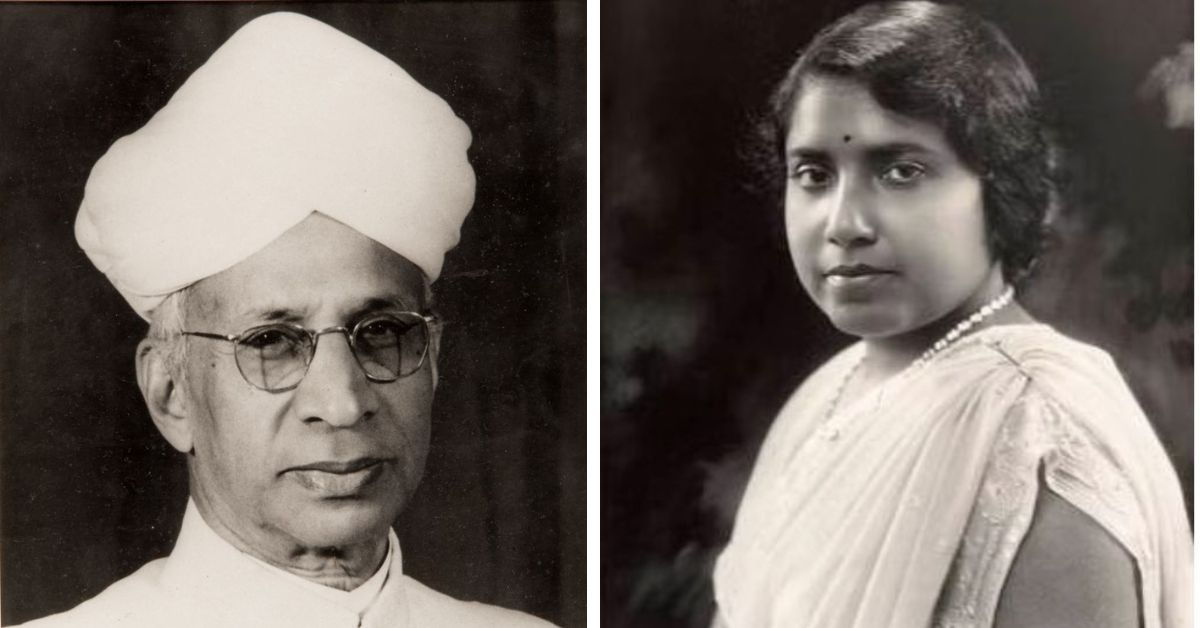

Rahul, who runs the sustainable homestay and collective ‘NORTH’ in Shimla’s Naggar, explains that the genius of these techniques emerges from the confluence of diverse cultural practices across India.

/filters:format(webp)/english-betterindia/media/media_files/2025/09/12/kath-kuni-sustainable-architecture-2025-09-12-18-58-23.jpg)

He emphasises that kath kuniand dhajji dewariare just two of many eco-friendly techniques that can be deployed to render homes strong and durable.

“I focus on understanding materials like wood, stone, and mud,” he says. “While kath kuniis typical of the higher altitudes of Chamba, the Kangra Valley sees more bamboo and mud in use. In Spiti and Lahaul, rammed earth construction is common.”

Their use converges on a single truth — the landscape benefits from having these eco-constructions. Using indigenous materials does not weigh on the landscape, he reasons.

/filters:format(webp)/english-betterindia/media/media_files/2025/09/12/kath-kuni-sustainable-architecture-1-2025-09-12-19-00-17.jpg)

His own homestay is constructed from reclaimed wood of an old kath kuni house, filled with stone and plastered with mud.

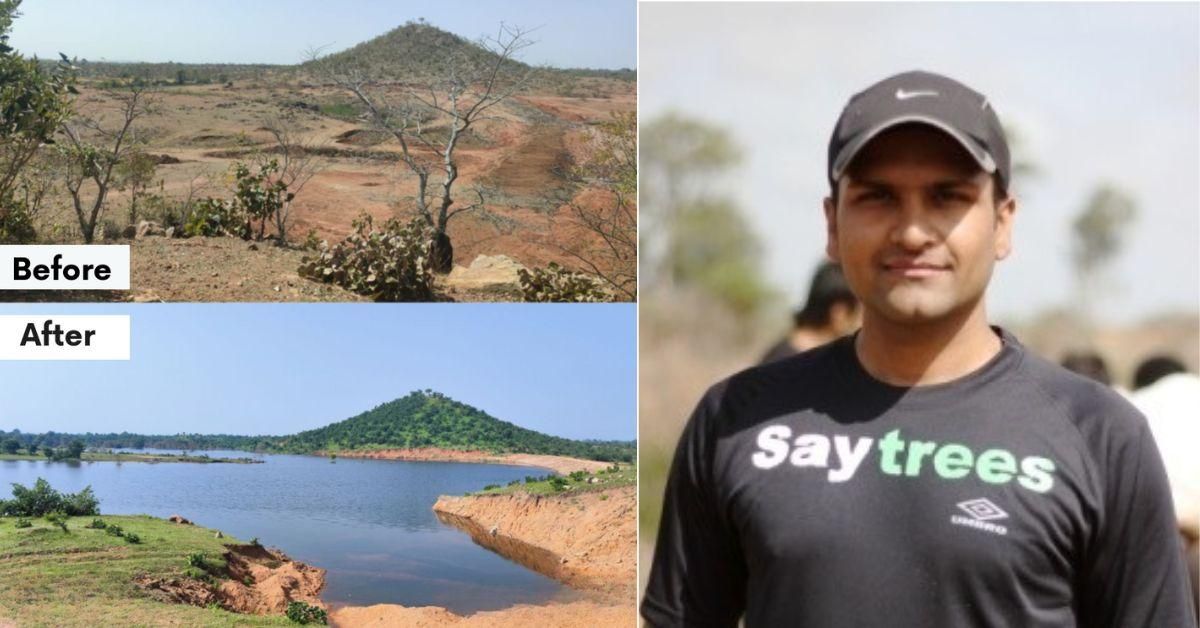

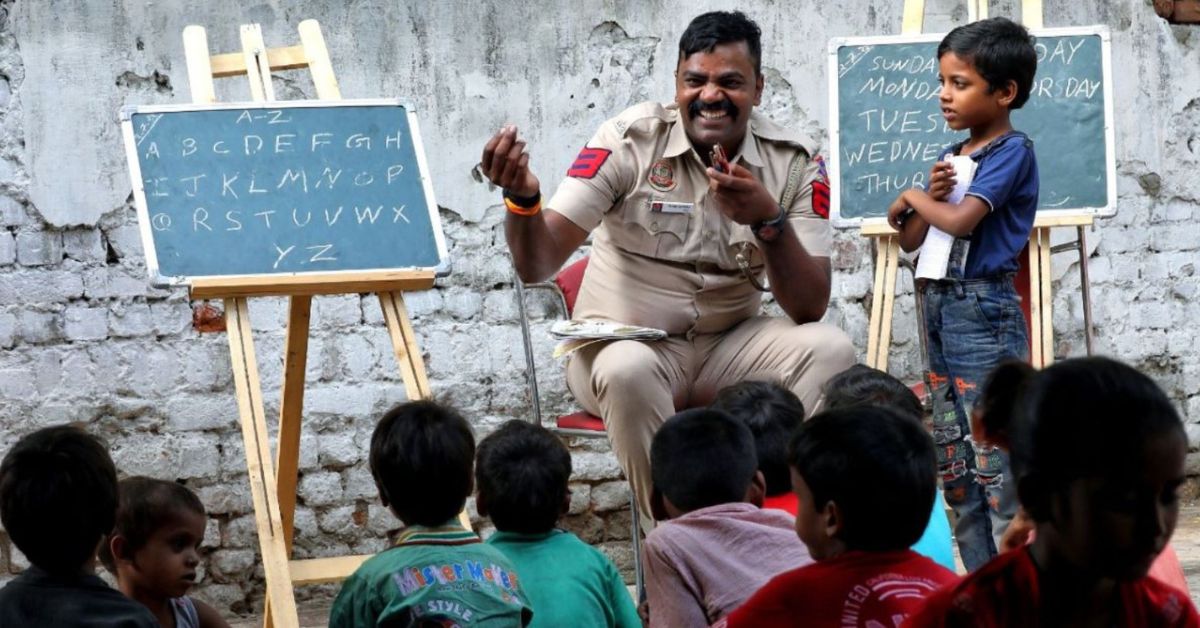

Kath kuni homes and their indomitable spirit

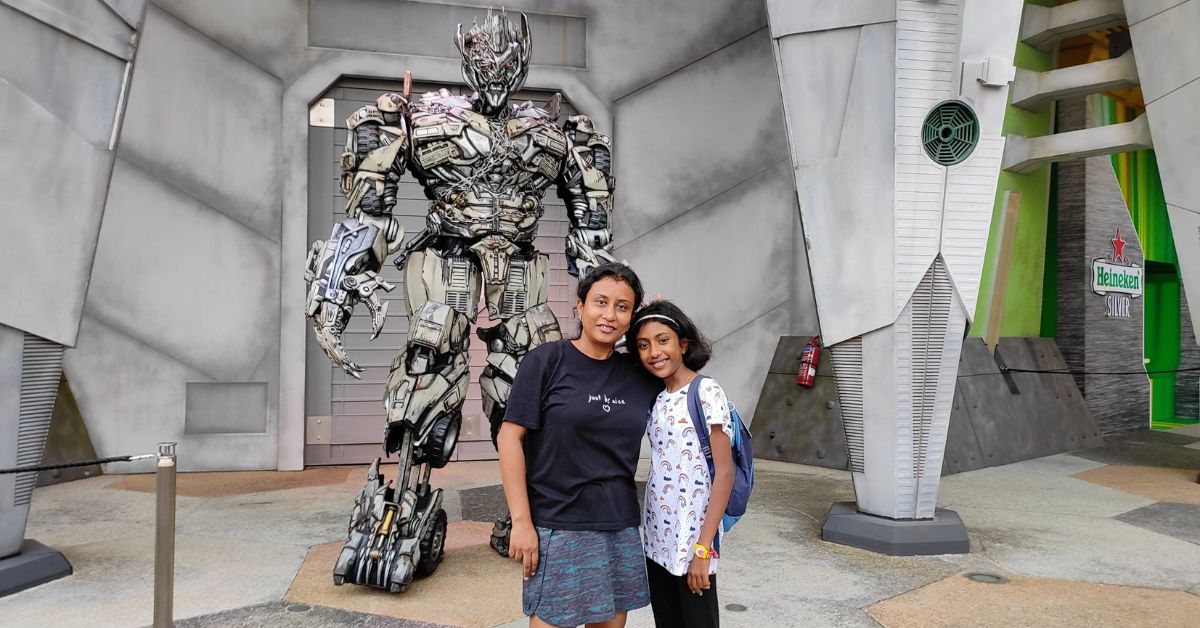

Picture an RCC (Reinforced Cement Concrete) structure; it has vertical columns. A kath kunihome, on the other hand, is hinged on horizontally layered alternative beams. That’s where the difference lies, Rahul explains.

“From a scientific and technical perspective, vertical columns aren’t as resilient to the sheer force of an earthquake. Horizontal beams, however, create a strong framework for the entire building, allowing it to absorb shocks more effectively — whether from an earthquake or any other external force.”

Studies agree.

A field study in Jana Village, Naggar (Kullu district, Himachal Pradesh) highlights the secret behindkath kuni structures — the ‘criss-cross’ bracings or dovetail joints known as maanvi, and the wooden joineries that hold everything together. The study notes that layers of stone placed between timber beams provide stability, while the wooden framework allows the structure the flexibility it needs to withstand shocks.

/filters:format(webp)/english-betterindia/media/media_files/2025/09/12/kath-kuni-sustainable-architecture-2-2025-09-12-19-02-38.jpg)

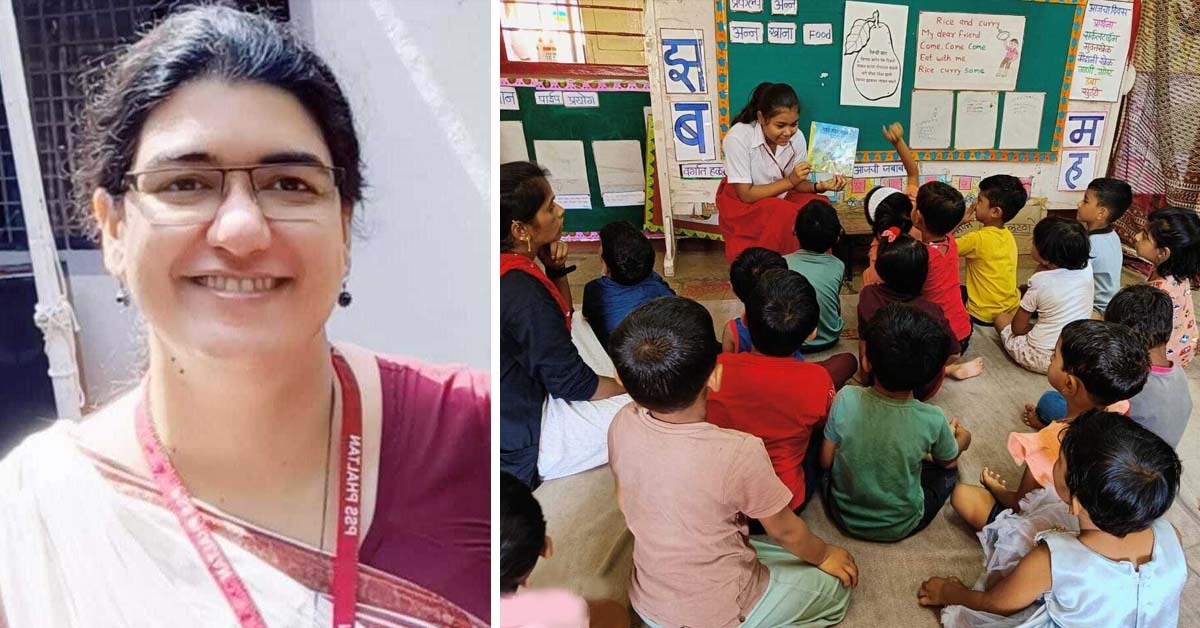

“During the earthquakes, kath kuni structures may shake and generate cracks, but there is little possibility of them collapsing entirely,” the study notes. It further adds that these spaces offer natural thermal insulation — the thick walls retain heat, while the mud plaster allows free movement of air.

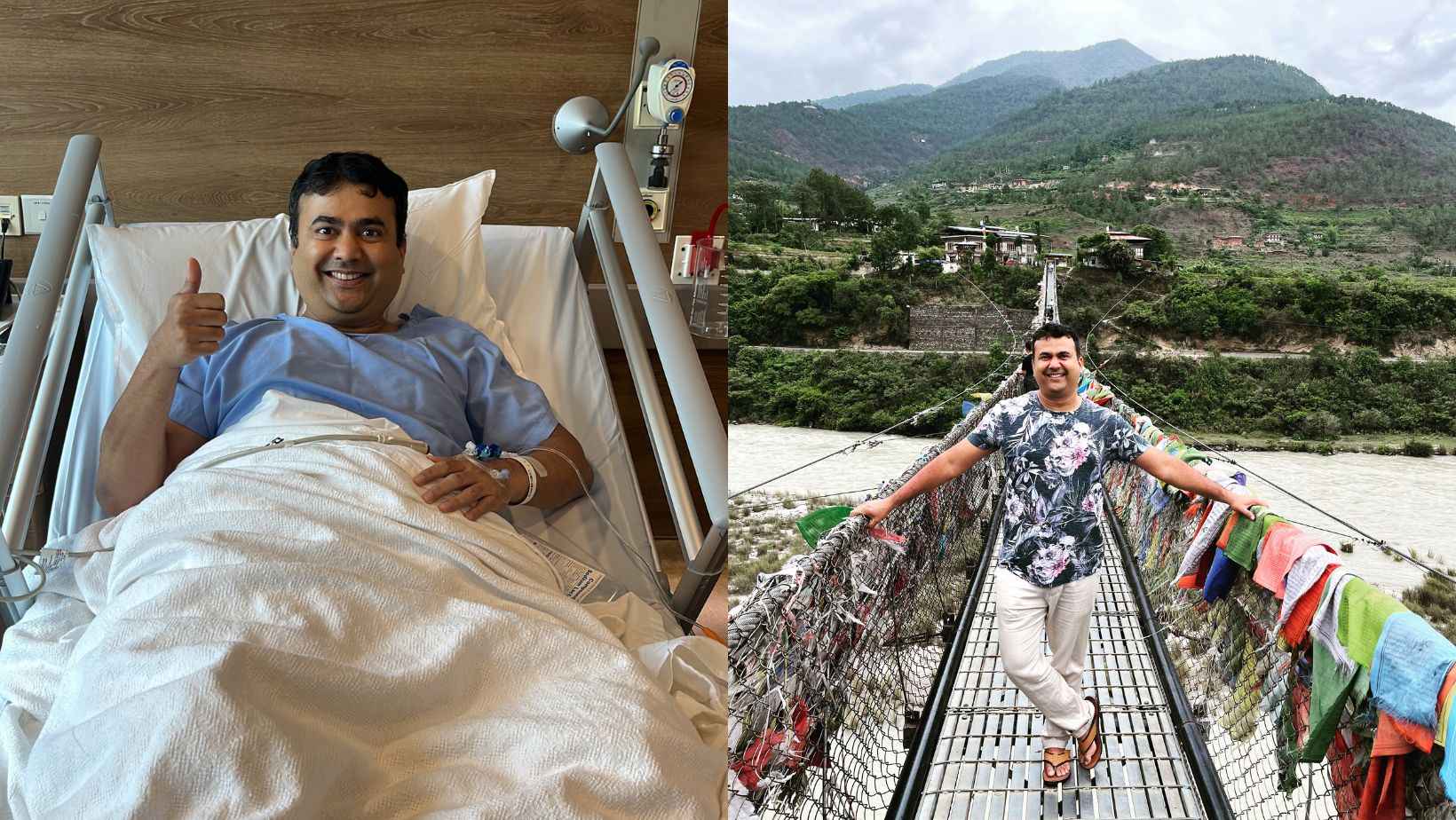

There’s another feature which makes these homes special.

The trench is dug in proportion to the structure’s height, filled with loose stone blocks that rise to form the plinth. “The elevated podium provides stability to the house while also protecting it from the snow and rainwater,” the study points out. The slanting roof — held together without nails or mortar — keeps the structure firm while its slope ensures easy drainage of rainwater.

/filters:format(webp)/english-betterindia/media/media_files/2025/09/12/kath-kuni-sustainable-architecture-3-2025-09-12-19-04-54.jpg)

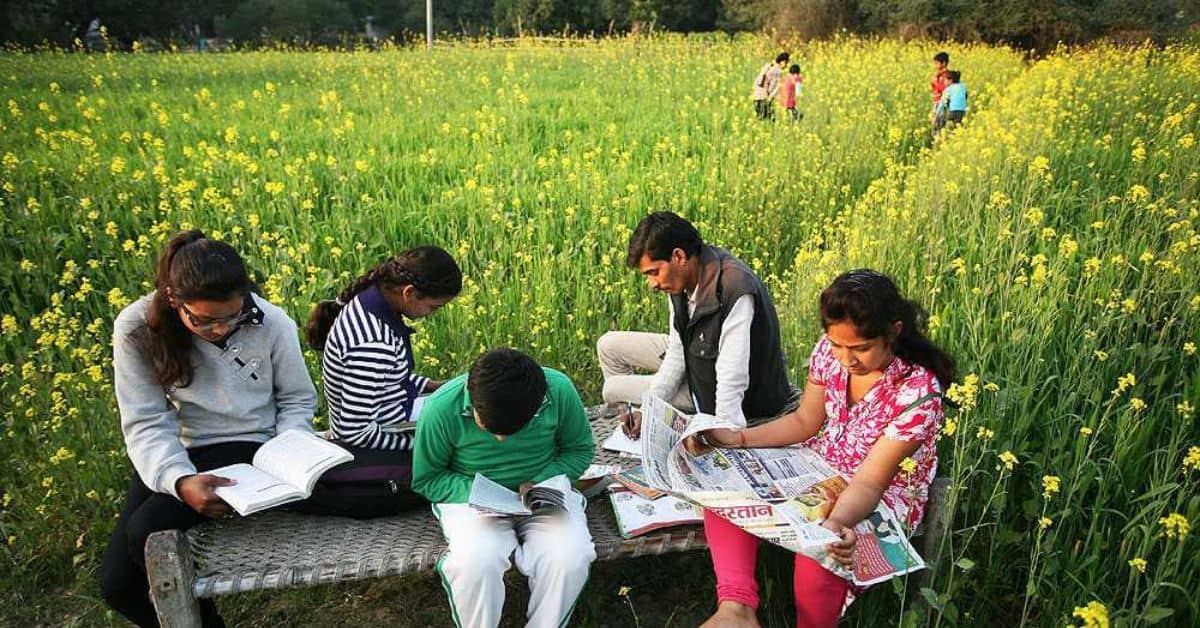

But as Rahul sees it, even beyond the architectural nuances, these building techniques are respectful of the land. “If someone builds a kath kuni house on a riverbed, problems arise because riverbeds are floodplains, with soil better suited for agriculture than for stable construction,” Rahul says.

He notes that traditional wisdom had long recognised this: old villages were never built in river basins but on the mid-slopes of mountains, where solid rock strata provided safer, more resilient ground. These indigenous technologies, he explains, took into account the local flora, soil, strata, and topography — ensuring truly sustainable settlements.

He illustrates this with an example of Kullu, where the floodplains along the river were used for growing rice and later transformed into apple orchards, not for building homes. This reflects the older generations’ awareness that while floodplain soil is fertile for crops, it is not as structurally strong as the rocky mountain terrains higher up.

As communities embrace newer forms of architecture, nature beckons us to look towards the past and learn from techniques that have stood the test of time.

Edited by Pranita Bhat; All pictures courtesy Rahul Bhushan